Quebec’s seriously odd, strangely important election

Paul Wells: Even the most staunchly federalist or sovereignist observers have, over the years, yearned for a normal Quebec election. And then they almost got one.

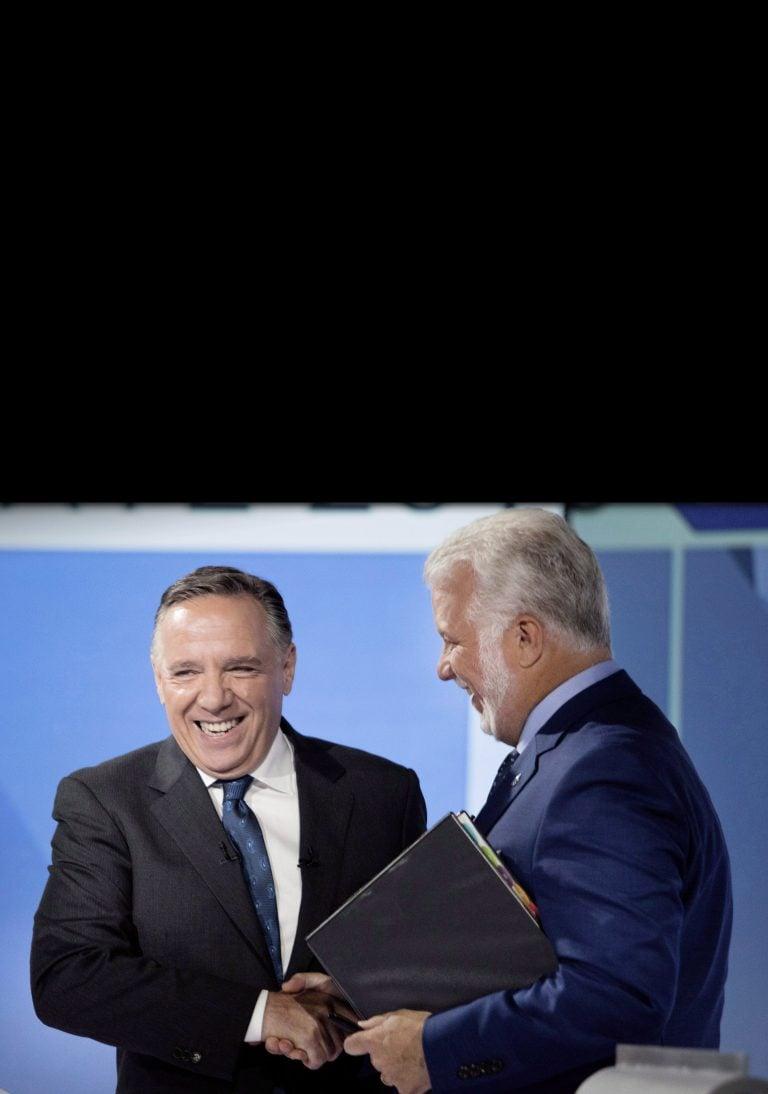

CAQ leader Francois Legault, left, shakes hands with Liberal Leader Philippe Couillard after their English language debate, Monday, September 17, 2018 in Montreal, Que. (Allan McInnis/CP)

Share

I think like a lot of observers I’ve been waiting for the polls to settle before I decide what the current Quebec election campaign is about. Well, the vote’s on Monday and there’s little hope of the polls settling.

The numbers haven’t been wildly fluctuating, but they represent an equation in four variables and it’s impossible to have any real confidence in the outcome. The poll aggregator Qc125.com puts Philippe Couillard’s Liberals a hair ahead of the upstart, never-been-in-power Coalition Avenir Québec (CAQ), led by François Legault. The Parti Québécois is near (actually, has been consistently below) their worst-ever popular-vote score, the 23% posted by René Lévesque when he first led the new party into a general election in 1970.

READ MORE: Quebec election 2018: Live results map

PQ leader Jean-François Lisée has ended the campaign in a bitter dispute with Manon Massé, who leads (well, co-leads) (well, co-speaks for; it’s complicated) the lefty-left Montreal party Québec Solidaire. QS is on track to at least double their previous best score of 7.63% of the popular vote. It’s not crazy to think they could triple that result. Their voter base is overwhelmingly young voters heading into the first or second voting booth they’ll ever have seen. The more QS rises in the polls, the more trouble Lisée’s PQ is in. It must be maddening: Lisée has at times fought for a more left-leaning PQ, one that keeps its ties to artists and the creative class, and he’s been fighting for the biggest possible sovereignist tent for almost 25 years. And now these guys come along and help seal his party’s debacle. God is an iron, as Spider Robinson wrote.

But beyond the likely or possible outcomes, this has been a fascinating campaign in a bunch of ways. I wanted to share a few observations in the home stretch.

First, Philippe Couillard. It’s a time of heightened concern over immigration and border-crossing in Quebec, due largely to the thousands of people who’ve walked across the border from the United States into Quebec in the last two years. The federal Conservatives have stepped up their rhetoric over border crossing. Maxime Bernier shuffled the issue from 10th to, arguably, first in his deck of personal preoccupations, on his way to forming a new party. It’s pretty popular to regard borders, migrants and immigrants as the demagogue’s issue set of choice this season.

But Couillard is having none of it. During the middle of the campaign, when he plainly had Legault on the run for a bit, the premier used Legault’s own immigration policy as a weapon against him.

The CAQ wants to “temporarily” reduce the number of immigrants accepted in Quebec every year from 50,000-plus to 40,000. He’d make newcomers take French tests and seek to have anyone who fails a French test within three years leave the country, or at least the province. How he’d do it, or what the threshold for such a decision would be, are hard to tell. He hasn’t been good at explaining. This whole set of CAQ policies raises a lot of questions. But Legault plainly thought its vagueness was a bonus, not a problem — until Couillard chased him around the province poking holes in his immigration plan for days on end.

The polls suggest Legault has recovered in the home stretch, and if he isn’t the premier after Monday, it’ll be a surprise. But I want to step away from the poll narrative for a minute and underline the fact that an embattled incumbent Liberal premier, running from behind in a province whose nerves have been frayed by constant stories about border crossers, decided to run against cutting immigration levels. This is, it seems to me, almost a heroic choice. He must surely have received advice not to choose this stance. If he did, he’s ignored it.

Couillard, a brain surgeon by training (no, really), is a cool cucumber, bad at conveying strong emotion, and he spent most of the campaign depicting his relatively pro-immigration stance as simple common sense: employers face a shortage of workers, the domestic workforce can’t fill all the jobs that have gone wanting, so why wouldn’t Quebec continue reaching beyond its borders for workers? But in the home stretch, he’s allowed himself to get more emotive. In a Liberal ad stitched together from Couillard campaign speeches, he says: “No to expulsion. No to tests. No to discrimination. All Quebecers united!”

The Quebec economy is doing well. Why’s Couillard in such trouble? Fatigue is the usual answer, after 15 years of almost uninterrupted Liberal reign. Bitter memories from the sharp cuts he instituted in 2014 and 2015 to get Quebec back onto a sustainable fiscal track. I’d add Couillard’s own limited communications skills: He’s a superb talker with a fearsome command of detail, but that’s not the same as being able to tell a story or bring a crowd along with you. Still, if he loses on Monday, I suspect he’ll look better in hindsight to many voters than he looks today.

His likely successor, François Legault, is approximate, like a waiter who brings you beer after you order Coke, then apologizes and returns with a basket of bread sticks. He got rich in discount air travel before joining the Parti Québécois in 1998. Seen as a star and a potential future leader for the sovereignist party, he served as minister of this and that until Bernard Landry lost to Jean Charest in 2003. He stayed on in opposition until 2008. In 2011 he helped found this new party, whose centre of gravity is centre-right and whose main distinguishing feature is that it is neither federalist nor sovereignist, nor even particularly interested in the question.

Every election, as a student of Quebec politics living outside Quebec, I get asked whether the likely next premier is somebody to be scared of. I have been saying “No” since Lucien Bouchard retired, and I’m pretty sure it’ll be no if it’s Legault. This disappoints my interlocutors, who like to be frightened by Quebec politics, but I’m stuck with the facts.

But isn’t Legault a separatist in disguise, I’m asked? No, I think it’s likelier that he disguised himself as a separatist to get a cabinet post in Bouchard’s government. Or that he was about as sovereignist as Justin Trudeau is Roman Catholic: he knows the catechism but is not often spotted in the movement’s usual places of worship. Legault never talks about Canada. He may not believe it exists. I wonder whether he’s been to Halifax or Edmonton. I wouldn’t bet money on Toronto. At premiers’ conferences, he’ll be the one checking his watch every several minutes and blanking on Brian Pallister’s name.

But isn’t he a xenophobe? That one will depend on your definitions, I suppose, but I’m almost sure that if he thought promising more immigration was a winning proposition, Legault would stand at the Lacolle border crossing wearing a BIENVENUE!/WELCOME! sandwich board, handing out Twizzlers. The CAQ’s 2018 campaign slogan is the fabulously meaningless “Maintenant” (“Now”), but it might as well be “Whatever You Want, Voters.”

A distant spur to the CAQ’s creation was a 2005 manifesto called Pour un Québec lucide (roughly, “For a Clear-Eyed Quebec”), written by Bouchard with several other prominent intellectuals. Its basic argument was that Quebec had to make tough choices. Higher university tuition, higher hydro rates, steady immigration, all with an eye to beefing up provincial revenues and maintaining a robust workforce. The sovereignty debate was essentially a distraction from that hard thinking, the document said.

Essentially none of the Lucide philosophy survives in the CAQ, except agnosticism on the sovereignty issue. Certainly the eat-your-vegetables asceticism favoured by Bouchard and his associates is long gone. Whatever Legault’s real-life immigration policy in government turns out to be, it’s a safe bet it’ll change on a dime if it gets three nights of critical coverage on TV. Legault will not ever be an inspiring premier, but neither will he be a bullheaded ideologue ramming through some incomprehensible reform for the sake of philosophical purity.

The last of the main party leaders is Jean-François Lisée. He’s been a fascinating leader for the beleaguered PQ. He will be lucky to avoid a historic debacle on Monday. The surprise is that he’s been enjoying himself so much.

Lisée was one of the finest political journalists of his generation when he showed up at Jacques Parizeau’s first news conference after Parizeau won the 1994 election. The surprise – more than a surprise, it was shocking – was that Lisée walked in the room with Parizeau, as an advisor. He was a key strategist in the near-victory of the 1995 referendum, stuck around to counsel Bouchard, has been a leading sovereignist thinker through the 15 years since then.

On the night Couillard was elected in 2014, I wrote that the PQ was wedded to policies most Quebecers rejected, but that it was so firmly wedded to them that it would be hard to walk away from them. Lisée surprised everyone by getting his party to make a huge concession on sovereignty: it would promise not to hold a referendum on secession during its first term in government, under any circumstances. The surprise is not merely that Lisée decided that barge-pole distance between the party and its raison d’être was necessary, but that he got the party to agree.

Lisée has stuck to that vow. And his party has, for a year, been stuck at levels of support well below its catastrophic 2014 showing. Perhaps the no-referendums promise has demoralized PQ lifers or even given them moral license to shop their support around to other parties. All we know for sure is that it hasn’t helped.

The surprise, though, is the immense pleasure Lisée takes in campaigning, even if the outcome is likely to be painful. His campaign bus looks like an LSD trip. His slogan is “Sérieusement,” seriously, and it’s meant to be intoned with all the sarcasm and eye-rolling the word implies. Because Lisée understands what a joke his party had become by the time the campaign began, and he’s decided to just… go with that.

On the stump, Lisée improvises long speeches full of ribald jokes, wordplay, references to literature and song, and a wickedly accurate impression of François Legault’s folksy drawl. But neither is he free-associating: He makes the policy and tactical points he came to make, fires up the base, leaves the newspapers writing the headlines he wanted them to write.

The parallels to the festive, colourful Oui campaign in the 1995 referendum are obvious and, I’m sure, not accidental. Lisée helped conceive that campaign as well as this one. It worked better that time than it has this time. But Lisée has not flagged, is — apart from a badly-chosen attack on Québec Solidaire leader Manon Massé in the last of three debates — not giving in to bitterness or panic. It’s as though he sat himself down several weeks ago and said, “It is what it is. But I will never get another chance to run a campaign as the leader of this great party. So I’m going to do it my way.” And amid the constant plodding wariness of so many other party leaders in so many places, it’s been a pleasure to watch.

Even the most staunchly federalist or sovereignist observers of Quebec politics have, over the years, yearned for a normal election, one that would turn on some other issue — prosperity, broader values, social justice. No Quebec election at least since 1985 has managed to deliver on that dream as thoroughly as this one. And as we should have expected would be the case with an election that stands as a departure from grand schemes and cliff’s-edge crises, this one has been a little mundane and frazzled. But in contrast with many of those grander confrontations, it has also been oddly heartening.