Jean Béliveau: Man for all seasons

Jean Béliveau is remembered not just for his glorious years at the rink but the stellar life he led away from it

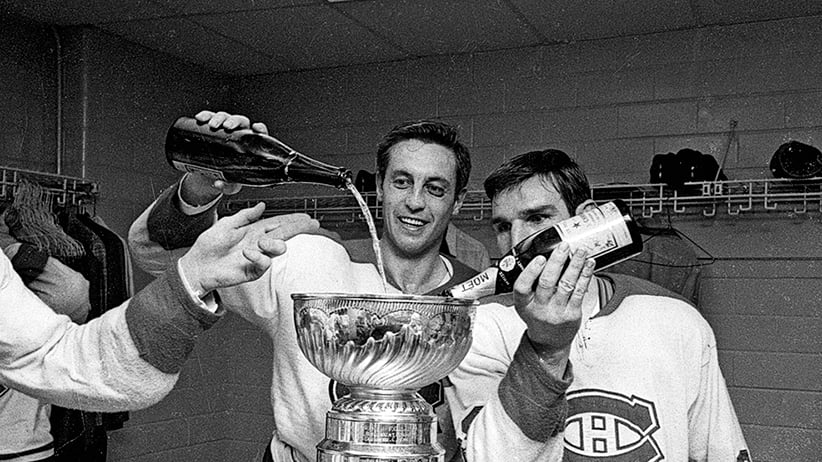

CANADA 1970’s: Jean Beliveau #4 of The Montreal Canadiens. Denis Brodeur/NHLI/Getty Images

Share

Over the course of their storied 105-year history, the Montreal Canadiens have had some pretty good luck with the number four. It’s the sweater that the diminutive Éduoard “Newsy” Lalonde, hockey’s original superstar, wore as he captained the club to the first of its 24 Stanley Cups back in 1916. And it was the digit that identified his fellow, tiny Hall of Famer, Aurèle “the Mighty Atom” Joliat over 16 seasons—and three more championships—during the 1920s and ’30s. But No. 4 has been retired and hanging in Montreal’s rafters (first at the Forum and more lately the Bell Centre) since the beginning of the 1972-73 season in honour of the outsized exploits of just one man, Jean Béliveau.

A gigantic figure both on and off the ice, Béliveau who died at the age of 83 last week, won 10 NHL championships as a player with the Canadiens, and saw his name engraved on the Cup seven more times as a team executive. The rangy, six-foot-three centre was twice voted the league’s MVP, won a scoring championship, and was the first player to ever receive the Conn Smythe Trophy as the outstanding playoff performer. His 1,219 points, including 507 goals, in 1,125 career games still numbers him among the top 40 producers of all time, 41 years after his retirement.

In 18 seasons with the Canadiens—10 of them as captain—his team missed the playoffs only once, and then by a single point. A number of Béliveau’s accomplishments, like his 62 career points in Stanley Cup finals, including nine game-winning goals, will never be eclipsed in today’s 30-team NHL.

Yet in Montreal, where tens of thousands turned out to pay their respects this week, filing past his casket as he lay in state at the Bell Centre, Béliveau is being mourned not just for his glorious years at the rink, but the stellar life he led away from it. A man of great dignity, possessing impeccable manners, Mr. Béliveau (in hockey circles his name was always accompanied by the honorific) was also one of the most approachable stars the game has ever known.

At the height of his fame in the 1950s and ’60s, when he received several hundred fan letters every week, “Gentleman Jean” penned a personal reply to each and every one. He always made time to pose for a photo, or simply chat with an admirer. And his willingness to lend his name, image and time to charities, whether it was his own foundation for disabled children or someone else’s worthy cause, was legendary.

“I don’t think he knew how to say ‘no.’ He was always there helping out at telethons or dinners or visiting kids in the hospital,” says Guy Lapointe, a Hall of Fame defenceman for the Habs during the 1970s.

Growing up in Montreal, Lapointe idolized Béliveau, and still remembers being in awe the first time they shared a dressing room at training camp. “I almost forgot to tie up my skates,” he says. They played together for just one season—1970-71, Lapointe’s rookie year and Béliveau’s swan song—but the retiring Habs captain imparted a lifetime’s worth of hockey wisdom on the way to a Stanley Cup victory. “He was a quiet and dignified leader,” recalls Lapointe, now chief amateur scout for the Minnesota Wild. “It wasn’t about individual accomplishments. Everything was about the team and family.”

Born in Trois-Rivières, Que., in August 1931, the eldest of eight children, Béliveau didn’t come from a sporting family, and only started playing organized hockey at the age of 12. His talent for the game was undeniable, and by the time he was 15, skating for a team in Victoriaville, the pros were already fighting for his services. Spurning a low-ball offer from the Habs and their farm team, Béliveau moved to Quebec City and established himself as a star with the Citadeles of the Quebec Junior Hockey League, packing the brand-new 10,000-seat Colisée Arena—known locally as “the House that Jean Built”—every night.

When he turned 19 in 1950, Béliveau, already nicknamed “Le Gros Bill” after a Quebecois folk hero, signed a $20,000-a-year “amateur” contract with the Quebec Aces of the Quebec Senior Hockey League (QSHL), bettering the salaries of both Maurice “Rocket” Richard and Gordie Howe, the NHL’s biggest names. Les Canadiens, who owned his “professional” rights, managed to entice him to Montreal for two brief tryouts, but they were unable to convince him to stay.

In desperation, the organization purchased the entire QSHL in the summer of 1953 and turned it pro. That October, after protracted negotiations involving both his financial adviser and an income tax expert, Béliveau signed a five-year, $105,000 deal with the Habs, and took a handshake $10,000-a-summer side job with the promotions department of Molson’s brewery, then the club’s owner. Rocket Richard, the team’s biggest star and captain, earned more in salary, but at just 22, Béliveau’s total take-home made him the best-paid player in the NHL. “It was always my dream to play for the Canadiens, even for the two or three years I didn’t want to sign,” Béliveau slyly explained to the Montreal Gazette in 2013.

By his second year in the league, Béliveau was an established force, averaging more than a point a game. But his breakout season came in 1955-56, when he notched 47 goals and accumulated 41 assists, winning the scoring title and his first Hart Trophy as league MVP. In the playoffs, he then added 12 more goals and seven assists as the Habs beat the Red Wings to capture the first of five consecutive Stanley Cups through the end of the decade.

The victory, a year after the infamous Richard riots, marked a changing of the guard in Montreal. The suave and handsome Béliveau was now the big star. That January, he had become the first NHL player to grace the cover of Sports Illustrated. A few weeks later, Maclean’s asked, “Is Jean Béliveau the best ever?” Trent Frayne’s classic profile of the “bland and bashful” centre is sprinkled with high-powered raves from the likes of Hap Day, Art Ross, Lynn Patrick, and even the owner of the Toronto Maple Leafs, Conn Smythe. “Béliveau is the greatest thing that could have happened to the modern game,” cries Smythe, in the manner of a man who has just found his missing laundry ticket. “Who has ever shown more savvy? Who ever got a shot away faster?”

Ralph Backstrom, a Habs teammate over 13 seasons and six Stanley Cups, says Béliveau was so magical on the ice that he sometimes had to remind himself to stop watching and play. Already their unofficial leader, the players elected him captain in 1961—almost unanimously. (Backstrom admits he voted for Boom Boom Geoffrion, his line-mate, after the intimidating veteran kept looking meaningfully at his empty ballot.) “Jean wasn’t disruptive,” Backstrom says from his home in Windsor, Colo., where he owns and operates the Colorado Eagles. “If there was a problem, he’d talk to you privately. He never embarrassed you in front of the guys.”

Even his opponents loved him. In his recent autobiography My Story, another No. 4, Bobby Orr, paid extensive tribute to Béliveau as a man who earned everyone’s respect “by playing the game the way it’s meant to be played,” and “demonstrat[ing] the kind of sportsmanship seen far too seldom in professional sports.” (Orr declined an interview request, saying he is remembering his former foe in his own, private way.)

Béliveau retired just short of his 40th birthday, after leading his team with 76 points in the regular season, and counting for 22 more during their run to the Stanley Cup. He clearly could have continued. The WHA’s Quebec Nordiques offered him an astronomical $1 million to play their inaugural 1972 season, but Béliveau, the consummate company man, turned them down. The Hockey Hall of Fame waived its three-year waiting period and inducted Le Gros Bill that fall.

He remained a very public figure the rest of his life. Béliveau was tapped by Jean Chrétien to become governor general in 1994, but turned the job down in order to remain near his recently widowed daughter, Hélène, and granddaughters Mylène and Magalie.

Gary Bettman, the NHL commissioner, told Maclean’s that Béliveau’s evident class and unerring instincts will be sorely missed. “We’ve lost somebody who couldn’t have represented the game any better. Someone who couldn’t have symbolized the things that are good about the game, any better than he did,” said Bettman. In the days following his death, the league took out newspaper ads across Canada, praising the late star for elevating the entire sport, forever. “Jean Béliveau was always the epitome of the boy whose only dream was to play for the Montreal Canadiens,” they read. “Hockey is better because that dream was realized.”

Over the two days of public viewing at the Bell Centre, Béliveau’s family maintained those high standards, with his wife of 61 years, Elise, shaking the hand of each and every person who came to pay their respects. Across the ice, three rows behind the Canadiens bench, a spotlight illuminated the seat where “Gentleman Jean” sat and cheered after his retirement. A bleu, blanc et rouge sweater with the No. 4, was draped over the back.