Housing bubble, take 2

As homes in hard-hit cities languish in foreclosure, U.S. housing prices are reaching dangerous new heights

Joe Raedle / Getty Images

Share

America’s housing collapse was supposed to be the kind of catastrophe that comes around once in a generation. Instead, some analysts are warning that a new bubble is forming just five years after the last one burst. This time, it’s not subprime lenders helping to push up prices, but easy-money government policies and billion-dollar hedge funds.

Home prices are up more than 12 per cent across the U.S. this year, according to the S&P/Case-Shiller Home Price Index. And they are soaring in some past bubble cities: up nearly 40 per cent in Las Vegas, 30 per cent in Phoenix and 20 per cent in San Francisco. Bidding wars are erupting in cities that were among the hardest-hit during the crash, where thousands of homes languish in foreclosure, even as buyers complain about a shortage of new listings.

“I’m beginning to see signs, not just in my district, but across the country, that we are entering, once again, a housing bubble,” Richard Fisher, chair of the Dallas Federal Reserve said after a speech to the Economic Club of New York last week. He pointed to the $40 billion worth of mortgage-backed securities that the U.S. Fed is buying each month, a policy designed to sop up many of the toxic subprime lending still weighing down the balance sheets of the nation’s banks, but that Fisher warned is helping to fuel low mortgage rates.

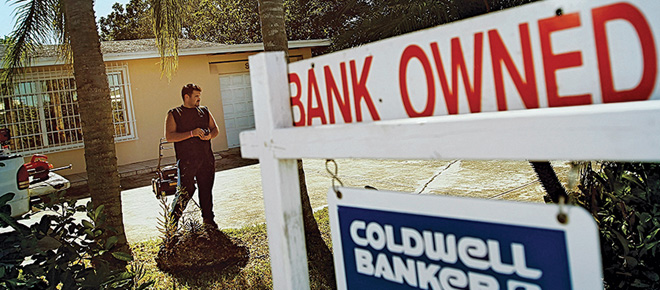

Meanwhile, 80 per cent of the nearly 525,000 homes in foreclosure in the U.S. still haven’t been listed for sale, sometimes years after they were repossessed by the bank, according to a new report from foreclosure-listing firm RealtyTrac. Laws in many states weren’t designed to handle the sheer volume of foreclosures, says RealtyTrac vice-president Daren Blomquist. At the same time, several major Wall Street banks were forced to suspend proceedings after employees were found to be foreclosing on millions of homeowners with improper—sometimes fraudulent—paperwork. That’s led to a massive backlog in foreclosures, which has helped push up house prices even further by restricting the supply of new listings. Nearly a third of bank-owned homes are sitting vacant, while nearly half are still occupied by previous owners, who are now living there mortgage-free. “These properties are going to be listed for sale at some point, but they’re being held off the market, in many cases, for a lengthy period of time,” says Blomquist. “That could, in the short term, be artificially inflating house prices.”

Even when homes do make it onto the market, they are being snapped up by hedge funds and private equity firms. Institutional investors have purchased as many as half the homes for sale in some cities in the past year, says Florida real estate analyst Jack McCabe, sometimes paying as much as 25 per cent over market value. Rather than try to flip them for profit, firms have been renting them out, often to previous owners who can no longer afford them. Blackstone Group has spent over $4.5 billion to amass more than 30,000 rental homes in the past year, and has plans to invest an additional $5 billion more in American real estate. Toronto-based Delavaco Properties Inc. has bought up more than 600 homes in South Florida and expects to buy close to 900 more, with most rented out to families who qualify for government-subsidized rent. “The funds are driving prices higher and artificially escalating values,” McCabe wrote in an analysis last month. He predicted the bubble would last another two years until mortgage rates start rising, prompting investors to dump properties. That could spark yet another crash, which would be a devastating blow to an economy that’s still reeling from the last one.