My students are using ChatGPT to write papers and exams—and I support it

“It made no sense to ban ChatGPT within the university. It was already being used by 100 million people.”

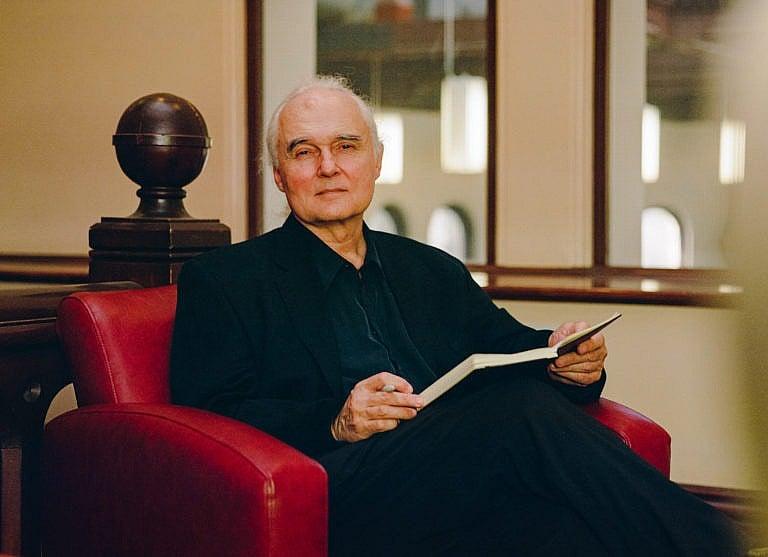

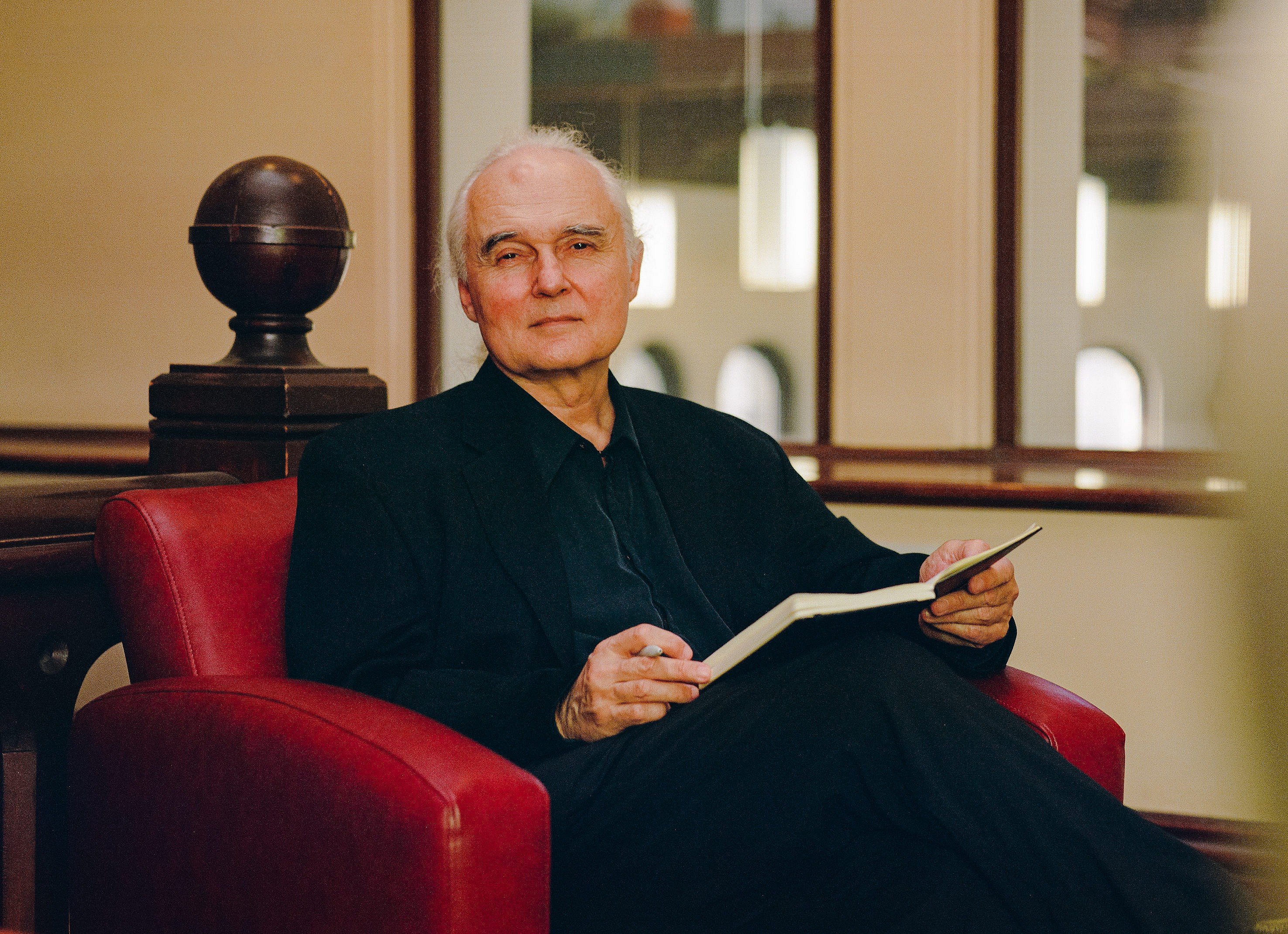

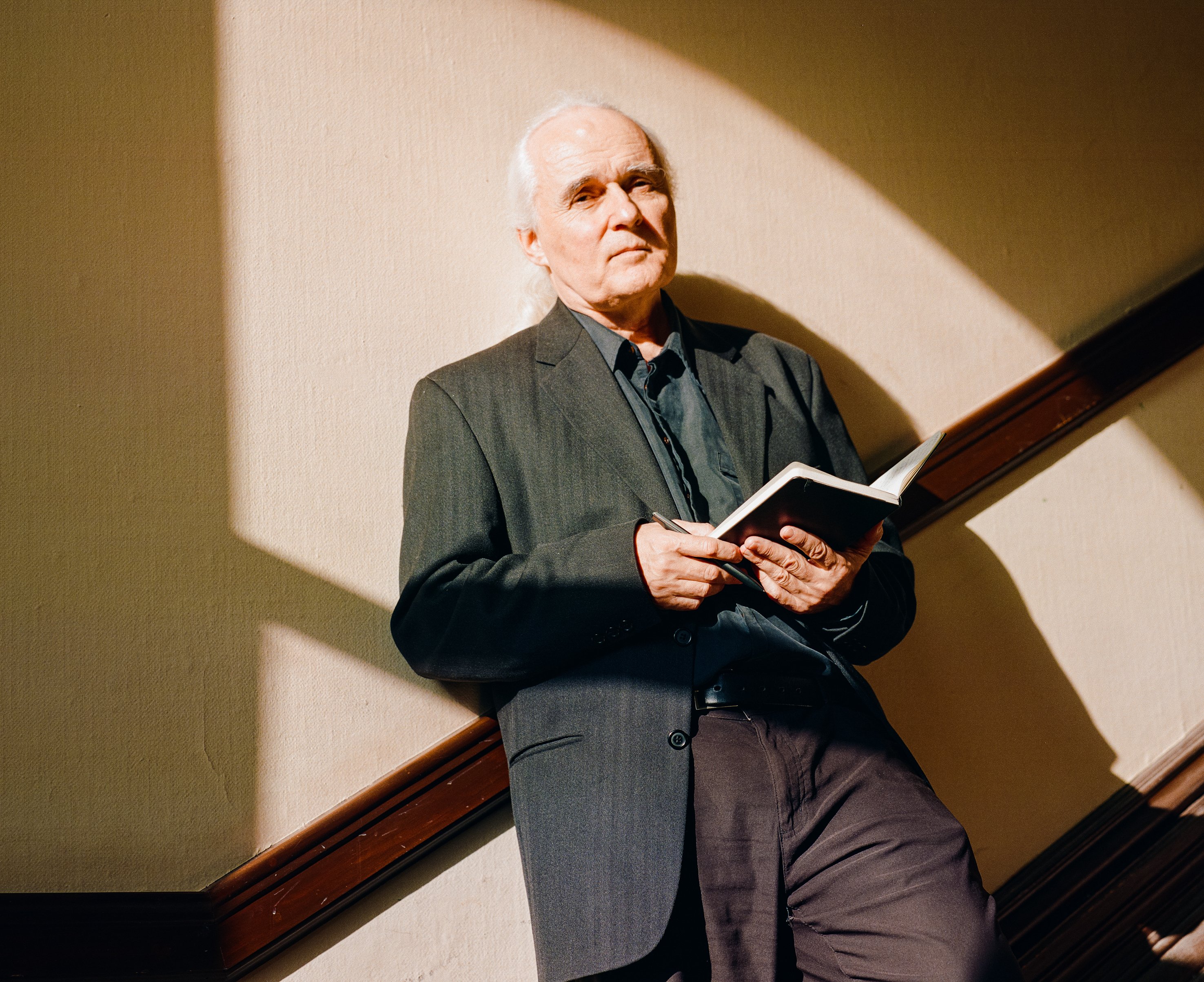

UofT biochemistry professor Boris Stiepe witnessed ChatGPT go from a curiosity to a phenomenon among students in a matter of weeks (Photos by Brent Gooden)

Share

I’ve been a professor in the University of Toronto’s biochemistry department since 2001. Last fall, I taught a first-year course on the foundations of computational biology, a field that applies computer-science principles to the study of biological processes. For the final assignment, I asked each of my 16 students to examine data on some genes involved in damage repair in human cells and write a short report on their findings. There was something off about two or three of the responses I received. They read like they’d been written by students who were sleep-deprived: a mix of credible English prose and non-sequiturs that missed the point of what I was asking. A few weeks earlier, the AI chatbot ChatGPT became available to the public, but it was so new that it never occurred to me that a student could be using it to help them with an assignment. I marked the reports and moved on.

READ: This U of T professor created an entire course on the Netflix mega-hit Squid Game

In the following weeks, I saw ChatGPT change from a curiosity into a phenomenon. It came up in every discussion I had with fellow faculty members, across all disciplines—from the humanities to data sciences. My colleagues wondered how one could tell whether a student used the AI to answer questions, and many were concerned with how it might enable plagiarism. What if a professor suspected a student had used ChatGPT but couldn’t prove it? A plagiarism allegation is no small thing: you can’t risk ruining a student’s academic career on a hunch. I thought again about that December assignment and realized those off-putting answers might have been my first brush with ChatGPT.

I directed the university’s bioinformatics and computational biology program for 15 years, and often wrote programs for my own lab, so I had been learning to “talk” to computers for years. I signed up for a ChatGPT account and became intensely interested in finding solutions to this new problem. I figured it made no sense to ban ChatGPT within the university; it was already being used by 100 million people. Over the Christmas break, it hit me: as professors, we shouldn’t be focusing our energy on punishing students who use ChatGPT, but instead reconfiguring our lesson plans to work on critical-thinking skills that can’t be outsourced to an AI. The ball is in our court: if an algorithm can pass our tests, what value are we providing?

MORE: How fraud artists are exploiting Canada’s international education boom

I became so consumed by the ChatGPT issue that I decided to spend the next semester pouring all of my energy into what I’ve called the “Sentient Syllabus Project.” With the help of colleagues across the world—a philosopher in Tokyo and a historian at Yale—I am creating a publicly available resource that will help educators teach students to use ChatGPT to expedite academic grunt work, like formatting an Excel spreadsheet or summarizing literature that exists on a topic, and focus on higher-level reasoning. The syllabus includes principles like, Create a course that an AI cannot pass, as well as practical advice on how to normalize honesty around AI use.

Instead of grading for skills an AI can manage, like eloquent language, we could grade on the quality of a student’s questions; how they weigh two sides of an issue and form an opinion; and, if they use ChatGPT, how they improve on the algorithm’s answer. This framework would change how I would have designed the assignment in December. Instead of asking students to read data and tell me what they see, I would say: tell me what you see, but also tell me how you came up with that answer. That type of question encourages a student to creatively engage with the facts—whether they receive them from ChatGPT or not.

ChatGPT offers many possibilities: this technology could help non-native English speakers put their ideas into coherent prose, or help people with atypical needs converse with a platform that won’t ever become impatient. It also opens up the option for personalized tutoring and customized assignments—education that would only have been available to the wealthiest few in the past. In general, this invention allows us to spend more time and energy on developing students’ critical-thinking abilities, which is a wonderful thing. However, this is not just about better teaching. Generative AI can already do so many things, all day long, without overtime, benefits or maternity leave. Our students must learn how to be better, how to create additional value for themselves and for others. They have to learn how to surpass the AI. And they’ll have to use the AI to do that.

We are entering a fascinating time in the history of AI, but I have two fears: one is that the adaptation moves so fast that it creates enormous economic disruption, which could cause people across industries—including some professors—to lose their jobs. The other fear is, of course, that we are not even sure what the adaptation could look like, or what new skills that we should be teaching in the meantime. For now, we need to accept that ChatGPT is part of our set of tools, kind of like the calculator and auto-correct, and encourage students to be open about its use. Then, it’s up to us as professors to provide an education that remains relevant as technology around us evolves at an alarming rate. If we outsource all our knowledge and thinking to algorithms, that might lead to an unfortunate poverty in our curiosity and creativity. We have to be wary of that.

—As told to Alex Cyr