Inside the Vancouver lab where scientists (legally) grow magic mushrooms

The Filament Health facility looks like something out of The Last of Us

Filament founder Ben Lightburn saw an opportunity to leverage his team’s botanical extraction expertise to bring the first pharmaceutical-grade, naturally extracted psychedelics into the market. Photos courtesy Filament)

Share

Entrepreneur Ben Lightburn became interested in psychedelics in 2018, when he read about the promising results emerging from clinical trials. He had just sold his company, Mazza Innovation, which developed botanical extraction technologies for companies producing cosmetics and dietary supplements. The psychedelics industry, he realized, mostly produced synthetically manufactured psilocybin for research and development: it’s incredibly difficult to extract psilocybin from mushrooms in a way that’s standardized and stable.

Lightburn saw an opportunity to leverage his team’s botanical extraction expertise to bring the first pharmaceutical-grade, naturally extracted psychedelics into the market. His company, Filament Health, extracts drugs like psilocybin, psilocyn, ayahuasca, mescaline and salvia primarily for research and development purposes. Psilocybin can be delivered to patients via Health Canada’s Special Access Program—physicians for seriously or terminally ill patients can use the program to request treatments that Health Canada hasn’t yet approved. Filament Health currently supplies about 70 patients across the country, most of whom are dealing with serious depression or terminal cancer.

Inside Filament’s lab, four scientists grow a variety of mushrooms, including Psilocybe tampanensis and Psilocybe cubensis (their nicknames are a bit more playful, like Jack Frost, Albino Penis Envy and Blue Meanie). Then they dry the mushrooms and mill them into a powder. After that, the active ingredients are extracted, purified, mixed with different excipients and preserved. Finally, they’re poured into capsules, packaged and sent around the globe. We took a look inside their lab to see how it all goes down.

Filament moved into their Vancouver lab in 2020 and employ four full-time staff there, including their chief science officer, a mycologist, an analytical chemist and a quality control specialist. The rest of the team works remotely, and Lightburn splits his time between the lab and home.

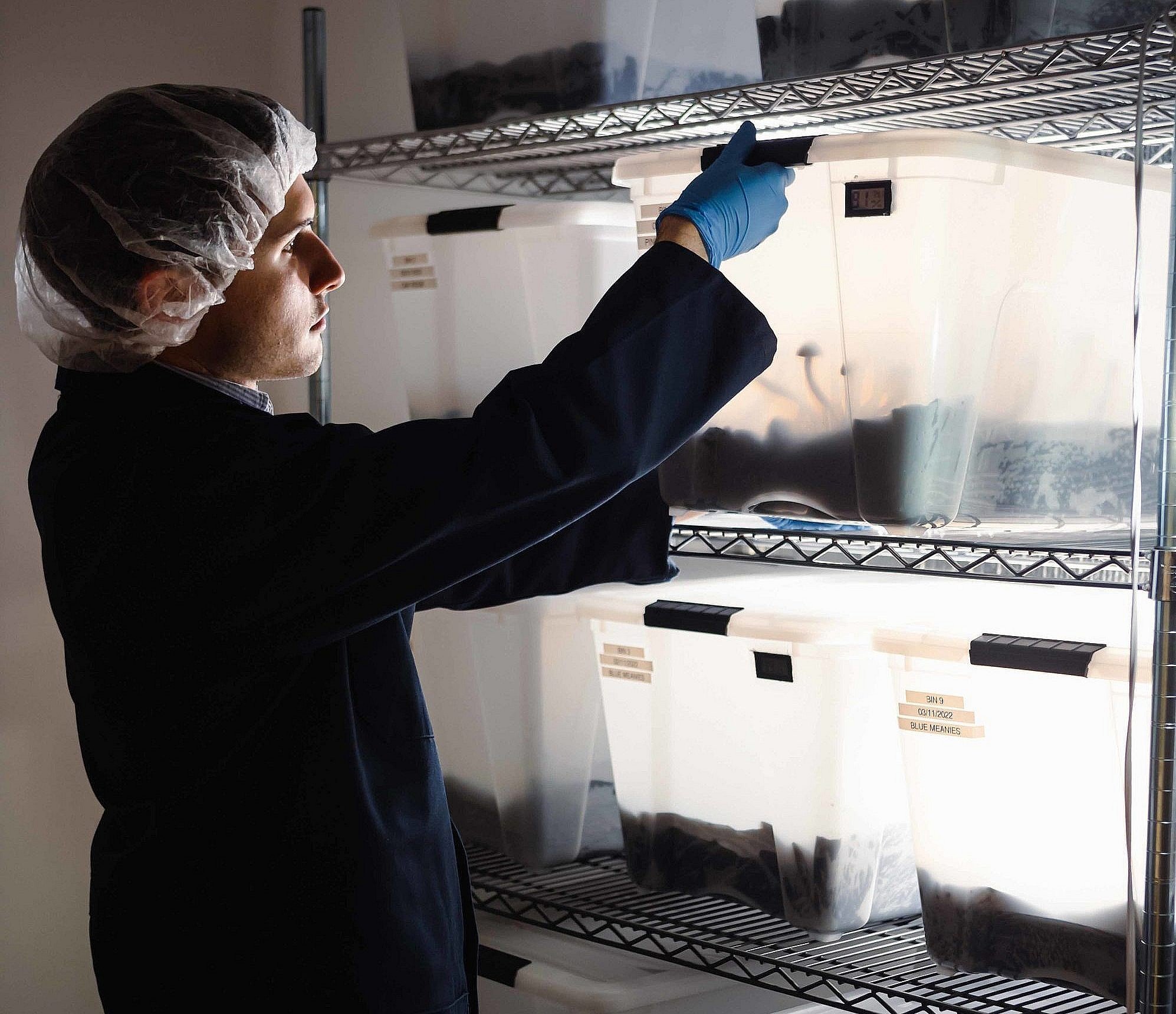

The mushrooms grow in these containers, which provide a controlled environment that optimizes humidity and minimizes contamination. The growing medium is made of organic Canadian rye grain and coconut coir. They harvest approximately 10 to 50 kilograms of mushrooms every month.

Here, lab workers are harvesting a strain of mushroom called Psilocybe cubensis. One of the reasons Lightburn thinks consumers will want naturally extracted psilocybin over synthetic is because of something called the “entourage effect,” which is the idea that a natural plant has more than just one active ingredient. “When you make a natural extract, you’re also preserving all the other compounds that are present in the mushroom,” says Lightburn. “For example, wine is more than just alcohol, and coffee is more than just caffeine.” Mushrooms also contain compounds like psilocyn, norpsilocin, baeocystin and norbaeocystin.

The harvester must delicately cut the mushroom at the base to minimize bruising.

Here, mushrooms are placed in a dehydrator before processing (Psilocybe cubensis is over 90 per cent water).

Psilocybe cubensis are grown in many substances, depending on the desired properties. These ones grow in rye grain and Coco peat fibre.

Filament grows their mushrooms for two purposes. For their own research and development, they evaluate the different strains for their potency, growth speed and resistance to contamination. For production, they go to the manufacturing side of the lab.

These solutions are used to test the compounds in the mushrooms.

This is called a rotary evaporator, used to remove a solvent or water from an extract.

These plates contain a growth medium used for germinating and propagating mycelium (the fungal threads from which mushrooms are grown).

Here are their Soxhlet extractors, which extract the active components from the mushrooms.

As for the future of legal psychedelics for all, Lightburn is hopeful. “In Vancouver, there are magic mushroom stores operating openly,” he says. “Not long before cannabis was legalized, we had cannabis stores openly operating.”