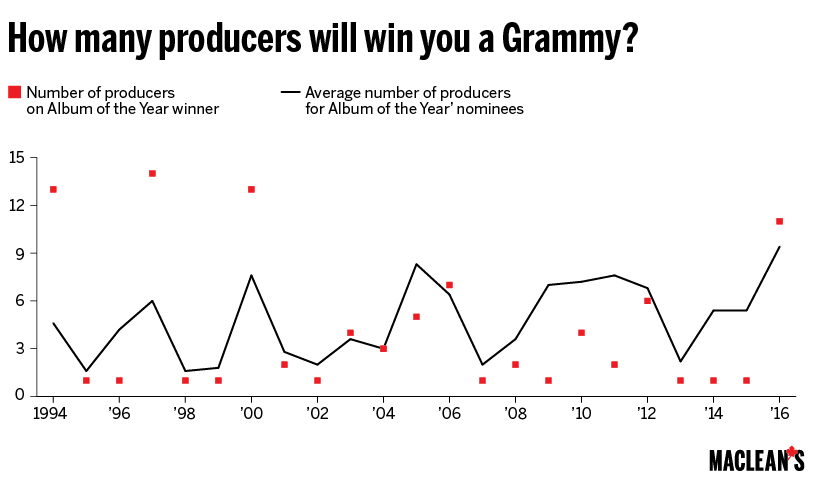

Does it really take 11 producers to win a Grammy?

Producer inflation may be a huge trend in music, but to win a Grammy, it seems you need to go the opposite way

Taylor Swift performs at the 58th annual Grammy Awards on Monday, Feb. 15, 2016, in Los Angeles. (Photo by Matt Sayles/Invision/AP)

Share

Last week the Grammy Awards named Taylor Swift’s 1989 the Album of the Year. That particular award goes to the producer of the album—or, as is increasingly the case, producers, plural: 1989 boasted no fewer than 11 people taking credit for its success. That may seem like a lot of cooks in the kitchen, but some of Swift’s fellow nominees would disagree: Kendrick Lamar had 17 people credited as producers on critical favourite To Pimp a Butterfly, and Toronto’s The Weeknd had 15 on his breakthrough, Beauty Behind the Madness.

Related: How the 2016 Grammys took one step forward, three steps back

Those numbers are not an anomaly for a modern pop album, which often appear to be made by committee: just look at the most recent records by Rihanna (21 producers) and Justin Bieber (19 producers). Twenty years ago, blockbuster albums regardless of genre usually had no more than three producers: in 1995-96, bestselling records by Hootie and the Blowfish and Alanis Morissette—even the Waiting to Exhale soundtrack—all had only one producer. The one hip-hop album to ever win Album of the Year, in 1999, was credited solely to one producer: the artist herself, Lauryn Hill. In 2010, Taylor Swift only needed four producers to shepherd her album Fearless to a Grammy. Likewise, the first two times Eminem was up for Album of the Year, in 2001 and 2003, he had only five producers; in 2011 he had 16.

In the age of streaming and shuffle, few people sit down and listen to a full album anymore anyway—so who cares if it sounds like a dog’s breakfast? Grammy voters do. Notoriously conservative, as proven by Beck’s (self-produced) triumph over Beyoncé (13 producers) in 2015—they prefer albums meant to be consumed as a full listening experience, not a series of singles. And most Grammy winners keep it lean, even lately: everyone from Arcade Fire to Daft Punk, Herbie Hancock to the Dixie Chicks, have no more than two producers—and that’s counting the artists themselves as credited producers.

In fact, in the 48-year history of the awards, Swift’s 1989 becomes only the third non-compilation album credited to more than 10 producers to win Album of the Year. The first was Celine Dion’s Falling Into You in 1997 (14 producers); the second was Santana’s Supernatural in 2000 (13 producers).

Even having more than three producers on a Grammy-winning album is unusual: it’s only happened five other times, and all since 2003 (Adele, U2, Ray Charles, Norah Jones—and Swift’s Fearless). Before Mariah Carey’s 1991 nomination for her self-titled debut (with seven producers), you’d be hard pressed to even find an Album of the Year nominee with more than three people at the helm—though two Album-of-the-Year-winning soundtracks, Saturday Night Fever and The Bodyguard, were credited to 14 and 13 producers, respectively.

It’s a producer’s job to shape the sound of the music, decide on arrangements and which performance is best. Increasingly in pop and hip hop, the producer also makes the beats and writes the hook, leaving the lyrics up to the singer or rapper. A producer like Max Martin is considered essential to a hit record: since he broke through writing for the Backstreet Boys 20 years ago, he’s penned massive hits for Britney Spears, Kelly Clarkson, Katy Perry, Taylor Swift, Ariana Grande and Adele. Any aspiring pop star would be wise to blow their budget hiring Martin for one song—which is exactly what The Weeknd did (“Can’t Feel My Face”), and it worked. (The Weeknd also employed songwriter-producer Stephan Moccio, the Canadian behind huge hits for Céline Dion, Miley Cyrus and Nikki Yanofsky.)

In a music business that’s bleeding money, almost every pop album is a potpourri of the best talent money can buy, in pursuit of a hit song. 2015’s biggest song, Drake’s “Hotline Bling,” wasn’t attached to any album or accompanying marketing strategy. And it’s a myth that only pop, R&B and hip hop pile on the producers. Hit-hungry chart-chasers like Coldplay or late-period U2 also employ multiple pop producers to make themselves seem relevant.

As technology evolves and the very definition of a song has been redefined, how a song sounds is just as—if not more—important than its melody or chords. Which is why the roles of producers and songwriters have been conflated. In that sense, modern pop records are no different in their construction from the age-old model of Nashville or Motown or the Brill Building: throwing a bunch of songwriters together in an office and cherry-picking the best results for a star artist’s album.

The Grammys may reward parsimony. But everywhere else in the world—as Taylor Swift will be the first to tell you—a star needs a squad.