Why the world’s best and brightest struggle to find jobs in Canada

Why do skilled immigrants often fare worse here than in the U.S. and U.K.?

Aaron Harris/CP

Share

For a time, Sanjay Mavinkurve and wife Samvita Padukone were held up as poster children for Canada’s open and flexible immigration system, long touted for the benefits it brings to both the country and its newcomers. When the couple married in 2008, Mavinkurve—born in India, raised in Saudi Arabia and trained at Harvard University—was living in Silicon Valley, where he led a team of engineers designing Google maps for mobile phones. Padukone was working in finance at Singapore’s largest investment bank. Mavinkurve’s temporary U.S. work visa didn’t allow his wife to work in the States. So Google arranged to transfer Mavinkurve to the company’s office in Toronto, where Padukone, with degrees in engineering and finance and experience in international banking, hoped to land a job.

Their story inspired a flurry of alarmist news coverage south of the border on how America’s overly bureaucratic immigration system was putting the country’s economic future at risk. Profiles in the Canadian media, meanwhile, pictured the young couple in the typical new immigrant pose: sitting on the couch of their threadbare downtown Toronto apartment, smiling beneath a Canadian flag.

In the end, their story turned out to be less a picture of the Canadian dream than an image of the ugly reality facing so many Canadian immigrants. Padukone struggled to find a job. Calls to employers went unreturned or recruiters told her she would need Canadian work experience to qualify. With extended family already living in Canada, the couple expected a slow start, but was shocked by how difficult life here turned out to be. “I was trying to deny these thoughts in my head that my wife wasn’t facing these issues,” says Mavinkurve. “But then I’d see the taxi drivers with the Ph.D.s and the ads on TV saying, ‘hire a skilled immigrant.’ ”

In late 2009, the couple packed up and moved to Seattle, where Padukone, finally armed with a U.S. work permit, landed the first job she applied for: at Amazon’s head office. Their short time living in Canada taught the couple a lot about what it’s like to immigrate to Canada and, says Mavinkurve, it’s “not what any Canadian wants to hear.” “Canada is, by and large, not friendly to immigrants,” he says.

Canada’s “points system,” the first such system in the world, was designed to build a multicultural society based on selecting those with the kinds of broad, transferable skills that would ensure them long-term economic success. But in recent decades it has had the opposite effect. Even as Canada has worked diligently to attract the world’s most educated workers, the country has witnessed a dramatic decline in the economic welfare of its most skilled immigrants. It’s a decline other countries—nations far less welcoming to highly skilled imimigrants than Canada—have managed to avoid.

In 1970, men who immigrated to Canada earned about 85 per cent of the wages of Canadian-born workers, rising to 92 per cent after a decade in the country. By the late 1990s, they earned just 60 per cent, rising to 78 per cent after 15 years, according to Statistics Canada studies. These days, university-educated newcomers earn an average of 67 per cent of their Canadian-born, university-educated counterparts.

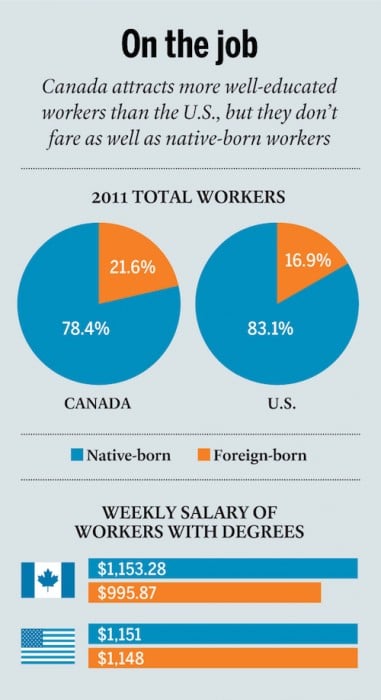

That deterioration is even more severe since recent immigrants are far more educated and experienced than in previous generations. Between 2000 and 2007, nearly 80 per cent of skilled workers who immigrated to Canada had a university degree, compared to about 25 per cent for the Canadian-born population, reports Statistics Canada. By far the largest gap in wages between immigrants and Canadian-born workers was among those with university degrees. Nearly half of chronically poor immigrants living in Canada are those who have come as skilled workers.

The implications for the country are huge, given that Canada has one of the highest rates of immigration in the world and attracts far more skilled immigrants than most other Western countries. Economic migrants—those chosen because they’re thought to have the kinds of skills that can boost a country’s economy—represent roughly half of all Canadian immigrants, compared to around 16 per cent in the U.S. The declining economic welfare of immigrants is “a huge problem,” says Immigration Minister Jason Kenney. “It’s impossible to calculate the opportunity cost of productivity, the cost to our economy, represented by the unemployment and underemployment of immigrants.”

In contrast to the Canadian experience, immigrants to the U.S. have virtually closed the income gap with American-born workers. In 1980, U.S. immigrants earned about 80 per cent of American-born workers, a gap that was roughly the same in Canada. By 2011, U.S. immigrants earned 93 per cent of native-born workers, while foreign-born college graduates now out-earn their American counterparts.

During the last recession the unemployment rate for foreign-born university grads in Canada topped out at 8.4 per cent in 2010. (Among those who had lived in the country less than five years, it was more than 14 per cent.) By comparison, unemployment among foreign-born university graduates in the U.S. was 4.4 per cent. Even during the worst of the recession, the unemployment rate for Canadian-born university graduates hit a mere 3.5 per cent.

And it’s not just the U.S. that’s putting Canada to shame. In the U.K., skilled immigrants from every country except Bangladesh now out-earn locals and employment rates are roughly the same among British-born workers and immigrants. Australia overhauled its immigration system in the 1990s, giving preference to immigrants who would be most likely to land a job, and saw immigrant employment and earnings steadily improve. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), nearly 23 per cent of Canadian immigrants live in poverty compared to an OECD average of 17 per cent. Canada is also one of the worst at matching immigrants’ education to their jobs, ahead of only Estonia, Italy, Spain and Greece. Just 60 per cent of highly skilled Canadian immigrants were working in jobs that required highly skilled workers, compared to an OECD average of 71 per cent.

This immigration dilemma affects wages more broadly, too. Comparing economic impacts of immigration in Canada and the U.S., Harvard economist George Borjas and former Statistics Canada senior researcher Abdurrahman Aydemir found that Canada had admitted more university-educated workers than the economy actually needed, which drove down the wages of jobs requiring a university degree and drove up the wages for the kind of low-skilled jobs that didn’t even require a high school education. In the decade following the early 1990s, when Canada abandoned its long-standing practice of tying immigration numbers to economic growth and switched from admitting mainly relatives of Canadian residents to admitting mostly skilled immigrants with no local ties to the country, wages for university graduates fell eight per cent, while wages for high school dropouts rose eight per cent. That shift has primarily affected immigrants, since a far higher proportion have a university degree compared to Canadian-born workers. Immigration in the U.S. had the opposite effect. A huge influx of low-skilled illegal immigration from Mexico and Central America caused wages for American high school dropouts to fall 20 per cent, while a move toward employer-sponsored visas for skilled workers boosted wages for workers with postgraduate degrees by the same percentage.

The sheer number of immigrants with such a vast array of foreign work experience and university degrees has meant that Canadian companies now routinely demand “Canadian work experience” simply as a way to screen out thousands of potential job applicants. The practice smacks of discrimination. University of Toronto economist Philip Oreopoulos sent thousands of resumés to posted job ads and found that changing the name on a resumé from anglophone to Indian or Chinese reduced responses from employers by 50 per cent, with most employers saying they assume a foreign name meant the worker had poor English. But the demand for “Canadian experience” is also a result of recruiters simply being inundated with so many resumés that spending a few minutes going online to research foreign universities and work experience wasn’t worth the hassle. “Their initial reaction to someone coming from another country may be, ‘I don’t know about this guy, I don’t want to take the chance,’ ” says Oreopoulos. “But it’s an easy gut reaction to have when you have 200 resumés to go through.”

American employers are likely just as discriminatory as Canadian companies, but because workers need a job offer to immigrate, that discrimination tends to happen before prospective immigrants have been given a work permit and have made plans to move to a new country.

Critics have attacked America’s system of temporary employment-based immigration, since it leaves immigrants vulnerable to the whims of their employers or the economy. But Mavinkurve says the process has some unexpected benefits. “The American system has a perverse way of selecting for risk-takers,” he says. “Whether it’s true or not, the perception is the freebies are much fewer in America than Canada and that has a way of self-selecting for people who say, ‘I don’t necessarily care about guaranteed free health care. I don’t care if I get kicked out of America. I want to go to the country that gave me Facebook and Google.’ ” It’s common in India to hear of immigrants returning home from the U.S. because they lost their job and had their temporary work visa revoked, he says. Those same stories don’t filter back among skilled immigrants who move to Canada as permanent residents, giving the impression that Canada is a better place to come look for steady work.

Kara Somerville and Scott Walsworth, a husband and wife team at the University of Saskatchewan, travelled to India in 2011 to investigate why, after decades of detailed stories about newcomers living in poverty in Canada, new immigrants were consistently shocked by how difficult it was to break into the job market. Interviewing 500 Indian university students, they found Canadian immigrants go to great lengths to disguise just how much they are struggling in their new country, mostly because they face intense social pressure to portray themselves as successful back home. Instead of describing their overcrowded apartment building, they take pictures of themselves in leafy upscale neighbourhoods. They boast about the company they work for without mentioning they work in the cafeteria. They might talk about struggling, but only for the first few months. “Not for five years,” says Somerville. “Not redoing their entire master’s or Ph.D.s.”

For immigrants like Mavinkurve, the solution is pretty simple: let employers decide which of the world’s skilled workers it needs and leave governments the job of ensuring companies and immigrants don’t abuse the privilege. “The biggest flaw in the Canadian system is that you have a system where bureaucrats in Ottawa decide who has the right skill set to contribute to the Canadian economy,” he says.

That’s ultimately where Canada’s immigration system is heading, says Jason Kenney, in an interview. Since taking office, the Conservatives have steadily tinkered with the system, boosting the number of temporary work visas and shifting more control to provincial governments. The most dramatic changes come next year, when Kenney says the government will scrap the decades-old points system in favour of something he calls an “expression of interest,” based on the skilled-worker systems in Australia and New Zealand. Instead of receiving points based on a mix of language skills, education and work experience, prospective immigrants will need to have their language skills and credentials assessed by an independent third-party service. If they pass, they’ll be put into a pool of people approved for immigration. Employers can browse lists of workers, and if they find an employee they want to hire they can apply to bring them over within a year, rather than the typical five-year wait list for the skilled-worker program. “It’s like a dating service to connect employers with prospective immigrants,” says Kenney.

It would be a substantial shift and also an admission by the federal government that the points system, the cornerstone of Canada’s immigration system for the past 50 years, hasn’t worked. “I wouldn’t say it’s been a failure,” Kenney says, “but the outcomes have been underwhelming.”

An employer-driven immigration system is bound to be controversial. Already, Canada’s temporary foreign-worker program has been under fire after a Chinese mining company was allowed to employ more than 200 Chinese in a B.C. coal mine. Last week, Royal Bank was forced to apologize for shifting some Canadian jobs to workers in India, while the outsourcing company it hired used temporary foreign workers.

Critics contend that placing the short-term needs of employers at the heart of the skilled immigration system isn’t a cure-all, since the skills employers need today might not be the ones they’ll need in five or 10 years. But others warn the current system is far worse. “It’s an important discussion because we have a policy specifically designed to pick the immigrants that are most likely to succeed in the labour market,” says Oreopoulos, “and yet we’re completely failing them.”

More importantly, says Somerville, ensuring future generations of immigrants don’t end up underemployed and living in poverty will require a complete overhaul of what it means to immigrate to Canada. “It really means changing the mentality that Canada is entirely a land of opportunity,” she says. For Canadians and immigrants alike, that message will be hard to face.