Why the rich drop millions on Damien Hirst

Maclean’s reviews The Supermodel and the Brillo Box

DOHA, QATAR – OCTOBER 09: Visitors observe Damien Hirst’s ‘The immortal’ at the Relics Exhibition by Damien Hirst at Al Riwaq space next to Doha’s Museum of Islamic Art on October 9, 2013 in Doha, Qatar (Photo by Niccolo Guasti/Getty Images)

Share

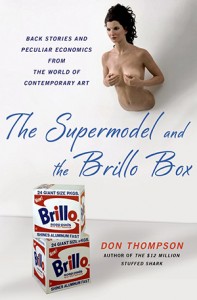

THE SUPERMODEL AND THE BRILLO BOX: BACK STORIES AND PECULIAR ECONOMICS FROM THE WORLD OF CONTEMPORARY ART

THE SUPERMODEL AND THE BRILLO BOX: BACK STORIES AND PECULIAR ECONOMICS FROM THE WORLD OF CONTEMPORARY ART

Don Thompson

What makes this wonderfully informative book, which could well have been subtitled Adventures Among the One Per Cent, such a pleasure for the rest of us to read is the author’s own peculiar backstory. Thompson is not only an aficionado of contemporary art, he’s an economist, a professor of marketing and strategy at Toronto’s York University. He can thus persuasively set out all the reasons, from aesthetic appreciation to personal aggrandizement, why someone—whether Qatari royal or Western hedge-fund manager—would pay $12 million for a stuffed shark (the subject of Thompson’s last book).

This time around, Thompson deserves full marks simply for his deft rendering of artist Eric Fischl’s domestic pet explanation of the mysteries of contemporary art. Call over your dog, and his response—ears perked, head in your lap, eyes focused on yours—is “linear” and easily understood. Try that with the cat. If she comes at all, it will be via a circuitous route and she will end up with her rear end facing you. Any attempt to understand requires wrestling with “non-linear, indirect, complex, alien” communication: “art is a cat.” But Thompson gets bonus points for illuminating the signature facial expression—puzzled, somewhat aggrieved—of contemporary artists. For them, their work is straightforward: “To the artist, contemporary art is a dog.”

After that, the art and its eye-popping markets start to make sense. Art is now what a recognized artist says is art, meaning (among other things) that a civilian wouldn’t get far peddling a stuffed fish for $12 million, but a brand-name artist, like shark creator Damien Hirst, is limited only by his imagination. Back story is crucial: Elizabeth Taylor’s jewellery sold at auction for 10 times its replacement value precisely because it was once hers. As much as the art itself, as Thompson points out, buyers spend millions for the right to tell a story about it. There are signs, in fact, that the backstory could eclipse brand as a value marker under certain circumstances.

Consider Sotheby’s London sale of Bridge No. 114 in November 2011. It was described in the auction catalogue as the work of abstract expressionist painter Nat Tate, a one-time lover of Peggy Guggenheim who destroyed most of his work before killing himself by jumping off the Staten Island ferry. It sold for $11,200 to a telephone bidder in Australia, well in excess of the pre-sale estimate of $4,600 to $7,700. Except that the artist is a character from William Boyd’s novel Any Human Heart, his name derived from “National Gallery” and “Tate Modern,” and Boyd created the painting. Sotheby’s was in on the deception, donating the proceeds to the Artists’ General Benevolent Institution. Yet, the buyer did not demand the sale be voided. And why should he? With a backstory like that, “Tate’s” painting can only grow in value.