Is Under Armour ready for the big leagues?

The company is challenging Nike on its own turf

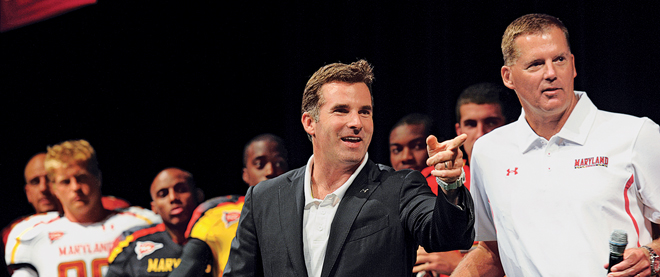

The Washington Post/Getty Images

Share

Kevin Plank, the founder and CEO of sportswear apparel company Under Armour, has been a long-time supporter of the University of Maryland’s football team, the Terrapins, where he was once a special teams captain. But the relationship entered a new phase last week when the Terps’ new, Under Armour-made uniforms were unveiled for the upcoming season—all 32 variations of them.

The over-the-top, mix-and-match approach—there are four different colours of Terps jerseys, four different colours of pants, and two different colours of helmets—is all about marketing buzz and drew immediate comparisons to Nike’s efforts to use football players at the University of Oregon (Nike founder and chair Phil Knight is an alumni) as human billboards. “The sheer number of articles that have appeared last week about the Under Armour jerseys shows that it’s already been a successful marketing campaign,” says Matt Powell, an analyst at SportsONESource, which tracks sportswear sales in the United States.

It’s not the first time that Plank has challenged industry giant Nike on its own turf. On the eve of Under Armour’s entry into the Nike-dominated $2.5-billion U.S. basketball shoe market last year, Plank boasted that it was only a matter of time before he owned the category. “I’m 38,” he told Bloomberg news. “I’ve got a long time [to get there].” As for Nike, he said, “those guys are old.”

Under Armour still has a way to go before its interlocking logo rivals the storied Nike swoosh on the court and elsewhere, but the Baltimore-based company continues to pick up some serious speed. Last year, the company generated more than $1 billion in revenue, about double that of five years ago. (Nike spends more than twice that on its annual marketing budget). Under Armour’s shares, meanwhile, have soared more than 70 per cent to US$60 over the same period.

Plank predicts sales will double again within three years, fuelled by gains in the huge footwear market. But analysts warn that, despite a big attitude and an endorsement deal with NFL quarterback Tom Brady, Under Armour is still a small fry when it comes to footwear. It currently has about 1.2 per cent of the market compared to Nike’s 36.8 per cent—and that doesn’t include other Nike-owned brands like Jordan (9.3 per cent) and Converse (2.4 per cent). Still, the fact Under Armour is even being mentioned in the same breath as titans Nike and Adidas demonstrates just how far Plank has come in the 15 years since he began making form-fitting workout shirts in his grandmother’s basement.

But as with any fast-growing company, there are questions about Under Armour’s ability to live up to expectations. Most people who buy Under Armour gear wear it on the field and in the gym, whereas Nike and Adidas clothing is just as likely to be donned for a trip to the mall, or backyard barbecue.

Camilo Lyon, an analyst with Canaccord Genuity, is bullish that Under Armour is destined for a similar mass appeal. He said last week that Under Armour’s “expanding brand acceptance” has paved the way for growth in new segments, citing in particular the company’s moisture-wicking Charged Cotton garments. “We view Charged Cotton as a product line that can dramatically further the brand’s awareness off the field as it enables the Under Armour consumer to wear the brand throughout the day in a variety of settings,” Lyon wrote in a report that placed a “buy” rating on Under Armour’s stock and a 12-month target of US$75. Lyon noted that the size of the total “active use” sportswear market in the U.S. is $11.3 billion, compared to the $3 billion synthetic active use market in which Under Armour now competes. The broadly defined “active wear” market—basically anything sports-inspired—is worth about $57.6 billion.

Expanding Under Armour’s customer base will require careful brand building. And, ironically, that means continuing to narrowly portray Under Armour products as gear for growling linebackers and sweat-drenched basketball players. “They are focused on authenticity,” Powell says. Under Armour has also learned from past marketing mistakes. Like when it paid millions for a 2008 Super Bowl ad—described by Plank as a “coming out party”—for a yet-to-be-released cross-training shoe, only to have investors blitz its stock and consumers express confusion when they couldn’t get their hands on the sneakers following the big game. Powell says Under Armour is wisely taking a more low-key approach with its basketball shoes by getting them on the feet of young high school and college players, as well as up-and-coming NBA stars like Brandon Jennings, a point guard for the Milwaukee Bucks.

But Plank’s signature braggadocio remains intact. A recent basketball ad takes thinly veiled swipes at Nike-backed NBA superstars LeBron James and Kobe Bryant. Plank is “prone to make bold statements,” says Powell. “But they’ve accomplished a lot in a relatively short period of time.”