The transformation of Pierre Karl Péladeau

Leading a decimated Parti Québécois might not be a plum assignment but PKP may just bite

Pierre Karl Peladeau

Share

About four years ago, from a podium flanked by Canadian flags, Pierre Karl Péladeau stood in front of a roomful of journalists and proclaimed his concern for the state of his country’s democracy. The president and CEO of Quebecor, one of the country’s largest media corporations, said Canadians were almost dangerously ill-served by the country’s existing television news channels. “Far too many Canadians are tuning out completely or changing their dials to American all-news channels. They’re opting out or switching over. That’s not good for Canadian television. It’s not good for Canadian democracy. And it’s not good for Canada itself,” Péladeau said.

His solution to this tragedy was Sun News TV, a “controversially Canadian” television network that would be as pithy and populist as the CBC was prissy and politically correct. The channel’s combination of punchy news coverage and unfettered opinion—“Hard News, Straight Talk”—would stoke the country’s typically quiet patriotism into a proud, pan-Canadian flame. Péladeau expected to lose money on the venture, but no matter: “Canadian democracy will suffer” without a diversity of voices, he said.

Today, Péladeau is the early frontrunner to lead the Parti Québécois, a separatist party that seeks to end this rosy take on Canadiana. Péladeau remains Quebecor’s majority shareholder, meaning the nearly five million presumably patriotic Sun News subscribers are sending their dollars to a man now dedicated to dismantling the country that the channel proudly serves.

Behind this delicious irony is the transformation of Péladeau from an at-times shrill Canadian nationalist to a would-be saviour of the Parti Québécois. Without a permanent leader since the party’s decisive electoral defeat last April, the PQ is at yet another, perhaps final, ideological and existential crossroads.

Parti Québécois membership will only choose a new leader next spring, and party brass has yet to outline candidacy rules. Remarkably, though, Péladeau is the leading contender amongst the six Péquiste MNAs thought to be eyeing the position—despite having been publicly associated with the Parti Québécois for all of six months.

Péladeau himself has remained mum on his leadership intentions. “Unfortunately, I am not available,” he wrote to Maclean’s in an email when asked to comment. Yet according to a PQ source, Péladeau has the unspoken backing of the party’s interim leader, Stéphane Bédard. (Bédard’s brother Éric is Péladeau’s lawyer.) As the province’s most prominent businessman, he also has name recognition that goes beyond the cloistered world of politicos and journalists. “He hasn’t said a word, and yet everybody talks about him,” says former union leader and long-time PQ activist Marc Laviolette.

As ingrained as he has become within the Parti Québécois, Péladeau’s decision to enter politics, if not his conversion to the separatist cause, was typically impulsive. As recently as July 2013, Quebecor spokesperson Martin Tremblay brushed off suggestions that his boss was a sovereignist. Rather, Tremblay said, Péladeau was an “economic nationalist” who counted former prime minister Brian Mulroney as a mentor and business partner.

When then-Quebec premier Pauline Marois began courting Péladeau around that time, Péladeau vociferously denied any intention of entering politics—only to jump into the fray once the election had begun last March. His decision sent PQ organizers scrambling, and his campaign signs weren’t even ready in time for his announcement. Yet he stepped in with great gusto, raising his hand in the air during his inaugural address as a PQ candidate, declaring he was here to “make Quebec a country.”

Today, his personal email address uses the name of Curé Antoine Labelle, the famed 19th-century priest best known for colonizing the vast countryside north of Montreal—the very territory where Péladeau holds a seat. Like Péladeau, Labelle was conservative and ambitious. And Labelle’s nickname, “King of the North,” isn’t likely a coincidence either.

Péladeau’s infamous impulsiveness has again reared its head since he was elected. Péladeau the businessman waged a protracted six-year battle against the CBC and Radio-Canada, claiming government-funded media was unfair competition to his myriad private television and Internet holdings. Yet Péladeau the politician protested loudly at the Conservative government cuts to those same government-funded media. “Information is not just merchandise,” he wrote in an open letter last May.

There’s further evidence that Péladeau is tying up loose ends. He has buried the hatchet with several well-known Radio-Canada personalities with whom he’d waged war over the years—and who pull considerable weight in Quebec’s cultural and political circles. He also reconciled with Julie Snyder, the mother of his two youngest children and a formidable TV personality in her own right. Péladeau travelled to Scotland to observe the recent referendum, and lamented to a Quebecor journalist how “we don’t talk about sovereignty anymore.”

Six PQ MNAs, or roughly 20 per cent of the party caucus, are vying for the leadership. Péladeau’s rivals are considerably to his left. Péladeau’s political bent will cause him problems should he indeed run for the leadership, according to a one prominent sovereignist.

“Péladeau’s problem is that he has put his eggs in two baskets. He wants to lead a historically centre-left party, yet he’s close ideologically to Stephen Harper,” says former Bloc Québécois MP Jean Dorion. In a former life, Péladeau and Snyder dined with Harper and his wife Laureen. In 2009, according to a Conservative source, the Conservatives wanted to appoint Snyder to the Canadian Senate. She declined, and the party ultimately picked former Canadiens hockey coach Jacques Demers.

Péladeau and the PQ are certainly an odd fit, even for a man used to ideological contortions. The PQ is a social democratic party much in the mould of its founder (and Quebec’s reigning secular saint), René Lévesque. Under successive Parti Québécois governments, Quebec became a haven for organized labour. Because of this, nearly 40 per cent of its labour force is unionized today, a fact Péladeau the businessman often bemoaned.

He was responsible for 14 lockouts of his unionized employees during his Quebecor reign, according to union statistics. “He is probably one of the worst employers Quebec has ever seen,” read a news release last May from FTQ, Quebec’s largest union federation.

While the PQ itself has drifted to the right over the years, its powerful membership core, which number upwards of 90,000, remains largely leftist and union-dominated. Marc Laviolette supported Péladeau’s run for office during the election, but says he wouldn’t want Péladeau as PQ leader. “I think he is a good first violin but he’s not a conductor,” says Laviolette. “Right now, the party needs a unifier, and given Péladeau’s past, I don’t think he qualifies.”

Péladeau will face an even more daunting challenge should he become PQ leader. The party has been at war with itself since last April’s electoral debacle, its worst showing in terms of popular vote in its 46-year history. Québec solidaire, a rival sovereignist party, has seen its youth membership swell, which party officials say is due to the PQ collapse. The president of upshot separatist party Option Nationale, Nic Payne, recently told Maclean’s that the PQ approach was “dead,” while former PQ leader Jacques Parizeau said the party had led the sovereignty movement to “a field of ruin.”

Péladeau, though, has one huge advantage over his leadership rivals—and not only because the leadership fee is rumoured to be $35,000. An unbelievably wealthly political neophyte, Péladeau’s legitimacy lies in his own decision to run for the Parti Québécois, a party in which headaches and constant struggle are not in short supply. “As his supporters point out, Péladeau’s story practically writes itself if he runs,” says Dorion.

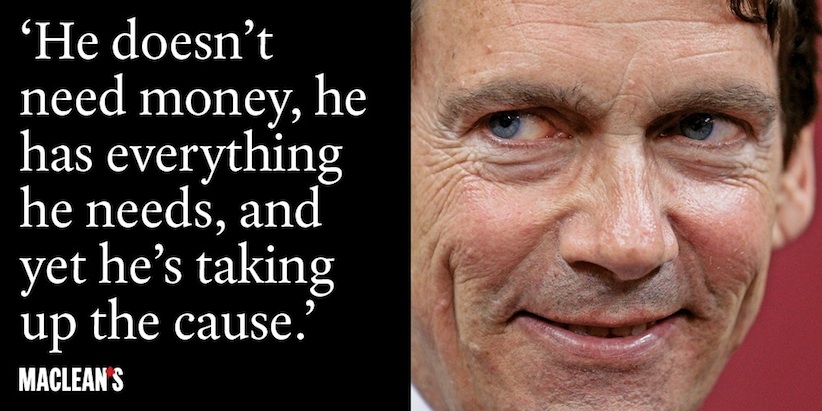

“He doesn’t need money, he has everything he needs, and yet he’s taking up this cause.”

Perhaps Péladeau has found his calling in fighting against all odds for a new country.