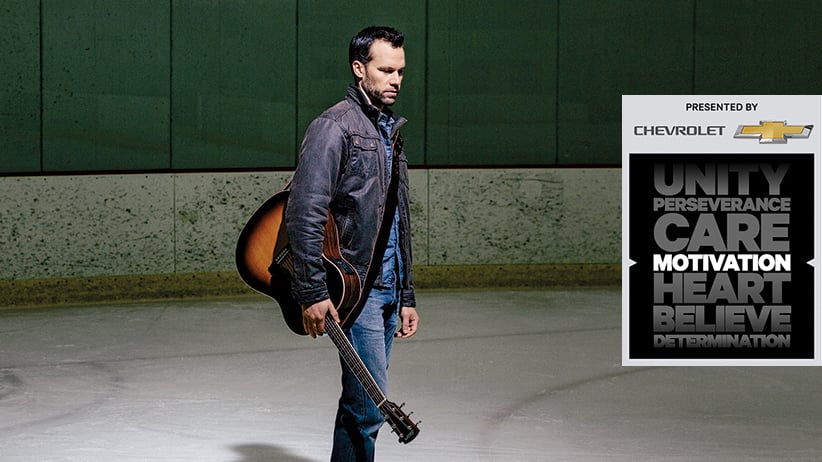

Chad Brownlee’s hurtin’ music

Injuries forced Chad Brownlee out of the game he loved, and into something else that needs courage and commitment: country music

Share

Chad Brownlee isn’t the first professional hockey player to suffer a separated shoulder—but he’s likely the first to take that as a cue to become a country music singer. The Kelowna, B.C., defenceman was drafted by the Vancouver Canucks in 2003, and was playing his first pro season with the Idaho Steelheads of the ECHL in 2008, when he decided to give up hockey for good. He’d just come back from his latest injury, and was finding the game had become a grind. “I remember the moment,” says Brownlee. “I was sitting on the bench looking up at the clock and wishing that the game would be over. I rode out the rest of the season, but in the back of my mind I knew exactly what I wanted to do.”

Within the year, Brownlee was in Nashville with some of the city’s finest songwriters, and recorded a single that would go on to crack the Top 20 on Canadian country radio. This month, he’ll release his fourth album. What’s his secret to success? No one knows better than his mom: “He works very hard,” says Laura Brownlee. “It wasn’t 100 per cent talent. He’s very goal-oriented.”

Hockey and music have often gone together, but very few players have gone from one to the other. New York Rangers goalie Henrik Lundqvist plays guitar in a rock band with John McEnroe. Former Red Wing Darren McCarty used to spend the off-season singing and touring with his band, Grinder. But it’s rare to see a blueliner become a heart-on-your-sleeve singer-songwriter. “I heard Chad was a hockey player,” says Canadian country music artist Patricia Conroy, who wrote with Brownlee in Nashville. “I thought, ‘Hmm, this should be interesting.’ He shows up, this really good-looking athlete, and he started singing. I was impressed with his voice and his whole demeanour. He’s got this sweet soft soul to him that I wasn’t expecting from a hockey-player dude.”

Brownlee, 31, taught himself to skate at four years old and asked his parents to sign him up for hockey at age six. “I was a pretty intense kid,” he says. “I was really self-motivated, very focused, very driven and wanted to improve upon myself from the previous day. I don’t know where that came from but it was a fire that grew pretty quickly in me from a young age.” At the time, music came second: he gave up piano lessons at age nine because it wasn’t “cool” and had only a short stint with the tenor sax in middle school. He dropped track and field and volleyball as well to focus on his main sport. “He wasn’t just another hockey player,” says his midget coach, Ken Andrusiak, “he had those things that you try and teach kids. It was sort of built into him.” He also had great hands—and could play every position. “I would play a shift at right wing, back to defence, and then to centre,” says Brownlee. It wasn’t until Junior A, with the Vernon Vipers, that he settled at defence.

During his second season in Vernon, Brownlee won a full-ride scholarship to Minnesota State University, Mankato—and became a prospect for the 2003 draft. He was expected to go in the fourth round. Only the first three rounds were broadcast on television, so Brownlee went to bed without knowing his fate. “I barely slept that night,” he says, “it was Christmas times 10. I got a call from my agent the next morning. He told me the Vancouver Canucks, the team I grew up cheering for, had drafted me in the sixth round.” Later, the family missed the welcome phone call from Brian Burke, the Canucks’ general manager at the time. “He left a fairly lengthy voicemail message that we kept for as long as it could possibly be saved,” says Brownlee. “I listened to it about 50 times.”

It was in Vernon that Brownlee picked up the guitar. By going online he taught himself to play a few cover songs: Simple Man by Lynyrd Skynyrd, 3AM by Matchbox Twenty and Lightning Crashes by Live. It was enough to entertain his friends at house parties once he got to university. In his senior year, Brownlee wrote and recorded a tribute song to a nine-year-old fan of the university’s hockey team, who died of leukemia. “He became a little brother to a lot of us,” says Brownlee. “We’d go to his house and play street hockey with him and his parents would cook us dinner. We were there the day he passed away.” Brownlee wrote The Hero I See in an hour and a half. Members of the community helped him record and sell it. All proceeds went to the Anthony Ford Fund. “He started the foundation before he passed away,” says Brownlee. “That’s how remarkable he was. He knew he was dying, so he said he wanted a foundation to raise funds for other kids to play hockey.”

At Minnesota State, Brownlee studied psychology and was named captain of the hockey team in his senior year. But the injuries were piling up—concussions, pinched nerves, and, after numerous dislocations, he needed surgery on both shoulders. “He was so far away,” says Laura, “it made me want to cry. He managed through the first surgery with help from some friends. But for the second one we went down and stayed with him. The other boys who lived there looked out for him, but not like a mom.”

Most summers Brownlee made it back to B.C. to skate with the other Canuck prospects, but by the time graduation rolled around he hadn’t been signed. So it was off to Idaho to play for the Steelheads in the ECHL. Halfway through the season Brownlee’s shoulder separated and he was out for a month and a half. “When I came back,” he says, “I just wasn’t the same player: a stay-at-home defenceman who needs his strength and his faculties in the corners and in front of the net—that was diminished for me.” In pain, and not getting the minutes he was used to, Brownlee closed the book on hockey after one season in Idaho. “It was a huge gamble to stop playing the game I’d been doing since I was six years old,” he says, “and jump headfirst into an industry that I have no idea about. I didn’t know a single person in music. All I knew is that I could write songs fairly well and I could sing in key and my pitch was pretty good.”

Brownlee moved in with his sister in Vancouver. While working as a server, he became an open-mic regular in Kitsilano. “You go early, sign up, play your three songs for the eight people that are there,” says Brownlee. “It was scary, but there was this voice in the back of my head that said, this is the path you’re supposed to go on.” After he took out a $20,000 loan to record a six-song EP, things started to move quickly. He was introduced to Mitch Merrett, a Vancouver-based producer and manager, who sent Brownlee to Nashville to work with songwriters, including Conroy and Tebey Ottoh. More hockey player than music nerd, Brownlee knew nothing about the city’s legendary scene. “I just thought they were friends of Mitch’s who wrote songs,” says Brownlee. “But they were spitting out ideas so quick, they had the first verse done by the time I had one line.”

Brownlee’s first single, The Best That I Can (Superhero), went Top 20 on Canadian country radio. He’s added a bucketful of awards since, co-headlined on tour with Dallas Smith and been twice nominated for CCMA male artist of the year (along with a Juno nomination for best country album in 2013).

While Brownlee has no regrets about giving up hockey, he still likes to play. While on tour, he’s skated with the Winnipeg Jets and the Kamloops Blazers, and he’s a secret weapon for the musicians’ team at the Juno Cup, the annual hockey game between Canadian artists and former NHLers. “I guess I could have played on either side,” says Brownlee, “but my allegiance is to my fellow musicians.”

Conroy jokes that Brownlee went from skates to rhinestones; it’s clear one still influences the other. “Hockey really taught me the commitment level you need for something in order to be successful at it,” says Brownlee. “It’s not that I have any extra abilities beyond anybody else. I just have the drive and commitment to become better at something.”

The most rewarding part of all has been connecting with fans. At a show in Winnipeg, a woman told him that his song Listen saved her marriage. She and her husband were sitting at a table, about to sign their divorce papers, when his song came on. The lyrics gave them pause, and they stopped what they were doing. The relationship, she told Brownlee, has never been better. “It’s moments like that,” he says, “that really keep me going.” There might even be a country song in there somewhere.

In partnership with Sportsnet