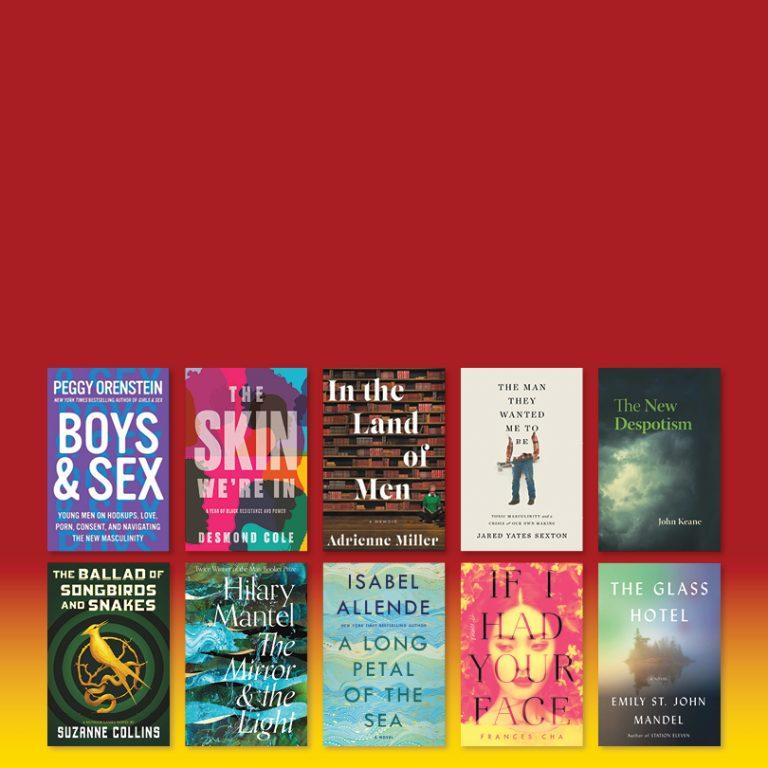

These are the books to watch in 2020

In 2020, books lose interest in Trump to instead focus on the changes that have reshaped our world (and ourselves)

Share

Perhaps it’s Trump Fatigue, although it’s more likely publishers and writers are holding fire until the American president’s fate becomes clear a year from now. Whatever the reason, 2020’s non-fiction will feature a Baby Blimp-sized hole where Trump used to dominate. That leaves breathing room for other contemporary issues, from the threats facing liberal democracy to modern society’s rapidly shifting concepts of what a man is or should be. The Man They Wanted Me to Be by Jared Yates Sexton and Peggy Orenstein’s Boys & Sex are liable to become two of the year’s most talked-about books.

An author and professor of writing at Georgia Southern University, Sexton, 38, is well-versed in the academic studies that detail the crises of American males; he especially focuses on “despair deaths” from suicide, alcohol and drug abuse. But he also dives deeply into his own past and the conflicting, repressive childhood messages that still roil within him: as a working-class boy in rural Indiana, Sexton could hear his stepfather sobbing alone in his room at night, the same stepfather who drilled into Jared that “boys don’t cry—crying’s for women.” The Man They Wanted Me to Be’s arresting mix of memoir, relentless self-examination and alarming social data expands the focus on toxic masculinity from the misogynist violence it unleashes to the damage it does to men themselves.

Orenstein, author of Girls & Sex (2014), examines the other half of the equation in Boys & Sex. She finds young men buffeted by the same cultural and media forces as girls—except for their greater immersion in porn—in the way they navigate new rules of physical and emotional intimacy. There are other takes on the same subject coming in 2020, including The War on Masculinity by British journalist James Innes-Smith, on why men and women really need to call a truce; Decoding Boys: New Science Behind the Subtle Art of Raising Sons by Cara Natterson, an American pediatrician and self-described “go-to puberty expert”; and an intense memoir, In the Land of Men. In it, Adrienne Miller writes about becoming Esquire magazine’s first female literary editor at age 25 in 1997, in a milieu dominated by “martinis, male egos, the unquestioned authority of kings,” and David Foster Wallace, who became both confidant and antagonist.

READ MORE: The first crop of #MeToo books reflect the movement’s complexity

Two 2020 titles, The New Despotism by political scientist John Keane, and journalist and historian Anne Applebaum’s Twilight of Democracy, express serious worry about the future of liberal democracy. Humans, as practical and opportunist as they are ideological, have an abiding love of authority, Applebaum argues, and of political systems that benefit true believers to the exclusion of everyone else. Keane’s focus is more on how states such as Russia and China have mobilized the language of democracy to win public support for governments based on patronage, economic growth, media and judicial control, surveillance and selective violence. But both writers also discuss authoritarianism’s appeal to the disaffected within democratic states, and the way its tendencies, language and style are seeping into our own culture.

There will be other topics discussed next year, to be sure; and, as always, other memoirs, including Chelsea Manning’s still untitled account of why she sent 720,000 classified U.S. military documents to WikiLeaks. There is much of the personal too in The Skin We’re In, journalist Desmond Cole’s fiery chronicle of a single year—2017—in the struggle against racism in Canada. Daniel Levitin, McGill University professor emeritus and Renaissance man—cognitive psychologist, neuroscientist, writer, musician and record producer—saw his 2006 book, This Is Your Brain on Music, spend more than a year on bestseller lists. Now, in Successful Aging—a 2020 release more hopeful than most—Levitin offers a new concept of aging and surprising research into how to make the most of it, welcome news in a steadily greying world.

While non-fiction reflects current issues as a matter of course, fiction is always all over the map, literally and figuratively. And 2020 is shaping up as a banner year for that truism, given new works from such genre-benders as David Mitchell and Emily St. John Mandel. Even so, fiction is always read with the political shadows of the day hanging over it, especially when the times are politically volatile—an understatement for our own day. And with Donald Trump (thankfully, if temporarily) sidelined for now, it is Brexit’s turn to loom over literature.

There is no more hotly awaited 2020 novel—given that the mythical beast known as The Winds of Winter, the sixth novel in George R.R. Martin’s Game of Thrones saga, shows no signs of assuming corporeality—than The Mirror & the Light, the concluding volume in British author Hilary Mantel’s Thomas Cromwell trilogy. Mantel, who won the Booker Prize for both of her earlier volumes, Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies, has been at her saga for 14 years, long before Brexit was a gleam in Boris Johnson’s eye. But still: a storyline focused on the twists and turns of England trying to figure out how to separate itself from a Europe-spanning transnational power, plotted against a fractious Parliament, with accusations of treason and prophecies of civil war, and the whipsaw rise and (metaphorical) beheading of prominent political figures—say, David Cameron, Theresa May and (just maybe) Prime Minister Johnson—could very easily be set in the early 21st century.

Mantel, of course, is actually writing about the 16th century. Her subjects are King Henry VIII and his insanely complicated marital life, England’s break with the Roman Catholic Church, and the blacksmith’s son who rose to be Henry’s chief minister before his fall from grace. Mantel opens The Mirror & the Light with the not-at-all-metaphorical decapitation of Queen Anne Boleyn, Henry’s second wife—an event largely engineered by Cromwell, then at the height of his power—and ends with his own beheading four years later, on the day Henry married his sixth and final wife. But the English Reformation was secure, even if the revolution, as usual, had eaten its own children. Another Brexit echo, perhaps.

There are newcomers in fiction to keep an eye on too, including Frances Cha. Her If I Had Your Face, about four young women barely surviving a world of frozen social hierarchies, extreme plastic surgery and K-pop madness in contemporary Seoul, is arriving with considerable advance praise. Actor Jim Carrey’s debut novel, Memoirs and Misinformation, does its own genre mash-up in a story of Hollywood, celebrity and growing up in Canada, “none of [it] real and all of it true,” according to the author.

Other writers are building on past breakthrough works. Station Eleven, Canadian Emily St. John Mandel’s novel of a theatrical troupe in the years after an epidemic destroyed most of humanity, blended mystery, science fiction and a low-key literary style to make it one of the most noteworthy books of 2014. Now, in The Glass Hotel, St. John Mandel moves from a five-star hotel on the northernmost tip of Vancouver Island through Manhattan to a container ship off the coast of Mauritania in a story about greed, ghosts and guilt.

Nor is Hilary Mantel the only world-famous author to see print in 2020, although one of those big names is not the novelist’s own. The Italian writer who goes by the pseudonym Elena Ferrante came to fame with the Neapolitan Novels (2012 to 2015), four books that chronicle the lifetime friendship of two remarkably perceptive women from the wrong side of Naples. The Lying Life of Adults is a delightful surprise for fans, many of whom feared that Ferrante, who is assumed to be in her 70s by the novels’ autobiographical clues, might never publish again. Instead, they have one of the most subtly nuanced writers alive returning, in a story of a young woman struggling to make the transition to adulthood, to her exquisite explorations of identity, women’s lives and Naples itself.

Back, too, is Suzanne Collins, whose YA trilogy The Hunger Games—a savage take on the Iraq war and reality TV that saw teenagers slaughtering each other on live television—sold more than 60 million copies and spun off four hit movies. The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes, Collins’s first foray into her Panem dystopia in a decade, is a prequel set 64 years before the original trilogy. The 20th novel by the celebrated Chilean-American writer Isabel Allende will also appear in English translation. A Long Petal of the Sea, which traces the Chilean afterlife of two refugees from the Spanish Civil War, opens in 1939. The Certainties by Canadian Aislinn Hunter, author of the prize-winning The World Before Us, opens in the same country a year later. This time the refugees are pouring into Spain, from a France overrun by Nazis. One of them sees a Spanish girl named Pia, who decades later encounters yet another migrant crisis.

Then there’s David Mitchell, whose seven novels—especially Cloud Atlas, a genre-bending work that circled from 19th-century New Zealand to a post-apocalyptic Hawaii and back—have cemented his reputation as one of the most innovative writers in English literature. His new Utopia Avenue, about a ’60s British rock band and its fateful American tour, will feature—like all Mitchell novels—stories within stories, recurring characters from his other books and the trademark virtuosity that might let him meet his ambition for Utopia: to write about what Mitchell calls the “word-less mysteries of music.”

This article appears in print in the January 2020 issue of Maclean’s magazine with the headline, “Turning a new page.” Order a copy of the Year Ahead special issue here. Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here.