The trouble with companies asking workers to get microchip implants

If your employer offered to inject a small microchip into your hand to replace all the keys and passcodes you need for work, would you accept?

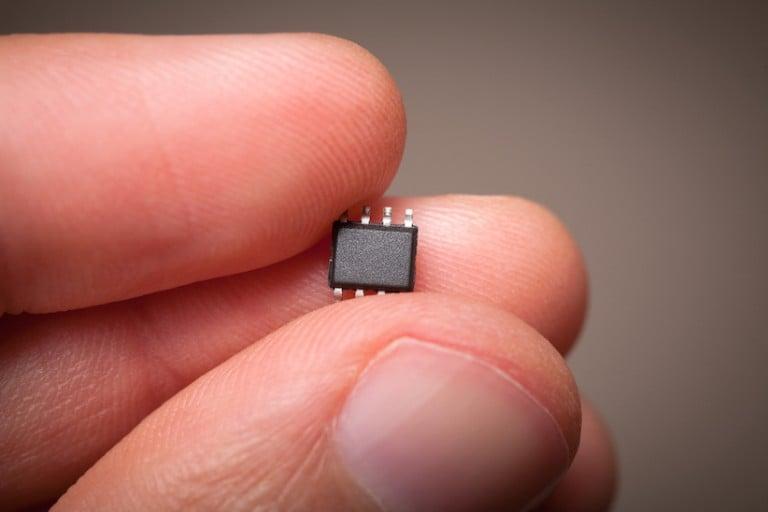

(Shutterstock)

Share

If your employer offered to inject a small microchip into your hand to replace all the keys, cards and passcodes you need to make it through a day at the office, would you accept? The Swedish start-up hub, Epicenter, is doing exactly that and scores of employees have already taken them up on it. With a wave of their hand, the company’s microchipped employees can do things like unlock doors, access photocopiers and buy coffee at the company cafeteria. Many employees and the company’s CEO are enthusiastic about improved efficiency and convenience. But when they agree to the injection, do people really understand what they’re getting into—or what’s getting into them?

The devices are about the size of a grain of rice and are implanted just below the thumb in the fleshy part of a person’s hand. Using the same Near Field Communication (NFC) technology found in many touchless payment cards and key fobs, the microchips must pass within four centimeters of a receiving device to enable access to services that have been set up to accommodate microchipped employees. Notably, the chips are passive devices, meaning they contain information that external devices can read, but do not themselves read or receive information.

The privacy implications of implanted microchips worry some people. Implanted chips give employers, or anyone with a properly calibrated reading device, a way to track certain activities—such as when a person arrives and leaves work, how many photocopies they make, or what they order at the company cafeteria. But this seems no different than employers’ existing ability to monitor behaviour through employees’ use of external key fobs, cards and smartphones. The only salient difference seems to be that while you can leave your smartphone or wallet in another room, you can’t disconnect from an implanted microchip with ease.

What about health and safety? The chips pose similar or lesser health risks as other implanted devices—such as pace-makers and IUDs—but these are manageable. Crime associated with implanted chips is unlikely to be much different than what we face when our credit or debit card information is skimmed by unauthorized readers—which is to say that there is risk, but not a novel risk, nor one that we have not already implicitly accepted. There could be increased physical risk if muggers who previously would have simply stolen wallets must now steal microchipped hands. But that would be an extraordinary escalation with limited return for criminals, especially if chips could be deactivated with a simple phone call.

More pressing ethical issues relate to autonomy and consent. The Swedish company, where 150 employees and others who use their facilities have already received implants, maintains that everyone freely consented and that those who do not want the chips are free to refuse. Although no one appears to be actively pressured or coerced to receive an injection, we might be concerned about the almost cult-like atmosphere and peer pressure that seems to accompany the parties that are held for those being injected with new microchips. Might those who refuse the implant be seen as disengaged employees, rather than educated adults exercising their autonomy and right to bodily integrity?

Even if informed consent at the point of initial injection is respected, we might ask whether people who receive chips will be made aware of, and have opportunities to accept or reject, new uses for the chips in the future. Employees who are microchipped consent to the use of the technology for a discrete set of functions at the point of initial injection. But microchips that open doors and activate photocopiers today could later be used to track how long employees use their keyboards or how often they use the washroom. By installing reading devices throughout the workplace, employers can monitor activity in ways to which employees might not have consented at the outset. To be sure, the ethics of employers’ intentions and decisions matter here as much, if not more, than the technology itself. But the technology does make it easier for employers who would sidestep issues of informed consent to do so.

Implanted microchips might appear to raise only minor ethical issues. But as with many new and emerging technologies, it is important to consider incremental and long-term changes that technologies can have on our lives, relationships and communities. Years of seemingly small changes can produce futures that we would not have chosen for ourselves had we considered long-term implications. Which is not to say you shouldn’t get a microchip implant. If the convenience of not carrying keys and cards outweighs the inconvenience of a small injection and future uncertainty for you, then take the jab. But the next time you shake hands with someone, think about what you might be passing on to them in addition to the season’s latest flu virus.

Daniel Munro teaches ethics in the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs at the University of Ottawa. Listen to The Ethics Lab on Ottawa Today with Mark Sutcliffe, Thursdays at 11 EST.