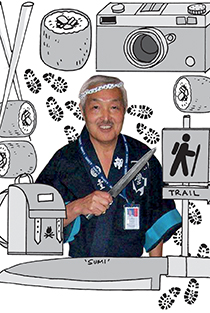

Susumu ‘Sumi’ Yoda

A photographer since boyhood, he’d lived all over Canada. But his heart remained in eastern Canada, with its majestic shores.

Team Macho

Share

Susumu Yoda was born near Tokyo on Nov. 26, 1947, two years after U.S. atomic bombs annihilated Hiroshima and Nagasaki. He had two siblings—a sister and a brother—and like millions of other children, they grew up in a country shattered by the Second World War. Starvation was rampant.

Yoda was four years old when Allied forces ended their occupation of Japan, ushering in a new era of democracy and economic reform. His dad, lucky enough to find work, bought Yoda a gift he never forgot: a new camera. (The first Polaroid was introduced in 1947, the year he was born.) Yoda carried that camera everywhere, capturing countless photos of the world around him.

As a young man, Yoda shuffled between jobs, mostly in the construction industry. He also trained as a chef, learning the art of fine Japanese cuisine. But the work hours in his home country were gruelling—he later told one friend, “They don’t give you any time to yourself.” He longed for something more satisfying. After his father died of cancer, Yoda made up his mind and packed his bags. He arrived in Nova Scotia in 1978.

His trade took him to restaurant kitchens across the country, from Halifax to London to Edmonton to Vancouver. But his heart always remained in Atlantic Canada, whose scenic shores and mountainside views made for spectacular photographs. He returned east in 2005, settling in Bedford, N.S., and taking a job as a line cook at Casino Nova Scotia. “He was calm, very professional and made the best sushi around,” says Curtis Sparks, his former boss. “He showed me some of his secrets.”

Yoda sported a grey moustache and bowed when he said hello. At work, everyone called him “Sumi” for short. “He was a wonderful person, always very nice and very pleasant,” says Heather Hurshman, who worked in the casino’s pastry department. “He was one of those people who was devoted to coming to work every day and doing his job to the best of his abilities.” And when it came to sushi, she says, nobody was better. “He always said it was the rice,” Hurshman recalls. “Making the rice not too sticky—but a certain amount sticky. A lot of people he tried to teach could never do it as well.”

When he wasn’t perfecting his sushi, Yoda was the unofficial staff photographer, snapping away at Christmas parties and other social gatherings. He talked often about the remote camping trips he liked to take, just him and his camera. “He loved to travel, and he loved taking pictures of nature and the mountains,” says Paula Vatavu, whose mother, a Romanian immigrant, also worked with Yoda. “When my mom came to Canada, this was her first job. Her English wasn’t that great and she really didn’t have friends. He was one of the first ones to really befriend her. He was just such a nice person.”

He was also a frugal man who, despite a modest salary, owned his home and his car. He drank two cups of coffee a day (one in the morning, one after work) and never gambled, even though the slot machines were mere steps away. “His personality was so great, such a pleasant guy to be around,” says Manohar Ahir, a fellow cook who worked right beside him, chopping and slicing, for six years. “He would help you without you even asking. If he sees you have a little bit of extra work, he will just come and join you. And that means a lot in our business.”

“I considered him my best friend,” Ahir continues. “When I work in the kitchen now, I still think that he’s going to appear from the corner. My heart cannot accept that he is gone.”

Last month, after they had finished yet another shift side by side, Ahir wished his friend a good trip. Yoda and his camera were heading to Meat Cove, at the northern tip of Cape Breton Island, for a few days of camping and hiking.

As so many others do, Yoda pitched his tent just two metres from the edge of one of Meat Cove’s steep, rocky cliffs—waking up to a stunning sunrise. On Aug. 24, a Friday, another tourist spotted Yoda’s body at the bottom of the mountain, 150 m below his campsite. “He was alone when this happened, so we may never have a total picture of how he actually fell,” says RCMP Sgt. Bridgit Leger. “But we do not believe foul play was involved.”

Speculation aside, it also doesn’t appear that Yoda slipped in pursuit of the perfect photograph. Police found the 64-year-old’s beloved camera inside his car.