Prince Philip’s funeral: At a service with 30 congregants, the Queen sat alone

Patricia Treble: Those who knew Prince Philip best—his family, friends, staff and military—said goodbye as privately as possible

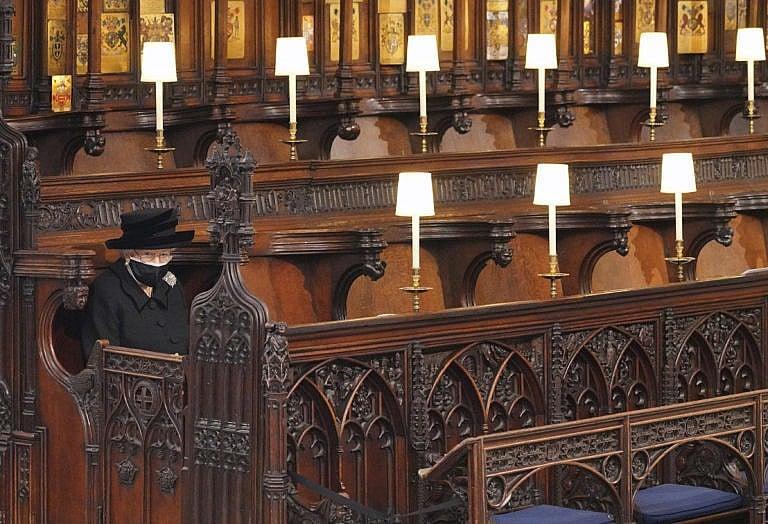

Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II looks on as she sits alone in St. George’s Chapel during the funeral of Prince Philip, the man who had been by her side for 73 years, at Windsor Castle, Windsor, England, Saturday April 17, 2021. Prince Philip died April 9 at the age of 99 after 73 years of marriage to Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II. (Jonathan Brady/Pool via AP)

Share

For 74 years, Prince Philip walked beside his wife, Elizabeth. He was her “liege man of life and limb” and she was the centre of his universe. He headed their family; she, the nation and Commonwealth.

On this day, he took precedence. For more than a year, his family had been scattered by the pandemic. Now, to mark his death, they came together to honour their patriarch and to support their matriarch. The pandemic meant no hugs, no pats on the back. As Philip’s children and grandchildren walked behind his coffin, his widow, Queen Elizabeth II, sat next to her lady-in-waiting in the state Bentley at the rear of the procession.

We are so used to focusing on the “royal” and not the “family” part of “royal family.” This funeral reversed that focus, putting family first. The family squabbles that have made so many headlines recently were ignored. After the funeral, as the family walked back up Chapel Hill, Prince Harry talked to his estranged brother, William, with Kate, Duchess of Cambridge, on his other side.

There were few images of the Queen, whose visage was carefully concealed by a black mask, like those worn by all of the congregation, as well as a large hat. The only break from her mourning black was her grandmother’s Richmond brooch, most famously worn in that chapel three years before at the wedding of Prince Harry to Meghan Markle. That was one of the last occasions in which Prince Philip appeared in public. Those happy times were echoed throughout the week after his death on April 9 by intimate snaps released by his family, including one of a smiling Elizabeth and Philip relaxing on a hill at Balmoral that was taken by their daughter-in-law, Sophie, in 2003.

The plainness and quietness of the fortress seemed to intensify the power of the emotion. As the empty Land Rover that would bear his coffin was slowly driven to the State Entrance of Windsor Castle, the hymn “I Vow to Thee My Country” could clearly be heard echoing across the quadrangle. Viewers watching on television could hear the tread of the slow steps of the Grenadier Guards on the gravel as they carried his coffin from the castle and onto the Land Rover that Prince Philip had specially converted to carry his coffin.

His widow entered St. George’s Chapel, and sat in her usual spot near the altar, waiting for her husband. She was alone.

His coffin was borne by eight Royal Marines into St. George’s Chapel, within the walls of the largest, oldest inhabited castle in the world. Halfway up the stairs, they stopped. Then, silence. Absolute, utter silence for a minute. No planes flying overhead, bound for Heathrow (they stopped air traffic control for six minutes to make sure), no rustling of orders of service by guests. Nothing but guns firing their salutes.

The Queen bowed her head. As did other members of Philip’s family.

It was precisely 3 p.m. Exactly as Philip has planned.

Silence.

The restrictions necessitated by the pandemic stripped the day down to its basics. The military procession in London and Windsor was replaced by an eight-minute walk from the state apartments of Windsor Castle down to St. George’s Chapel. Instead of 800 invited family, friends and dignitaries crowded into the medieval chapel, there were just 30 congregants; a full choir replaced by the individual voices of four choristers standing in the empty nave, their voices echoing through the chapel. Instead of loved ones reading Bible passages, that task was given to the Dean of Windsor and Archbishop of Canterbury. The public were not allowed inside the confines of Windsor Castle.

He was famously not one for fripperies. His pocket square was sharply pressed white linen; he wore the shoes from his marriage in 1947 for decades. He had no time for fuss: if a photographer was taking too long to get a group shot, he’d just stand up and walk away; Prince Harry said that his grandfather would end Zoom sessions by closing the lid on his laptop.

For more than six decades, Prince Philip had served as captain general of the Royal Marines. He saw combat while an officer in the Royal Navy during the Second World War. He left active duty when the health of his father-in-law, King George VI, was failing, yet his duty never ended. At the end of the funeral service, the buglers of the Royal Marines sounded “action stations,” signifying that all hands on a warship are to go to battle stations.

His deep Christian faith is evident in the service he helped create. It was a classic Anglican funeral service: the focus is not of Prince Philip; there were no eulogies, no odes to his accomplishments, but rather the it focused his hope of resurrection from the dead. “Philip is another sinner, redeemed by the grace of God. It is Philip, the servant of a monarch (not Elizabeth II), but a servant of the King of space and time,” an Anglican rector said to me.

The music played during the funeral were some of his favourites, including Benjamin Britten’s “Jubiliate in C,” which had been commissioned by Phillip for the choir of St. George’s Chapel. Another was Psalm 104, which he asked to be set to music and sung at a concert for his 75th birthday.

The public were not allowed inside the confines of Windsor Castle. In a way, that and the other public health rules meant that those who knew him the best—his family, friends, staff and military—could say goodbye as privately as possible, effectively closing the doors to the outside world, who watched on TVs and tablet screens. “Our brother Philip,” said the Dean of Windsor.

In 1885, his mother, Princess Alice of Battenberg, was born in Windsor Castle, under the careful eye of her great-grandmother, Queen Victoria. Now, 136 years later, her only son died in the same castle, with his wife and sovereign by his side. After the funeral, his coffin was lowered to the Royal Vault. Prince Philip will remain at Windsor Castle forever.