I grew up behind the grills at Burger Baron, Canada’s weirdest fast-food franchise

How a failed McDonald’s knock-off became an anarchic, freewheeling fast-food success for generations of Lebanese-Canadian immigrants

Omar Mouallem (Photography by Amber Bracken/Back Road Productions)

Share

If you didn’t grow up in Alberta, you’ve probably never heard of Burger Baron. It’s a fast-food chain in only the loosest terms, with a menu that varies wildly from location to location. The branding? There is none in the traditional corporate sense, except for the words “Burger Baron” in each restaurant’s name. Some franchisees have pluralized it (Burger Barons), others eponymized it (Kelly’s Burger Baron) and others embellished it (Burger Baron Pizza & Steak). There have been nearly as many logos as locations—some, but not all, are reinterpretations of the original logo, a colourful little knight with crusader crosses in his shield. And the menus can run practically as long as a Chinese restaurant’s. Some of the Barons have actually sold Chinese food, or Greek, or Italian or Indigenous-inspired bannock burgers. The only guarantees are two burger recipes—the flagship Baron and the mushroom burger—their presence assured thanks to their sheer popularity with Albertans. Especially the mushroom, a curiously soupy sandwich that looks, and tastes, like Campbell’s Cream of Mushroom.

Actually, there’s one other guarantee: almost every single franchisee hails from a Lebanese family like mine.

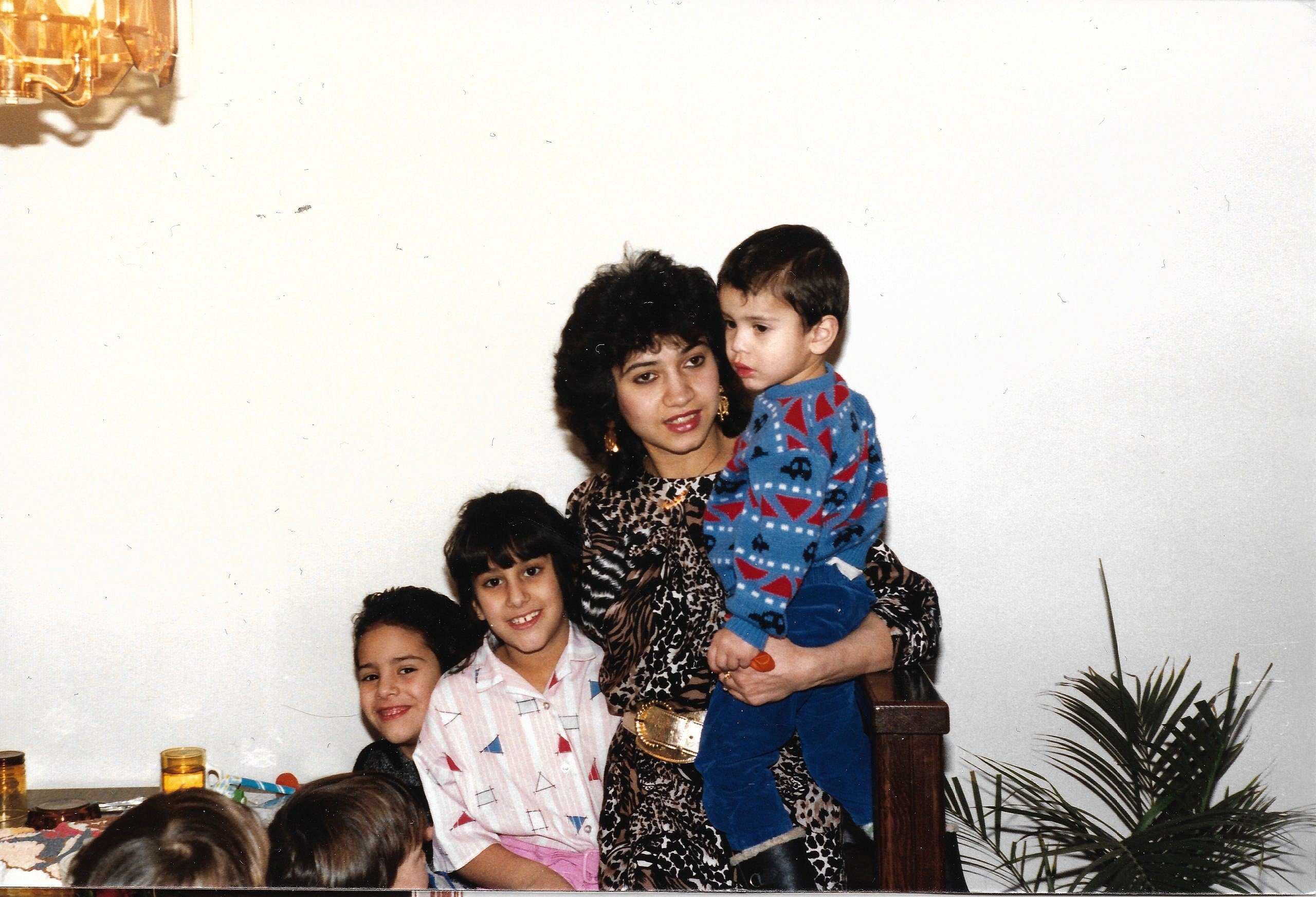

I was made a baron as an infant, when my parents—Ahmed and Tamam Mouallem—moved from Slave Lake, Alberta, to the even smaller town of High Prairie, four hours northwest of Edmonton, to open their franchise. They were shrewd Lebanese, who had left their country, once the Middle East’s capital of commerce, before it was destabilized by ethnic cleansing and sectarian violence. My dad’s uncle, living in Slave Lake, sponsored him to come to Canada in 1971, when Lebanon was teetering on the edge of civil war. By the time my dad returned home to find a bride in his hometown near the Syrian border, “Beirut” had already become synonymous with urban ruin.

As immigrants, they knew they were following in a proud tradition of Lebanese immigration to Alberta. Their predecessors—Lebanese peddlers, homesteaders, fur traders—had erected some of Canada’s first minarets and laid the groundwork for folks like my parents. And my parents, in turn, put a lot of work into leveraging and protecting that legacy, taking the model-minority trope straight to heart. They wanted their restaurant to be that restaurant-for-all-occasions that anchors every small town. And they wanted the townsfolk to know that even these brownfolk would sponsor the local hockey team and sign their boys up to play—and replace their son’s name on his jersey with the name of their business. At 12 years old, I was a skating billboard, “Burger Baron” emblazoned in lieu of my name on my extra-large yet too-tight jersey, for all of the five minutes I got on ice per game.

When my dad and I travelled from town to town for hockey games, he insisted we stop in at his counterparts’ businesses to meet franchise owners and reminisce/bitch about the homeland. It struck me as strange that all the Burger Baron owners were Lebs like us. Weirder still were the infinite incarnations of the chain. But despite its crapshoot reputation, my folks were tremendously proud of building a landmark in a community without many.

As I got older, I had mixed feelings about the restaurant, which seemed more like a prison at times. My relationship with it became even more complicated after I convinced my parents to pull me out of hockey—a request that backfired, because I was now expected to put extra time into the family business. I worked in the drive-thru and dish pit alongside my older brother Ali, who was being groomed more rigorously for succession on the grills. It calmed me to know that in Arab culture, the eldest son was the de facto steward of the family legacy. It was never in question who would inherit the throne; at most I’d been tapped as an understudy, in case tragedy should befall the future emir.

But I had more metropolitan ambitions. I wanted to be a filmmaker, which my parents lightly indulged by sending me to summer film camp in Red Deer and letting me work a cushy job at the local video store. I was only called into the restaurant when they were slammed, while Ali was expected to show up every day after school, and on most weekends. Once my brother could competently close the cash registers at night, my parents and I all sighed with relief. I started planning my escape, able finally to pursue my passions in peace.

In 2003, I moved from rural Alberta to downtown Vancouver to study film and writing, and later made my way back to my home province, to make a living at it in Edmonton. It was there that I began noticing people lighting up when they learned my family was part of a provincial institution. I was surprised to find a cult following for Burger Baron in the form of tattoos, a scene in the raucous comedy Fubar 2 and even a parody Twitter account: @Burger_Baron, known for trolling corporate fast-food chains. While the competition spends millions mastering reproduction, Burger Baron was the anti-chain, and people loved it. I was becoming prouder of being a baronet—not royalty, but evidence of the better life my parents had built for Ali and me.

I started investigating the chain’s origins 10 years ago as a magazine reporter, hoping to find the founder and thank him for what he gave to us. To my shock, he was not Lebanese. He was an American entrepreneur who moved his family to Calgary in 1957, with a plan to found the McDonald’s of the north. His name? McDonnell, Jack. But McDonnell had moved too aggressively on his expansion plans, and his company quickly burned up its forward momentum, leaving behind a trail of franchise owners orphaned by a bankrupted company. As far as anyone knows, the company’s intellectual property, like the name and logo, was never purchased by creditors or passed down to the next of kin. According to his son Terry McDonnell, Jack, who died in 1983, basically gave them all the recipes and wished them good luck.

They started to vanish quickly. By the mid-’60s, only a handful of Burger Barons remained, each independently owned and operated—sometimes even posted for sale in the classifieds. And who would ever want to buy a decentralized fast-food chain, with all the headaches of maintaining a brand and no corporate upside? The answer is Riad Kemaldean, a.k.a. “Uncle Rudy,” a.k.a. “the Godfather.” An astute businessman with a penchant for suits and cigars, Kemaldean bought his first Baron in Edmonton, in 1965. From its success, he sponsored friends and relatives from back home and set them up to manage new locations, which in turn became training grounds for his protégés’ own friends and relatives. The Burger Baron’s second wave spread through chain immigration, accelerating during Lebanon’s civil war from 1975 to 1990, and continues at a slower pace today. My dad apprenticed with his uncle, who bought one of the original Burger Barons from another Lebanese man, who had apprenticed with Rudy in the ’70s. Without royalties or start-up fees, the trade secrets proliferated through handshakes and favours, enduring every dining trend of the past five decades.

By the time I’d pieced together the puzzle, I’d grown fonder of Burger Baron and my family’s role in it. Like many second-generation kids, I struggled to see myself in Canadian culture, but being a Baronet makes me feel like I’m part of the fabric of Alberta—and, in a strange way, like I’m connected to the homeland.

***

In 2021, I began work on a documentary film: The Lebanese Burger Mafia. By the time I returned to High Prairie to film it, Ali had been running our parents’ Burger Baron for over a decade, doing things more or less the way our dad did—right down to sponsoring his son’s hockey team. Only he’d been doing it under a new, jazzier name: “The Boondocks Grill.” Another Burger Baron gone.

At its peak in the early ’90s, there were more than 50 completely independent locations, about twice as many as there are today. Burger Baron’s heyday is over, as owners struggle to compete amid the rise of big-box chains and foodie culture. The biggest challenge has been the next of kin, second-generation Lebanese-Canadians like me, who’ve become white-collar workers not in spite of Burger Baron’s success, but because of it.

And many of those who have remained in the business, like my brother, are eager to distance themselves from its outmoded reputation. I was quick to tease Ali for betraying our family legacy—renaming the place, renovating it to look more like a steakhouse, adding upmarket bison burgers and, interestingly, my mom’s fattouche salad recipe. But my real motivation was to find out whether he felt like his succession was a choice. Did my freedoms as the baby of the family make him resent his inheritance?

“A little bit,” he admitted. “I didn’t understand why you had these options. But with me, I was already groomed for it.” But Ali said those feelings were never stronger than the pride and satisfaction that came from running a small-town diner very well. “I’ve been able to provide for the family in a community that I love, that I grew up in. It’s what I know. I guess it’s what I love.”

Omar Mouallem is the director of The Lebanese Burger Mafia, playing in Toronto at Hot Docs on May 3 and 4, and in Edmonton on May 14. Burgerbaronmovie.com