There is peace in space. But will earthly conflicts end it?

U.S.-Russia relations continue to deteriorate. And the International Space Station’s survival is at stake.

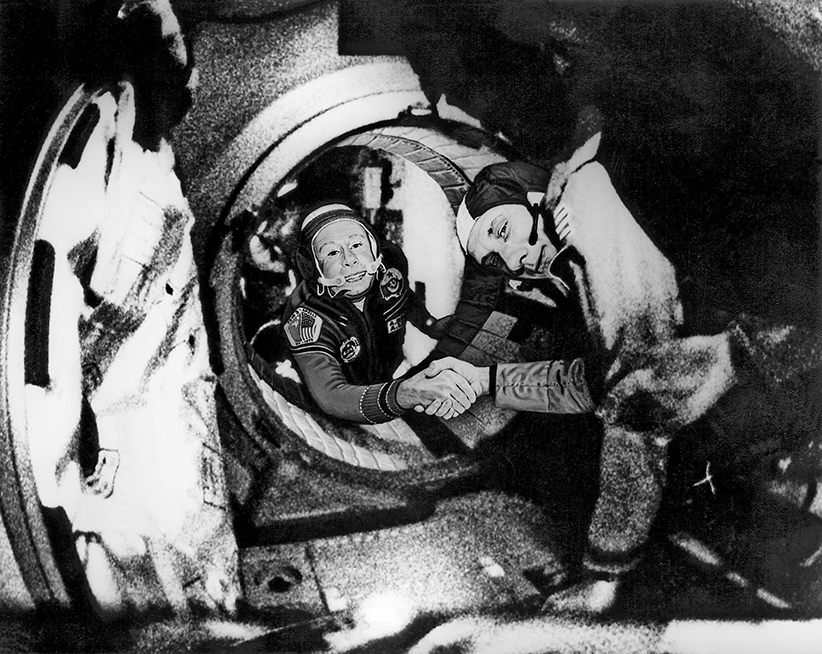

Commander of the Soviet crew of Soyuz, Alexei Leonov (L) and commander of the American crew of Apollo, Thomas Stafford (R), shake hands 17 July 1975 in the space, somewhere over Western Germany, after the Apollo-Soyuz docking manoeuvres. (AFP/Getty Images)

Share

The skies were clear over central Kazakhstan in the wee hours of March 25, 2014—so cloudless that U.S. astronaut Richard Mastracchio could peer from his perch in the International Space Station (ISS) and watch the launch of the Russian-made spacecraft bringing a crew of three to join him. Like Mastracchio, the trio aboard Soyuz TMA-12M were avatars of the co-operative spirit that brought the station into being: two Russians and an American, all grins and uplifted thumbs, as they blasted toward the stars on a perfect night for a rocket trip.

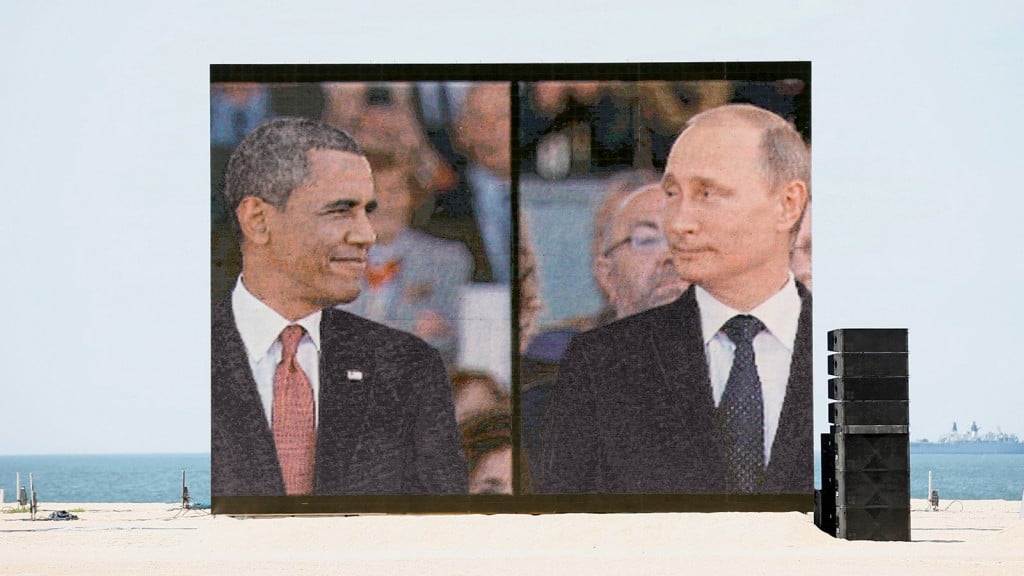

On this night, though, the obligatory show of camaraderie was noteworthy, because conditions in the diplomatic sphere were less than favourable. Even as the crew of Expedition 39 locked arms for some final, pre-launch photos, U.S. President Barack Obama was working the phones, trying to forge a non-military response to Russia’s recent annexation of Crimea. The result: a decision the following day by G8 leaders to punt Russia from their club of global economic heavyweights, along with a stinging joint statement accusing Moscow of violating “the principles upon which the international system is built.” Sergey Lavrov, Russia’s foreign minister, was tart in response. “The G8 is an informal organization that does not give out membership cards,” he told reporters. “By its definition, it cannot remove anyone.”

Related: Our annotated interview series with Canada’s astronauts

Escalating economic sanctions by the U.S. followed and by the end of April, when Washington announced a ban on high-tech exports to Russia, Dmitry Rogozin, Russia’s deputy prime minister, had tossed aside a longstanding taboo against dragging the ISS into terrestrial disputes. Noting that the latest measures seemed aimed at Russia’s space-related industries, he made a none-too-subtle reference to NASA’s reliance on Russia to get its people into orbit, tweeting: “I suggest the U.S. delivers its astronauts to the ISS with a trampoline.”

Rogozin was in no position to back up his rhetoric. The U.S., after all, has pumped billions into his country’s space program, including payments for Americans’ seats on the Soyuz. (A renowned bloviator, he’s left numerous threats unfulfilled.) And it’s not as if his space agency, Roscosmos, can operate the ISS without the U.S.

Still, those heated words from a Vladimir Putin confidant laid bare tensions straining the fabric of the Russia-U.S. space partnership. Can it survive as relations here on the surface deteriorate? Is mutual dependence enough to hold it together? What happens after the ISS agreement expires? If the two sides part ways, will each honour its long-standing commitment to use space for peaceful purposes?

Mutual need, it must be said, has long been a cornerstone of this once-unthinkable relationship. The economic crisis that followed the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 had put Russia’s once-proud space program in peril, stalling the expansion of its pioneering Mir space station. NASA faced its own budget cuts with the end of the Cold War, yet was keen to tap the knowledge Mir crews had gathered about the challenges of long-duration manned space flights, which would be necessary for interplanetary travel. So, in 1992, the presidents of the two countries, Boris Yeltsin and George H.W. Bush, announced a deal under which astronauts and cosmonauts would serve together on Mir and NASA space shuttles, learning each other’s language, wearing each other’s space suits, operating each other’s equipment. The arrangement injected much-needed cash into the newly created Russian space agency. It also set the table for the multinational project now known as the ISS, announced the following year.

Reducing the partnership to a marriage of financial convenience, though, ignores the genuine sense of hope that shared projects in space have inspired in both countries—an optimism that seems to blossom during periods of détente. The ISS idea was first conceived during a mid-1970s lull in the Cold War, when the Soviets and Americans completed their first joint mission by docking an Apollo spacecraft to its Soyuz counterpart on July 17, 1975. In a euphoric moment known as the “handshake in space,” Soviet mission commander Aleksey Leonov reached through the open hatch of the Soyuz and grasped the palm of Thomas Stafford, his American counterpart. “We estimate that a billion-and a-half people around the world saw me shake hands with Aleksey,” Stafford recalled last month during a 40th-anniversary commemoration of the occasion, with Leonov at his side. “If people like us could work together, we could work together on a lot of things.”

Related: How India transformed from space underdog to surprising giant

Two years later, the countries signed an agreement that would have seen NASA’s shuttle, then in its early test phases, dock on Mir, while the two sides worked together to develop a joint space station. Only U.S. anger over the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan derailed the plan, says John Logsdon, former director of the Space Policy Institute at George Washington University in Washington, adding, “This is a piece of space history that very few people know.”

Given recent events, it seems an instructive one. Yuri Karash, a Moscow-based space policy expert and a member of the Russian Academy of Space Sciences, believes two conditions must apply for U.S.-Russian space partnerships to succeed. For starters, he says, Russia must have something tangible to contribute—be it experience, hardware or technology. More important, though, is political harmony between governments.

The first condition is very much in question. Russia has developed little in the way of groundbreaking technology and hardware in recent decades, notes Karash, and has endured two spectacular rocket-launch failures in the past four months that have shattered confidence throughout Roscosmos. Relations between the two governments, meanwhile, are arguably at their worst since Soviet boots were tramping through Afghanistan. “I’m sure that Russia and the United States will continue co-operating in the ISS program,” he stresses, noting that both have committed to the ISS until 2024. “But, in the long term, I think such bad relations [over events such as the Ukraine conflict] will have an extremely detrimental impact on the bilateral relationship in space.”

It’s a view many astronauts and cosmonauts find hard to hear, because, with few exceptions, they’ve overcome language barriers, political differences and misgivings about each other’s space programs to do their jobs. In the midst of the contretemps over Crimea, cosmonaut Oleg Kotov, who’d recently returned from the ISS, publicly urged co-operation, declaring: “All such missions need to be international, because each country has its own experience, skills and knowledge. Combining all those assets will help us develop deep space.”

That faith did not come easily. Jerry Linenger, a member of the Shuttle-Mir program of the 1990s, recalls U.S. Navy F-14s escorting Soviet bombers away from American carrier groups in the Indian Ocean during his pre-astronaut days. “A few years later,” he recalls, “I’m on Mir with two Russians, neither of whom speaks much English, for months on end. One’s a former military engineer. The other used to fly MiG fighters out of East Germany. Yet we got along.”

For astronaut Norman Thagard, Cold War history was less a worry than the effect that post-Soviet chaos might have on Russia’s space program. He was preparing to become the first American to fly aboard Mir in October 1993, when a constitutional crisis gripped Russia, leading to an armed uprising in Moscow against Yeltsin’s still-shaky new government. He watched the mayhem unfold on TV at the Defense Language Institute in Monterey, Calif., where he was learning Russian. “I was thinking, ‘I’m going into the middle of what may be a civil war,’ ” he says.

Yeltsin fought off the coup, of course, and when Thagard reached Star City, the district outside Moscow where cosmonauts learn their craft, he was relieved to find an atmosphere of stability and rigour. Training methods closely resembled those at NASA, he recalls, while the Russians handled their Western guests with a kind of bemused tolerance. “To them, we were Americans,” Thagard says. “But we were their Americans.”

In short, the astronauts’ behaviour in space provided a real-time model of how their governments might co-operate: focusing on shared goals and leaving aside issues that—however vexing on Earth—are irrelevant to life in orbit. It still does. But tensions over Ukraine have weighed on the joint program. The U.S. sanctions announced last spring, for example, forced NASA to suspend all work with the Russian space industry not directly related to the ISS. Moscow, meanwhile, has announced a consolidation of its aerospace industries and space programs under the umbrella of Roscosmos, an administrative model more closely resembling the command-and-control system of the Soviet era.

Related: Is this the spacesuit of the future?

All this has fuelled speculation that both countries are ready to move on. In Russia, Rogozin mused openly in May 2014 about bailing out of the ISS program as early as 2020, complaining that it consumes 30 per cent of Roscosmos’s budget. Again, the deputy PM’s tone was more illuminating than his content: In the past few weeks, Russia has recommitted to the ISS until the end of 2024, while NASA has dedicated $490 million to pay for Soyuz seats until the end of 2018.

In Washington, meanwhile, attitudes toward the ISS partnership can best be described as divided. On one hand, pressure is growing to end U.S. reliance on Soyuz transport to the ISS, which has held since the shuttle program was shut down in 2011. NASA had hoped that private contractors such as Boeing and SpaceX, an upstart led by billionaire entrepreneur Elon Musk, could be filling that need by 2017.

But the high-profile failure in June of a SpaceX rocket scheduled to deliver supplies to the station called that target into question. And a recent decision driven by congressional Republicans to slash $300 million from that program’s funding seems, if anything, a slap in the face to ISS crew members waiting on the next successful supply launch.

Whatever the solution to the ISS transport conundrum, one thing is clear: The next big U.S. space exploration project will not involve joint operations with Russia. Cynicism about the partnership has been on the rise in Washington since Rogozin’s last outburst, and Russia hasn’t helped its cause by jacking up the fee it charges the U.S. and other ISS partners—Canada, the European Union and Japan—for seats on the Soyuz. Since 2006, it has almost quadrupled its rate to US$81 million. Considering how long the Soyuz technology has been around, one might reasonably think it should be getting cheaper.

Related: Guest editor Chris Hadfield’s essay on space exploration

At the same time, both NASA and the Obama administration are increasingly preoccupied by the country’s on-again/off-again Orion project, which would see a manned spacecraft land on an asteroid as a stepping stone to sending one to Mars. The program, projected to cost $21 billion, has support from Obama, and a whole lot of critics in Congress. No one imagines it as anything but an America-only project.

To observers such as space historian Robert Zimmerman, it all points to numbered days for the internationalist model of space exploration, which he believes values politics and diplomacy over innovation and ambition. Programs such as the ISS partnership, he says, inevitably become “geopolitical footballs” used by the parties to extract favours, money or international recognition. “You don’t get any engineering innovation, you don’t get any competition for achievement,” says Zimmerman, whose book Leaving Earth chronicles the 20th-century space race up to the current phase of ISS co-operation. “You don’t get any desire to do new things.”

Linenger, the former U.S. astronaut, agrees. Some crew members on the Shuttle-Mir missions, he says, understood “that the science was not really all that important and the over-arching objective was just not to rock the boat.” The root of the problem, he says, lies in the fundamental difference between the scientific and political spheres. Whereas space travel is based on essential truths of physics—“a logic-driven endeavour, driven by logically thinking people”—politics rewards obfuscation, oversimplification and hyperbole. Decisions get made through compromise, Linenger says, and “good-enough solutions do not work in the extremes of space.”

Which, if true, raises the question: Should they keep trying? Can the promise of the Russian-U.S. partnership be salvaged, and applied to exploration programs that come after the ISS?

Logsdon, the George Washington University expert, believes the tensions within the ISS partnership have been exaggerated. The price of a Soyuz seat, he notes by way of example, is “not that much” when one considers the billions required annually to operate the space shuttles. But he also believes the ISS partnership brought us to a teachable moment. While the spirit of competing countries working together in space must continue, he says, the ISS model of close interdependence likely won’t work in big space projects to come. The U.S. will, presumably, take the lead in those programs by dint of its massive space budget, Logsdon notes, and strategic considerations will inevitably assert themselves. “How willing are we going to be to put rivals like Russia and China on the path of potential mission success?” asks Logsdon. “I think that’s an open issue.”

Any number of new models might arise, of course, because the spacefaring community is changing so fast. China, which has been left out of the ISS partnership, is planning its own space station, while India has made strides in unmanned, deep-space exploration. Private enterprise, meanwhile, is keen to exploit any commercial opportunities emerging from new projects, in partnership with national agencies or on their own. Zimmerman, for one, believes governments should get out of the way, allowing competitive market forces to spur innovation.

But if the ISS has taught us anything, it’s that alliances among like-minded governments can be enormously productive. For all the press the U.S.-Russia conflict has gotten over the past year, the real story of the ISS may be the bonds it cemented between the U.S. and its other partners.

What’s more, ambitious new exploration missions involve myriad elements requiring development and construction, from rocketry to communication to add-on components, which make them suitable for global partnerships. For that reason, Logsdon believes collaboration will make sense for the foreseeable future, even if it involves asymmetrical alliances—that is, a limited sharing of technology and equipment between rival countries such as the U.S. and Russia, rather than fully merged operations. Maintaining such co-operation may help to head off the militarization of space, he notes, because the basis of any such partnership would be an all-party commitment to use space only for civil purposes.

A partial map for such a way forward is already being drawn. In 2007, 14 national space agencies hammered out a vision for peaceful robotic and human space ventures, resulting in the creation of the International Space Exploration Coordination Group. It’s a mechanism through which member countries can share their goals, interests and plans for exploration, reducing duplication and strengthening each other’s projects. Its starting point is peace, civility and collaboration, and its work has been limited only by the absence of a long-term program of exploration on the part of the U.S.

But the stasis won’t hold. As last month’s successful swing past Pluto by NASA’s unmanned New Horizons probe demonstrated, the old itch to shuck off the bounds of earthly orbit is alive and well. Cheers went up at space agencies around the world as the first images of the dwarf planet rose on screens—an American achievement on behalf of everyone. That the event coincided almost to the day with the anniversary of Leonov and Stafford’s momentous handshake made the celebration all the more poignant. Standing next to his two Russian crewmates on the ISS, Scott Kelly, a U.S. astronaut, might have said it best, declaring that such triumphs “not only brought our nations together, but paved the way for the ISS and the missions yet to unfold that will take us to the stars.” Put thus, it seems too much to throw away.

Get to know the great unknowable. Read Maclean’s special Space issue, on physical newsstands and on Next Issue, Apple Newsstand and Google Play.

Follow @ChasGillis on Twitter

Update