The pandemic zapped James Jones’s career. Then, his TikTok videos relaunched it.

The accomplished hoop dancer went mega-viral while introducing TikTok audiences to a cherished part of his Cree heritage

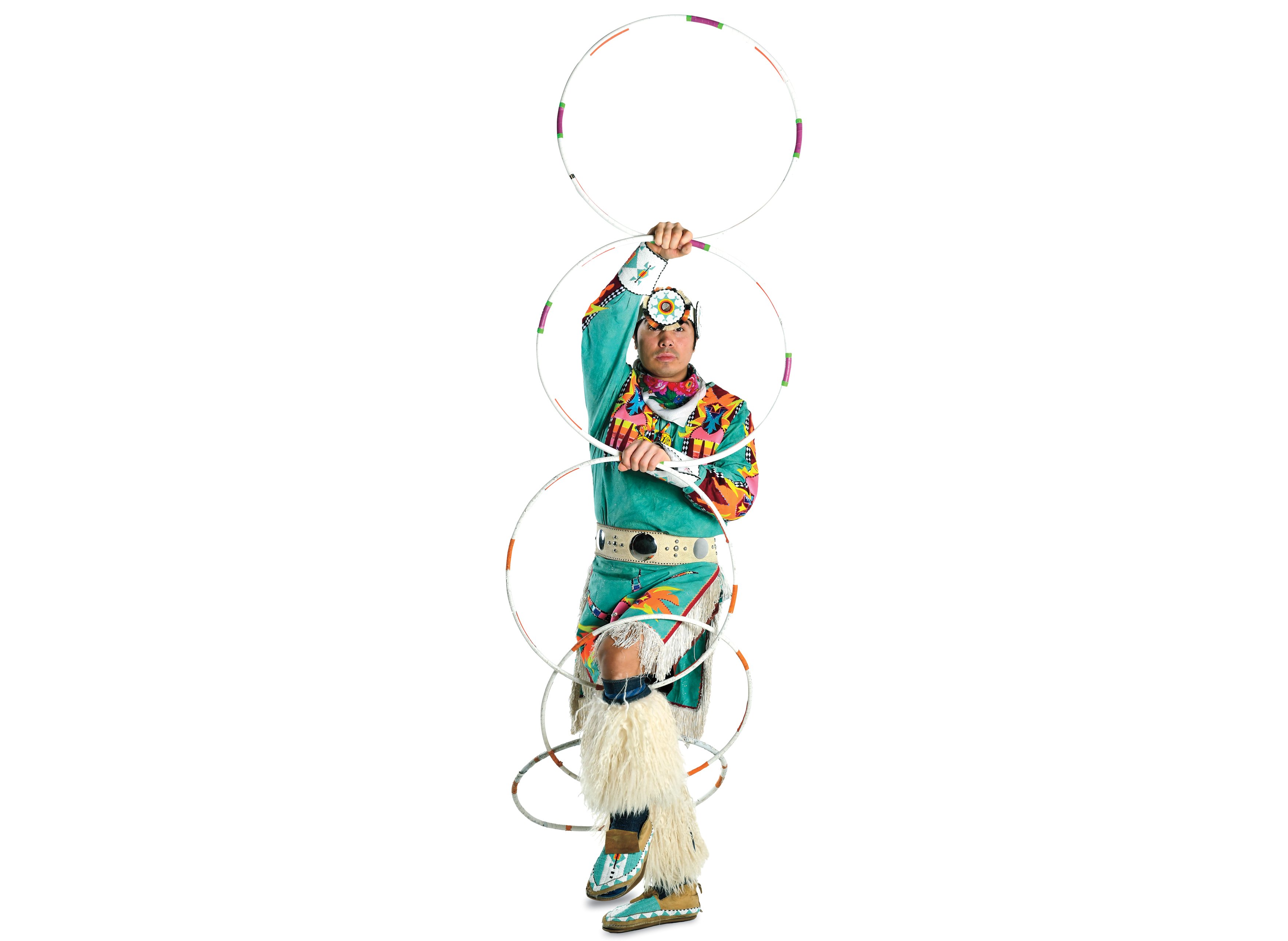

James Jones. This portrait was taken in accordance with public health recommendations, taking all necessary steps to protect participants from COVID-19. (Photograph by Candice Ward)

Share

Pandemic boredom and underemployment led Canadians to bake sourdough, learn cross-stitch or play Animal Crossing. James Jones became a TikTok sensation.

An accomplished hoop dancer who’s performed internationally, Jones saw a calendar full of gigs and in-person youth engagements wiped out last March, and found himself housebound in Edmonton. He’d downloaded TikTok on his phone, but the 34-year-old felt a little old and uninterested in a social media app dominated by short, trendy dances. But he found a corner that intrigued him: Indigenous TikTok, where artists like him conveyed educational and cultural messages with a liberal dose of wit and self-effacement. He donned the moniker @notoriouscree and tried it out.

After his first few videos got little traction, he joined a trend that invited users to dance to the Weeknd’s hit Blinding Lights. He shook it in full regalia and three hoops in each hand, forming wings. The post exploded, with 500,000 views overnight. “It sent my account into high gear, and set everything off,” Jones says. “It’s definitely allowed me to share my story and share my message with a lot more people.”

READ: Why Laurent Duvernay-Tardif put his NFL career on hold for his community during the pandemic

He now has 2.6 million followers tuning into his near-daily clips. To say he’s a poster child for TikTok success is to speak literally—he was featured in an ad campaign for the app last fall that included a billboard in Toronto’s Yonge-Dundas Square.

Though he was born in Alberta’s Tallcree First Nation, closer to the Northwest Territories than any city, Jones got into traditional dances as a teenager in Edmonton’s hip hop and breakdancing scene, exposed by friends who were also powwow dancers. A mentor taught him the hoops when he was in his 20s, and his talents have landed him everywhere from the 2010 Vancouver Olympics and the Sydney Opera House to So You Think You Can Dance Canada and a world tour with the musical group A Tribe Called Red. Within weeks of the pandemic zapping much of Jones’s livelihood, his TikTok fame had relaunched his career right from his living room. The attention has brought requests for virtual performances, online speaking gigs, and various advertising campaigns and influencer sponsorships.

READ: Derrick Rossi, the co-founder of Moderna, got the Pfizer vaccine and he’s happy about it

Hoop dancing to pop songs forms a mere fraction of his posts. More often, he’ll dance to traditional drum songs—and they draw more views. Many offer messages about Indigenous culture, ranging from pride in his long hair and braids, to land rights, to cultural appropriation.

Jones says he hears from young non-Indigenous followers who were scarcely aware of the issues he makes videos about. He hears from young Indigenous Canadians—and Americans—grateful to be reconnected with the ceremonies and traditions of their peoples, knowledge they might not have grown up with. With his hoops, and with his furniture cleared away from one end of his living room, he’s thriving on TikTok on his own terms. “We can raise awareness and tell our stories the way we want to tell them on these platforms,” he says, “just like anybody else can.”

This profile appeared in the April 2021 issue of Maclean’s, where we gave our magazine over to a 22,000-word special report, “Year One: The untold story of the pandemic in Canada.” Read that whole story, and learn why we did it.