Why does Canada give away its best ideas in AI?

Artificial intelligence is catnip to cheque-wielding politicians. But their investments won’t pay unless we stop hawking patents

Kathleen Wynne, premier of Ontario, right, poses for a selfie photograph with a man wearing a virtual reality (VR) helmet in the Vector Institute at the MaRS Discovery District in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, on Thursday, March 30, 2017. A new institute for artificial intelligence research opened Thursday with funding from the federal and Ontario governments as well as the private sector. The Vector Institute will specialize in the fields of machine learning and deep learning, which uses software and algorithms to simulate the neural circuits of the human brain. (Cole Burston/Bloomberg/Getty Images)

Share

The opening of the Vector Institute for artificial intelligence at the end of March served as an opportunity for politicians from all levels of government to champion their commitment to jobs, technology, and most importantly, innovation. The Toronto-based facility received $100-million from the province and the federal government, plus an anticipated $80-million in private funding, to become a “world-leading centre” for AI research. “These investments strengthen our position as a global leader in the innovation economy,” Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne was quoted as saying in a news release. “By encouraging cutting-edge technology like AI,” federal Finance Minister Bill Morneau enthused, “we will be with Canadians every step of the way as they lead us into a future filled with possibility.”

The Vector Institute is indeed a legitimate achievement, even scoring a bonafide AI superstar to serve as its chief scientific advisor: Geoffrey Hinton, a deep learning pioneer, University of Toronto professor and an engineering fellow at Google’s machine-learning project. It’s fair to assume the Vector Institute will help draw AI talent to Canada, and startups will emerge as a result. The federal government is investing heavily in the field, too, having allotted $125-million in the most recent budget for the Pan-Canadian Artificial Intelligence Strategy.

But Canada’s dream of building a world-beating AI sector will remain exactly that—even with the Vector Institute—unless policymakers can figure out how to stop the leakage of intellectual property out of the country. “We’re locking ourselves out of the possibility of creating an AI powerhouse in Canada,” says Richard Gold, a law professor at McGill University and the founding director of the Centre for Intellectual Property Policy.

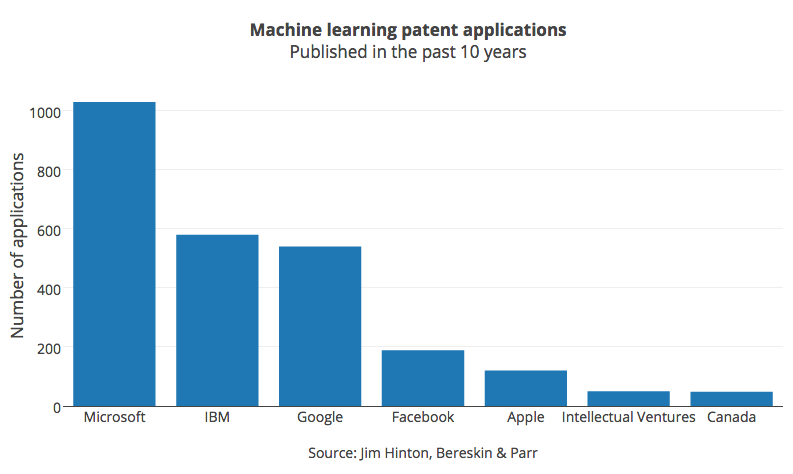

One of the crucial measures of success for the Vector Institute will be the fate of any patents developed by researchers: will the intellectual property ultimately remain in Canada, or be sold to a foreign tech giant (it should be noted that Google, one of the biggest acquirers of AI patents, contributed to $5-million to the Vector Institute). The track record in Canada so far is not promising. Out of the 100 or so patents related to machine learning that have been developed in Canada over the past 10 years, more than half have ended up in the hands of foreign companies such as Microsoft and IBM, according to research from Jim Hinton, an intellectual property lawyer at Bereskin & Parr in Waterloo, Ont. (no relation to Geoffrey Hinton).

Canadian researchers were in fact trailblazers in AI, and it’s only now that policymakers are governments are scrambling to make up for lost time. “We’re waking up after our crown jewels have been stolen,” says Dan Breznitz, the chair of innovation studies at the Munk School of Global Affairs. That makes it especially difficult for Canadian tech companies to grow beyond the startup phase. Large tech firms with vast patent portfolios, such as Google and Microsoft, fiercely protect and enforce intellectual property rights, and try to extract hefty licensing fees from fledgling Canadian startups—or simply take them to court. Faced with those options, it’s no wonder many Canadian entrepreneurs end up selling their firms and transferring whatever IP they do have.

That puts Canada in a situation where governments subsidize research, only for foreign companies to snatch up IP on the cheap. Those same firms can then charge licensing fees to Canadian companies, in addition to using these patents to develop products and services to sell back to Canadians. “If we just gave away the money on a street, we’d basically do as well,” Gold says.

Addressing the problem requires more than just ensuring that Canadian entities retain ownership of IP. “Google Canada can be just as vicious to Canadian entrepreneurs as Google in the U.S.,” Breznitz says. Rather, the key issue is how publicly funded IP is used. “All those patents that are developed with taxpayers’ money should be available for Canadian entrepreneurs to use at a nominal cost basis,” Breznitz says. Research institutes and small-and medium-sized businesses could pool IP, and license those patents to other Canadian startups at cost. That would allow startups to continue growing and not clash with foreign competitors charging egregious licensing fees or threatening legal action.

A more formal approach is to create a sovereign patent fund—a government-backed entity that would manage and monetize IP, and provide protection to Canadian startups that find themselves in the crosshairs of litigious foreign multinationals. Jim Balsillie, the former co-CEO of BlackBerry, has been touting this idea for the past few years. Research from the Centre for Digital Entrepreneurship and Economic Performance in Waterloo (and co-authored by Hinton at Bereskin & Parr) has also shown sovereign patent funds to be effective in other countries, such as Japan, South Korea and Taiwan.

Governments seem to be aware of the problem, at least. The federal Liberals made a half-hearted nod to the IP issue in the budget, vowing to “develop a new intellectual property strategy over the coming year” (No further details were provided). The Ontario government is pledging to work with the feds on its Canada-wide IP game-plan, and a spokesperson told Maclean’s that the terms of the province’s agreement with the Vector Institute require it to “apply a ‘Canada first’ and ‘Ontario first’ lens when making decisions about commercialization of its intellectual property.” The Vector Institute, meanwhile, is currently developing its IP policy, according to a spokesperson.

These statements, though vague, are somewhat promising, according to Gold. “Until there is more detail, it is hard to evaluate,” he says. But it’s important that policymakers get the details right. If the country squandered its AI potential once before, it certainly can’t afford to do it again.