Are we seeing a craft brewery bubble, or just a frothy boom?

The number of craft breweries in Canada has exploded over the past few years, driven in part by government subsidies. Is this a beer bubble about to burst?

Photograph by Cole Garside

Share

At the heart of many of the new craft breweries launching in Canada these days is a familiar entrepreneurial narrative—guys or gals (but mostly guys) in office jobs tire of their drone lifestyles and choose to pursue their love of good beer by going into business for themselves as brewmasters. It’s baked into the business plan at Ottawa’s Broadhead Brewing Company (“Brew beer, sell some, drink some, grow large beards, quit our day jobs”). In Calgary, the founders of Tool Shed Brewing Company tell of quitting their day jobs at an IT company. Likewise, the two founders of Toronto’s Halo Brewery, which launched earlier this year with the tagline “from basement to brewhouse,” both quit their day jobs to start the business. In fact, quitting your job to start a brewery has become such a cliché that it’s even been immortalized in a bank commercial.

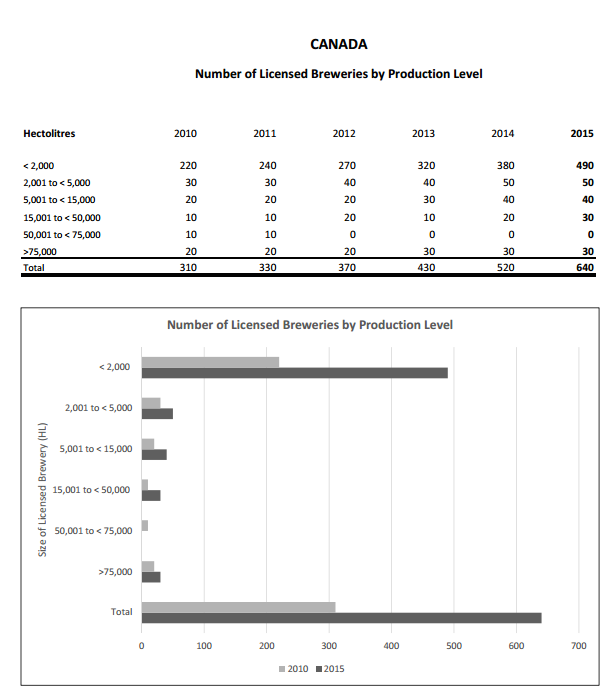

So there’s no question a boom is under way. Back in 2010, there were 310 licensed breweries across Canada, according to Beer Canada, but by 2015 that number had more than doubled to 640. (Tap or hover over the chart to see detailed figures.)

Politicians are keen to get in on the action, too. In Ontario, where the number of breweries has nearly tripled in six years, the provincial government this year invested $1.6 million for 20 craft breweries for everything from capital to marketing. The announcement in mid-June coincided with “craft beer week.” Around the same time, B.C. announced $10 million in support to breweries there through a 25 per cent reduction in the provincial liquor distribution board’s mark-up for local beers, while a new grant program in Alberta aims to inject $20 million into the craft beer sector, in the name of diversifying the economy. And that’s just in the past year—government support for craft breweries has been steadily rising over the last decade.

Yet despite the meteoric growth in the number of breweries across the country, each competing for space on chalkboard menus at bars and fridge space at the beer store, the actual volume of Canadian-made beer being consumed in the country fell by 3.4 per cent from 2010 to 2015—the equivalent of around 10 million two-fours.

“There’s only so much beer the market can absorb,” says Jordan St. John, a beer historian and co-author of the Ontario Craft Beer Guide. “I think we’re reaching a tipping point.”

Is the microbrewery bubble about to burst? There’s certainly anecdotal evidence that some breweries that have entered the frothy market have struggled to make a successful business out of it.

In Hamilton, the Ontario Breweries award-winning craft brewery Garden Brewers, which launched in 2014, announced in a July blog post that is couldn’t afford to go on. The Hog’s Head Brewing Company in St. Albert, Alta., reportedly shut down in the summer of 2015 after just three years of operation. And in Squamish, B.C., the One Duck Brewing Company, which garnered more than $16,000 from a Kickstarter campaign in the summer of 2015, announced in an October Facebook post they were going to have to close up shop and file for bankruptcy, not even having made it to the grand opening.

But the rest of the breweries must be finding a home for their suds to stay afloat. At least that’s the assumption of Pedro Antunes, deputy chief economist at the Conference Board. “If they’re not selling, they’ll be out of business pretty quickly,” he says. “[Beer] isn’t like oil. You can’t just store it away in barrels and hope for a better day.”

So if beer lovers are thinking of joining the microbrewery world, without running fellow small-time brewers out of business, it’ll have to come at a cost of the major players. “There may be one big brewery closing and that allows for several small breweries to take that space,” Antunes says.

But the big brewers aren’t closing up shop just yet. The number of licensed brewers who produce more than 7.5 million litres a year has increased from 20 to 30 since 2010, according to Beer Canada’s 2015 industry trends report. There’s also growth in the number of brewers who produce anywhere from 2,000 to 50,000 hectolitres. Meanwhile, the biggest increase is for the smallest of microbreweries—those producing less than 2,000 hectolitres a year (or less than 25,000 cases of 24)—which jumped from 220 to 490 since 2010.

The other possible way for everyone to stay afloat is for beer drinkers to simply pay more—and indeed sales have risen nationally even as the volume of beer sold has declined.

The question becomes, is there enough room to keep hiking prices for even more new breweries to enter the market, let alone to keep the lights on at all those struggling to get established?

At this point, St. John predicts the number of breweries in Canada is reaching a cap as opposed to a bubble, in which when one microbrewery goes under, another one will emerge to take its place. “They’re never going to expand a huge amount but they’ll make somebody’s living,” he says. “And it’s pretty good living if you don’t mind aiming small.”