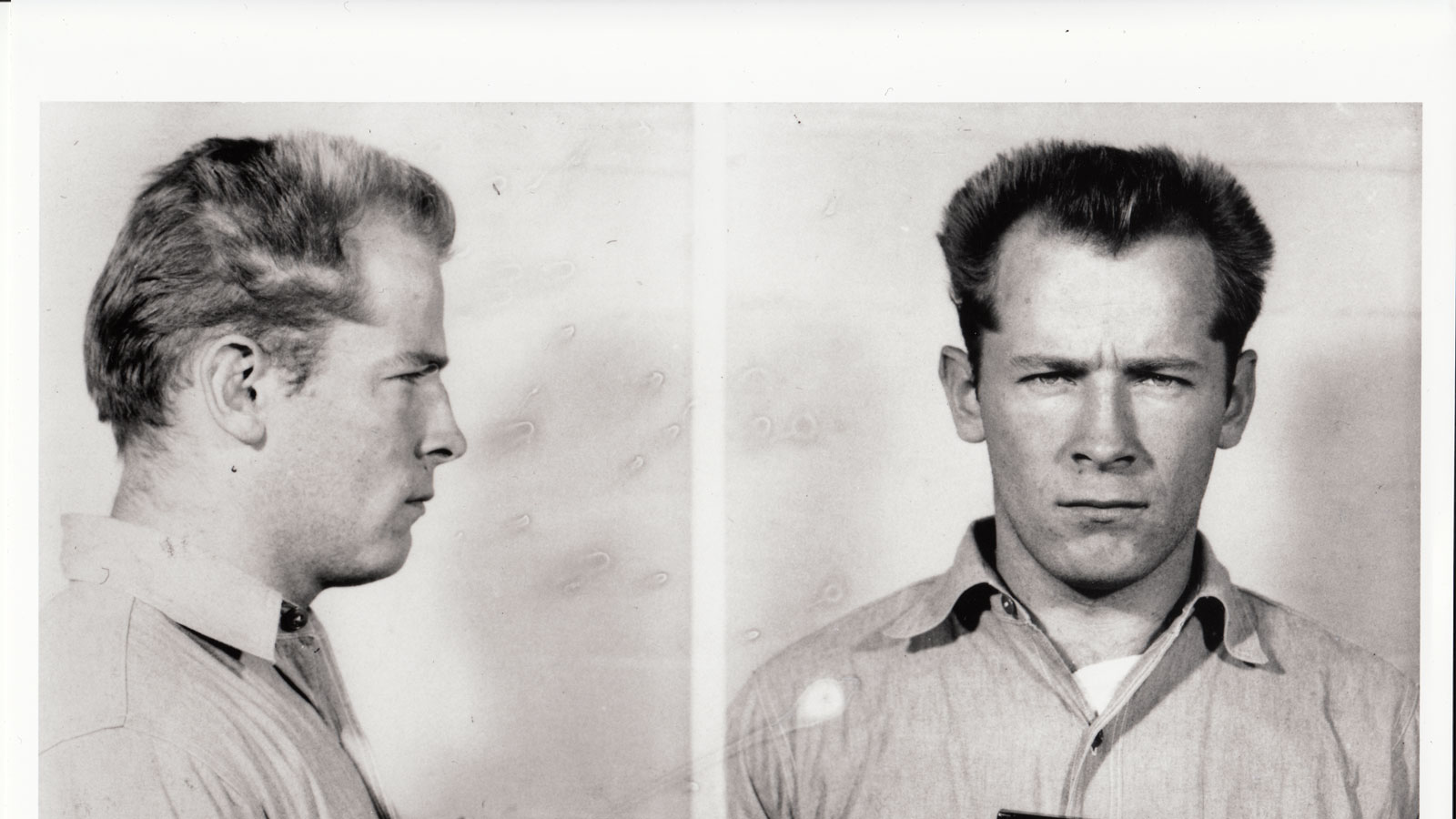

Notorious gangster James ‘Whitey’ Bulger tells his story

A controversial documentary presents an alternative theory of one of the most notorious gangsters of our times

Share

During his 16 years on the lam, James “Whitey” Bulger was supposedly spotted all over the globe. London. Uruguay. Sicily. Vancouver Island. Some tips were worth chasing, such as the time a California cop was certain he saw the aging Irish mobster at a movie theatre—watching, of all things, Jack Nicholson play a Bulger-inspired crime boss in Martin Scorsese’s The Departed. Other Whitey sightings were far more forgettable. In one infamous blunder, RCMP officers tackled and arrested a Toronto grandfather as he walked through a mall, convinced he was the notorious Boston gangster.

Even when he wasn’t trying, Bulger had a knack for tormenting the innocent.

In 2011, when FBI agents finally caught up with their second-most-wanted man (behind only Osama bin Laden), Bulger and his longtime girlfriend, Catherine Greig, were living in a bland, rent-controlled apartment in sunny Santa Monica, 4,800 km from his old Southie stomping grounds. He was 81 by then, with a snowy white beard that didn’t appear in any of his mug shots. Handcuffed, Bulger reportedly told the feds to look behind the drywall, where he had stashed the remnants of his criminal past: thick wads of cash and more than two dozen firearms.

Bulger, it turned out, was in the process of penning his own memoir—the “true account,” according to him. Sadly (or not, depending on the source), the book was far from finished, the first draft barely a hundred pages. There is, of course, no shortage of other Bulger hardcovers (17, at last count, including some authored by his once-loyal and equally homicidal underlings). Even before he vanished in 1995—tipped off by a crooked FBI agent that an indictment was imminent—his life story was the stuff of mob-syndicate myth: the tough, handsome bank robber who, after serving a stint in Alcatraz, went on to rule South Boston’s underworld with an effective mix of neighbourly charm and unspeakable violence. For more than two decades, Bulger not only paid off the federal crime-fighters who should have brought him to justice, but worked as a secret FBI informant to bring down his enemies.

Whitey was part boss, part rat—and all-powerful.

It’s a double-agent script straight out of Hollywood, which explains why two different production companies are rushing to tell the full saga (or at least some version of it). Boston natives Ben Affleck and Matt Damon are working on a Bulger biopic, with Damon slated to play Whitey and, next month, filming begins on a separate production starring Johnny Depp (based on the bestseller Black Mass by journalists Dick Lehr and Gerard O’Neill). If a gangster’s legacy is measured by which A-list celebrity plays him in the movie, Bulger remains firmly on top.

But how much of the prevailing Whitey narrative is actually true? Was he really an FBI informant? Or did the bureau concoct that story in a desperate attempt to cover up all the bribes and corruption that kept Bulger on the streets for so many years?

That one loaded question—rat or no rat?—is at the heart of a controversial new documentary that has beat the blockbusters to the gate: Joe Berlinger’s Whitey: United States of America v. James J. Bulger. Framed around the mobster’s dramatic racketeering trial (which ended last summer with 31 guilty verdicts, including 11 murder convictions), the film offers a unique, chilling window into Whitey’s sociopathic world, from the endless pain he inflicted on victims to the rampant graft that kept him in business. We even hear from Bulger himself, via a jailhouse telephone, professing love for his now-imprisoned girlfriend and explaining how he became “very human” during his time on the run.

But it’s Bulger’s insistence that he was never an FBI snitch—and the film’s willingness to examine his sensational claim at considerable depth, despite piles of evidence to the contrary—that isn’t sitting well with some veteran journalists, who have spent their careers exposing the truth. Kevin Cullen, a Boston Globe columnist and co-author of his own Bulger book, wrote that the documentary “quite intentionally, quite cynically, and quite inaccurately” gives legitimacy to an “outrageous” claim, while Lehr (whose book is the one being turned into the Johnny Depp flick) went so far as to accuse Berlinger’s portrayal of being “intellectually dishonest.”

The director is hardly surprised by the criticism. Truth be told, he expected it. “With all due respect, these are people who have made a cottage industry on having broken and reported the informant story,” says Berlinger, whose film will be screened at the Hot Docs Festival in Toronto from April 24 to May 4. “Look, I’m not saying whether he was an informant or not an informant, but I think it’s intellectually dishonest to just shut down the discussion. All I’m saying is: ‘Hey, if he was an informant, we still don’t have enough information as to how this was possible and who is responsible. And if he wasn’t an informant, man, there are some really deeply troubling questions.”

However far-fetched, Bulger’s informant denial is hardly new; at trial, it was the overriding theme of his defence. He fully admitted to being a callous crime boss who pocketed millions off illegal drugs and gambling, but he wanted the world to know he was definitely no rat (and that he would never kill a woman, even though he was charged with two counts of doing just that). For Bulger, his high-profile trial—“the Big Show,” as he dubbed it—offered one last opportunity to rewrite the record, facts be damned.

Most seasoned observers saw his courtroom strategy for what it was: a Whitey-wash. But, unlike the local press gallery, Berlinger explores the possibility that Bulger and his lawyers might be telling the truth. “We’ve heard his voice in the past on police tapes, but we’ve never heard his point of view expressed by him,” Berlinger tells Maclean’s. “I think that’s a big achievement of the film: We hear from Bulger. But I need to make very clear that this film is no apology for Bulger. Clearly—clearly—Bulger is a brutal, vicious killer who deserves to be behind bars, so I’m not an apologist for James ‘Whitey’ Bulger. But I think it’s fascinating to hear his perspective. It doesn’t mean we have to believe everything that comes out of his mouth. I’m treating the audience like a jury and allowing them to make up their own minds.”

Berlinger is most renowned for his Paradise Lost trilogy (co-directed by Bruce Sinofsky), which tells the story of the “West Memphis Three,” a group of Arkansas teenagers convicted of murdering three eight-year-old boys in 1993. In that case, the filmmakers were unabashedly convinced of the killers’ innocence, and the resulting movies are part documentary, part rallying cry. With Whitey, though, Berlinger is much more diligent about capturing every angle—ludicrous and otherwise—and allowing the viewer to reach a verdict. Yet, ironically enough, it’s that pursuit of “balance” that has some decrying the film as disingenuous.

“It’s important to let Whitey have his say, whether it’s himself or channelling it through his lawyers, insisting that he was never an informant,” Lehr says. “Fine, let him have his say. I think where the movie fails is to put that in the proper context: that this is Whitey saying this, and it goes against a mountain of evidence to the contrary that he was a rat.”

To be fair (and Lehr acknowledges this much), the film is about so much more than Whitey’s words. By Berlinger’s estimation, the informant question fills only 14 minutes of a movie that runs nearly two hours; the rest is a gripping tale of cops and robbers, lawyers and victims, all linked by one venal, remorseless man. More than anything, the documentary completely shatters Whitey’s pop-culture persona, which reached Houdini-like proportions during his years as a fugitive. Some still believe Whitey was a Robin Hood figure in Southie, a noble watchdog who helped the poor and kept drugs off the street. That couldn’t be more wrong.

And whether or not Whitey was a rat, there is another fact nobody disputes: The public still doesn’t know the full extent of Bulger’s twisted relationship with the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and why he literally enjoyed a licence to kill. “At the end of the day, what remains is that this is ultimately a story that has not been completely aired,” Berlinger says. “There are still swirling questions of corruption that have not been answered. The victims’ families deserve to know what really happened to their loved ones.”

At the very least, we know what will happen to Whitey Bulger. He will die behind bars, his legend slightly tarnished but still intact.