Canada’s bubbly personality

Vintners from British Columbia, Ontario and Nova Scotia are embracing effervescence

Share

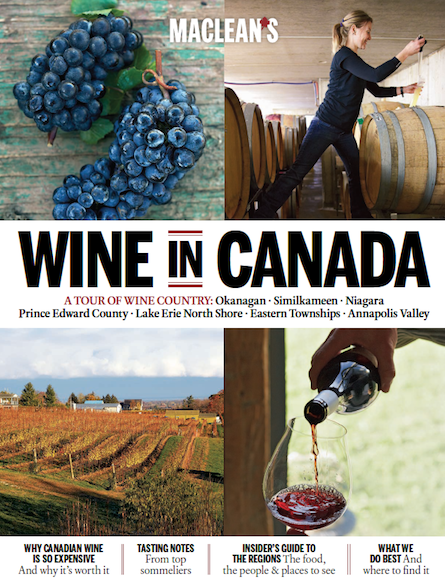

Maclean’s tells the story of Canadian wine from coast to coast in words and pictures in Wine in Canada: A Tour of Wine Country. Look for it on newsstands now. Or download the app now. In the meantime, here’s a sneak peek:

Maclean’s tells the story of Canadian wine from coast to coast in words and pictures in Wine in Canada: A Tour of Wine Country. Look for it on newsstands now. Or download the app now. In the meantime, here’s a sneak peek:

Break out the made-in-Canada bubbly. Champagne isn’t just for drenching champion athletes, New Year’s revelry and the French anymore. Producers at home are challenging the famed region’s monopoly on the finest sparkling wine.

Nestled among the rolling green hills of Nova Scotia’s Annapolis Valley near the Gaspereau River, Benjamin Bridge is part of the new wave of Canadian vineyards creating a buzz with high-calibre bubbles.

Last year a $75 bottle of its 2004 brut reserve stunned some of the country’s most discerning palates in a blind tasting—they preferred it to a $250 bottle of Louis Roederer 2004 Cristal (yes, that Cristal, from one the world’s top champagne houses).

In 2011, L’Acadie Vineyards—also from the Annapolis Valley—won a silver, the only medal awarded to a North American vineyard, at an international competition for sparkling wines held, where else, in France. And the Okanagan’s Summerhill Pyramid Winery won the “best bottle fermented sparkling wine” at the 2010 International Wine and Spirits competition in London. With a growing list of Canadian wineries chasing that bright and delicate zing, competition for the top national sparklers has become fierce. It may not be champagne, a name reserved for wines made in that region, but it sure tastes like it. And Canadians are lapping it up.

Last year, sales of Vintners Quality Alliance (VQA) Ontario sparkling white wines increased 35 per cent over 2011 to $1.3 million, according to the Liquor Control Board of Ontario, and rosé sold close to $357,000. Out west, the B.C. Liquor Distribution Branch saw local bubbly sales hit $7.3 million in 2012, a 10 per cent jump from 2009, made more significant by the fact that the number of bottles sold actually decreased—meaning consumers spent more on pricier vintages. From the Okanagan Valley to the Niagara Region, from Prince Edward County to Nova Scotia, wineries have seen the demand for sparkling spike.

“Champagne was the last stranglehold that the French had on the wine market,” says Paul Speck, president of Henry of Pelham, a Niagara winery that produces the award-winning cuveé catherine brut ($30). “I think we’ve demonstrated that we could make great sparkling wines.”

Climate is key. Cooler temperatures during the growing season produce grapes with higher acidity than warmer climates. “That brightness and freshness and vibrance” in top champagnes requires that relative chill and resulting acidity in the grapes, notes Peter Gamble, head consultant for Benjamin Bridge. The deep flavours in the best sparkling wine develop as the grapes slowly ripen on the vines. Conditions in the Annapolis Valley aren’t just pleasantly cool, he says, they’re almost identical to the Champagne region. Gamble has studied two prime Champagne seasons—1979 and 1990—and found the growing conditions were remarkably similar to the 2004 season in Nova Scotia. The winery has even partnered with nearby Acadia University to study Champagne’s climate, which has been warming over the last few decades, and compare it to local weather data.

The environment is right, owner Gerry McConnell believes, to produce “world-class sparkling wines in a place that no one would ever think that you could do it.”

Like Benjamin Bridge’s 2004 brut reserve, which bested the Cristal, most of headline-grabbing bubbly is made using the traditional French Champagne method—or the méthode classique. Still wines are made first (many based on the traditional chardonnay and pinot noir blend). Then yeast and sugar are added to each bottle to create the bubbles as the wine ferments for 30 months or more. After that, sediment is strained out, the bottles are topped up with more wine or sugar water. They are corked and stored for another six months at least, and in some cases, years.

Which is perhaps why momentum in the sparkling market is only now gaining real steam, when some—like the Okanagan’s Blue Mountain Vineyard and Cellars—have been crafting bubbly since the late 1990s.

“In the beginning sparkling wine was definitely a tough sell for us,” says Matt Mavety, winemaker and owner of Blue Mountain. “There would have been times we thought, ‘Is this the right product to see in this market?’ ”

Now in addition to wide distribution across B.C., they export sparkling wine to Alberta, Ontario, Quebec, and even south of the border to Washington, where it sits on shelves next to French champagne. Sparkling is still only 25 per cent of the winery’s business, Mavety notes, but that niche can still make a big splash. Blue Mountain crafts a highly rated brut rosé 2008 and a 2005 reserve brut. Along with two other major players—Summerhill Pyramid and Sumac Ridge Estate Winery—they’ve built “huge growth” and interest in local sparkling wine. Other producers are now making small batches, 100 or 200 cases worth, and Mavety has heard rumours a few more wineries are making significant investments in the special equipment that sparkling requires. That means more competition, which, he argues, can only be good. “That’s positive. If we can go with a group of dedicated producers serious about it, we can make a name for ourselves on the export market.” He doesn’t say it, but the implication is there: Could the Okanagan be the new Champagne, too?

Of course, Prince Edward County would have something to say that about that, including Hinterland Wine Company and their lineup of exclusively effervescent wines. With an earthy name and a modern, cool label, Hinterland stands out as a decidedly unfussy option for fizz. “There’s a new wine-buying public in our mind, and they’re far less stodgy about where wines come from,” says part-owner Jonas Newman. “They’re far more concerned with the quality; they’re far more concerned with the experience; and they’re far more experimental in their buying.” Hinterland is even doing away with the bottle all together, and selling stainless steel kegs of sparkling wine to a select few restaurants, where it will be sold on tap. Because they produce just 3,500 cases a year, he says, they can take more risks, and “not everybody has to like us.”

He adds the winery is benefiting from a groundswell of interest along with a new understanding: “You don’t have to drink champagne to get the champagne experience.”

Hinterland’s wines includes one unique bottle: Hinterland Ancestral ($25). The spritz comes from just one fermentation. It’s actually more traditional than méthode classique, hearkening back to the original single-fermentation French bubbly. It gained high praise among 18 sparkling wines from across Ontario served at a wine and food tasting held at Trump International Hotel and Tower in Toronto in December, hosted by the Wine Council of Ontario and attended by some of the province’s top wine aficionados. And it wasn’t all seafood on the plate. Sparkling with braised veal shank, sparkling with duck a l’orange. The tasting underscored a point that wineries are hoping will catch on. “Sparkling wines can pair with any foods,” Trump Towers sommelier Zoltan Szabo says with force. “Any!”

Indeed, getting the wine-loving public to think of fizzy as a daily, and even main-course, delight has been a battle—with a few victories.

Hinterland held its own tasting at the Wellington Gastropub in Ottawa in January, where three sold-out dinners for 18 people each introduced the curious and the converted to sparkling wines paired with steelhead trout served with crab mayonnaise, veal sweetbreads (pancreas) and smoked-onion purée. And in a more traditional pairing, bubbly with dessert: a vanilla pannacotta and stewed rhubarb.

“We were a bit anxious as to how things would go,” admits Wellington co-owner Shane Waldron. But when the first dinner sold out in a day, they added two more. There’s a versatility in sparkling wines that people are just beginning to discover, Waldron says. “You can get some very bold, some light and effervescent, more bubbles, less bubbles, dry, sweet, you have quite a wide canvas.”

But for a price. Most Canadian sparkling wines start at $25, and can go as high as $120 a bottle. Henry of Pelham’s $30 cuvées are “not cheap,” Speck admits. And they compete with popular $12 proseccos—and true champagne, which he says “still dominates, there’s no question.” And yet most wineries are doing a swift business, like Benjamin Bridge’s Nova 7—a $25 bottle that’s built a cult following. “Last year we did 4,500 cases,” notes McConnell. “This year it will be 9,000.”

Perhaps the race to be “the new Champagne” isn’t such a light-headed idea, after all.