Why using social media might make you a better parent

Despite worries about distraction and oversharing, experts say good things happen online

Happy family using laptop together on bed at home in the bedroom. (Wavebreakmedia/Shutterstock)

Share

After Leigh Mouck’s son was born ten weeks early, she realized her new-parent struggles were on a different level from other moms. He spent two months in the neonatal intensive care unit and caused new worries after leaving the hospital.

“When [parents of premature babies] go home, we’re told, ‘Your kid must not get sick, so you really want to limit contact with other people,’” Mouck says. “The common experience for many of us is that we’re terrified to bring them anywhere.”

Many parents use social media to share cute moments or update faraway relatives, but Mouck found herself searching for individuals facing similar challenges.

“Even when I was starting to go out to other parent groups and baby groups, people ask you to share your birth story, and you tell it, but you just want someone else who gets it,” Mouck says. Answering a simple question about her son’s age required an explanation about “two birthdays”: one calculated from the day he was born, the other corrected to the date he was expected. “I was so emotionally overwhelmed … I was like, I need my people.”

So Mouck started a Facebook group for other Toronto parents of babies born prematurely, recruited members from other parenting groups in the city and set up a meet-up with moms in her own neighbourhood. “We all explained our birth story and there was so much ‘Yeah, that’s exactly what I felt,’” she says. “So it was really powerful.”

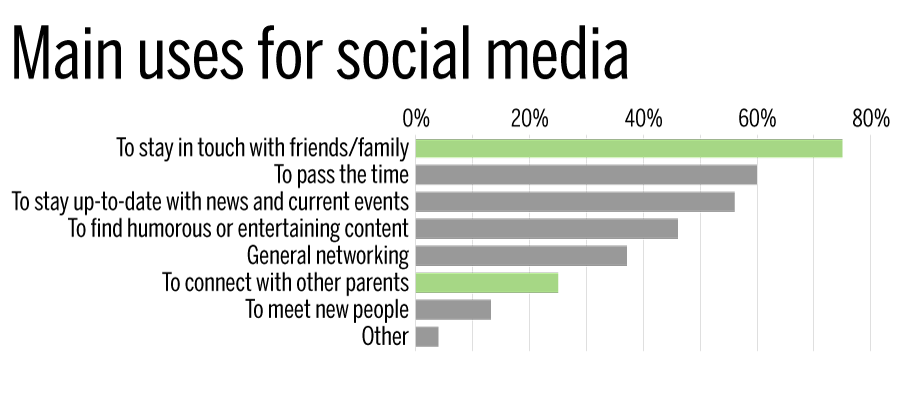

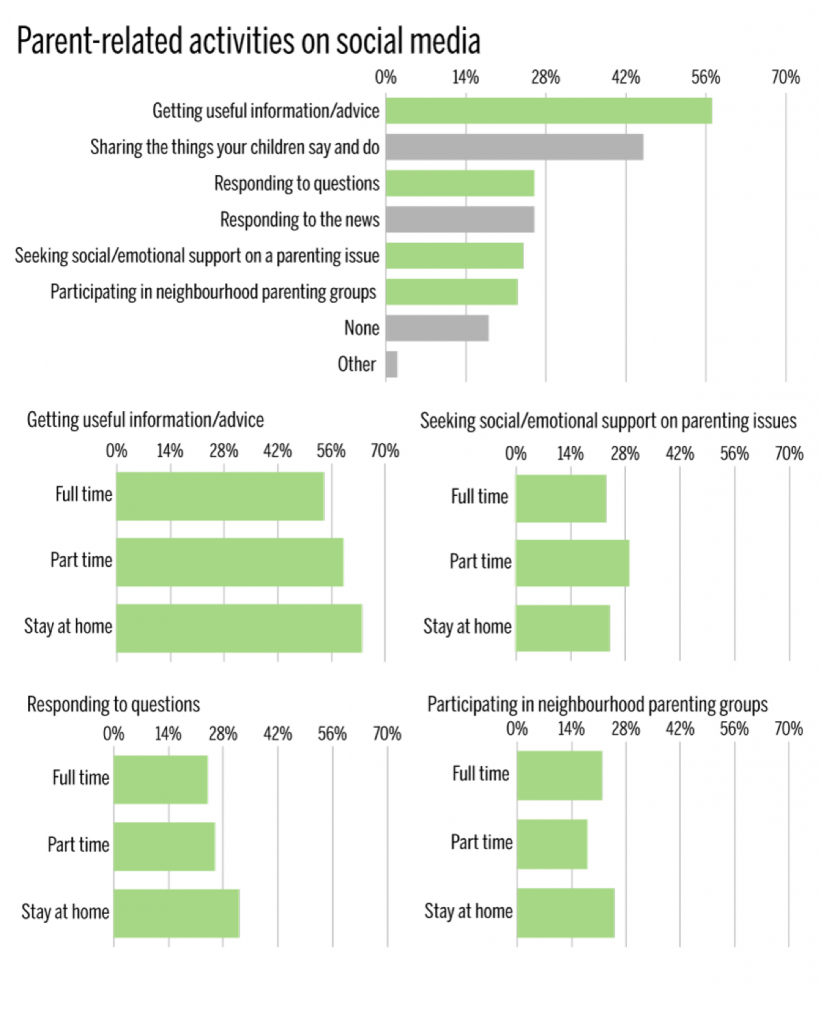

In an era when parents are often warned about the dangers of social media, Mouck’s experience demonstrates that online networks can also serve as powerful parenting tools. A 2017 survey conducted by Today’s Parent demonstrates the positive effects that Facebook, Instagram and other social networks have on the lives of mothers and fathers. There are legitimate concerns about over-sharing and distraction, but the data collected from 1,000 parents (most with children under the age of 10) suggests social media can actually help us be better caregivers. Nearly 60 per cent of parents said they use online platforms to find parenting information and advice, 82 per cent indicated social media helped stay connected with grandparents and 24 per cent noted they use it to seek emotional support for parenting issues.

Parenting expert Alyson Schafer says resources have come a long way since Dr. Spock’s Baby and Child Care was essentially the sole source of information. That means parents have many more options for finding out about different parenting philosophies and how to implement them. “If you’re a mom and you’re having trouble breastfeeding, talking to other moms and hearing their struggles—that’s so much more comforting than some expert saying, ‘Here’s how to have the perfect latch.’”

Edmonton mom CiCi Nguyen-Wong says tapping into that supportive community of parents was a surprising benefit of social media. She started an Instagram account specifically dedicated to her two-year-old twins, since they had become the main subjects of her photography. But she says the creative outlet turned into an important source of understanding and encouragement.

“It helps you feel less alone because being mostly a stay-at-home mom … you’re always by yourself and going through these struggles,” she says. “I know a lot of people think social media is really negative, but you make it what you make it. It can be a really big sense of community you’re missing out on.”

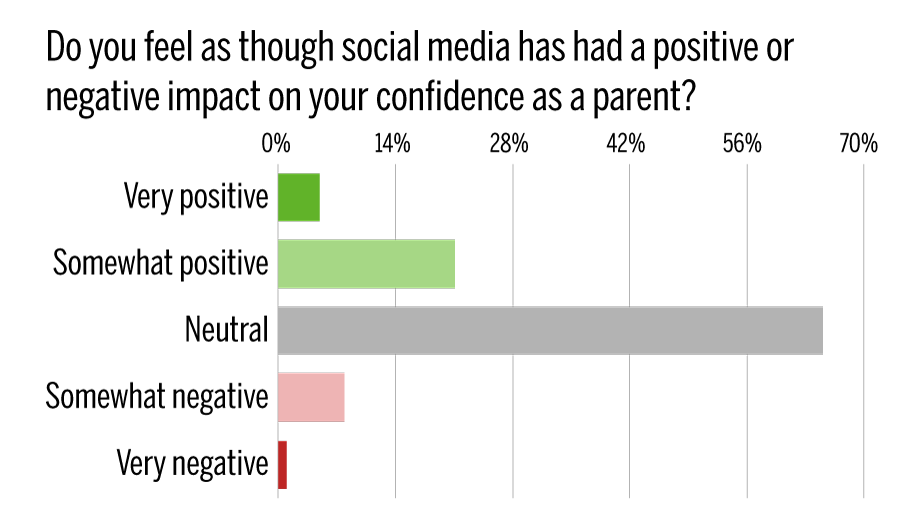

Indeed, parents are more likely to find community than criticism. The poll results suggest 73 per cent of parents have never felt judged by reactions to posts about their children. Twenty-six per cent, meanwhile, said social media had boosted their confidence as a parent with just nine per cent saying the platforms had a negative impact (The rest say social media hasn’t altered their level confidence for either good or ill).

While Schafer acknowledges the possible benefits, she also “constantly” hears about the pitfalls of social media during family counselling sessions. “For people with kids in the eight and older age group, it is their major pain point,” she says.

| Strongly Agree | Somewhat Agree | Somewhat Disagree | Strongly Disagree |

Social media allows grandparents to keep in touch by seeing posts and pictures of their grandchildren.

| 37% | 45% | 11% | 7% |

Social media is helpful for locating kid-friendly activities and/or connecting with other parents in my neighbourhood.

| 20% | 56% | 14% | 10% |

My friends share too much information about their children on social media.

| 25% | 44% | 23% | 9% |

Social media has been a lifeline to me for advice and support.

| 8% | 32% | 33% | 28% |

I have engaged in parenting-related debates on social media.

| 6% | 27% | 22% | 45% |

I have felt judged by online responses regarding posts about my parenting style and/or children.

| 6% | 21% | 26% | 47% |

I sometimes share too much information about my children on social media.

| 4% | 20% | 29% | 46% |

Schafer raises concerns about what parents are modelling when they frequently use their phones around their children from an early age. Forty-six per cent of parents in the survey said they use Facebook multiple times per day. “It’s about time well spent,” Schafer says. “When you’re child’s talking to you, are you able to put the phone down and listen to them?”

Eli Klein, the community and events manager for the online sharing and trading network Bunz, deals with people connecting on social media every day. As a parent, he also sees the potential pitfalls of combining the internet and children. Klein’s eight-year-old son recently got upset about a picture of him that his mom posted to social media, and she took it down. But 58 per cent of parents said they have never asked their child’s permission to post about them. And, intriguingly, while only 24 per cent of parents agree they overshare on social media, 69 per cent said their friends are guilty of oversharing.

Nguyen-Wong draws the line at posting nude photos of her kids online—much like 87 per cent of the people in the Today’s Parent survey—but she says she avoids judging parents who make different choices. And she has her own set of standards for what kinds of information she writes about her kids—keeping in mind that she posts for a public audience—and she monitors how often her sons see her using her phone.

Nguyen-Wong draws the line at posting nude photos of her kids online—much like 87 per cent of the people in the Today’s Parent survey—but she says she avoids judging parents who make different choices. And she has her own set of standards for what kinds of information she writes about her kids—keeping in mind that she posts for a public audience—and she monitors how often her sons see her using her phone.

Social media remains a useful parenting resource, Klein says, but as kids get older and establish their own identities, consent becomes an important part of the conversation. Both Mouck and Nguyen-Wong say they’re already thinking about how their children, who are still young, will use the internet when they get older. Making decisions about what how much to share about them online is now a necessary part of making decisions about how to parent.

“There are some lacking resources for parents in terms of understanding what sharing your children’s lives with the world means,” Klein says. “So many people participate about it without even thinking about it.”

Today’s Parent thanks Abacus Data, Canada’s leading public opinion and market research firm, for our survey on the social media habits of 1,000 Canadian parents. The survey was conducted online with 1,000 respondents between the ages of 18 and 45 in Canada who have at least one child under the age of 10 from August 29th to September 9th , 2016. The margin of error for a comparable probability-based random sample of the same size is +/- 3.1%, 19 times out of 20 for each province’s sample. The data were weighted according to census data to ensure that the sample matched Canada’s according to age, gender, and region. Responses may not add up to 100 due to rounding.