Leicester wins the battle over the bones of Richard III

A testy legal case over burying the last king slain in England

Share

Everything about Richard III is contested: was he a just, pious king maligned by the Tudors who seized his throne or a murderous thug who killed his nephews to gain power? Even deciding his final burial spot spawned an increasingly testy court case. Now, the High Court has ruled that he will be buried in Leicester, where he lay, forgotten, for nearly 500 years.

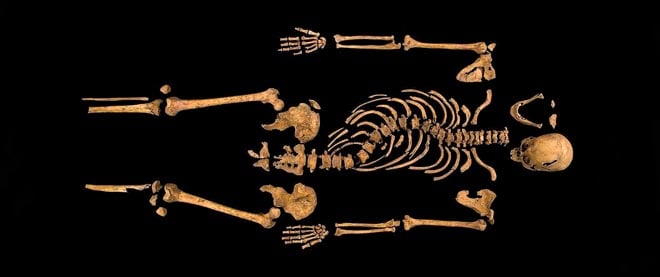

After being killed on Bosworth Field in 1485 by Henry Tudor’s invading forces, Richard had an ignominious burial, hastily shoved into a too-short grave in Leicester’s Church of the Grey Friars. Within decades the church was destroyed in the dissolution of the monasteries and Richard’s resting place was lost until a band of dedicated pro-Richard forces, led by screenwriter Philippa Langley undertook an eight-year search to find and recover his body. They raised the funds for the archaeological work and got the city to agree to the dig. They succeeded in September 2012, within four hours of starting the two-week dig, his bones were discovered in a parking lot in the English city.

That’s when the legal battle broke out. Leicester was determined he’d be buried in their cathedral, though the king had no relationship with the city, aside from his death. A group of his descendants, the Plantagenet Alliance, argued that the exhumation licence was given to the University of Leicester in error and there should be widespread consultation about his final burial place. In initially allowing the descendants’ case to proceed in 2013, Justice Haddon-Cave wrote, “In my judgment, it is plainly arguable that there was a duty at common law to consult widely as to how and where Richard III’s remains should appropriately be reinterred.” He even went so far as to offer a possible solution: “I would strongly recommend that parties immediately consider referring the fundamental question—as to where and how Richard III is reburied—to an independent advisory panel made up of suitable experts and Privy Councillors, who can consult and receive representations from all interested parties and make suitable recommendations with reasonable speed.”

That set up the High Court case. As everyone waited, Leicester continued with it’s $2-million plans to re-inter Richard III in its cathedral. Now it appears it will get its way.

In an interview with Maclean’s, Philippa Langley explained the University wasn’t supposed to be involved in the burial decision at all. “A comma caused the whole mess,” she says. Problems started with the exhumation licence application. “They don’t have enough space on them to detail all the information that you need to detail such as who the client is, what happens to the remains after exhumation: who has the permission to exhume them and who’s going to look after them. So what happened on the application form was that the archaeological contractors who are based at the university but are an independent business at the university couldn’t get their name on one line. Their name is University of Leicester Archaeological Services, so they had to put ‘Archaeological Services’ on the next line.

“A comma was inserted by the Ministry of Justice after ‘University of Leicester’ so it looked like it was the University of Leicester who were applying for the exhumation licence,” she says. “They weren’t. It was Leicester City Council.” And they’d given Langley every indication about the need to consult as to where the last king of England killed in battle would be buried. “Leicester City Council was always going to consult on the matter, and they would hold the exhumation licence,” she says. “If everything had gone as we expected, Richard would be reburied by now, and consultation would have taken place.” But things didn’t go according to plans. “I’m afraid, because of a mistake, the exhumation licence went to the University of Leicester. They took the unilateral decision not to consult.”

That is born out by the High Court ruling:

The Council’s plans continued to develop, and become more specific as to what was

to be done, both before and after the announcement about claims for alternative

reburial locations. The decision-maker was then to be the Council in consultation with

the University, and ultimately the City Mayor. However, the attempt to agree a

memorandum of understanding with the University ran into opposition from ULAS,

which contended that the Council had no responsibility for reburying or deciding on

reburial for the remains. It argued that had been dealt with by the licence and/or was

for the MoJ. Mr Buckley did not agree with the Council’s proposals for handling

competing claims for re-interment. In the end, nothing came of the Council’s

proposals for consultation, which were not made public. Reference was made in a

draft City Council press release to a more general public consultation as follows: “If

and when the identity of the remains are confirmed [sic], there will be an opportunity

for the public to comment on the plan [for re-interment in Leicester Cathedral]”. This

sentence was, however, removed from the final draft after Mr Buckley voiced

objection to it.

As it was in Richard’s time, to the victors go the spoils. In this case, it’s his body.

#RichardIII will be reinterred in Leicester. Great news for the University, our city and everybody involved in the discovery.

— Uni of Leicester (@uniofleicester) May 23, 2014