Yayoi Kusama lets you taste infinity—so go ahead, take that selfie

Yayoi Kusama’s Instagram-ready mirrored rooms have made her an art superstar. But don’t be too quick—or snobby—in dismissing the selfie-seekers

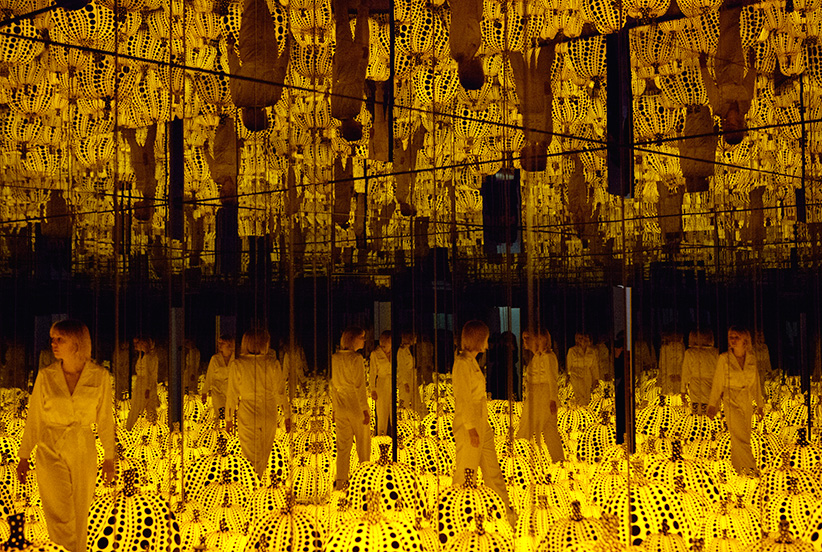

Inside the Yayoi Kusama exhibition at the AGO. (Photograph by Angela Lewis)

Share

Update (Nov. 1, 2018): The Art Gallery of Ontario has launched a month-long crowd-funding campaign to bring a permanent, original Yayoi Kusama infinity room to Toronto, which would be the first of its kind in Canada.

The exact reason that mathematician John Wallis first deployed the sideways figure 8 as shorthand notation for the mathematical concept of infinity has been lost to time. But there’s something elegant in the idea, all the same; by simply knocking it on its side, a number—with its clear boundaries and countable, tangible meaning—can be turned into something boundless and beyond comprehension. If humans can name and write ∞, maybe we can approach it and wrest it to the ground. This was the animating force of Romantic authors and artists, too, who used their limited canvases and chapbooks to interpret and expose the feeling of the sublime, found in the disorienting terror of facing the enormity of nature.

That idea—of the finite limits of how we think about infinity, and in trying to fathom something so vast that it might otherwise leave you insensate—resonates throughout the work of 88-year-old Japanese avant-garde artist Yayoi Kusama, whose Infinity Mirrors travelling retrospective, collecting works from more than six decades’ worth of various media, is making its lone Canadian stop from March 2 to May 27. In the small, finite mirrored rooms she’s best known for—participatory environments filled with firefly lights or groves of surreal objects, which are then refracted boundlessly around the two-to-three viewers permitted inside at a time, for 20 to 30 seconds—she is giving people the chance to have a sip of yawning infinity, without being consumed by it.

“It lets one feel the relativity of oneself within this vast universe and be able to be represented or even at peace with the insignificance of yourself in relation to the beauty of the universe,” says Mika Yoshitake, the Hirshhorn Museum associate curator who organized the touring exhibition.

It’s a heady exhibit tackling heady stuff—perhaps especially for a bold yet enigmatic artist who has been a superstar in her less-prominent field for decades, but whose public fame in recent years has been driven, at least partly, by social media, so often dismissed as artless vanity. Tens of thousands of people have had their finite patience tested by the AGO’s infinite-feeling lines, many of them just to snap selfies in the exhibit’s six rooms for the allotted 20 to 30 seconds amid these gorgeous, glittering expanses and Kusama’s Instagram-ready style, from a quirky grove of mushrooms to her trademark red polka dots. They’re the hottest tickets in town, and her rooms have bedazzled social-media feeds across the city.

Cue, then, the critics sniffily dismissing the selfie-hunters, a criticism that has followed the exhibit wherever it has gone as museums and galleries continue to grapple with questions about how they should evolve to retain contemporary relevance. Even Kusama herself has been criticized for her sin of making appealing-looking art, as if she could have envisioned social media in 2018 when first making these rooms in the 1960s; Roberta Smith of the New York Times wrote that she sometimes sees the octogenarian, who doesn’t herself use social media, as a “something of a charlatan” who “stoops to conquer with mirrored ‘Infinity’ rooms that attract hordes of selfie-seekers oblivious to her efforts on canvas.” And the Toronto Star’s Murray White, whose over-broad interpretation of Kusama’s “Narcissus Garden”—which tackled consumerism in the art world specifically—takes a swipe at some of Kusama’s audience: “The selfie-obsessed should take note: She’s not really on your side.”

“I think people do miss the point when people try to grab and capture because it’d be great to just put their phone down and experience the rooms in a very raw and direct setting,” says Yoshitake. “And you can’t capture that 3D immersive experience. It’s not just with your eyes—it’s with your bodily senses, too.”

Yes, the photo-mad do risk missing the forest for the polka-dotted trees: After all, her art depicts the psychotic hallucinations Kusama has endured since a childhood of abuse and neglect. “I felt as if I had begun to self-obliterate, to revolve in the infinity of endless time … and be reduced to nothingness,” she wrote in her 1975 manifesto Struggles and Wandering of My Soul, of the terror of losing yourself to infinity, akin to the Romantics’ approach to the sublime. Her work, then, is both a reflection and a response to her private terror, giving tangible form to her fears and receiving tangible, tethering comfort through her obsessive repetition of the forms in her rooms, sculptures and paintings—and without her practice, as she wrote in the Telegraph, she would have turned to suicide. They are her way of approaching the terrifying infinite that she glimpses in her psychotic breaks and, in making these anchoring items endlessly, she’s able to ground herself, re-appropriating the idea of death.

“Infinity is an impossible concept,” says Yoshitake. “And the flip side of infinity is mortality, and so her work is about confronting and overcoming that we as human beings are bound to die.”

The lights and objects in the rooms represent her anchors to reality as Kusama guides you along with her wary approach toward self-annihilation. Visitors can feel this, too; when you peer over the solid platform inside the dazzling The Souls of Millions of Light Years Away—dark and shadowy like a Death Star reactor shaft where gems have been frozen mid-air by the Force—your knees wobble and your stomach sinks, as the sides of your vision blur, your body is refracted across the mirrored planes, and you lose the certainty of where your skin ends and the art begins. In a way, taking out your camera to snap a selfie doesn’t feel like an act of ignorance—but a grasp at preservation. With a cell-phone photo, we’re fashioning our own hallucinogenic pumpkin.

So while distracting yourself from an attempt to replicate the transcendental feeling of infinity seems like a disservice to Kusama, clues abound in her work that she doesn’t mind that you find comfort in what you know—even if it’s in a selfie.

That act of grounding—finding something finite to anchor you amid infinity—is just as much a part of her work as the beauty of the infinite itself. In one mini-chamber as part of the Dots Obsession—Love Transformed Into Dots room, no matter how you torque your face to try to envelop your line of sight with the infinitely reflecting rows of hanging balls that look like dollops of pure mercury, you are unable to completely ensconce your eye past the rim of the hole, a physical border that grounds you. In Aftermath of Obliteration of Eternity (2009), where an analog cavalcade of firefly-like lights glow and fade, the visible seams connecting the panels of mirrors offer borders to infinity. The standout The Souls of Millions of Light Years Away (2013), where those seams blend in with the hanging lights, gets you the closest to obliteration, with the lights even shutting off completely during your stay—but flicker back to life, lest you feel totally expunged. In the rooms themselves, too, there are comforting reminders of the outside—the light hum of people milling about outside, a crack of the door behind you, the time limit itself, a possible stranger joining you in the room and, in the case of All the Eternal Love I Have for the Pumpkins, 2016, an AGO staffer accompanying you to make sure that no harm befalls the sallow squashes—and that’s all intentional, for Kusama. And in the participatory The Obliteration Room, a completely white and simply attired dining and living space that visitors wander through and erase, one dot sticker at a time, it is telling that the first dots that were centred around places and shapes that made logical sense: on the buttons of the radio, at the bottom of bowls, in a cross that materialized on a computer monitor. The human instinct for what is familiar and grounding is far too strong for even a taste of infinity to overcome.

Even her own explanation for her art suggests that it’s all about keeping hold of the finite when faced with infinity. Why else would she want to reflect her psychotic terrors if not to find a way to anchor herself? This is an artist who believes the act of creation, assisted by the mirrors’ infinite refraction, is an act of living, and so people careening images of her work across social media only helps her mission; our Instagram and Twitter and Facebook accounts become new kinds of mirrors, “in the vein of Kusama’s radical connectivity,” says Yoshitake. “That’s very much part of the expansion. She’s very happy that it’s touched many people.”

And so if infinity is death, and making art is deeply mortal, Kusama’s long art career creating unrelenting approximations of the infinite using finite tools—65 years of prolific output that continues to this day—is the ultimate act of confrontation, moored in the present, and saying to the infinite: not yet. In a way, that’s what the selfie-seekers are doing, too. By grounding themselves in the phones we spend hours with, and centring themselves in the frames, they are rejecting the lure and threat of obliteration and taking heart in the certainty of themselves.

“When you enter those rooms, there is a boundlessness, and people get a little scared at first, and then they’re able to ground themselves somehow, whether it be with a photo or looking at the ground or looking at the door open slightly and seeing the light filter through,” says Yoshitake. “I think it’s just human nature to try to ground oneself, and to be out of that comfort zone is also very exhilarating.”

For her part, Yoshitake doesn’t necessarily see the selfie as an act of grounding. And this isn’t to say that focussing all your energy inside the room on the perfect selfie, or deploying flash to shatter other people’s experience, or—worst of all—straight-up damaging the art doesn’t miss the point. Indeed, at the Hirshhorn, the exhibit had to be closed for three days after a visitor reportedly trampled on one of Kusama’s pumpkins in the pursuit of a selfie, and as some of the AGO exhibit’s first visitors milled around waiting to see Love Forever, 1966/1994, where two faces can peek into an octagonal mirrored box that refracts a festival of lights, one staffer mentions to another that someone had already knocked into it with a backpack, chipping a swatch of paint on the frame that serves as an entryway for a face to see and feel the Vegas-coloured lights’ propulsive heat.

But it seems that whether visitors lose themselves in the rooms—or instead tether themselves in their phone’s frame—Kusama’s message is that there’s power in getting to choose how close to infinity we want to get.

The next block of members’ tickets to Infinity Mirrors at the Art Gallery of Ontario will be available online on Mar. 20, while the next block of general-admission tickets will be available on Mar. 27.