Rogers Writers’ Trust shortlist shows off accelerating diversity of CanLit

The Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize has historically recognized talent early. This year is no exception.

Share

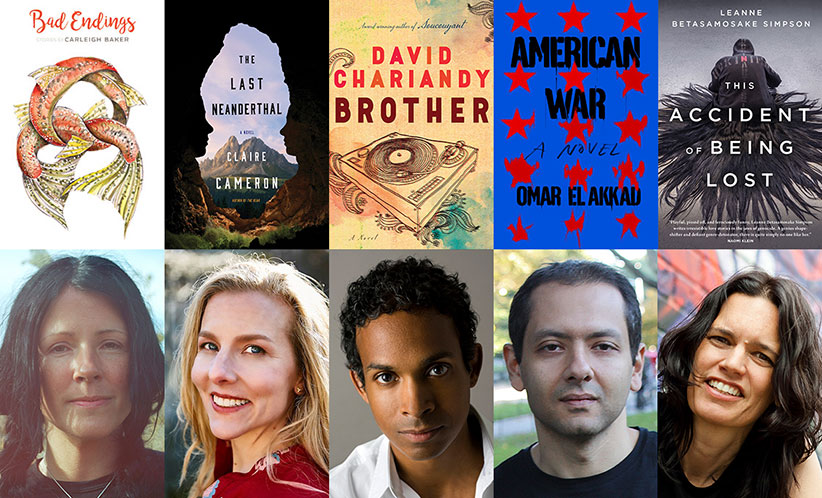

The accelerating diversity of CanLit has been apparent for years, both in the backgrounds of authors and in the genre-bending literature they produce. The trend is approaching a crescendo now, fuelled not just by gifted writers but by the nation’s own increased diversity in an era of deepening political tensions. Consider the shortlist, released today, for the Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize, arguably the most writerly and sensitive to change of Canada’s three major literary awards. The WT has the greatest degree of gender equality and — as the nation’s talent spotter — tends to recognize merit earlier. More WT winners have gone on to win the other awards than have travelled in the reverse, a record the Trust’s executive director Mary Osborne links to the WT’s writers advisory group, whose input makes for “juries who recognize talent very early.” The jurors who choose the 2017 finalists, the first eligible for the newly enriched winner’s purse of $50,000—double the previous $25,000—are all writers: Michael Christie, Christy Ann Conlin and Tracey Lindberg.

And whom did they select? David Chariandy, who grew up in the inner Toronto suburb of Scarborough as the son of Trinidadian immigrants, was picked for his novel Brother. It’s a beautiful piece of literature—a coming of age story, a meditation on family, a novel of place—but that place is the same much maligned suburb Chariandy grew up in, and the younger brother’s life in a racist milieu is central to novel’s power. Carleigh Baker’s book of short stories, Bad Endings, has a subtly wry title. The Metis author’s female characters, primarily engaged in trying to assert control over their lives—the politics are muted but real—may not come to happy ever after endings, or to any kind of real denouement at all, but her literary conclusions are powerful.

American War, by Omar El Akkad, born in Cairo and educated in Canada, is a straight-line, note-perfect extrapolation from the first U.S. civil war to El Akkad’s fictional second in 2074. And, of course, from the present day as well, in a story of how war continues past all reason, past all sight of the original cause, and may well come again. For the jurors, Leanne Betasamosake Simpson’s This Accident of Being Lost, is “genre-defying… like no other book you will ever read in your life.” Simpson is a member of Alderville First Nation, a scholar, writer and musician who first came to wider prominence during the Idle No More movement in 2012. She combines Nishnaabeg storytelling, poetry, music—there is a companion recording, f(l)ight—and serious activism in stories full of political anger and human kindness.

Both Claire Cameron and her novel, The Last Neanderthal, would seem to be the outliers in this list. Cameron is not a minority writer and her story is not set in the here and now, the way even El Akkad’s near-future dystopia is. Her story of two females—one human, one Neanderthal, both pregnant—mostly unfolds 40,000 years ago. But it has themes, ranging from the commodification of science to the demands of motherhood, that ring contemporary and the result, according to the jury, “is feminist literature of the highest order.”

READ: The new Neanderthals

Individual stories and diverse authors, then, but the nominees are linked by more than literary quality. David Chariandy is not sure how to answer when asked what he thinks has made Brother the most buzzed-about book of the year. “I work on my books for years, 10 years on this one, never knowing how they’ll resonate with others. I never assumed it would get this response.” But he also acknowledges we are in politically loaded times, when readers are open not only to diverse voices speaking of familiar themes—love, home, family—but of harsher, more marginalized, lives. “Since I became an adult,” says Chariandy, an English professor at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, “I’ve been reading black Canadian authors, black Americans, Caribbean writers. The issues I’ve confronted I’ve seen addressed for decades—this conversation is deep, the legacy is powerful. I have to get used to those, who were not connected to this conversation, now saying my book is ‘timely.’ Maybe, perhaps, it’s been pushed into the mainstream, maybe voices that once could be ignored can’t be any more. But this is certainly not about me.” True enough: it’s about us.