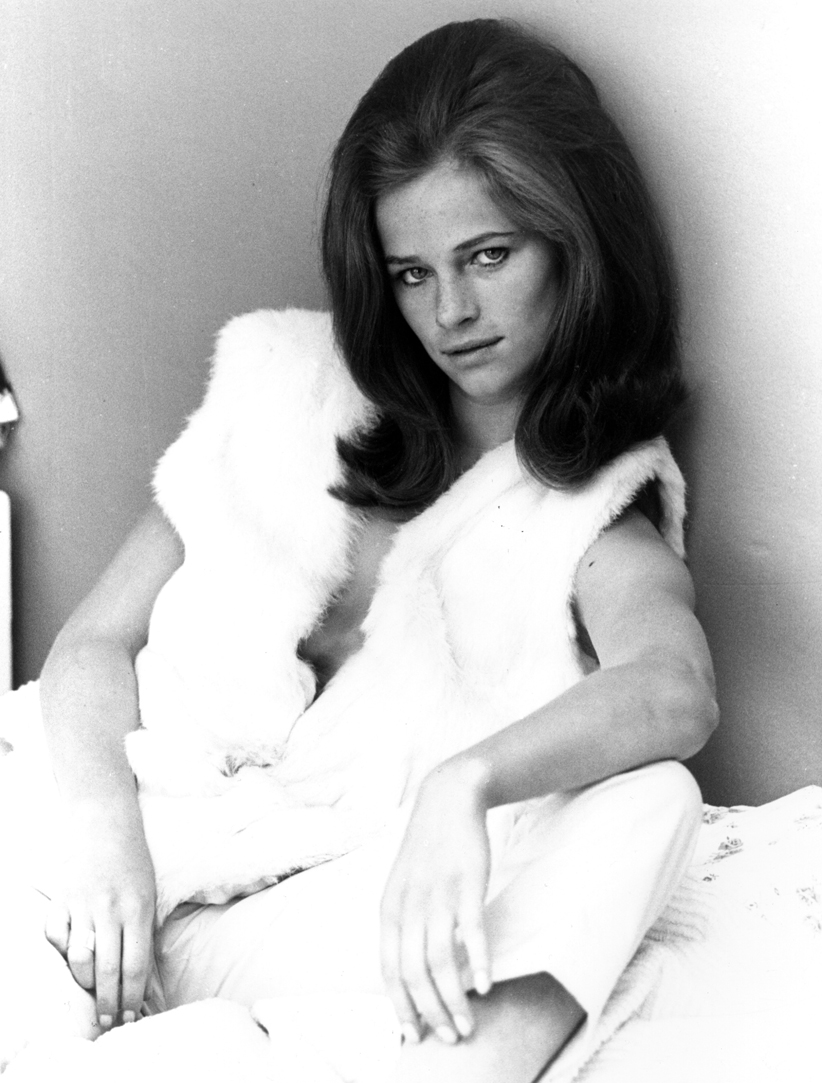

Charlotte Rampling: A ’60s icon’s non-comeback

The actress and icon on Hollywood ageism, the silliness of stylists, and why she loves Sylvia Plath

Share

At the age of 69, actress Charlotte Rampling has been able to keep her street cred intact in both the film industry and the theatre. She’s worked with cinematic masters such as Luchino Visconti and Woody Allen, and is brave enough to bring Sylvia Plath’s poetry to life on stage (a performance that headlines at Toronto’s Luminato festival next week). Her CV, which remains Disney-free even in her later years, testifies to her resistance to all that is Hollywood. Her big break came in 1974, when she appeared in the controversial art house film The Night Porter. Rampling portrayed a concentration camp survivor caught up in a sadomasochistic relationship with a former Nazi officer, played by Dirk Bogarde.

The film spurred her attraction to unconventional roles. Her non-conformist choices have clearly done well by her: Rampling is starring in seven films this year alone (and there is her regular stint on ITV’s Broadchurch). In a career-spanning interview, Rampling opens up about her celebrated past, her unconventional script choices and the problems she sees with casting today.

Q: What is it about Sylvia Plath’s work that connects you to her?

A: I’m most connected to the deep daring of her voice. I’m interested in how far she goes and how uncompromisingly she expresses what she really does feel.

Q: Many successful performers today feel that, as [they] get older, performing gets more daunting; they fear one bad job could undo years of great work. Do you ever feel as though stepping onstage might tarnish the legacy?

A: No. It keeps getting easier for me. You don’t care so much in the end. You care less about what people think and less about the impact you are maybe, or maybe not, making. When you get into your 60s, you know your time is limited. When you’re younger, you think, “Oh, I’ll do it better next time,” or, “I’ll take more time to get it right”—no. Now, you have no time. That gives everything a fantastically beautiful and edgy urgency.

Q: You became the face of NARS cosmetics last year. Joni Mitchell, Cher, Joan Didion, Helen Mirren and Jessica Lange have all gone on to be models for fashion and beauty companies. Is there a benefit to having an experienced or mature model be a spokesmodel?

A: The 18-year-olds with their extraordinary beauty, who are the usual faces of these sorts of things, quickly become something else. We all need to have role models for when we do get older . . . for when you don’t have that same kind of youthful beauty. This is an intelligent approach these companies have finally taken. As if it’s so daring to put an older woman in a campaign! It doesn’t make sense in marketing terms, if you put these teen beauties in the ads. They aren’t the ones who are going to buy it! They don’t need it!

Q: Maggie Gyllenhaal recently stated that, at the age of 37, she was not considered for a film role because she was told she was too old to play the love interest of a 55-year-old man. Will this sort of sexism ever been obliterated?

A: There’s a whole body and lobby of people behind it [who] will absolutely not want it to be changed. Usually, this is only for financial reasons. The powers that be will make audiences believe things that are ridiculous. Things like, “An older man is not going to go for a 37-year-old. Why should he? He’s going to go for a 25-year-old.” It is just pathetic.

Q: The whole red-carpet system—which is built on stylists dressing celebrities—has changed the way we perceive actresses altogether. Sophia Loren once said of stylists: “Having someone dictate how you look can be like surrendering your soul to them.” Do you agree?

A: Of course! Well, the dress is always mentioned first, nowadays. People don’t even mention the actress or her work. Those actresses [often look] quite ridiculous; actresses aren’t models, so they don’t look great in fancy clothes. They’d be better off wearing things that would suit their personality.

Q: Do you think the idea of being a brand clouds the artistry that comes with being an actor or actress?

A: They are depersonalized by all this branding and brand association. Nowadays, many think that if you don’t have a brand, you don’t have an identity. Quite the opposite, I’m sure of that.

Q: You’ve worked with Visconti and Allen. Tell me about the differences in their process. Was it like chalk and cheese?

A: Ha! Yes, of course it was. I can’t see any similarities whatsoever. Visconti was a grand man, and he had this court all around him and had such a wicked sense of humour. I was 23 at the time, and hadn’t had much experience, but I was playing a woman who was a lot older. He said, “I will dress you in the most beautiful clothes, right down to lingerie”—which was made for us in the 1930s style. If he didn’t have all the details in place, he would not begin filming. Everything had to be real and authentic! Even things that were hidden, like, in drawers, they’d have all the beautiful linen sheets and the cutlery. He didn’t even see them, but he had to have them. That’s where he came from. That was his world. He did tell me, “I can put you in the most beautiful clothes and sets, but I can’t then perform for me. But you will perform for me!” Back then, there [were] no monitors, so he would always make sure I knew where he was. There was something so beautiful in that passage, because he was such an impressive man.

Q: Woody Allen is known to use triggers to relax his cast. What did he do for you?

A: Stardust Memories was when he left Diane Keaton and he hadn’t started with Mia Farrow, so we had this platonic love affair. He adored me! He asked a lot of questions and did magic tricks for me—mostly card tricks and illusion tricks, hand magic. Making things disappear. There was great sweetness between the two of us. We were rather like children. It would have been lovely if [Allen and Visconti] could have had a conversation. They both would have loved it.

Q: One of the most acclaimed performances in your career was in The Night Porter. Looking back to that, what would you say were your most difficult scenes?

A: Most of them. It was never a question of getting it right, so to speak. How can you know what a concentration-camp survivor would be like? How would you survive anyway in a situation like that? I had nothing to go by, so I just went with my gut. I threw myself into that role and I had Dirk Bogarde who had been there and had some of those experiences—obviously, not on the Nazi side.

Q: Do you feel that trusting yourself has always served you well?

A: It’s led me through my life. It should lead people more. Most of the time, we have the answers in us, but we don’t dare listen. We often think that the cleverness in our heads is better than our inner instincts. I’ve always had that innate confidence.

Q: Lana Del Rey has often cited your early looks as an inspiration for various photo shoots she’s been in. Do you see the connection?

A: No. It never occurred to me. I’m moved by it, but there’s something troubling about it also. I never wanted to be like anybody and I didn’t want to emulate anyone. Lana Del Rey must go her own way; she mustn’t try to emulate something. The world we live in is very different than the one I grew up in. People do tend to take on other people’s identity.

Q: Through the years, you’ve been outspoken about various injustices. Do you feel actors and actresses today are afraid to be as outspoken?

A: You aren’t allowed to be. Media training has been [around] a long time, but not as full-on as it is now. I have been resolutely independent and I have always done it my own way. We’ve only got one life and I’d like to live it. If it all gets rocky, at least I’m following a path and not compromising. I’m being like Sylvia Plath. Although she was only 30, as is the case with artists who die young, she seemed relatively old.

Q: What lines from this project would you consider to be the most potent?

A: I remember all 12 poems, but there’s one line that just jumped into my brain: It is a terrible thing to be so open: it is as if my heart put on a face and walked into the world.’ That’s part of her poems about maternity, and they are so violent. That’s a tender, touching one of [hers].

Q: What are you most excited about in the coming months?

A: A film called 45 Years, [for] which I won the Best Actress prize with my partner, Tom Courtenay, at the Berlin Film Festival. It’s so impressive when you see so many people seem to “get it.” It’s going to now screen worldwide, and it was bought in hundreds of countries. It will start its journey in August.

Q: Are you looking for something you haven’t done? Is there a script you’ve been hankering to be a part of?

A: I’m always looking, but don’t know what that is. Not to say that I’ve done everything! It’s got to have a particular Rampling thing about it so that it’s worth me doing.

Q: Your place in a film never feels like it’s part of a Hollywood tradition.

A: It doesn’t work for me. I didn’t feel like I belonged in these entertainment-like films. I needed to find a way of expressing myself in cinema in a different way.[Otherwise], I’m going to get bored and irritated.

Q: Every couple of years, your name and the word “comeback” seem to make it into the mainstream press. Is it an offensive word?

A: I don’t like it at all. I think it sucks. I’m working away for years on a lot of experimental things with artists, but it’s mostly undercover. Then it will pop up and people will say, “Oh, she’s back again!” It’s like when I see the odd taxi driver and they’ll say, “Haven’t seen you around much, not working anymore, eh?” I would never say that to anyone. It’s insulting.

Q: Was there a point in your career when you felt a deep shift happen with the way you did your job?

A: When I stopped caring about what people thought! You’ll get there. In your 60s. You gotta get old to get there!