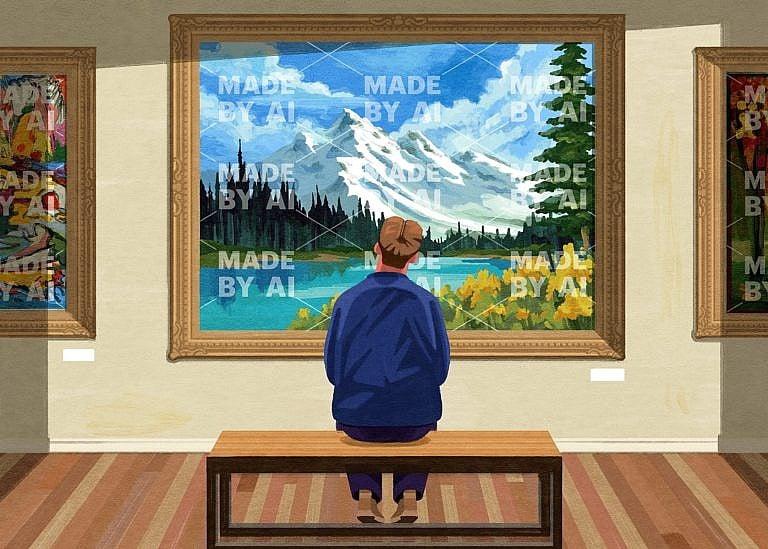

How can we tell whether content is made by AI or a human? Label it.

Generative AI tools like ChatGPT are now able to create text, speech, art and video as well as people can. We need to know who made what.

Share

Valérie Pisano is the president and CEO of Mila, a non-profit artificial intelligence research institute based in Montreal.

It used to be fairly easy to tell when a machine had a hand in creating something. Picture borders were visibly pixelated, the voice was slightly choppy or the whole thing just seemed robotic. OpenAI’s rollout of ChatGPT last fall pushed us past a point of no return: artificially intelligent tools had mastered human language. Within weeks, the chatbot amassed 100 million users and spawned competitors like Google’s Bard. All of a sudden, these applications are co-writing our emails, mimicking our speech and helping users create fake (but funny) photos. Soon, they will help Canadian workers in almost every sector summarize, organize and brainstorm. This tech doesn’t just allow people to communicate with each other, either. It communicates with us and, sometimes, better than us. Just as criminals counterfeit money, it’s now possible for generative AI tools to counterfeit people.

Mila, where I work, is a research institute that regularly convenes AI experts and specialists from different disciplines, particularly on the topic of governance. Even we didn’t expect this innovation to reach our everyday lives this quickly. At the moment, most countries don’t have any AI-focused regulations in place—no best practices for use and no clear penalties to prevent bad actors from using these tools to do harm. Lawmakers all over the world are scrambling. Earlier this year, ChatGPT was temporarily banned in Italy over privacy concerns. And China recently drafted regulations to mandate security assessments for any AI tool that generates text, images or code.

Here at home, scientists and corporate stakeholders have called for the federal government to expedite the Artificial Intelligence and Data Act, or AIDA, which was tabled by the Liberals in June of 2022. The Act, which is part of Bill C-27—a consumer privacy and data-protection law—includes guidelines for rollout of AI tools and fines for misuse. There’s just one problem: AIDA may not be in force until 2025. Legislation usually doesn’t move as fast as innovation. In this case, it needs to catch up quickly.

MORE: Ivan Zhang, Aidan Gomez & Nick Frosst are creating a smarter, friendlier chatbot

The European Union has taken the lead with its AI Act, the first AI-specific rules in the Western world, which it began drafting two years ago. Canada should consider adopting one of the EU’s key measures as soon as possible: that developers and companies must disclose when they use or promote content made by AI. Any photos produced using the text-to-image generator DALL-E 2 could come with watermarks, while audio files could come with a disclaimer from a chatbot—whatever makes it immediately clear to anyone seeing, hearing or otherwise engaging with the content that it was made with an assist from machines. As an example, a professor we work with at Mila lets his students use ChatGPT to compile literature reviews at the start of their papers—provided they make note of which parts are bot-generated. They’re also responsible for fact-checking the AI to make sure it didn’t cite any non-existent (or completely wacko) sources.

The EU’s AI Act includes a similar clause. Any company deploying generative AI tools like ChatGPT, in any capacity, will have to publish a summary of the copyrighted data used to train it. Say you’re using a bank’s financial planning service: in a properly labelled world, its bot would say, “I’ve looked at these specific sources. Based on that information, my program suggests three courses of action…” In the creative sector, artists have already filed copyright lawsuits alleging that their images have been lifted by bots. With mandatory labelling, it would be easier to run a check on what “inspired” those creations.

One of the main dangers of ChatGPT specifically is that it says incorrect things in such an authoritative way that it confuses us into thinking it’s smarter than it is. (A tweet from Sam Altman, OpenAI’s own CEO: “fun creative inspiration; great! reliance for factual queries; not such a good idea.”) The tool was trained on a massive body of information including books, articles and Wikipedia, and recent upgrades have allowed it to access the internet. That gives it the impression of having a kind of super-intelligence. And though the program generates its responses almost instantly, it blurts them out one sentence at a time, with a human-like cadence. Even people with highly developed intuition could be fooled; ChatGPT is designed to make us trust it.

What it’s not designed to do is find correct answers. ChatGPT isn’t a search engine, whose algorithms prioritize more credible websites. It’s common to ask generative AI questions and have it spit out errors or “hallucinations”—the tech term for the AI’s confidently delivered mistakes. On a recent 60 Minutes episode, James Manyika, a senior executive at Google, asked Bard to recommend books about inflation. Not one of its suggestions exists. If you type in “Valérie Pisano, AI, Montreal,” ChatGPT won’t offer a summary of my real bio, but an invented one. It’s already so easy to create fake news. Generative AI tools will be able to supply infinite amounts of disinformation.

RELATED: My students are using ChatGPT to write papers and answer exam questions—and I support it

In the absence of any meaningful guardrails, we’re having to rely on the judgment and good faith of regular internet users and businesses. This isn’t enough. Canada can’t leave oversight of this technology exclusively to the companies that are building it, which is essentially what happened with social media platforms like Facebook. (I’m no historian, but I recall that having some negative impacts on fair elections.) At some point, governments will either need to make it legal or illegal to pass off AI-generated content as human-created—at both the national and international levels.

We’ll also need to agree on penalties. Not every misapplication of generative AI carries the same level of risk. Using the art generator Midjourney to make a fake picture of Pope Francis in a puffy winter coat isn’t really a threat to anyone. That could easily be managed by a simple in-platform “report” button on Instagram. In areas like journalism and politics, however, using AI to mislead could be disastrous.

Labels also force a certain amount of AI literacy on the average person. We’re past the point of being able to say, “But I’m not a tech-y person!” Going forward, all internet users are going to be encountering AI on a daily basis, not just reading articles about it. It will inevitably change how everyone creates, competes, works, learns, governs, cheats and chats. Seeing (or hearing) a “machine-made” disclaimer presents us with the opportunity to choose how we allow its output to permeate our personal lives.

Of all the new tools, chatbots seem to have impressed the scientific community the most—specifically, because of how human they feel. (I actually find it difficult not to say “please” and “thank you” when I’m interacting with them, even though I know a bot won’t judge my manners.) So it’s easy to imagine using generative AI for tasks that are more emotional. But while I might ask Google Chrome’s new Compose AI extension to “write email requesting refund” to my airline, I probably wouldn’t use it to pen notes to my close friends. I can also see the upsides of Snapchat’s new My AI bot, which now greets millions of teens with a friendly “Hi, what’s up?” while understanding that a machine will never replace the deeper kind of support we need to grieve a difficult loss. Some things might be better left to humans. I guess we’ll see.