What is xylazine, the dangerous new drug fuelling Canada’s opioid crisis?

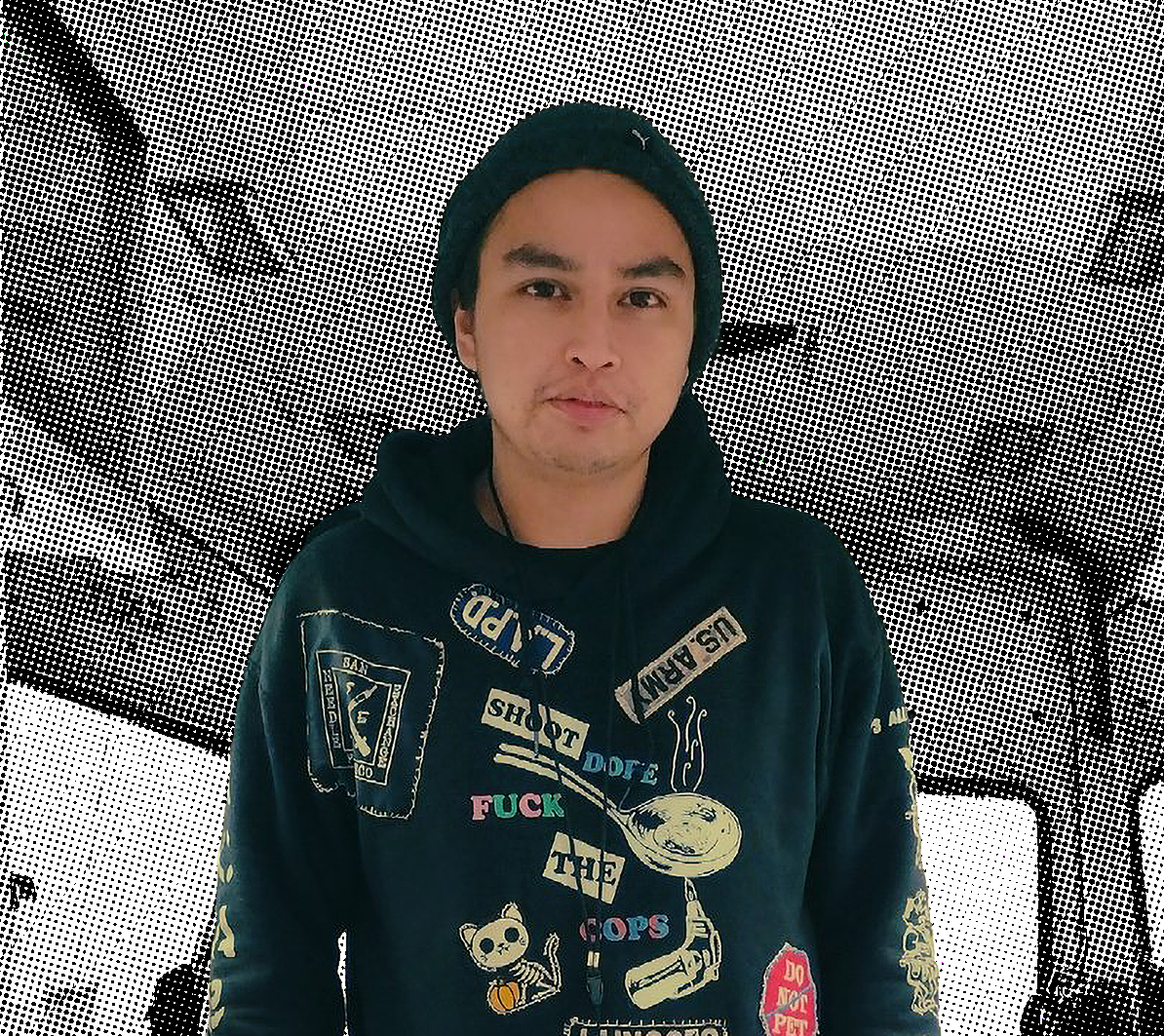

Kali Sedgemore, a harm-reduction worker in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, has seen its impact firsthand

Share

Last year, there was an average of 20 opioid-related deaths in Canada each day. This year, a dangerous new substance, xylazine, has been further amplifying the toxicity of Canada’s drug supply, concerning first responders and public-health experts who work on the front lines.

Xylazine, known by some users as “tranq” or “zombie drug” for its powerful sedative effects, is a tranquilizer typically administered to large animals (like horses) in veterinary settings, and is not approved for use in humans. According to a recent report from Health Canada, xylazine was found in 1,350 samples of drug seizures, most commonly in Ontario and British Columbia. Perhaps most alarmingly, the sedative is sometimes combined with fentanyl. But unlike fentanyl, whose overdoses are treated with naloxone (or Narcan), xylazine currently has no antidote.

READ: I’m a family doctor in Halifax. Here’s why pay-for-service clinics will burden the public system.

To find out more about xylazine, its devastating effects on users and what can be done to mitigate them (if anything), we spoke to Kali Sedgemore, a long-time harm-reduction expert in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside who also works with Vancouver Coastal Health, a regional health authority that provides addictions outreach in British Columbia.

How did you get involved with harm-reduction work?

I grew up surrounded by substance use. At 11, I started using cocaine and alcohol, which turned into a habit as I entered high school. It progressed to crack and, later, meth. Now, I’m a daily intravenous meth user. I’ve also watched family members use. I know the importance of having clean supplies and treating drug users with respect, knowing they need help. For the past 10 years, I’ve been working to prevent people from overdosing. Right now, I work at three safe-injection sites in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside.

What’s a typical work day like for you?

I usually work from noon to 8 p.m. I arrive at the site, which is usually a big room with a bunch of different stations where people can use. We see anywhere from 40 to 100 people a day, and all types: construction workers, unhoused people, lawyers. I sign them in, witness their consumption of drugs—including fentanyl, crystal meth, hydromorphone, cocaine, ritalin, dexedrine—and try to help them as best I can. Some users have seizures, or they black out or fall asleep. Some act erratically. Some stop breathing, because opiates tell the body to slow down, reducing their oxygen supply. If this happens, two or three workers will offer them oxygen. If someone “goes down,” which is the term we use for overdosing, we give them naloxone, which reduces the effects of opioids and restores breathing. We’ll call 911 if we do that.

How have you seen the opioid crisis evolve over the years?

When I started working in harm reduction back in 2011, drug dealers were mixing fentanyl with other drugs—like heroin, cocaine and methamphetamine—because it’s a cheap way to get high. I wasn’t really seeing any overdoses until 2015, when fentanyl fully entered the drug supply. We didn’t know what was going on at first. By the winter of 2022, we were seeing one or two overdoses a day at the clinic. And by early 2023, we were seeing between five to seven overdoses a day, which we attribute to an increased presence of xylazine and benzodiazepines like Xanax, Ativan and Valium.

So xylazine really emerged earlier this year?

In January, I started hearing about xylazine through drug warnings on social media. One Instagram account, Harm Reduction Saves Lives, posts regular updates on the province’s supply. Then outreach workers end up discussing it at testing sites. We don’t see xylazine as the new fentanyl, exactly; it’s just another example of how the drug supply is being contaminated. We know that xylazine is a veterinary tranquilizer, but we’re not sure how the drug dealers are getting it from clinics.

How does xylazine enter the drug supply?

It’s used as a filler to create more product and increase its potency, which jacks up the price of the drugs. This is a process called “cutting.” Often, the presence of xylazine isn’t the fault of individual dealers, because the drugs have usually switched hands a few times before they get them. Lately, we’ve been seeing a lot of long-time users overdose. These are people who have a high tolerance and a lot of experience using, which is a sign that the drugs are getting more toxic.

READ: An impossible job: What it’s like to work in a pediatric ICU

What about xylazine makes it particularly dangerous?

First, it’s meant for animals. It’s also difficult to tell whether someone has taken drugs cut with xylazine, which is usually injected or smoked with tin foil or a bubble pipe. We’ve seen different physical responses to it; sometimes it just looks like someone is heavily sedated. Because xylazine is a tranquilizer, though, it can cause some people to black out for 12 hours. It’s also a vasoconstrictor, meaning it causes a narrowing of the blood vessels, which can cause really bad skin abscesses and leads to amputation in some instances. Most of all, we have no readily available way to test the drugs and find out what’s in them—unless we send them in for testing, which we don’t have the time or resources to do.

In your opinion, does xylazine have the potential to wreak as much havoc as fentanyl?

It’s hard to say. Nobody knows what to do at this point.

Is there any action that policymakers can take?

We need a regulated, safe supply of drugs—as in, we need dealers to be handing out drugs that are tested properly. Right now, dealers can get their supply tested at sites in the Downtown Eastside. The machine used in testing is the Fourier-transform infrared spectrometer, and it can detect multiple substances in minutes. We need more people who are trained to operate these machines. We also need to hire more drug users in harm-prevention roles, because they understand the impact of opioids.

How are you coping with the onslaught of another new drug?

I’m really numb to it now, because I’ve dealt with this so many times during my career. We constantly lose members of our community, people we care about. Most recently, I lost my older brother, who died from smoking contaminated crack. It really takes a toll on my mental health, so I spend time with friends, go for hikes and talk with a counsellor. I also run a drug-user group called the Coalition of Peers Dismantling the Drug War. We have to fight hard every day, because things are getting worse.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.