The view from Donald Trump’s hometown: ‘It’s gonna get uglier.’

Allen Abel travels to Donald Trump’s hometown to check in on the state of the campaign

Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump arrives for a campaign rally at Crown Arena, Tuesday, Aug. 9, 2016, in Fayetteville, N.C. (AP Photo/Evan Vucci)

Share

The house where Donald Trump learned to toddle is a tired Tudor on a tidy street, fronted by a For Sale sign, a weary little garden and a wilted flag on a tilted pole. A few blocks to the north, a honk-and-snarl freeway leads from the humble domiciles of the borough of Queens to the Daddy Warbucks skyscrapers of Manhattan. To the south is the terminus of the F train of the New York City subway, screeching midtown-bound.

Half a century ago, the snarling, sneering man who still may become the 45th president of the United States bolted from Queens to Broadway and never glanced over his shoulder at the little people he left behind. But unlike Trump, the millions of commuters who essay that maddening journey by rail or road each morning must return to the outer boroughs at night.

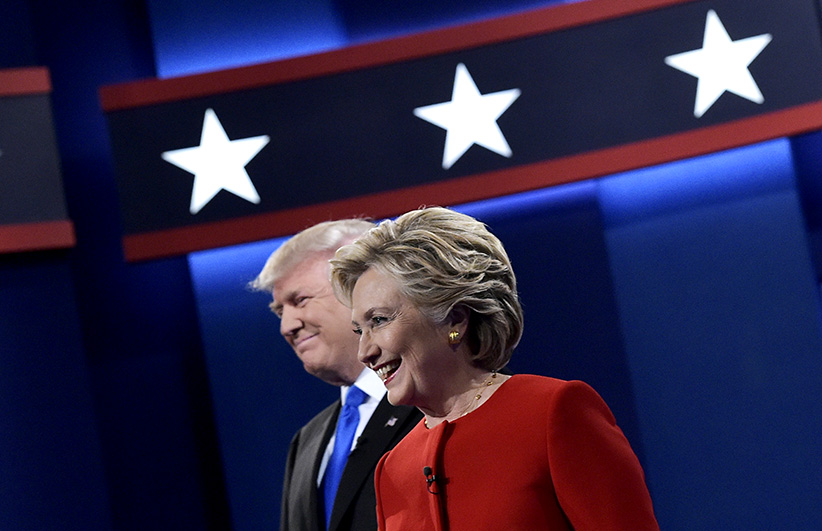

Here on Wareham Place, in the leafy enclave called Jamaica Estates where Trump’s father, Fred, built his family’s first two homes—the second was a 10-bedroom hillside palace of stately brick and tall, white columns, immediately behind the little Tudor, where Donald and his siblings spent their public school and teenage years—the candidate’s erstwhile neighbours awakened Tuesday morning with the slander, spin and sliminess of the first debate between Trump and former secretary of state Hillary Clinton still ringing in their ears.

One of them was a woman named Renee Corkrum, who was walking a shih-tzu named Lexington toward Trump’s natal address. “I think that Trump was not prepared,” Corkrum said, echoing the opinion of the vast majority of American voters who tuned into the first of three Debates of the Century between the two elderly heavyweights. (The second clash will occur in St. Louis on Oct. 9; the finale 10 days later in Las Vegas.) “He is not abreast of the issues. His body language and his expression were very rude, and his constant interruption was not very presidential-like.

“But even then, he could have swayed me. I did not want to vote for Hillary Clinton as the lesser of two evils. I am not a big fan of Hillary Clinton—something about her is a little sneaky, and I still question why she didn’t give Bill more of a hard time about his cheating—but she swayed me last night.”

“For the first 15 minutes, I thought Trump held his own, but then she took over,” a man named Kensley Charles agreed, after wrangling his car between a driveway and a fire hydrant in accordance with New York’s infuriating alternate-side-of-the-street parking rules. “But all those jibs and jabs that they were throwing at each other—politicians are supposed to be about leadership—that is something that you cannot condone.”

Charles said that he remains persuadable as the campaign enters its final month. “As a black male, maybe that’s surprising,” he confessed, “but I’m not decided due to the behavior of both of them. I want to hear them talk about national security, how they’re going to make our country feel safe and our city feel safe, and how they’re going to take the guns away.”

“Terrorism needs to be worked on,” Corkrum said. “Unemployment needs to be worked on. This country’s too great to have so many homeless people.”

“Two more debates,” she sighed, picking up after her pooch. “It’s gonna get uglier.”

“I’ve been through racial profiling,” Charles said. (The stopping and frisking of young men of colour had been the subject of an unusually sober segment of the debate, with Trump praising the practice while spewing patent untruths about its efficacy and legality.) “In high school and even in junior high school, I’ve been stopped and told ‘You look like a suspect in an armed robbery.’ But I didn’t let that determine the course of my life. To me, it’s all about temperament —your own, and the people who are running for office. If the election was determined by what was said last night, I’d go for Hillary. But anything could happen next.”

Now a black sedan pulled up in front of the Trump mini-castle and inside were two students from Hunter College, heading for the F train. The driver was a computer science major named Aousafun Nabi Khan, the son of immigrants from Bangladesh.

“After watching the debate, I don’t really support any of them,” Khan said. “Trump is not a man of his word. I basically think he’s a joke. Hillary is pretty OK compared to Trump, but I am supporting Bernie Sanders.”

“You’re too late,” the student was informed. “Bernie’s gone.” (But not forgotten. The Vermont socialist was to campaign at Clinton’s side in New Hampshire on Wednesday on behalf of her—formerly his—promise to make a public university education free for any child whose parents earn less than US$125,000 a year.)

Related: Scott Feschuk has tips for Donald Trump during the next debate

“It doesn’t matter because I am not yet a citizen,” the Hunter collegian replied. “I cannot vote yet, but if I could vote, I wouldn’t.”

More than 80 million Americans watched Trump call Clinton a “typical politician. All talk, no action. Sounds good, doesn’t work.” Clinton invited Trump to “just join the debate by saying more crazy things.” The confrontation easily beat Monday Night Football, but it was the football game that had the Saints.

As a clash of intellects and philosophies, the presidential debate fell short of the Socratic ideal. But as theatre, it was Tony Award-calibre:

Trump: “But you have no plan.”

Clinton: “Oh, but I do.”

Trump: “Secretary, you have no plan.”

Clinton: “In fact, I have written a book about it. It’s called Stronger Together. You can pick it up tomorrow at a bookstore…

And:

Clinton: “We have an architect in the audience who designed one of your clubhouses at one of your golf courses. It’s a beautiful facility. It immediately was put to use. And you wouldn’t pay what the man needed to be paid, what he was charging you to do…”

Trump: “Maybe he didn’t do a good job and I was unsatisfied with his work.”

Clinton: “And when we talk about your business, you’ve taken business bankruptcy six times. There are a lot of great businesspeople that have never taken bankruptcy once. You call yourself the king of debt. You talk about leverage. You even at one time suggested that you would try to negotiate down the national debt of the United States.”

Trump: “Wrong. Wrong.”

And:

Trump: “We have no leadership and honestly that starts with secretary Clinton.”

Clinton: “I have a feeling by the end of this evening I’ll be blamed for everything that’s ever happened.”

Trump: “Why not?”

Clinton: “Yeah. Why not?”

Other words the 80 million heard: “stiffed,” “slobs,” “stamina.”

Words they never heard: “Obamacare,” “border wall,” “refugees,” “Aleppo.”

And, at the denouement:

Moderator Lester Holt: “Will you accept the outcome of the election?”

Trump: “Look, here’s the story. I want to make America great again. I’m going to be able to do it. I don’t believe Hillary will. The answer is, if she wins, I will absolutely support her.”

On Feb. 26, 2008, senators Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama debated in Cleveland in advance of that state’s Democratic Party primary.

“Why won’t you release your tax return,” moderator Tim Russert asked Clinton, “so the voters of Ohio, Texas, Vermont, Rhode Island know exactly where you and your husband got your money, who might be in part bankrolling your campaign?”

Clinton: “Well, the American people who support me are bankrolling my campaign. That’s—that’s obvious . . . I will release my tax returns. I have consistently said that. I will—”

Russert: “Why not now?”

Clinton: “Well, I will do it as others have done it: upon becoming the nominee, or even earlier, Tim, because I have been as open as I can be.”

Russert: “So, before next Tuesday’s primary?”

Clinton: “Well, I can’t get it together by then, but I will certainly work to get it together. I’m a little busy right now; I hardly have time to sleep.”

Clinton released her returns in April of that year. Fast forward to Monday night, and Clinton was pressing Trump: “You’ve got to ask yourself, ‘Why won’t he release his tax returns?’ ”

“I will release my tax returns . . . when she releases her 33,000 emails that have been deleted,” said Trump.

Richie’s Place is a coffee shop on Hillside Avenue, just down from the tired Tudor house on Wareham Place. Hillside is where Trump and his buddies used to hop on the F train to go into the city and search out the kind of excitement you can’t find in Jamaica, Queens.

Orlando Rodríguez and Francisco Cintrón were sitting in a booth by the window, the morning after the debate. Above them, the television was blaring the news of the day in the Greatest City in the World: a fire chief dead in an explosion in the Bronx; a bus crash in the Lincoln Tunnel; major delays on the F train in Coney Island.

The house on Wareham Place, the men had noticed, still was up for sale, even though the asking price had been slashed from US$1.65 million to only a million-four. In fact, it is going to be auctioned to the highest bidder on Oct. 19, the same day that the little tyke who toddled there will get his third and final shot to pierce the armour of Hillary Clinton out in Vegas, which is about as far from Hillside Avenue in terms of glitziness as you can get.

“They must think he’s gonna lose,” the men laughed, “or else they’d sell it after the election, when it would be worth a lot more money.”

Like many millions of their fellow citizens, Rodríguez and Cintrón had watched the debate on Monday night with a combination of morbid curiosity and gathering disgust.

“He’s gonna release his taxes, he’s not gonna release his taxes—who cares?” Rodríguez snapped, the morning after. “Who cares?”

“Or Hillary, how many email messages she erased—that’s not important.”

“What’s important is who’s gonna move this country forward,” said Cintrón.

“Hillary’s no better than Trump, and Trump is no better than Hillary,” said Rodríguez. “He’s more concerned about his finances than anything else.”

“At the end of the day, he’s got his money, he’s got his bodyguards, he’s got his life,” agreed Cintrón.

The men walked outside to the sidewalk, where you could see sari shops and halal butchers and Korean fruit stands and Dominican groceries and the beautiful fabric of the world that Trump, the developer’s son, had left behind, so many years before.

Then they grew quiet.

“If he does win,” Rodríguez prophesied, “in six months, I guarantee you—we’ll be at war.”