The death of the Alberta PC dynasty

It didn’t happen overnight. Inside the unravelling of the longest-serving provincial regime in the history of Confederation

Alberta Premier and Progressive Conservative party leader Jim Prentice reacts after losing and leaves the stage after the Alberta election in Calgary, Alberta, May 5, 2015. Todd Korol/Reuters

Share

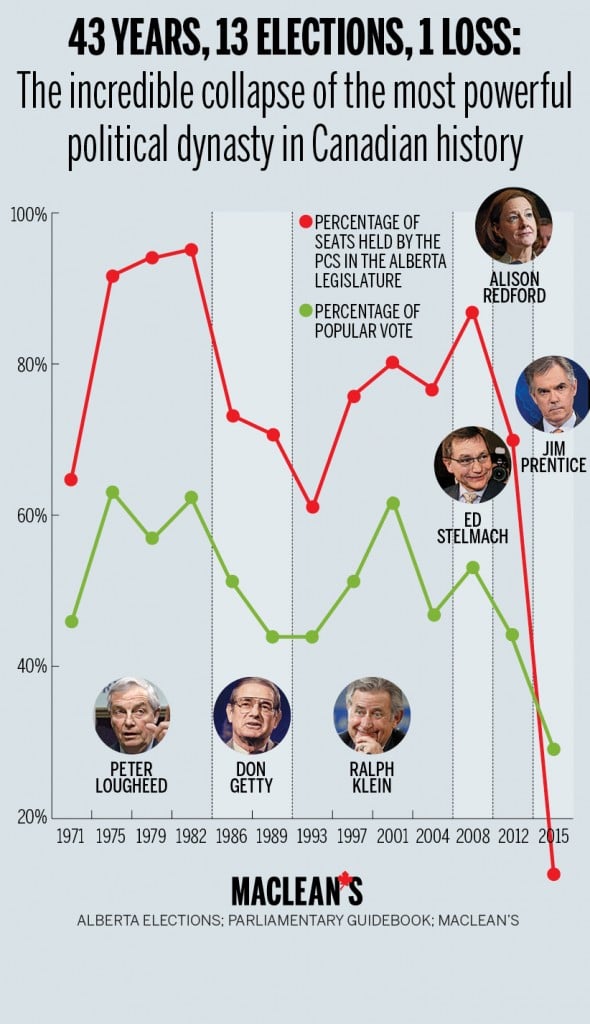

They have lost the Mandate of Heaven. Alberta’s Progressive Conservative Party, winners of 12 consecutive elections, holders of power for almost 44 consecutive years, longest-serving provincial regime since Confederation, has been blown out. Humiliated. Dethroned and decapitated. The New Democratic Party, long deemed pathologically intolerable to Alberta voters outside Edmonton, stormed to a large majority in Tuesday’s election. The Wildrose party, whose leaders and major figures were grovelling before the PC juggernaut mere months ago, lapped the PCs to become the official Opposition.

Until hours before the polls closed, there was universal doubt such a thing was possible, and there were many professional predictions of yet another PC majority. The anger at the Conservative establishment in the province was undisguised. Right-wingers were disillusioned; those on the left were scalded by generations of disappointment. Many people who intended to vote for Rachel Notley’s NDP—the PCs got hammered even amongst seniors who had turned out for them for most of a lifetime—were not sure their neighbours felt the same way. The province had the feeling of a conspiracy on the eve of a coup. Would the tanks show up? Would the stormtroopers capture the radio stations on schedule?

All went, for once, exactly as the pollsters had insisted it would. The PCs lost ridings they had won in 2012 by 5,000, 6,000 votes. Jim Prentice, the man of connections and charm called upon to save the chaotic Conservatives from themselves, now bears responsibility for steering a magnificent political machine into the ditch. It’s not all his fault. This is one of those overnight sensations that did not happen overnight.

It is probably facile and cheap to say that the Tories’ troubles really began when Ralph Klein left politics in 2006. Facile, cheap, and . . . in an obvious sense, true. In that year, Ed Stelmach won a three-sided fight for the succession by being the moderate alternative to two front-runners, Jim Dinning and Ted Morton, that large blocs in the Progressive Conservative party could not swallow. Dinning had been a much-praised minister of finance and education. Morton was a swashbuckling ultra-conservative intellectual who later proved pragmatic enough in office to gently push the merits of a sales tax in Alberta.

The party infighting would chase Dinning out of politics at once, as he retreated to the world of business, and its effects ultimately did in a demotivated Morton in the election of 2012. It’s a theme amongst the Conservatives in the last decade: every loyal Tory has a list of alternate-reality premiers who would have changed everything. (Dinning, in particular, appears on a lot of them.)

Stelmach’s premiership would run aground on a poorly timed attempt to hike oil and gas royalties without much buy-in from the industry. As a leadership candidate, Stelmach had floated a series of big ideas—Quebec-style provincial control of immigration, an Alberta Pension Plan—that no one really expected him to implement or even follow up. He turned out to be as serious as a shotgun, though, about the royalty thing.

That impulse led to a sequence of disasters. One of the royalty review’s nominal authors, an economist, put her name to a private analyst firm’s report attacking the whole thing within days of supposedly finishing up work on it. Lyle Oberg, the finance minister to whom the report was directed, left cabinet weeks later, displaying undisguised annoyance with Stelmach. Like other senior Conservatives from the Klein era, he would eventually endorse the Wildrose party while Stelmach was still in the premier’s office.

Related: Paul Wells: How Rachel Notley took spectacular advantage of a moment

The report was implemented, and government royalty revenues promptly fell 43 per cent in a single year, compounded by a dip in world prices. Stelmach had to pull back on the changes even as his overall fiscal plan fell to pieces. Alberta has only now struggled back into a technical surplus position, with the emphasis on “technical.”

When Stelmach “solved” the political problem by retreating, he stuck the PCs with the worst of both worlds. There had been—there is now—a real desire for a serious, informed review of whether Alberta was capturing oil and gas rents efficiently. Moreover, concerns over rent extraction are mixed up in the public mind with environmental suspicions and fears that the province is not saving enough of the revenue. Stelmach had jabbed at all these buttons like a spoiled kid in an elevator, then departed with nothing accomplished.

His premiership cost the Conservatives a core component of their reputation: the appearance of secure managerial competence. For all that Ralph Klein is still remembered for blowing up hospitals and arguing with homeless people, his regime was a time of progress and tight labour markets for the median Alberta worker, rapid modernization in the province’s economy, and growing government revenues that outpaced spending. After the semi-articulate Stelmach, the Alberta public was ready for a 21st-century Progressive Conservative leader. Enter Alison Redford—ultra-connected Calgary lawyer, jet-setting international aid organizer and adviser, and probably the most eloquent of Alberta’s post-Klein premiers.

Redford did for the PCs’ ethical reputation what Stelmach had done to its managerial bona fides. This was not all her fault, although as faults go, trying to build a customized premier’s residence in the heart of the capital without telling anybody looms very large. But Redford’s downfall, and the harm done to the Conservative brand as a consequence, came partly because of an intensifying culture of political transparency that she had embraced. (She just wasn’t very ready to live in it.)

She was undone partly because of expense reports that the government started publishing at her insistence. She also imported the Ontario idea of a “sunshine list” of top government salaries. Merwan Saher, the no-nonsense auditor general who defied Alberta habit by actually making use of his political independence when Redford’s wastefulness and deception involving government planes began to emerge, had been a Stelmach appointee. Elections Alberta, despite some political and legal controversies, did important work in investigating and documenting the web of illegal kickbacks from schools, municipalities, and other provincial institutions that the Progressive Conservatives had come to take for granted in hinterland Alberta.

Political financing disclosures added to this picture, showing that the PCs have consistently relied on donations from corporate clients of government—contractors, builders, professional associations—that would make heads rotate and/or explode almost anywhere else in the continent. The documents are online for all to see, and are faithfully updated every quarter.

Senior Conservatives who abandoned Ed Stelmach tended to do so reluctantly. Redford, who came to the premiership without caucus support and led the party in a paranoid, abusive style, positively drove them away. By the time the constituency associations rose up against her in 2014, as colleagues in the legislature visibly cheered on the rebellion, the Tories were beginning to be perceived not only as bunglers, but crooked bunglers.

Yet Stelmach and Redford both won massive majorities at Alberta elections. Both sought the approval of the electorate early in their terms, before their respective flaws had begun to devour them. There were subtle signs of weakness, visible but never clear enough to impose themselves overwhelmingly on the observer.

Voter turnout was 45 per cent for Ralph Klein’s perfunctory final election in 2004. It would seem almost impossible for it to go lower, but for Ed Stelmach’s 2008 win, a feeble 41 per cent of eligible voters straggled through polling stations. That suggests voter indifference between the alternatives—not necessarily a bad thing, but an indicator of danger for a governing party if the opposition were ever to get its act together.

In the 2012 election, perceived in the final days to be closely contested between the Wildrose party and the PCs, turnout rebounded to 54 per cent. At that point Redford still seemed like a breath of fresh air. Having a fund of goodwill to work with—a hard thing to believe in 2015, when she has practically become an exile—she dealt successfully with scandals like the legislature’s “no-meet” privileges committee, which paid MLAs a soupçon of extra salary without ever actually convening. The Conservatives, struggling in the polls halfway through the campaign, tore up their cruise-control plan and went negative against the Wildrose, successfully portraying its future caucus as a potential gang of gay-bashing, social-conservative savages.

It saved the day for the PCs, but Stelmach’s 53 per cent share of the province-wide vote had dropped to 44 per cent. And the Navigator Ltd. braintrust that swept in to teach the Conservatives the facts of political life has now become a further source of scandal for the PCs, having received hundreds of thousands of dollars for sole-source contracts to perform “emergency” communications work after the Alberta spring floods of 2013. Not only did senior Alberta civil servants (working for a grateful Redford) violate rules about sole sourcing, but a $240,000 Navigator contract was almost totally undocumented, and other contracts were much more expensive than usual.

In retrospect, the sense one has of the last decade in Alberta politics is of a governing party getting closer and closer to the end of its rope. Klein concluded his career with a few years of relative lassitude, possibly already feeling the effects of the respiratory illness and dementia that would combine to end his life. Stelmach arrived with a new vision, but his first step was on a land mine, and it left him and his successor with little fiscal wiggle room for ambitious, transformative moves. The party disposed of him and appeared to renovate from within, as it had done so often. It won another election by stampeding the voters with terror and, implicitly, appealing to the comforting familiarity of PC government. An oil-price collapse followed a global recession. Scandals once tolerated serenely began to pullulate in an age of social media. Another inconvenient leader was disposed of. Enter Jim Prentice.

What kind of province was Prentice being asked to retrieve for the Progressive Conservative cause? It is a environment of fast demographic change. Just from 2008, the year of Ed Stelmach’s win, to 2014, Alberta gained about 430,000 citizens—a net increase of 15 per cent. The university-educated segment of the population grew fast: that is usually good news for left-wing parties, and the 2015 election polls suggest they have now gone heavily NDP. The union-influenced health professions have also grown 50 per cent since 2008.

Despite facts like this, Prentice deliberately chose the New Democrats as his main strategic opponent by calling an early election when no other opposition party had a permanent leader in place. The bizarre, late 2014 migration of 11 Wildrose MLAs to his banner, including leader Danielle Smith, seemed to have eliminated his right-wing rival. And Prentice sent early signals that he might run quite a hard-right Alberta government. But the Wildrose quickly found its own new leader from a background in federal politics, Fort McMurray businessman Brian Jean, and the mass floor-crossing somehow began to seem more like an exercise of unseemly influence by Prentice than an unforced error by enemies.

The Alberta NDP, having almost no other option, has run a campaign based on a tweaked version of Prentice’s budget plan, one that gets back into surplus slightly slower and introduces even more progressivity to the tax structure. The NDP platform is deliberately short on utopian social vision. Leader Rachel Notley has said generic positive things about the oil industry while pushing a second royalty review. She and federal NDP Leader Thomas Mulcair maintained a respectful mutual distance. The media, frozen by uncertainty about the outcome, has been slow to analyze the possible makeup of a large NDP caucus nobody foresaw.

Past Conservative election efforts have depended heavily on the fact that hundreds of thousands of older Albertans are refugees, or the children of refugees, from NDP-run provinces, particularly neighbouring Saskatchewan. Abhorrence of socialism, or just first-hand experience of its effects, have worked with the Liberal legacy of the National Energy Program for decades to keep the brands of the left divided, disliked and down.

But those folk memories are fading. Alberta’s median age is near its expected peak, and the province is thus experiencing the transition from Baby Boomer dominance to the demographic bulge in under-40s—people who do not remember cruise missiles and disarmament, stagflation, Pierre Trudeau, even classic-model Bob Rae or the free trade fight of 1988.

For Generation Y, the New Democrats are just socially and environmentally concerned people who deserve a fair shake. And those are electors now reaching the age at which there is actually some probability that they will make it out to the polls. They have already played an enormous role in the sweeping electoral victories of Calgary Mayor Naheed Nenshi and Edmonton’s Don Iveson. It’s not just a numerical role, either. Nenshi and Iveson benefit from having younger advisers who speak the language of social media and know how to communicate with a generation that fancies itself post-ideological.

Prentice’s first problem on being summoned from the private sector to be Alberta’s saviour was thus pretty simple: he is an older white male whose personal narrative of heroic emergence from a coal mine is out of sync with the spirit of the age. But he was not slow to compound that initial disadvantage.

One of the weird funhouse aspects of the 2015 election has been the way Prentice came to be seen by voters, almost Ignatieff-fashion, as somebody who had “come back” to Alberta from outside. Since Prentice left federal politics for the CIBC and other strategic troubleshooting jobs 4½ years ago, he has not really been much different from any other downtown Calgary power broker. He is basically the sort of person Alberta has always picked to be premier. (No one much mentions the close mentor-protege relationship he once had with Alison Redford.)

Related: Paul Wells reports from Alberta

But the white-knight narrative surrounding Prentice appears to have worked against him: it raised expectations unreasonably high at the outset of an oil-price crash, and any sign he gave of being out of touch was bound to be magnified. He gave himself a lot of extra opportunities for a slip-up by being remarkably diligent about press and broadcast appearances. Eventually he made his “In terms of who is responsible [for debt] we all need only look in the mirror” gaffe on the radio.

He never quite apologized for that comment, and certainly didn’t try to explain that ordinary Albertans have no responsibility for the way the public treasury has been managed. How could he? Albertans are responsible! They kept on voting for big-spending, deficit-running PC governments right through the days of hundred-dollar oil! But that was an argument Prentice didn’t want to make, even as he played the hyper-ethical super-patriarch. He was willing to hint that his immediate predecessors had made mistakes, but unwilling to run flat-out against them.

This timidity extended to a general failure, or inability, to purge the party of the elements that had attracted negative public notice in the past. To give a specific example: why, exactly, is Kelley Charlebois still appearing in Alberta newspapers? Charlebois is a Klein-era fixer whose influence in the PC party has been thorough and large for a long term. In 2004 he landed then-health minister Gary Mar in trouble after quitting as his executive assistant, returning to his employ as a consultant, and billing the ministry $389,000 over three years for largely undocumented “oral advice” on one in an endless series of PC reorganizations of the hospital system. (That was the one where they reduced the number of regional authorities from 17 to nine, if you happen to have been keeping score.)

Charlebois had to quit; an undeterred Mar would run for the PC leadership against Redford and fail, partly because of the lingering pique over Charlebois’s consulting deal. (Despite this, Mar is another person who still appears on some “alternate PC premiers we never had” lists.) Mar would become Alberta’s agent in Hong Kong, and would briefly enjoy the highest salary of any employee of the Alberta government. Meanwhile, for his sins, Charlebois was punished by . . . becoming the executive director of the party in 2012.

And so he took centre stage again late in the 2015 campaign, when former PC candidate Jamie Lall accused Charlebois of blocking a possible run against Wildrose floor-crosser Bruce McAllister for the nomination in the suburban Calgary riding of Chestermere-Rocky View. Emails handed by Lall to the Metro newspaper’s Jeremy Nolais left the impression that Charlebois was personally arranging party nominees like stones in a game of Go: “I don’t want you in Chestermere”, Charlebois told Lall, suggesting that maybe Calgary-Varsity would be a better choice.

Related: Why the Orange Revolution is not about Rachel Notley

The Lall “scandal,” which saw the spurned candidate launch an independent spoiler campaign, reflects the centralized power that is typical of contemporary Canadian political parties. Or, heck, all political parties. The issue, for informed Alberta voters, was that Prentice seemed to be doing his dirty work with the same old cast of characters, and that the old guard always seems to be looked after.

The Conservatives put out word that Lall had been disqualified over a history of stalkerish behaviour toward an old girlfriend, who declared publicly that the matter has been amicably settled. That allowed the opposition forces on social media to point out that the party had not been quite so strict about Mike Allen, your incumbent PC candidate in Fort McMurray-Wood Buffalo, who was convicted in 2013 of trying to rent a pair of prostitutes—not one, but two—while on a government trip to St. Paul, Minn.

At virtually the same moment Lall’s grievance was being aired in the papers, Justice Minister Jonathan Denis, who made a cameo in Lall’s leaked emails with warnings that the PC cabal was out to get him, had to step aside from his portfolio (but not his candidacy) when his estranged wife’s ultimately unsuccessful request for an emergency protection order came before the courts.

This may all sound like inside baseball, but the Progressive Conservative party is, by nature and design, a network whose nodes are tangled up with every aspect of Alberta life. Every Alberta native has had relatives or friends who are connected to the Party, who made a living out of working ethnic or political connections for a returning officer’s job or a seat on some charitable board. In that sense, jests about Alberta’s monolithic, authoritarian nature are not without their sting: it’s a world divided, to some degree, into Orwell’s proles, Inner Party, and Outer Party.

Albertans were fine with this as long as the chocolate ration was increasing. But they have been aware, even if it is just through hints in local weeklies and on the Internet, of the organizational chaos and the declining internal morale that Jim Prentice failed to rectify. And the oil-price tumble is just starting to make service jobs in the oil field disappear.

The PCs kept dribbling out messages of confidence late in the campaign, even as the much-distrusted polls showed the New Democrats surging across the province—running strong in suburban and rural areas in which the NDP brand and machinery hardly exist. Even though the 2012 vote was seen as a failure for pollsters, they did, at that time, offer some evidence of a late surge toward the familiar incumbent. On this occasion, the last-minute polls suggested that voters were scurrying even further and faster away from the PCs.

The Conservative effort to leverage fear of the New Democrats, increasingly rendered difficult by demographic fundamentals, positively backfired. Businessmen who got together to write an open letter calling on voters to “think straight” and return to the PC fold were catcalled as pork-gobbling shills. The Postmedia dailies in Calgary and Edmonton endorsed Prentice in unison, but the editorials were so tortured and surprising that readers immediately smelled a rat, and Edmonton Journal editor Margo Goodhand had to admit that her paper’s piece, which broke with a tradition of refraining from political endorsements, was written on orders from corporate headquarters in Toronto.

Nominally conservative parties still have a majority of the votes between them in Alberta: the nature of the place has not changed overnight. The unrevolutionary, cautious nature of the successful NDP platform shows that. So does the NDP’s campaigning on the economically dirigiste legacy of Peter Lougheed, the politician that Rachel Notley’s father—Grant Notley, provincial NDP leader from 1968-84—spent his life fighting. The New Democrats tried very consciously to appear as the equivalent, if not the rebirth, of the Progressive Conservatives of 1971—a future-oriented youth party ready to take over from the mouldy oldies, while continuing their track record of working-class prosperity.

They and the wounded Wildrose were able to put the squeeze on the most natural of all natural governing parties because there was not much daylight between any of them on fundamental issues. The NDP and the PCs agreed on the need to save more resource revenues and get Alberta “off the boom and bust cycle”—easily done, so the joke goes, by eliminating the booms. They agreed on the need to get rid of the flat tax. They agreed on the need to create more oil-refining jobs in Alberta, and also on the need to diversify the Alberta economy away from oil. That may sound like a contradiction, because it is, but both halves of it are popular with Albertans.

Wildrose Leader Brian Jean sent a different message—that the growing PC debt could be covered by reducing managerial waste and eliminating sole-source contracts with government cronies, rather than by raising taxes. In other respects, he basically proposed to run a Klein-era PC government, with different personnel, instead of a Lougheed-era one.

Perhaps not coincidentally, this is the first Alberta election in which neither of those ex-premiers was on hand to speak up for himself. Lougheed and Klein were the opposing poles of Alberta politics for quite a while: patrician and populist, uncommon man and uncommonly common man, large-P Progressive and large-C Conservative. The Alberta PCs have finally, it seems, been torn apart between the two tendencies that they were created to reconcile. Nothing will ever be the same—and yet everything will, for whatever particular sort of government crawls out of this magnificent mess of an election, there are still mountains to be skied down, cattle to be fed, rivers to fish, and bitumen to dig up.