The year that bloated bureaucracy took a back seat to getting things done

The pandemic forced a culture shift in governments that usually move slowly on purpose, proving that red tape really can be cut

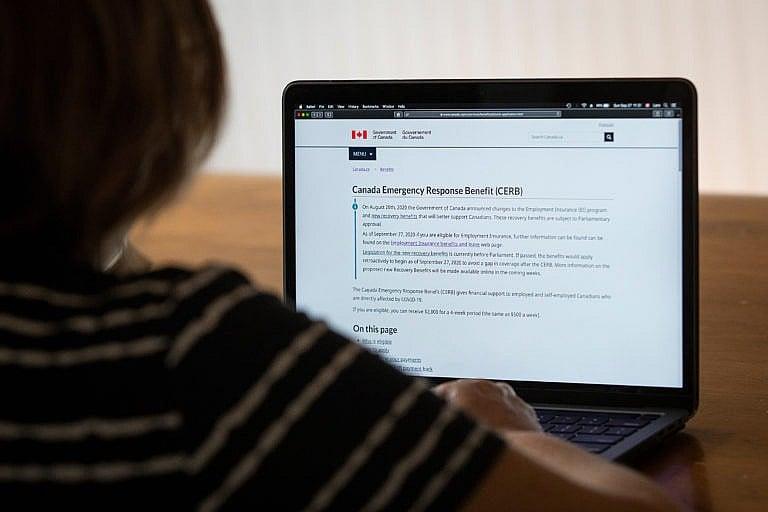

Politicians and public servants worked long hours to churn out the CERB in record time (Lars Hagberg/CP)

Share

This has been a year of realizing that what we thought was solid ground beneath our collective feet was in fact a cliff that would crumble away with just a bit of natural erosion or one sharp blow. We reflected on 2020 to find truths, exploded. This is one of them. Read more about the year that changed everything »

When governments get something right, generous politicians sometimes give the credit to hard-working public servants. Occasionally, they refer to them, with some reverence, as civil servants. The word bureaucrat, by contrast, is a bit of an insult, a nod to the scourge of oversized, lumbering bureaucracy mummified in red tape. Before the pandemic, went the stereotype, bureaucrats and their endless systems slowed everything down, and intentionally so. They reduce risk to zero, check every box and meet every approval, haste be damned.

Then COVID-19 happened.

In March, amid widespread economic shutdowns, governments across Canada slapped together recovery programs in record time. Within weeks, millions of Canadians had applied for the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) that deposited $500 into their bank accounts every week. Politicians and public servants worked long hours—and often weekends—to produce the CERB and a suite of programs meant to help workers and their employers endure the crisis with no end.

OUR EDITORIAL: Looking at truths, exploded

Mistakes were made as the feds and their provincial counterparts tweaked programs that were developed without the benefit of comprehensive risk assessments and consultations that typically last several months before a program comes to life. A federal-provincial rent-relief program that required landlords to apply fell far short of its targets. The failed student service grant produced the sticky summertime WE Charity scandal.

In April, Employment Minister Carla Qualtrough told Maclean’s that she expected hiccups. “We should be more comfortable with higher levels of risk, but I think we also have to sensitize the public to it being okay to course-correct in government, and trying things that are a little bit more bold or risky,” she said. “But that’s a real culture shift for both the politicians and the public service.” Qualtrough was acutely aware of the stakes. “Governments have fallen when things haven’t worked out,” she said, unaware at the time that the WE scandal and assorted other controversies would eventually trigger a high-drama confidence vote in October.

Sean Mullin, the executive director of the Brookfield Institute for Innovation + Entrepreneurship and a senior adviser to former Ontario premier Dalton McGuinty, says governments had no choice but to take chances as the economic crisis hit Canada. “A lack of speed was the biggest risk,” he says, adding that missteps tended to be on more “obscure, complicated” policy challenges like rent relief. Mullin hopes policy-making processes transformed by the health and economic crises don’t simply return to normal. “They forced change that’s hard to reverse,” he says, pointing to virtual doctor’s appointments, homework submitted by email and even on-demand delivery of alcohol in Ontario. Those all required innovative thinking on the part of an army of so-called bureaucrats.

The pandemic response also required thousands of federal workers to rethink how they work together. Taran Wasson, a federal public servant who chairs the national capital chapter of the Institute of Public Administration of Canada, credits a common instinct simply to contribute to the national effort—a “belief in helping.” In March, everyone suddenly had the same priority. “There’s a switch that flipped,” he says. But Wasson was quick to point out that governments don’t show up only in case of emergency. “This is a job we do every day,” he says. “Not just during a crisis.”