Why rap regionalism is fading

East Coast? West Coast? It’s never mattered less in rap where you’re from.

Share

A month ago, rapper Nicki Minaj leaked the song Chiraq from her upcoming album. That’s a local nickname for Chicago—a reference to the Iraq-level violence and gunplay that mars swaths of its inner city and inspired the “drill” subgenre of rap, all nihilism and hostility and pitter-patter militarism. Minaj, of course, is the Barbie-affecting queen from Queens, New York City, with no claim to understanding the realities of those streets. But she nevertheless adopted the sound and title for the song, and it gathered all the right buzz from most hip-hop circles, and little of the backlash one might expect.

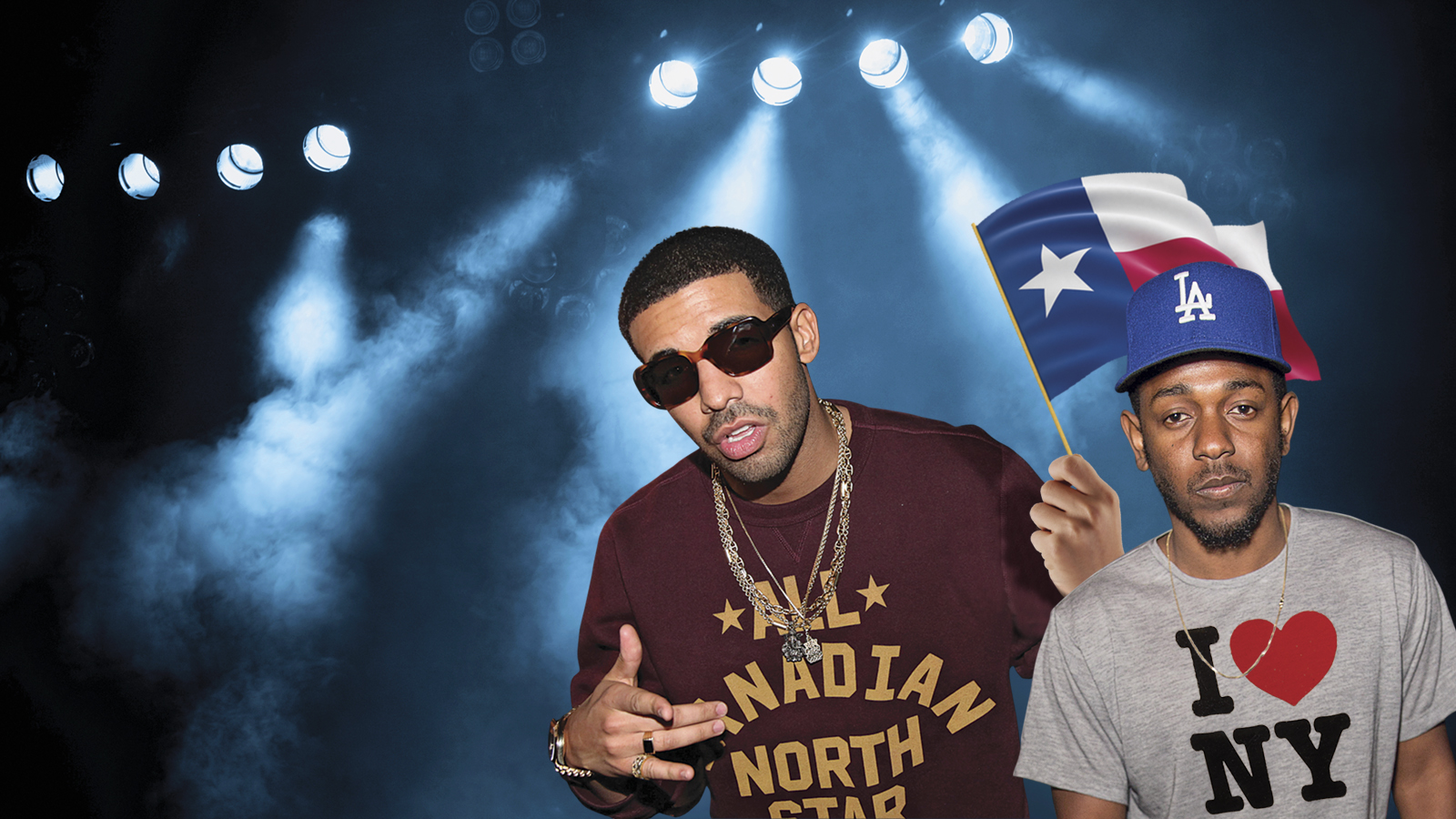

She’s not alone in borrowing the identity of a different place. Despite his Harlem roots, A$AP Rocky’s sound hews closer to the slower, druggier rap style of the South. Drake, Toronto’s champion, shouts out Houston about as often as he does the north; in one particularly polyglot expression, he borrowed a few rhymes from an obscure Bay Area rapper to claim he’s “big in the West / like I’m big in the South.” Last year, Kendrick Lamar delivered a searing verse on the Big Sean song Control in which the L.A. rapper crowned himself the king of New York (and rattled off a list of star rappers he sought to musically murder)—the equivalent of a Buddhist making a claim to Mecca. It was a bold incursion that raised some hackles, but none of the kind of mid-1990s feuding that culminated in the deaths of Tupac Shakur and the Notorious B.I.G. and has haunted the genre ever since. “Rap’s become this thing where now somebody can shout out New York and not be from there and it doesn’t become a scandal,” said Mickey Hess, a professor at Rider University.

It all suggests that rap regionalism, a defining tenet from the music’s earliest days, is fading. In the past, it was important to pay respect to your neighbourhood and its unique sound no matter where your career took you. That meant shouting out your city, referencing local icons, producing its particular style of music and defending it against rap intruders. But place in rap now seems more about aesthetic choices than cultural obligation. “It’s a switch they can turn on and off,” said Murray Forman, associate professor of communications at Northeastern University and author of The ’Hood Comes First: Race, Space, and Place in Rap and Hip-Hop. “The Internet has facilitated a sense of placelessness.”

Indeed, while rap once spread through the migration of physical tapes from hip-hop’s cradle in New York to budding scenes in L.A., Philadelphia or Detroit, the web means rap can be more experimental than ever. Someone growing up in New York can be influenced just easily by Miami trunk-rattling as by Bronx boom-bap—it’s the same distance on the Internet. “Producers and rappers don’t even have to be in the same room anymore. Newer artists have grown up where their exchange is online,” said Hess. “It’s less, ‘How established are you where you’re from?’ It tends to start online—Twitter followers, YouTube views.”

So regional rivalry is dead, but regionalism, strictly speaking, isn’t. It may be on the national front, but the interests of the masses have always been fickle and single-minded; right now, with Atlanta trap beats infusing even pop chanteuse Katy Perry’s latest single, it’s the South’s turn in the sun. More interplay between regions, says Dave Cook, a journalist, radio DJ and adjunct professor at San Francisco State College, means rappers can diversify and gain credibility in other regions. This new kind of sample-happy regionalism can only exist if the original scenes are catalyzed themselves, he adds. “The scene, 20 years ago, might’ve been what you lived and died by, but today, the scene is a jump-off,” said Cook. “A good artist knows that you want to be part of many scenes.” As one kind of place recedes, too, there are new kinds opening up, argues Forman, pointing to the music video for Jay Z’s Picasso Baby, filmed in the Museum of Modern Art and loaded with references to artists like Warhol and Koons.

For his part, Lamar’s bold claim was less incendiary and more a reflection of this new post-regional world. “It’s not about the coasts, it’s not about what side we’re on. It’s about being as great as Biggie, as ’Pac,” he said in an interview with Power 106. “People trying to make it a rivalry—that’s old school, homie. We’re black men out here trying to uplift the culture.”