Queen Elizabeth II, 1926–2022

She wasn’t born to be Queen, but the accidental monarch transformed the job and inspired great loyalty across her realm

Britain’s Queen Elizabeth smiles as she walks during her visit to Newcastle, northern England, November 6, 2009. REUTERS/Owen Humphreys/Pool (BRITAIN ROYALS SOCIETY)

Share

1. The Enigma

“Do you call this a pitch,” asked Alan Hamilton, then the royal correspondent for The Times of London, “or a rink?” It was 2002, and he was peering from the press box in the rafters of what was then called GM Place, home of the Vancouver Canucks. He was waiting for Queen Elizabeth II to drop the royal rubber (called a puck, is it?) to start the hockey game. It was the Queen’s Golden Jubilee, marking the 50th year of her reign, and her 20th visit to Canada as monarch. There would be just two more Canadian visits, in 2005 and 2010.

She celebrated that 50th anniversary by touring some of her realms, doing queenly things: collecting bouquets, unveiling plaques, visiting businesses and hospitals, making little speeches. Then more plaques, more flowers, more visits, more waves. To top it off, on this Canadian leg, her husband, Prince Philip, was abnormally well-behaved. So, for this slightly barmy business of puck-dropping, Hamilton was deeply grateful. “We need it,” he said in a murmured aside. “I mean, 76-year-old woman [wearing] hat exits car, enters church, just doesn’t do.”

And yet, these thousands, perhaps millions, of small acts, performed ad tedium in the decades before and the years since that event are, to many, the public face of her reign. Small intangibles, and yet, cumulatively, relentlessly, inexplicably, of value. Of this she must have been painfully aware, for she soldiered on, always—well, almost always—with a smile and that wave, like a limp flag in a puff of air.

Did she chafe at such things, as her Philip sometimes did? We’ll never know.

There is much we don’t know, much we’ll never know about the substance of the almost 70-year reign of the woman born Elizabeth Alexandra Mary Windsor. She met more world leaders, knew more secrets, respected more confidences than any living person. Of the advice she offered in turn, and the events she shaped, we will never fully know.

She was an enigma from February 6, 1952, the morning her father, King George VI, died and she, at 25, became Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and of Her other Realms and Territories, Head of the Commonwealth, Defender of the Faith. Wife. Mother. Sphinx.

She could not, would not, emote in the way Diana, her late daughter-in-law, lived her brief life, publicly and out loud. It was not in Elizabeth’s breeding, nor in the job description. A distance must be maintained. It’s where the mystery and magic of monarchy—albeit a bit shopworn—stays hidden. Yet as her death has proved, she was greatly loved.

There is nothing democratic about a hereditary monarchy, but that didn’t stop her running what amounts to a perpetual campaign for the hearts and minds of her subjects. Without that loyalty, the monarchy dies. Not on her watch, thank you. Now that is left to her eldest son, Charles, thrust into the role at the moment of his mother’s death. The queen is dead, as the saying goes, long live the king.

Whether the allegiances, the respect and popular support she engendered in her 15 realms (the 16th, Barbados, became a republic in 2021) and the 54 nations of the Commonwealth will transfer as seamlessly to the son remains an open question, though he has spent a lifetime preparing for this moment.

He is already well past Britain’s retirement age, a bit worn by the years, by the burden of his legacy, by a life lived for better and often for worse in the public eye. He assuredly has his own ideas about the style and substance of his reign, but he is likely to find—as his mother before him—that change often meets resistance by the public, by the shackles of protocol and by the hidebound inner circle of courtiers and advisers and the political realities of the day.

She was acutely aware that one reigns due to an accident of birth and circumstance; it made her work all the harder to prove she was worthy of serving the public and advancing the monarchy into the modern age.

The shift is almost imperceptible from one year to the next. But over the long arc of her reign—from prime ministers Winston Churchill to Liz Truss over there, and Louis St. Laurent to Justin Trudeau over here—the prisoner of protocol loosened her style. She began paying income tax, reduced the need for bows and curtsies to tolerable levels, introduced the walkabout and expanded and democratized the social calendar at Buckingham Palace; indeed, for a fee you can tour many of the royal residences. She was humanized, rather than diminished, by the divorces and family strife she had in common with so many of her subjects. She travelled the world, outlived the Empire and championed the Commonwealth. For a woman who’s never owned a passport, it’s been quite the journey.

She kept the monarchy relevant, said her grandson William, now first in line to the throne, and no fan of the fustier bits of protocol. “The monarchy is a constantly evolving machine,” he once told the BBC. “I think it really wants to reflect society, it wants to move with the times, and it’s important it does for its own survival.”

A modest case in point: in March of 2012, Elizabeth kicked off her domestic Diamond Jubilee tour by taking the scheduled 10:15 a.m. train from St. Pancras station for a day visit to Leicester, where once an exclusive royal train would have been in order. Sharing the first-class carriage—well, she was Queen—were her husband, Philip, and William’s wife, Catherine, with whom by then the monarch displayed a comfortable informality. Kate was a symbol of the monarchy’s future, and multicultural Leicester signalled a changing Britain. By 2019, no single ethnic group in the city was a majority. The Queen, it can never be overstated, left nothing to chance.

A few weeks later, during a visit to Manchester city hall, she and Philip crashed the civil wedding of Frances and John Canning, proving this once stiff Queen is not above a bit of a giggle. The bride and groom, a hairdresser and businessman respectively, had sent a lighthearted invitation after learning the royals were to tour the city that day, but after receiving a kindly worded refusal letter from Buckingham Palace, they thought no more of it. They were stunned when the well-briefed royals strolled in after the nuptials to congratulate them by name and inquire about their forthcoming Italian honeymoon.

It was the kind of thing likely to give the royals a good chuckle as the Queen sipped her end-of-day gin and Dubonnet. You can unveil only so many damned plaques.

2. We Four

It was Elizabeth’s great good fortune to be born, on April 21, 1926, into a family oblivious to its impending fate. Although born third in line to the throne, she was never meant to be queen any more than her father, Albert, Duke of York, was meant to be king. That was the destiny of her uncle, David, Albert’s older, more socially adept brother. He was the one schooled in the role, his reputation polished to what proved to be a deceptively shallow gloss. David and Albert (Bertie to family and friends) were among six children of King George V and Queen Mary. It was, by the children’s own accounts, an unhappy upbringing by emotionally distant parents.

Albert developed a severe stutter as a child, one that only worsened under the withering criticism of his father, the king. Lilibet, as Elizabeth was called, was just six months old when her father, ground down by his impediment, began speech therapy under the unconventional guidance of Lionel Logue. Logue’s notes would later inform the Oscar-winning movie The King’s Speech, released in 2010. He described Albert during their first consultation as “a slim, quiet man, with tired eyes and all the outward symptoms of the man upon whom habitual speech defect had begun to set the sign.”

Although he had flashes of his father’s temper, Bertie was determined his children would not suffer the same unhappy childhood he did. By all available evidence, he succeeded. A window was opened into young Elizabeth and her sister Margaret’s world by the indiscretion of Marion Crawford, their Scottish governess, who lived with the family from 1933 to 1948. In 1950, to the horror of the royals, she published a book, The Little Princesses, about her experiences.

The oft-quoted anecdotes Crawford shared are of a warm, physically affectionate family—“we four,” as Bertie called them after Margaret was born in August 1930. They loved cards and charades and skits and all manner of outdoor pursuits. Elizabeth’s lifelong love of horses and her wicked gift for mimicry—something never shared in public—all stemmed from her earliest years.

The elder Elizabeth, the children’s mother, knew how much her husband had overcome to create this secure cocoon of “we four,” and yet she was worried by the anger he worked so hard to bury. She wrote her husband a private note offering parenting advice in the event of her death (though ultimately, she would outlive him by 50 years). She urged him not to shout at or “ridicule your children or laugh at them. When they say funny things it is usually quite innocent . . . Remember how your father, by shouting at you and making you feel uncomfortable, lost all your real affection. None of his sons are his friends.”

Those early years built a solid foundation for the young Elizabeth. “I think I’ve got the best mother and father in the world,” Princess Elizabeth would write her parents during her honeymoon, “and I only hope that I can bring up my children in the happy atmosphere of love and fairness, which Margaret and I have grown up in.” They lived in a rarefied world, but they had lesser royal roles. Father was a duke who would never be king. She was a princess, never to be queen. Or so it seemed.

Bertie’s brother, David, first in line to the throne, had been considered popular and effective in his role as Prince of Wales. It left him sufficient scope and time for extracurricular pursuits, including affairs with married women. His father, a few months before his death, may have realized his eldest son’s limitations. As hard as he’d been on Albert, both he and his wife saw a strength of character in him that David lacked. “I pray to God that my eldest son will never marry and have children,” he reportedly told a friend, “and that nothing will come between Bertie and Lilibet and the throne.”

The king would get his wish, posthumously, after a crisis that threatened the monarchy’s foundations. George V died on January 20, 1936. David became King Edward VIII. It is said he dissolved into hysterics at his father’s deathbed—less from grief, many suspect, than from a realization of the crushing burden that awaited.

His reign lasted less than a year. His determination to marry Wallis Simpson, a twice-divorced American and his lover for several years, was blocked at every turn, most certainly by Stanley Baldwin, prime minister of the day. Moreover, as king, he was head of the Church of England, which didn’t sanction divorce.

The likelihood of his abdication first played out behind the closed doors of cabinet and the palace. Bertie, the heir presumptive, viewed his looming fate with dread. He was painfully shy and hampered by his stammer in an era of increasingly important radio communication. He felt ill-prepared for a role he never wanted, as the drumbeats of war sounded from across the Channel in Adolf Hitler’s Germany. “David has been trained for the great position he holds and now wants to chuck away,” Albert wrote to his mother in the days before his brother’s abdication. “I am feeling very overwrought as to what may befall me, but with your help I know I shall be able to carry on.”

On December 11, 1936, in a broadcast from Windsor, Edward VIII ended the sad soap opera by announcing he had abdicated the throne. “I have found it impossible to carry the heavy burden of responsibility and to discharge my duties as king as I would wish to do without the help and support of the woman I love.” It was interpreted as a romantic act of courage by some, and an act of self-indulgence by many. “He wasn’t much of a chap, really,” said Miles Fitzalan-Howard, 17th Duke of Norfolk. “He let the side down, very much.” The abdication was no great loss in the view of Alan Lascelles, who served as assistant private secretary to George V and during his wayward son’s brief reign (he was private secretary to both George VI and Elizabeth II). “His only test of conduct was whether or not he could ‘get away with it,’” Lascelles later wrote of Edward VIII.

With the abdication, Bertie, thrust into the role of King George VI, became the latest royal conscript. He must have looked with mixed emotions at his beloved Lilibet, all of 10 years old, her future path now cast in stone. One day she would be queen—if she, unlike his brother, could endure this life sentence.

The Countess of Longford, a well-connected royal biographer, told the story of Elizabeth and her six-year-old sister, Margaret, playing in their house near Hyde Park Corner when they heard raucous cheers from a crowd nearby. Elizabeth ran downstairs to be told by a footman that her father was now king. “Does that mean you’ll be queen?” Margaret asked. “Yes, someday,” said Elizabeth. And Margaret said: “Poor you.”

It was the year of three kings, as 1936 became known. Few could have suspected then that the next monarch, little Lilibet, would go on to reign for so many years, the longest of any British monarch. Her defining characteristics—calmness, consistency, stability—may well be rooted in the turmoil of her 10th year of life.

3. A Royal Apprentice

It’s not every girl who gets her own Girl Guide pack. But the 1st Buckingham Palace Guide Company was formed for the princesses when the new king and queen moved to the palace. It was a select group of Brownies and Guides, all the daughters of aristocracy and palace staff. Guiding was a rare bit of stimulation with children her age. Her home-schooling, in retrospect, seems remarkably haphazard for a future queen. Crawford—Crawfie, as Elizabeth called her—acted as teacher and governess. Classes ran from 9:15 to 12:30 with a half-hour break. Then lunch with her parents if they were at home. Crawfie taught the basics. Additional tutors taught French, music and dance. Afternoons were largely free of study. Even by the time Elizabeth was 11, when she was next in line to the throne, Crawfie wrote: “I have been more or less commanded to keep the afternoons as free of ‘serious’ work as possible.” It left Elizabeth time for the dogs and horses that remain among the great joys of her life.

Books were another constant companion. Her mother, no deep intellectual, indulged Elizabeth’s love of light reading, once appalling Crawfie by ordering the works of P.G. Wodehouse for her daughter. The young princess favoured fiction from the past: the Brontës, Kipling, Stevenson. In later years—when not ploughing through the daily delivery of red leather boxes of documents—she leaned towards historical fiction, such as Canadian author Lawrence Hill’s The Book of Negroes, about black British Loyalists and the transatlantic slave trade, or Australian Kate Grenville’s The Secret River, about an Englishman transported to Australia for theft.

MORE: The many times the Queen graced the cover of Maclean’s

For all of Elizabeth’s freedom and lack of educational rigour, Crawfie considered her a serious student with a strong work ethic. By 13, her studies intensified. It was 1939, dark days and serious times. The girls were secretly moved from Buckingham Palace to a heavily fortified Windsor Castle, where they spent much of the remainder of the war. Twice weekly, Crawfie would accompany Elizabeth to Eton College, the exclusive boys’ boarding school down the hill from the castle. There, she received enthusiastic, if somewhat eccentric, instruction in history, the parliamentary process and Britain’s mishmash of largely unwritten constitutional traditions and precedents—knowledge that has served her well during thousands of meetings with 15 British prime ministers.

The war years provided their own education. The young princesses saw, as never before, their parents’ determination to serve by example, in little ways and bigger ones. They watched their father labouring over his wartime radio broadcasts with the help of his speech therapist. To save resources, he ordered tubs at the royal residences painted with a black line to allow just a few inches of warm water for bathing. The king and queen spent much of their time at Buckingham Palace—the target of nine German bomb attacks—while the children were in relative safety at Windsor Castle.

Their mother showed the sort of British resolve that sustained the home front during the war’s darkest days. In 1940, she famously refused to consider leaving England for a safe haven like Canada when she and the king were nearly killed after a German bomber delivered its payload on the palace. “The children will not leave unless I do,” she said. “I shall not leave unless their father does, and the king will not leave the country in any circumstances whatsoever.”

The girls lived behind blackout curtains in a gloomy, chilly Windsor Castle. “It seemed to be perpetual twilight,” recalled Margaret Rhodes, first cousin to the princesses. It became a way station for convalescing Allied soldiers, and the princesses were both the wards and hosts of the Grenadier Guards assigned to protect the royals.

The girls became accustomed to what their mother called the “whistle and scream” of some of the 300 high-explosive bombs that rained down in the area during the conflict. There were also plans “for my cousins to disappear in the event of an invasion,” Rhodes later recalled in her book, The Final Curtsey. Elite soldiers were on 24-hour call to spirit the royals in armoured vehicles to a safe house in the country if Germans stormed the island.

In these years Elizabeth overcame much of her innate shyness, grew comfortable in the company of men and developed her gift for small talk. She also learned life’s harder lessons. Some of the guardsmen the girls had befriended later died in battles overseas. Elizabeth would write notes of condolence to the families, sharing any personal reminiscences.

Her Girl Guide troop also soldiered on, its gatherings having shifted to Windsor. Elizabeth got “an unexpectedly democratic experience” when refugee girls from London’s bombed-out East End moved to the Windsor estate and joined the troop, according to Sally Bedell Smith in her biography Elizabeth the Queen. There, activities like earning cooking badges were a less genteel affair than in earlier days at Buckingham Palace. “With their cockney accents and rough ways, the refugees gave the future Queen no deference,” the author writes. They called her Lilibet, a nickname that was off-limits even to daughters of the aristocracy, “compelling her to wash dishes in an oily tub of water and clean up the charred remains of campfires.”

She had another chance to dirty her hands in the closing days of the war. In 1945, she joined the Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS), learning how to drive trucks and ambulances, as well as to bleed brakes, change oil and strip engines. It was a source of pride, with no small propaganda value, to have Elizabeth in uniform. Her incessant talk of this new mechanical prowess amused her parents no end. At one point the king put her to the test, chiding her for her inability to start a stalled vehicle, Deborah and Gerald Strober recount in The Monarchy: An Oral Biography of Elizabeth II. Later, he admitted to having removed the distributor cap as a prank.

The war in Europe ended not long afterwards. VE day, May 8, 1945, was a heady time for war-weary England. While the two young princesses had been spared much of the privation of the citizenry, they’d also endured more than their share of isolation. They watched enviously from balconies and windows at Buckingham Palace as impromptu street parties erupted below them. They begged their father to let them join the crowd and the king relented, writing in his diary that his girls had “not yet had any fun.”

A group of young people, including the princesses and some obligatory escorts and guards, slipped into the crowds. Elizabeth pulled the peaked cap of her ATS uniform down low over her eyes to shield her identity, but a Grenadier in the party objected to the improper dress, recalled Rhodes. “My cousin didn’t want to break King’s Regulations and so reluctantly she agreed to put her cap on correctly, hoping that she would not be recognized. Miraculously, she got away with it.”

They danced a conga line through the streets, sang songs, and fought their way back to the palace, joining a crowd chanting for an appearance by the king and queen, as 19-year-old Elizabeth later breathlessly recorded in her diary. They appeared on the balcony as the crowd roared its approval. “It was a view of her parents that the princesses had never before experienced,” Rhodes said. The author called it “a unique burst of personal freedom; a Cinderella moment in reverse, in which they could pretend that they were ordinary and unknown.”

The next day the family toured London’s East End and south London, both laid low by bombing raids and V-2 rockets. They saw another London, its residents grimy, ill-housed, poorly dressed and fed. And perhaps, as BBC journalist Andrew Marr writes in his perceptive The Diamond Queen, they saw the inklings of irrevocable social change—“[a] tea-drinking, cigarette-smoking, wireless-addicted people who were turning against the class-bound Britain of before the war.”

The general relief of VE day was tempered by the war with Japan, which raged until its surrender on August 14. There was one man in uniform Elizabeth desperately wanted to see safely back from harm’s way. His picture was on her bedroom mantel. Her photo was in his travelling bag. Her parents were wary. She was young, sheltered and naive. He was brash, worldly, and very much a loose cannon.

4. Enter Philip

For those who believe in love at first sight (it’s likely their paths crossed as children, but why ruin a sweet story?), Princess Elizabeth fell for Prince Philip of Greece when she was just 13 and he was a rambunctious 18-year-old naval cadet with little money and a whole lot of baggage. The royals had stepped off a yacht in Dartmouth, England, in July 1939. The two princesses needed entertaining, and Philip was conscripted from the local naval college to be their minder. His two qualifications were his royal lineage (he and Elizabeth are third cousins), and a clean bill of health from the mumps that had sidelined his fellow cadets.

He made the most of it, throwing himself into games with the girls, leaping about with abandon, wolfing back a better class of food than cadets usually warrant, even rowing a small boat after the departing royal yacht until a scowling king waved him off.

Crawfie thought him a show-off. Father wasn’t impressed. And Elizabeth, by all accounts, was smitten. “True love,” said biographer Marr, “the classic coup de foudre, is rare enough to make the queen a lucky woman.” As Graham Greene wrote in another context, “There is always one moment in childhood when the door opens and lets the future in.” This was her moment.

The Queen has always loved a bit of gossip, so no doubt she sussed out Philip’s notorious backstory after that meeting—if that wasn’t part of what attracted her to him in the first place.

His story begins in Greece, an apparent sin that aged courtiers at Buckingham Palace never got over. In fact, he hasn’t a drop of Greek blood, and his mother, Alice, was born at Windsor Castle in the presence of Queen Victoria, her great-grandmother. As for Philip, he was born in 1921 on a kitchen table on the island of Corfu, the first boy among five children. Alice, deaf since birth, was increasingly erratic, and heading for a total breakdown. His father, Prince Andrew of Greece, was a Greek army commander caught up in a losing war with Turkey. Following the defeat, and a coup, Philip’s father was sentenced to death by firing squad. A hurried intervention from Britain allowed the family to flee by boat, with Philip sleeping in an orange crate.

That was his first 18 months.

The family, with its finances left behind, was bounced among relations in Europe and Britain. Alice, having declared herself a bride of Christ, was diagnosed as schizophrenic and was sent off to a Swiss sanitorium. Years later, her equilibrium restored, she lived at Buckingham Palace, walking the halls in a nun’s habit. His four older sisters all left home within 15 months of each other to marry German princes. This didn’t sit well come the Second World War. When Philip’s detractors weren’t calling him “the Greek” behind his back, it was “the Hun.” His father also checked out, moving to Monte Carlo, taking a mistress and gambling out his days with style, if not success.

As for Philip, he lived a kind of genteel homelessness: attending boarding school, living with various rich relatives during holidays, with nary a Christmas or birthday card from his parents.

That was his first 10 years.

“He had the most awful childhood,” Hugo Vickers, author of Alice: Princess Andrew of Greece, the definitive biography of his mother, said in a 2010 interview with Maclean’s. And yet, Vickers recalled Philip being fiercely protective of his father when Vickers showed him a draft of his book. “He holds his father in very high esteem,” said Vickers. “Let me put it this way: he convinced me that he thinks his father was a good father. He hasn’t actually convinced me that he was a good father.”

That which did not kill him, only made Philip . . . Philip. Blunt. Self-reliant. Self-contained. Impatient. Also sensitive and introspective, his intimates insist, but damned unlikely to show it. “My mother was ill, my sisters were married, my father was in the south of France,” Philip told author Gyles Brandreth, dismissing his childhood. “I just had to get on with it. You do. One does.”

The Royal Navy was a natural fit for Philip. He’d had relatives who served in the Greek navy. And both his maternal grandfather and his ambitious and influential uncle and mentor, Louis Mountbatten, rose through the ranks at different times to become Britain’s first sea lord. If the young cadet Elizabeth was drawn to seemed light and exuberant, it’s because, in the navy, Philip finally had found his home.

He had barely finished his training before the war swept him off to sea. He and Elizabeth continued to correspond. Occasional home leaves were spent at Windsor, drawing him closer to a teenage Elizabeth and her family. In a letter to her mother, the queen, he thanked her for “the simple enjoyment of family pleasures and amusements and the feeling that I am welcome to share them.”

His was a good war, as the British say. He was credited with a key role in sinking two Italian cruisers. He was aboard HMS Whelp in Tokyo Bay during the surrender of Japanese forces. The Elizabeth he found on his return in March 1946 was a mature young woman of striking beauty. The two drew close. The king hoped it was a passing fancy, “as she has never met any young men of her own age.”

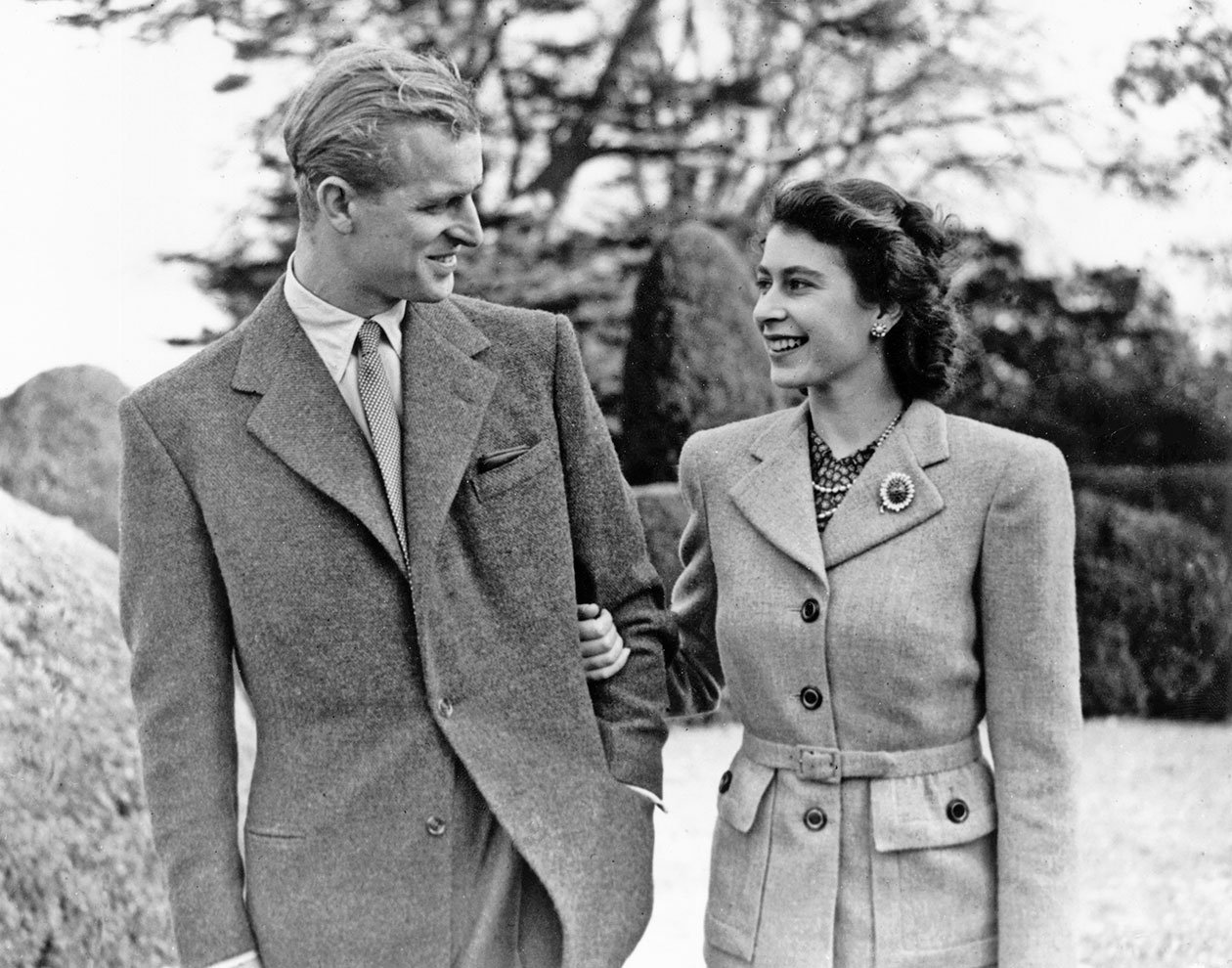

If there was an “aha!” moment that sent rumours beyond the royal circle it was a “sexy” photograph taken in October 1946, when they were both invited guests at the wedding of their mutual cousin, Lady Patricia Mountbatten, author Bedell Smith said in an interview. It catches them in the church doorway. Elizabeth, at once demure and prideful, has thrown open her fur coat, as though unwrapping a present. Philip, in his uniform, grins in approval. “They’ve never been physically demonstrative,” said Bedell Smith, “but I think from the very beginning there’s been a real physical charge between the two of them.”

In fact, they were already secretly engaged. Philip proposed that summer during a visit to the royal estate at Balmoral, Scotland. Elizabeth, all of 20, said yes instantly, without consulting her parents. The only concession they were able to wring from her was to keep the engagement under wraps until she was 21, and until the family returned from a four-month tour of South Africa.

One of the most important speeches Elizabeth has ever made came before her marriage, in a broadcast from Cape Town marking her 21st birthday. It was a simple, forthright pledge to the Empire: “I declare before you all that my whole life, whether it be long or short, shall be devoted to your service and the service of our great imperial family to which we all belong. But I shall not have strength to carry out this resolution alone unless you join in it with me . . .”

The sun was already setting on the Empire, but she knew even then that the monarchy and the evolving notion of a looser Commonwealth could endure only with the will of the people.

If her parents had any hope that time and distance might cool the ardour between her and Philip, they proved groundless. The engagement was announced on July 10, 1947. The wedding date was set for November 20 at Westminster Abbey. For Britons still clipping ration coupons in the lean aftermath of the war, the event was a welcome bit of pomp and colour.

For her parents and palace insiders who tried to steer her to safer, less complicated grooms, it was a wake-up call. Despite her fealty to God, Empire and king, there was a steely resolve to Elizabeth. Philip was neither safe nor easy. As Vickers said: “She took on someone her own size.”

Marrying Philip was the most incautious act of her young life. Perhaps her most incautious act, period.

When Queen Elizabeth II sat in Westminster Abbey for the wedding of her grandson William and his bride, Catherine, in the spring of 2011, she must have reflected on her own nuptials 64 years before. It began the most carefree time of her heavily proscribed life. She was a princess, yes, but she was also an officer’s wife, and soon, a mother to Charles in 1948.

Philip spent the first couple of years of marriage juggling new royal duties and working a desk job at the Admiralty, “pushing ships around.” In late 1948 he was posted to Malta as second-in-command of HMS Chequers in the Mediterranean fleet. Elizabeth shuttled between Malta and her royal and parenting duties in England.

As a child, Charles spent much of the time—much too much, he would later lament—separated from his parents and looked after by nannies and his doting grandparents. As callous as it sounds, it was hardly unusual in royal, or certainly military, families at the time. Elizabeth, at age one, had been left for a good part of the year while her parents toured Australia. Philip had such a dysfunctional upbringing, it must have been hard to whip up sympathy years later when a middle-aged Charles went public with his angst-filled reminiscences of a lonely childhood.

Anne was conceived in Malta and born in August 1950. A month earlier, Philip was promoted to lieutenant commander and took his first—and only—command, of the frigate HMS Magpie. During her lengthy stays in Malta, Elizabeth had a rare taste of freedom. There were dinners out and dancing at local hotels. “She was a naval wife: she went to the hairdressers; she went out for coffee, and all the rest of it,” the Countess of Longford would later recount. “It must have been great fun to have that short period.”

To Michael Parker, the former naval officer who served as aide to the couple, there was “an enchanted atmosphere” to that time, he told the Strobers. “Now, in our innocence, we thought this was going to go on for a very long time—after all, the king was quite young; there might have been 40 more years for her as princess.”

5. Too Soon the Queen

Elizabeth had one edict for Philip when she agreed to marry him: quit smoking. Her father was heavily addicted to cigarettes, and she blamed them for the toll on his health during the war years. Philip obliged, quitting cold turkey the night before the wedding.

For the king, however, the damage was done. In 1949, plagued by arteriosclerosis, he underwent surgery to aid the circulation in his legs. A greater burden of his duties fell to Elizabeth. It became apparent that Philip had to surrender his command and return to London. In 1951, surgeons operating under palace chandeliers removed the king’s cancerous left lung, though the severity of his illness was kept from the public.

Back in public life again, Elizabeth and Philip became as glamorous in their day as William and Catherine are now. It was something neither of them particularly sought. Philip treated celebrity as radioactive: unstable, fickle and probably more harmful than helpful. “Safer not to be too popular,” he said. “You can’t fall too far.” His dim view was confirmed for him years later as son Charles and his wife, Diana, were consumed by the media during their marital meltdown.

In the autumn of 1951, travelling in the king’s stead, Elizabeth and Philip undertook their first major international tour—to Canada and the U.S.

Canada, it seems, is a royal rite of passage for the Windsors. Elizabeth II visited 23 times, 22 of them as Queen. It was the first stop in 2011 for William and Kate, the newly minted Duke and Duchess of Cambridge. William, in his farewell address in Calgary, recalled an even earlier generation. “In 1939, my great-grandmother, Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother, said of her first tour of Canada with her husband, King George VI, ‘Canada made us.’ ”

If you can make it here, apparently, you can make it anywhere. That said, the 1951 tour proved a grueling apprenticeship for Elizabeth and Philip. Fearful for the king’s fragile health, the couple and their entourage elected to make their first transatlantic flight rather than taking an ocean liner. What followed was a 35-day trek across the country and back in a 10-car royal train.

It was a schedule that would have put the king in his grave: 70 stops, including one epic day in Ontario in which they visited eight communities. They rode through Winnipeg in a convertible equipped with a plastic bubble to shelter them from the cold. In Calgary, they shivered under Hudson’s Bay blankets watching a rodeo, Philip quite taken with his gift of a 10-gallon hat. Sixty years later, William and Catherine, in cowboy duds, replicated the Calgary experience in more sensible weather.

For Elizabeth and Philip, the weeks of travel and the relentless public spotlight took a toll. Philip was still making an adjustment from ship commander to second fiddle. There were flashes, for better and worse, of the consort he would become. He did provide welcome comic relief, able to loosen up the crowd with cheerful asides and seek out the children while Elizabeth steamed ahead, powering through an agenda that was overstuffed with VIPs.

Privately, on the train, Philip tried to keep the mood light, but he chafed at the influence that stuffy palace courtiers held over his impressionable young wife. Martin Charteris, new to what would be a 30-year role as a senior adviser to Elizabeth, said Philip resented the constant, often disapproving presence of the courtiers. “He didn’t like that. If he called her a ‘bloody fool’ now and again, it was just his way. I think others would have found it more shocking than she did.”

Philip was also taken aback when one of his offhand remarks about Canada being “a good investment” raised the hackles of editorialists who considered it a condescending example of British imperialism. This, of course, didn’t stop him from making many more so-called gaffes along royalty’s rocky road. The evidence suggests that Elizabeth—whose every public utterance seems run through an internal editor to wring out all spontaneity and controversy—wasn’t overly concerned by this. One of Philip’s unsung roles may well have been as her pressure release valve, saying the things she couldn’t. She was the china shop; he was the bull.

As for Elizabeth, she was stung when the avalanche of favourable Canadian press also included the wish that she might cheer up. Part of this was worry for her ailing father (her aides had packed black mourning clothes and the documents required for her accession—just in case). But she has lamented that in repose, she doesn’t have a “smiley face,” as she put it. Her default is a serious mien, somewhere between a frown and a case of indigestion. “My face is aching with smiling,” she complained to Charteris during the tour.

Her aching face on that Canadian tour was a lesson learned. Sincerity is for others to fake. She was neither an actress nor a politician, nor should she be. She laughed and smiled when there was a genuine reason to do so. A telling example of her distaste for false enthusiasm came later as Queen, during an official visit to Hull, a city in Yorkshire then in post-industrial decline. Her speechwriter had written: “I’m very pleased to be in Hull.” She crossed out the adverb, telling the assembled: “I’m pleased to be in Hull.” In the Queen’s view, the road to Hull was paved with good intentions, not great ones.

Still, the Canadian tour—and a side visit to the U.S., where president Harry Truman called her a “fairy princess”—was deemed a great success. In many respects, it “made” the princess, as much as the 1939 trip made her mother, or the 2011 honeymoon tour of William and Catherine renewed the franchise.

The couple’s return to England after a month away from their children underscored a dilemma Elizabeth has faced, with mixed results, for much of her reign: the work-life balance every parent struggles with. In her case, raised to revere protocol and understatement, the scales tipped in favour of her all-consuming vow of duty to the Empire, especially in those early years.

Biographer Bedell Smith described their arrival at London’s Euston Station after the Canadian tour, three days after missing Charles’s third birthday. “Elizabeth rushed to hug her mother and kiss her on both cheeks. For tiny Charles, she simply leaned down and gave him a peck on the top of his head before turning to kiss Margaret. ‘Britain’s heiress presumptive puts her duty first,’ explained a newsreel announcer. ‘Motherly love must await the privacy of Clarence House.’ ” Really? Even in those buttoned-down times, surely, the monarchy could have survived a motherly hug and kiss.

At least two people on the platform that day—Charles and Elizabeth’s sister, Margaret—would find their lives irrevocably altered for the worse by Elizabeth’s perceived need to put duty first.

In the new year of 1952, with the king in dangerous decline, Elizabeth and Philip packed again for a six-month tour—of Australia, New Zealand and Ceylon. They tacked on several extra days at the front end to visit a game reserve in Kenya, then a British colony. She and Philip stayed in a cabin built in a huge fig tree, watching and filming a parade of wildlife trundling below.

Just days into the trip the king, aged 56, died in his sleep. The news of his death was relayed to Michael Parker in Kenya on the morning of February 6. He awoke Philip from a nap. “His first reaction was almost as though a huge wave had hit him,” Parker recalled. “First of all, there was his complete concern for her as a human being, and secondly, the implications of the fact that she was becoming the Queen and he is her husband.”

The staff arranged an emergency flight home. Philip broke the news to his wife. He put his arm around a weeping Elizabeth and they walked up and down the lawn, contemplating their loss and the daunting new reality. His naval career was over. She was queen. He was her consort; their life sentence had begun.

6. On the Job

By June 2, 1953—coronation day—Britain had long since lifted itself out of grief over George VI’s death. The public was eager, despite the dismal wet weather, to celebrate their new Queen. By coincidence, two other heroes were crowned that day, with news that New Zealander Edmund Hillary and Nepalese guide Tenzing Norgay had reached the summit of Mount Everest. The Empire was in decline, but in the Commonwealth all seemed possible.

The coronation was a glittering affair, although encumbered by the weight of liturgy, ancient tradition and all those jewels. Little Charles, at four, looked supremely bored. The Queen wore her serious face. The event was recorded by some 2,000 journalists from 92 countries.

Back in December, the Queen had decreed that television cameras could broadcast the event in Westminster Abbey. Both the dean of the abbey and then-prime minister Churchill had been opposed, fearing it would debase the monarchy by bringing the ritual into the home of any beer-swilling everyman who cared to watch. For Churchill, who had a close personal relationship with alcohol, this embrace of tradition seems a bit over the top.

Elizabeth’s determination to prevail against such powerful forces was a display of her determination to push the monarchy, however slowly, into the modern age. “I have to be seen,” she has said, “to be believed.”

You would think that being a Queen and a duke, you pretty much get to do what you want. You might be surprised to realize that’s not the case. Certainly, Philip was. Although William obviously wasn’t around in the early days of her reign, he perceptively captured their dilemma in an interview with author Robert Hardman. Of his granny, he said: “Back then, there was a very different attitude to women. Being a young lady at 25 and stepping into a job that many men thought they could probably do better must have been very daunting. And I think there was extra pressure for her to perform.” Of his grandfather: “The Queen was taking on her role in a man’s world; the Duke of Edinburgh was taking on the role of a consort as a very successful naval commander.”

So, in that understated, underhanded, Shakespearean sort of way there was genteel butting of heads inside the palace walls. The Queen, scarred by her uncle’s abdication, placed much value on continuity. As often as not, then, she took the easier path of girding herself in the stuffy rules of protocol foisted on her by what biographer Carolly Erickson called “the same tightly knit meticulously self-regulating group of senior household officials that had advised her father.”

Philip had, in some respects, the tougher time of it. What actually does a consort do, apart from a somewhat useful role in the production of heirs? Philip’s job, plain and simple, or not so simple, was to support the Queen.

One obvious way is by being there. The Queen did not make an official foreign trip in all her reign without Philip. They were enthusiastic dancers in their younger years and you see their synchronicity on the thousands of walkabouts they’ve done—an innovation she introduced only in 1970. They frequently worked different sides of the street. Philip often played spotter, hoisting a small child with a bouquet over the security fence, or searching out a war veteran for the Queen to meet. It was fascinating watching William and Catherine on their first Canadian tour working different sides of the path with a similar rhythm. Clearly, they learned from the best.

Elizabeth ceded to Philip the job of running the estates and much of the raising and educating of the children. He took on tasks like modernizing Buckingham Palace, adding dishwashers and other labour-saving devices that require electricity. In this, as with many things, he ran into stiff resistance from the old guard.

By the end of his life, the estates where he held the most sway—Balmoral in Scotland, Windsor and Sandringham—were tidy, innovative money spinners. Even at 90 he was thinking long-term, planting a vineyard at Windsor and a truffle farm at Sandringham. He took his campaign for productivity well beyond the palace gates, railing in speeches in the 1960s that British industry was desperately short of innovation and efficiency. “Gentlemen,” he said, “I think it’s time we pulled our figures out.”

In this, he had a freer hand than his wife, who could only signal her approval by choosing which factories to visit. His belief in mental and physical rigour led to his founding the Duke of Edinburgh’s Award for young people who perform community service and meet a demanding series of physical challenges. In its early days, as author Vickers told Maclean’s, courtiers dismissed it as akin to Hitler Youth. Today it is a recognized gold standard on a recipient’s CV, one that opens doors to better schools and jobs. As in most things he sets his mind to, the duke prevailed.

7. Married, with Children

From the outside, it’s near impossible to assess the state of any marriage, and this is especially true of Queen and consort. Still, there are enticing glimpses that suggest it has its spirited moments. Patricia Mountbatten, a one-time lady-in-waiting to her cousin the Queen, recalled getting into a “right old ding dong” with Philip over some aspect of policy with South Africa. “It was a terrific argument and the Queen kept encouraging me. ‘That’s right, Patricia,’ she’d said, ‘You go at him. Nobody ever goes at him.’ ”

She also took a road trip with the couple, with Philip, as usual, driving with reckless abandon. Elizabeth repeatedly sucked in her breath in alarm and disapproval. “If you do that once more,” Philip snapped, “I shall put you out of the car.” Mountbatten asked the chastened Queen why she put up with such comments. Because, she replied, “I don’t want to have to walk back.”

That said, Elizabeth is no shrinking violet. She’s quite capable of wringing a wounded pheasant’s neck during a family shoot, or telling Philip, “Oh, do shut up.” A case in point: a donnybrook between the two in Australia in March 1954, during a daunting six-month post-coronation world tour.

They were staying at the O’Shannassy Reservoir in Victoria, where they were to meet a crew filming a documentary called The Queen in Australia, author Hardman recounts in delicious detail in Our Queen. The couple were late. Cameramen Loch Townsend and Frank Bagnall, waiting impatiently outside their chalet, soon found out why. “Out dashed Prince Philip, with a pair of tennis shoes and a tennis racquet flying after him. Next came the Queen herself, shouting at the Prince to stop running and ordering him back,” Hardman wrote. She dragged Philip back inside, and the door was slammed.

A gobsmacked Bagnall, acting on instinct, had his camera running. Moments later, Richard Colville, the Queen’s pit bull of a press secretary, stormed out, raging at the crew for filming the event. Townsend, who bravely filmed combat during the Second World War, wilted before the onslaught of the man the British press called “the Abominable No Man” for his ferocious control of the Queen’s image. To the amazement of a protesting Bagnall, Townsend opened the camera exposing the film. “You may have finished using your balls,” he told Bagnall, “but I’ve still got work for mine.”

Townsend gave the now-useless film to Colville as a peace offering. Shortly afterwards the Queen emerged, grateful, and serene, he recounted years later to a historian. “I’m sorry for that little interlude, but as you know, it happens in every marriage,” Townsend recalled her saying. “Now,” she asked him, the matter behind her, “what would you like me to do?”

Still, most royalty watchers regard the marriage as an enduring love match or at least an effective partnership. “It’s not extraordinary,” Canadian Garry Toffoli, co-author of Queen and Consort, said of their more than six decades of teamwork. “It’s a reflection of the ordinary carried on in extraordinary circumstances.”

In any event, divorce was never an option for Elizabeth. She made her feeling on that clear in a 1949 speech to the Mothers’ Union rally, in which she railed against divorce and “the age of growing self-indulgence, of hardening materialism and of falling moral standards.”

That six-month Commonwealth tour was one of many times the children were left behind over the years. The first two, Charles and Anne, had it the roughest. Royal voyages were longer then, and Elizabeth was literally and metaphorically at sea as she coped with the new demands of the job, then her father’s death and the responsibilities of taking over the firm, and living over the shop at Buckingham Palace. By the time the second set of children arrived—Andrew in 1960 and Edward in 1964, she had more experience as Queen and a greater inclination to engage as a mother. “Goodness, what fun it is to have a baby in the house again!” she said after Edward’s birth.

Anne, a gifted equestrian, always shared a love of horses with her mother. She also had her father’s thick skin, forthright nature and deep pool of self-confidence. It allowed her to move unscathed through the travails of childhood and boarding school. In 1974, she showed her grit in rebuffing an armed kidnapper who blocked her Rolls-Royce on the Mall near the palace, shooting her chauffeur, a policeman and a passerby. When he tried to pull Anne from the car, she snapped, “Not bloody likely!” And, with the help of her then-husband, she resisted until reinforcements arrived.

Charles took less well to parental absences, to boarding school life, and to his father’s brusque impatience. Philip called himself a pragmatist, and his eldest son, “a romantic.” In fact, they have much in common: a regard for farming and poetry, a fascination with science and the environment, a love of painting—Philip in oils and Charles in watercolours.

Oil and water has indeed defined their relations at times. The low point was in 1994, when Charles, his marriage to Diana in shambles, collaborated with his friend and journalist Jonathan Dimbleby in a revealing biography. He admitted to a lonely childhood and an emotional estrangement from his parents. While Charles was too proud to admit it, Dimbleby wrote, “The Prince still craved the affection and appreciation that his father—and his mother—seemed unable or unwilling to proffer.”

Whether the Queen could have done more to ease Charles’s melancholy is an open debate among her biographers. Elizabeth biographer Marr believes both were products of their environment. Charles was “simply very different” and ill-suited to the sacrifices his mother felt compelled to make. The dedication she made to public service on her 21st birthday was “the speech of a true believer—in monarchy, nationhood, God and destiny—which left little time for an ordinary relaxed family life.”

The Queen’s sister, Margaret, also paid a price for Elizabeth’s fealty to God and country. Margaret was 22 when she confided to her sister she wanted to marry Peter Townsend, a divorced RAF war hero who had served as the king’s equerry. The church, the cabinet and Churchill, the prime minister, were dead set against a divorced man marrying into the royal family. The Queen, caught between sister and state, did little or nothing to advance her sister’s case.

The relationship collapsed, as did a subsequent marriage and a sad string of Margaret’s other relationships. Despite her heartbreak, the sisters remained close. Margaret, a heavy smoker and drinker, died in 2002, having lived long enough to see Elizabeth endure the divorces of three of her own four children.

The Queen’s views would change with evolving societal norms. While Elizabeth, as defender of the faith of the Church of England, didn’t attend the 2005 civil marriage of Prince Charles to his long-time love, the divorced Camilla Parker Bowles, she gave their marriage her seal of approval by toasting the newlyweds at their reception.

In 2020, her grandson, Prince Harry, decided to leave his role as a senior working royal and move to California with his American-born wife, Meghan, Duchess of Sussex, and their young child, Archie. Though they did what she would never do—put their personal happiness ahead of royal duty—she made it explicitly clear that the couple’s wish for a more private life wouldn’t affect her affection for the Sussexes, saying, “Harry, Meghan and Archie will always be much loved members of my family.”

8. Trusted Adviser

Once a week, traditionally Tuesday afternoon around 6 p.m., the British prime minister of the day arrived at Buckingham Palace for what some have come to view as a weekly therapy session: a private meeting with the Queen. No aides were present. No notes were taken. Nothing left the room. The Queen reigned; she did not rule. But by convention she had the right to be consulted, to advise and to warn. It’s a role she took seriously. Over the years, prime ministers have discussed crises of every sort, shared cabinet squabbles, indiscreet gossip, their doubts and fears. In the Queen they got the sanctity of the confessional, a sympathetic, if non-partisan, ear and an extraordinarily well-briefed woman who knew most every state secret of the past six decades and the rogues and players behind them.

She’s never been one for confrontation or gratuitous advice. Usually she asks questions. And if the answers are lacking, she’ll ask more questions, until a PM gets the message that a particular course of action might need rethinking.

If that sounds vague, it’s because there has never been a leak of any substance of these discussions. Ever. That alone is invaluable to prime ministers. Sir Gus O’Donnell, a cabinet secretary working with David Cameron and his two predecessors, told Andrew Marr the Queen offers “a safe space” where PMs discuss things they can’t with anyone else. “They go out of their way not to miss it,” he said of the meetings. “They come out of them better than they went in, let’s put it that way.”

Well, Theresa May, prime minister from 2016-2019, may be the exception. May has gone far politically with a reputation of holding her cards close to her vest, but her refusal to tip her hand apparently didn’t sit well with the Queen and Philip during a two-day visit to their Balmoral estate in September 2016, two months after she was acclaimed prime minister. A source told the Times that the Queen was “disappointed” that May shared no plans or insight into her strategy for the key issue of the day or for the years to come—negotiating an exit from the European Union. That one-word assessment—never confirmed by palace spokesmen—was enough for the opposition to raise doubts about whether May was hiding an exit strategy—or the lack of one.

If the reports are true, May lost the benefit of one of the best-briefed people on the planet. Each day except Christmas and Easter, the Queen takes delivery of red leather boxes containing cabinet minutes, intelligence reports and issues of importance from her realms. She is known as Reader No. 1, and that is another role she takes terribly seriously. Even during official visits, such as her last tour of Canada in 2010, time is allocated for the boxes with their hidden intrigues and dense bureaucratic prose.

She has built over the years an unrivalled institutional memory. Some of it comes from papers and briefings, much of it from relationships forged in extensive travel. When William returned from the 2011 Canada tour, and no doubt his other travels, one of his first tasks was to brief the Queen. She knows Canada inside out, as successive prime ministers have discovered.

Lester B. Pearson, the diplomat turned prime minister, knew Elizabeth as a princess, meeting her as a girl when he paid his respects to her father the king while he was minister of foreign affairs. “The Queen was interested in our foreign policy and, especially, the Commonwealth, which was her major interest,” recalled Geoffrey Pearson, his son, as quoted in the Stobers’ biography of the Queen. Pearson had a role in the creation of Zimbabwe from the colony of Rhodesia. “Obviously there were a lot of common interests in questions about the future of the Commonwealth,” Pearson said. “Could it act as a bridge between East and West? Could the Commonwealth be a force for good?”

In former prime minister Brian Mulroney’s experience, the Queen is a subtle but effective force in the often-complex affairs of the loose collective of Commonwealth countries, which represent almost a third of the world’s population. “She sees herself fused into that instrument that was originally an empire,” Mulroney told author Bedell Smith.

He recalled a 1985 meeting of Commonwealth leaders in Nassau. British PM Margaret Thatcher was opposing strong support from other nations for tough sanctions against South Africa and its apartheid policy. The Queen, typically, offered no opinion about sanctions but she urged Mulroney to work with other leaders to find a unified position in their efforts to end apartheid.

At a dinner the next year she led leaders through a discussion on human rights, siding with the pro-sanction position, if one read her “nuances and body language,” Mulroney said. Ultimately, Thatcher dropped most of her opposition. “What saved the day,” Mulroney said, “was that Margaret was aware Her Majesty certainly wanted some kind of resolution.”

Most notably, the Queen and the monarchy have learned to lose gracefully when the occasion calls for it. The noses of the British establishment were disjointed by Pierre Trudeau’s plan in 1980 to patriate the British North America Act from Britain and create a Canadian-controlled Constitution. Many suspected Trudeau was a closet republican, what with his French-Canadian heritage and such stunts as pirouetting behind the Queen.

Nor did they know what to make of the rough-hewn Jean Chrétien, who, as justice minister, was Trudeau’s political fixer on the issue. The Queen and Chrétien, however, shared a mutual affection. As for Trudeau, he wrote in his memoirs, she favoured his plan. “I was always impressed not only by the grace she displayed in public at all times,” he wrote, “but by the wisdom she showed in private conversation.”

Philosophically, Canada’s assertiveness was a coming-of-age story that the Queen has seen played out in other realms. Much better to surrender a power that was largely theoretical than to lose the influence and public support that are the real glue of today’s monarchy.

In November 2015, newly elected Prime Minister Justin Trudeau met the Queen at Buckingham Palace. “Nice to see you again . . . but under different circumstances,” she said, a reference to his childhood audience at the side of his father, the prime minister. “I will say you were much taller than me the last time we met,” he replied. Days later, Trudeau delivered the toast to the Queen at the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in Malta, on her last foreign trip, saying with no exaggeration she had “seen more of Canada than most Canadians.” She thanked the 43-year-old Trudeau “for making me feel so old.”

It’s likely that Canada’s Queen had had no bigger prime ministerial fan than Trudeau’s predecessor, Stephen Harper. Meeting her first as opposition leader in 2002, he recalled being “impressed beyond description at how well [she] is informed about everything.” As prime minister, he was a near-constant presence during her 2010 Canadian tour. He ordered her portraits installed in all Canadian consular buildings abroad. He restored “royal” to the title of our navy and air force. It’s telling there was little backlash to his royal restoration efforts. Like all but the oldest Canadians, she was the only monarch he’d ever known.

Through staying power alone, she ground down republican sentiment, or at least postponed debate for another day.

9. Diana

To be in London in the first week of September 1997 was to witness a city, and a country, descending into a kind of collective mania. Diana, Princess of Wales had been killed early Sunday, August 31, in the crash of a speeding car in Paris, along with her lover of recent weeks, Dodi Fayed. The public had long since considered Diana their property. They celebrated at her marriage as a virgin bride to Charles in 1981, shared the joy of the births of sons William and Harry, and gorged themselves on the tabloid fodder of their marital breakdown and divorce some 15 years later. With her death there was an escalating spiral of grief, a search for higher meaning and a need to assign blame.

News of her death broke with her sons William, then 15, and Harry, 12, at Balmoral in Scotland. They dutifully attended church that morning, then the Queen sheltered them from view and away from the torrent of tears that was London.

In the capital, it seemed every woman wore black. Diana’s friend Elton John recast an old hit into Goodbye England’s Rose. The domestic supply of flowers was quickly exhausted as mountains of bouquets were heaped waist deep at the gates of palaces across the city. Ridiculous conspiracy theories were hatched about a palace hit on the scene-stealing Diana.

Far more dangerous to the palace, though, was the growing anger at the Queen’s silence and the princes’ absence. “Your people are suffering,” lectured the tabloid Mirror that Thursday, “SPEAK TO US MA’AM.” Editorialists lambasted her for not flying the Union Jack at half-mast at Buckingham Palace. The pole stood bare—as protocol dictates when the monarch isn’t in residence. For days she stubbornly—and foolishly, even close allies agree—refused to bend the rule, relenting only when it snapped under the weight of public outrage.

Equally worrying for monarchists was the shift of allegiances. The public so identified with the “People’s Princess” that they projected on her their own sorrows and loss. Bill Lowe, a Canadian student studying law in Wales, draped a Canadian flag across a crowd barrier nearby on the Mall, thinking of the death of his own mother when he was about William’s age. Unlike so many, he didn’t fault the Queen for allowing her grandsons to grieve privately. The British public needs to understand that the boys, he said, “are part of a family that’s been broken.”

In that, Lowe captured the Queen’s dilemma. She had chosen to act as a grandmother first and a monarch second. It was a rare reversal of her priorities, and she paid dearly for it. In more rational times, it would have been seen as the right and compassionate choice, as well as one that protected a future king.

By Friday, the day before the funeral, the boys were back in London. They mingled with the crowd at Kensington Palace, where Diana kept an apartment, accepting bouquets and condolences. Charles hovered protectively nearby, extracting them from the more uncomfortable conversations.

That evening, a black-clad Queen made her first live broadcast in 38 years. It was a note-perfect three-minute window into a family’s grief. She did not apologize, but she explained the need “to help William and Harry come to terms with the devastating loss that they and the rest of us have suffered.” She acknowledged the loss of “an exceptionally gifted human being” without resorting to hollow sentiment. “We are all trying in our different ways to cope,” she said.

Her talk calmed emotions and allowed the funeral to take its course with a greater measure of dignity and calm. Philip took the shattered young princes under his wing. They questioned if they could make the long public walk behind her coffin to the funeral, said Gyles Brandreth in Philip and Elizabeth: Portrait of a Royal Marriage. Fearing the boys would later regret avoiding that duty, Philip asked, “If I walk, will you walk with me?” And so they did.

In fairness, nothing in the experience of Queen and consort prepared them for the emotional tsunami resulting from Diana’s tragic death. They must have thought back to the death of King George VI, the Queen’s father, 45 years earlier. True, back then weeping crowds also lined the streets and crowded the palace gates, but the grief, by most reports, was more subdued, without unanswered questions, recriminations and unfocused anger. It was a different time and circumstance, not the violent end of a young mother, but the death in his sleep of a frail 56-year-old.

The mood was eloquently captured in a broadcast by then-prime minister Churchill: “When the death of the King was announced to us yesterday morning there struck a deep and solemn note in our lives, which as it resounded far and wide, stilled the clatter and traffic of 20th-century life in many lands, and made countless millions of human beings pause and look around them . . . Mortal existence presented itself to so many at the same moment in its serenity and in its sorrow, in its splendour and in its pain, in its fortitude and in its suffering.”

10. Britain’s Greatest Asset

And now she, too, is gone. And the tributes pour in. Flowers are plucked, tears flow and, yes, a “deep and solemn note” is struck in the lives of the many millions she has touched during her reign. Perhaps there will even be, as Churchill said of her father, a stilling of the “clatter and traffic” of modern life and an opportunity to reflect on the enduring legacy of this gilded conscript, so famous and yet so unknowable.

She gave a life of service but shared so little of her thoughts and feelings. Does one measure such a life in bouquets gathered, in ribbons cut, in platitudes delivered?

There has to be more, and of course there is.

There are the more than 600 charities of which she was patron, and thousands more championed by her royal brood. One of her great duties was the fostering of public service.

There was her role as the head of the Commonwealth, a separate duty from that of constitutional monarch and one that allowed her greater latitude to meet its leaders, offer advice and shape its outcomes. To the Queen it was never a frail relic of a lost empire, but a force for good, an opportunity to promote, with mixed success, democracy, human rights, and economic and social development among its member nations. Though its relevance is often questioned, there are worse things to aspire to. Would this loose collective of rich and poor, big and small, democratic and autocratic, have survived without her? Doubtful. No wonder that she was visibly pleased when Commonwealth leaders voted in 2018 that Charles succeed her as head of the organization upon her death.

As Queen, she was Britain’s greatest asset. It’s no coincidence that, at age 89, she was dispatched to Berlin in June 2015 at a time when then-prime minister David Cameron was desperate to win concessions from the European Union to bolster the remain side in a forthcoming vote on an exit from the EU. Those talks, and the remain side, failed spectacularly, but the Queen’s visit—her 270th foreign trip, her fifth to Germany, and one of her last—was a success by any measure. The coverage by the German media was fawning. There were fond remembrances that it was Elizabeth who made, at some personal cost, the first postwar overtures to Germany, legitimizing the need to normalize relations with a former enemy.

Her meeting with Chancellor Angela Merkel in 2015 was quiet diplomacy at its finest, a case of the gloved hand of influence shaking that of the most powerful woman in Europe: a Queen who lived through a war, a chancellor who endured its ugly aftermath. They could have been enemies. Instead they shared a pot of tea and a private chat—a small act of civility that could, if only one listened, speak louder than empty speeches and rattling sabres.

Consider her Christmas message in 2016. One can’t but think when she wrote this she was looking back at her 25-year-old self, heartbroken and apprehensive at the death of her father:

“When people face a challenge they sometimes talk about taking a deep breath to find courage or strength. In fact, the word ‘inspire’ literally means ‘to breathe in.’ But even with the inspiration of others, it’s understandable that we sometimes think the world’s problems are so big that we can do little to help.

“On our own we cannot end wars or wipe out injustice, but the cumulative impact of small acts of goodness can be bigger than we imagine.”

And so she did her bit, travelled the world, meeting the great and the powerful, and everyday folk beyond counting. She unveiled their plaques, awarded their good deeds and gathered their flowers. Even as her hair turned from grey to white, she showed no sign of slowing down, regularly knocking off nearly 300 engagements annually while in her 90s.

In April 2020, millions watched the Queen talk to Britain, the Commonwealth and the world, reeling from the deadly impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, in only the fourth such special video address of her reign: “While we have faced challenges before, this one is different. This time we join with all nations across the globe in a common endeavour, using the great advances of science and our instinctive compassion to heal. We will succeed—and that success will belong to every one of us. We should take comfort that while we may have more still to endure, better days will return: we will be with our friends again; we will be with our families again; we will meet again.” The broadcast was filmed at Windsor Castle, where the monarch and her husband had retreated, ensconced within a virus-free zone nicknamed the HMS Bubble.

She adapted to the twin realities of pandemic precautions and her advancing years by using video and the phone for routine engagements, such as meetings with diplomats and politicians. She began carrying a cane for balance. And, especially after the death of Philip, 99, on April 9, 2021, her family took to accompanying her at events, as her husband had done for decades. Still, a regal surge of public appearances in October 2021 proved too much, and her doctors ordered her to rest.

And, yes, this was all after she dropped the puck in a Vancouver arena on an October Sunday in 2002—an event, believe it or not, that took months of behind-the-scenes bilateral negotiation and planning.

The machinery of the monarchy moves incrementally, its sticky gears and levels resistant to change. That is both blessing and curse in a rapid-fire world, and yet it grinds on, capable of generating both grand spectacles—weddings, jubilees, funerals—and the million tiny things that fill the scrapbooks of the public imagination.

A photo montage of that puck drop held pride of place in the Parliament Hill office of Kevin MacLeod, Canadian secretary to the Queen from 2009-2017. The Queen’s face beamed with the satisfaction of a little thing done well—an act that celebrated “the country’s established religion,” as Hamilton of the Times would write.

“We were pushing the portfolio,” MacLeod said fondly of the event. “Pushing the envelope a bit, but not much.”

In many respects, that was Elizabeth, in her long journey from young princess to the world’s current longest-serving monarch: pushing the margins, not much, but relentlessly. Enough to effect change. Enough to win you over.

“Small things,” as she said, “done with great love.”

Ken MacQueen is a former senior writer for Maclean’s. Patricia Treble is a former researcher for Maclean’s and author at Write Royalty.