An impossible job: What it’s like to work in a pediatric ICU

“No child should be denied a ventilator or bed, yet these are the kinds of decisions we were having to make”

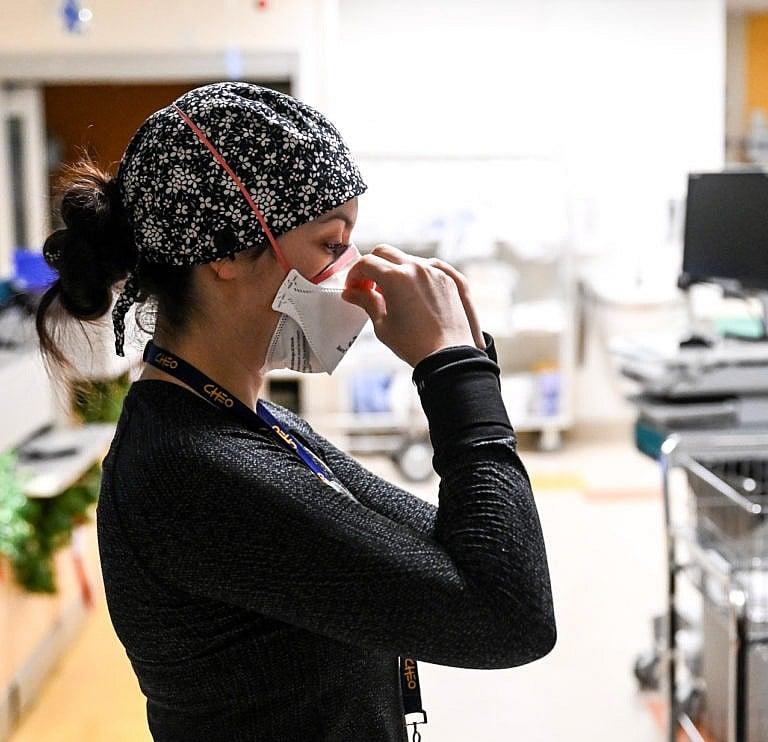

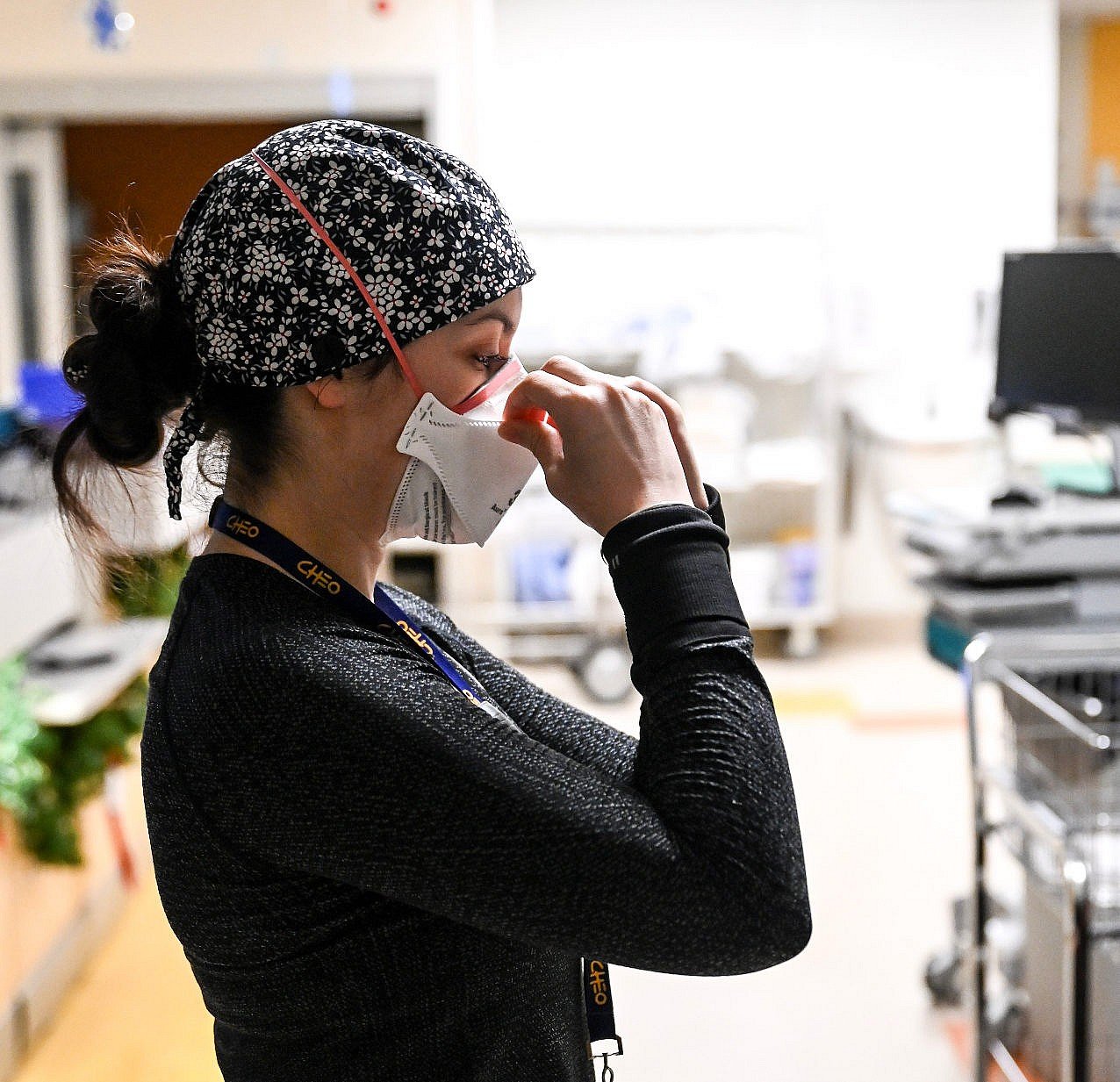

“You’re expected to deal with all this trauma, but you’re not given the tools to cope with it,” says Ottawa PICU nurse Chelsea Cadieux (Photography by Rebecca Hay)

Share

When Rebecca Hay was a teenager in Calgary, her father gave her his 2007 Canon Rebel camera and taught her everything he knew about photography. She took photos of the people she saw and the places she went, and fell in love with the art form, fascinated by its ability to help her see the world from different perspectives.

After moving to Ottawa to attend university, Hay began working as a wedding photographer on the side to help pay her tuition. She contributed to a travel photography book on the city and shot portraits in her spare time. But photography was a hobby, not a career: after graduating university, Hay returned to Calgary to attend medical school.

In 2019, during her first year of residency in pediatrics, she was required to work about seven 26-hour shifts per month, along with regular day shifts, all of which left her with little time for rest or photography. She was exhausted, sleep-deprived and constantly on her feet. During rare moments of quiet in the hospital, Hay brought her camera to work. She sat down with friends and colleagues to photograph them and hear about their experiences in health care, sharing their stories on Instagram as part of a series called “26 hr.” It gave her a chance to talk to co-workers about what they were seeing in hospitals, and to share those stories with a wider audience.

READ: Thousands of patients. No help. Meet the lone family doctor of Verona, Ontario.

In November of 2020, during an interview with pediatric resident Caitlin Marchak, the series took on a different meaning for Hay. After caring for her patients and seeing them on their worst days, Marchak said, she left the hospital feeling burnt out with little left to give to friends, family or herself. It was a feeling Hay had long struggled with herself but never talked about openly. “I knew then that I wanted to keep sharing these stories,” says Hay. “If someone could feel less alone because of them, then that would be worth it.”

Hay now lives in Ottawa, where she works as a fellow in pediatric critical care at the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, or CHEO. She continues to document her colleagues’ experiences, including in a miniseries titled “Invisible Pandemic,” which is about the pediatric crisis in hospitals caused by the surge in respiratory viruses this past fall and early winter.

We spoke to some of the health-care workers Hay has photographed.

Janet Morrison, PICU charge nurse, Ottawa

“For a few months this past fall and early winter, we went from caring for seven patients to 20. We’re only staffed to take care of seven. It was chaos. We overflowed into a second ICU, opened a third, and eventually transferred patients from our ICU to other hospitals. We were constantly waiting for free beds to admit people who needed care and had been waiting in emergency for 24 hours or longer. I worried that I wasn’t supporting my staff the way I should. It was such a busy few months. We’re coming out of it now, but we still don’t have enough nurses to care for the seven patients we’re responsible for. I think you have to be a little bit crazy to work in the ICU. There are easier jobs, but there are none more rewarding.”

Gunjan Mhapankar, pediatric resident, Ottawa

“The surge of pediatric flu, RSV and COVID-19 cases tested the limits of our emergency room and the entire pediatric public health-care system. It also affected our mental health. It seemed like the rest of the world had moved on from the pandemic, but we were in this chaotic situation with more hospitalizations and fewer beds than in the peak of adult COVID-19 cases. No child should be denied a ventilator or a bed or respiratory support, yet these are the kind of decisions we had to make. We had to triage who most needed respiratory support, while watching other kids and waiting.

MORE: I was a nurse for 10 years in Scotland. So why can’t I get certified in Canada?

So many of our ICU staff were burnt out. Many people quit, and others went on extended leave to take care of their mental health. It’s not fair to rely on the altruism and resilience of these wonderful, generous people to compensate for a lack of government planning. That burden is something that every health-care worker carries with them: if I don’t show up to work tomorrow, the sick baby in the ICU is not going to get respiratory care. I remember having to say to a family, ‘I’m sorry. Two months ago your child would have met the criteria for an ICU bed, but now we just don’t have enough beds for them.’ It felt so ethically wrong. It was heartbreaking. You live with a very direct sense of responsibility. But it shouldn’t be up to good people to go above and beyond every day. It’s not a sustainable way to deliver care.”

Chelsea Cadieux, PICU nurse, Ottawa

“Late last year, I admitted a young girl after a bad car accident. Her younger brother had passed away in the same accident. Her mother was at the bedside with me, and she had to call her extended family to let them know what had happened. I remember hearing the screams that came through the phone. They replayed in my head for a long time after.

As a nurse, you try to be strong for your patients. I wanted to cry with them and hug them and let myself feel what they were feeling, but I couldn’t crumble on the ground. I had a job to do. That was the day I realized I needed to talk to someone about all the things I’d seen working in the hospital. But the problem with therapy is that even when you realize you need help, the benefits we have barely cover it. It’s really a pitfall in nursing. You’re expected to deal with all this trauma, but you’re not given the tools to cope with it.”

Christa Ramsay, PICU senior respiratory therapist, Ottawa

“I’ve been working at CHEO in the ICU for 23 years. Before the viral surge, whenever a child died, I always felt like my team and I had done everything we could to save their life. And if it was a life that couldn’t be saved, we hopefully made the dying process as painless and peaceful as possible.

During the surge, we were stretched so thin that it felt like we were never doing excellent work. We had dozens of kids, and we had to choose which ones we were going to treat first, knowing that prioritizing one might be detrimental to others. We just couldn’t do it all. And so rather than providing excellent, timely, thorough care, we were running around putting out fires constantly. I used to dread going into work. When I left, I would get in my car, cry the whole way home, pull into my garage and just sit there, crying some more. It was days upon days and weeks upon weeks of never feeling like I’d done a good job.”

Zoya Thawer, pediatric endocrinologist, Calgary

“The other day was really challenging. I got up at 5 a.m. to catch a ferry, then started my day in a busy clinic where I was helping out a colleague, and I was also on call for inpatients at the hospital. In the afternoon we had a lunch-and-learn, and it was the first time I’d sat down all day. Just as I was about to eat, I got a phone call about an urgent patient. By the time I attended to them and I was done sorting everything out, the afternoon clinic had started and I was back to work. Not only are you physically depleted when you’re working, but there’s also the mental burden of being on call—something could happen anytime that you have to respond to immediately. It doesn’t matter that I haven’t had my lunch or a proper break.

It can be really frustrating when people say, ‘Self-care is really important,’ but then when you actually look at your day, you’re like, ‘There’s nowhere I could have really taken any time for myself.’ And it’s because of how the system is structured and how much we’re expected to work. We talk a lot about burnout and how we can make people more resilient, but it’s really challenging when the system isn’t set up to support you. We’re overworked and understaffed with no time to take care of ourselves. If the system is failing us, there are very limited things the individual can do to make that better.”