Running of the bulls

Why some experts believe this is the start of a once-in-a-generation boom

Scott Olson/GETTY IMAGES

Share

Ralph Acampora has nearly 50 years of experience as a stock market technician—someone who attempts to predict future stock movements by studying their historical patterns. But he says he learned one of his most important lessons not by poring over data on a powerful computer, but while eating dinner 43 years ago at Delmonico’s, a Lower Manhattan institution that traces its roots to 1827. He was seated next to a 70-year-old named Kenneth Ward, then one of the oldest market technicians on Wall Street.

Acampora, a founding member of the Market Technicians Association, asked Ward which 20th-century market had been most difficult to grasp, saying he figured it must have been the crash of 1929. But Ward replied in a gravelly voice, “Naw kid, that was a lay-up. Don’t get me wrong. We lost a lot of money, but the most difficult market I ever worked was in the 1960s.” Acampora was perplexed. Other than the “flash crash” of 1962, the Dow Jones Industrial Average—an index that tracks 30 U.S. blue chip companies—spent the rest of the decade marching to new heights. “I said, ‘But Mr. Ward, the market was going up.’ And he said, ‘It sure did, young man, but it rolled over everybody. And that’s because nobody believed it.’ ”

More than 50 years later, investors are wrestling with the same problem. Many pulled out of equities in 2008 and stuffed what was left of their money into bonds and other “safe” investments—what seemed like a sensible measure at a time when Wall Street was imploding and talk of a second Great Depression loomed large. Then a surprising thing happened. After hitting a low in March 2009, the stock market went on one of the greatest bull runs ever, surging nearly 100 per cent in just four years. The Dow recently crossed the 14,000-mark, a level not reached since 2007. The broader S&P 500 Index, now around 1,511, is also closing in on its record high of 1,565 points. Even Germany’s DAX, an index with a front-row seat to the European debt crisis, is approaching its July 2007 record of 8,106 points. (In Canada, meanwhile, the S&P Composite Index is still a few thousand points shy of its 2008 all-time high of just over 15,000, largely because it’s heavily weighted toward resource companies at a time when the worldwide outlook for commodities has been slipping.)

Those who invested in U.S. stocks and resisted the urge to sell four years ago have made their money back, while steely-nerved opportunists, who bought shares as everyone was rushing for the exits, enjoyed tech-boom-sized returns. Not surprisingly, those who fled stocks (and are frustrated with the anemic returns offered by fixed-income investments in an era of rock-bottom interest rates) are beginning to rethink their strategies. As much as $11.3 billion moved into U.S.-based equity funds during the first two weeks of 2013, the biggest two-week net gain since 2000, according to mutual- and hedge-fund tracking firm Lipper. The question now for investors is: does it really make sense to dive back into stocks on the heels of a four-year bull run—particularly when the U.S. economy is far from healed, Europe remains mired in a recession and China’s growth is slowing?

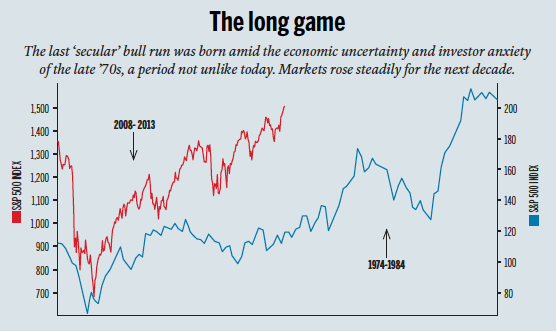

A growing number of experts say yes—and not just because they believe there’s life left in the current rally. It’s still early days, but many are convinced that what we’re witnessing is a once-in-a-generation move to a “secular” bull market—one that could last for a decade or more and is driven by fundamental growth, not mere speculation. That’s in contrast to the last 10 years, which saw markets end up in roughly the same place where they began.

Jeffrey Saut, the chief investment strategist at Raymond James, has suggested the early signs of a new, long-term bull market might include a move toward U.S. energy independence, the return of outsourced factory jobs, a recovering U.S. housing market, strong auto sales, a tech boom and, critically, investors who appear to be returning to stocks in bigger numbers. Acampora, too, feels he’s seen this movie before. “This is very much like August of 1982 when we made that bottom and had the beginning of an 18-year-long run,” he says. “I can’t spell the word ‘economics’ or balance my own chequebook. But I’m a damn good student of the market. And this market is telling me, ‘Hey baby, I’m going up.’ ”

The greatest bull markets climb a wall of worry, goes an old investing adage. And there’s been no shortage of things for people to worry about of late. The past four years have been chock full of ominous developments: stubborn U.S. unemployment, round after round of emergency monetary measures, the European debt crisis, the U.S. fiscal-cliff standoff, China’s slowing economy. The list goes on.

It was a similar story back in the early days of the ’80s Reagan-era bull market, which was sparked by the hope that the economy-killing era of double-digit interest rates and inflation was finally drawing to a close. Financial Post columnist Patrick Bloomfield wrote that it was hard to believe “we’ve suddenly wandered into some kind of Nirvana where corporate earnings will bloom and everything in the economic garden will smell lovely.” That was on Sept. 4, 1982, a day after the Dow closed at 925 points. Five years later, it would hit 2,709. By the end of the 1990s, it would reach nearly 11,000.

Experts say the apparent disconnection between stock market performance and the broader economy is due to a popular misunderstanding of the relationship between the two. Although they are related, the stock market is a leading indicator of economic activity—a measure of what investors believe will happen six months to a year from now. The economic outlook, in other words, is already baked in. “You don’t get rewarded for investing in something if you’ve already seen all the cards,” says Chris Johnson, the director of research at Ohio-based JK Investment Group.

In fact, Acampora argues this is what the early days of a secular bull market should look like: investor nervousness in the face of unmistakably solid performances from U.S. corporate stalwarts such as General Electric Co. (up more than 200 per cent since 2009 to $22), Bank of America Corp. (up more than 250 per cent to $11.50), Boeing Co. (up more than 145 per cent to $75) and Exxon Mobil Corp. (up more than 35 per cent to $90). Moreover, many of those same corporations cut costs to the bone during the recession and are now more profitable than ever. “They’re sitting on tons of cash,” Acampora says. And that suggests a flurry of market-driving activity—mergers, leveraged buyouts and IPOs—once executives are convinced the economy is solidly back on its feet.

In fact, Acampora argues this is what the early days of a secular bull market should look like: investor nervousness in the face of unmistakably solid performances from U.S. corporate stalwarts such as General Electric Co. (up more than 200 per cent since 2009 to $22), Bank of America Corp. (up more than 250 per cent to $11.50), Boeing Co. (up more than 145 per cent to $75) and Exxon Mobil Corp. (up more than 35 per cent to $90). Moreover, many of those same corporations cut costs to the bone during the recession and are now more profitable than ever. “They’re sitting on tons of cash,” Acampora says. And that suggests a flurry of market-driving activity—mergers, leveraged buyouts and IPOs—once executives are convinced the economy is solidly back on its feet.

That hasn’t happened just yet, but there are nevertheless early signs the all-important U.S. economy has turned the corner. Housing prices in November enjoyed their biggest jump in six years, up 5.5 per cent, according to the closely watched S&P/Case-Shiller Index. Meanwhile, the U.S. Labor Department reported that employers added 157,000 jobs in January. The recovery has been bumpy, to be sure, but that’s to be expected when you’re trying to lift the world’s largest economy out of a generational funk, Johnson says. “It’s like turning a cruise ship around in a river—there’s all this back and forth before you have the desired effect.”

Nor is it just a U.S. story. In Europe, there’s growing confidence that the eurozone crisis is now under control. Unemployment remains at a record high of 18.7 million, but there are reports of more hiring in specific sectors, including energy and health care. Albert Edwards, the usually bearish chief global strategist for Société Générale, was quoted by the Financial Times as saying it was a “once-in-a-lifetime opportunity” to buy European stocks, a statement the newspaper described as a rare capitulation by a notorious “perma-bear.”

Canada’s economic outlook is improving, too, thanks to the U.S. recovery, although the gains are likely to be less impressive, since the country didn’t suffer as badly during the crisis. There also remain concerns about the country’s overheated housing market and the impact of an expensive loonie on exports. A recent report by Macquarie Private Wealth argued that slumping commodity prices mean Canadian markets are likely to lag behind those in the U.S. this year.

You can hardly blame average investors for wondering if it’s all a little too good to be true. A recent survey of investor sentiment by the American Association of Individual Investors found that the number of people who described themselves as “bullish” fell by 4.3 percentage points last week to 48 per cent. Meantime, there’s no shortage of analysts warning that the recent bull run is at risk of overshooting. Recent data showed the U.S. economy shrank unexpectedly during the fourth quarter of 2012, the first contraction since the recession ended. “To ignore this is folly,” Douglas Coté, the chief market strategist at ING Investment Management, recently told Reuters. “Certainly this market could continue to move forward, but ignoring the fundamentals is not something I would counsel my clients to do.”

Even those who believe a decade of market growth is on the horizon admit it won’t be a straight line. “In the short term there will be volatility,” says George Athanassakos, a professor at the Richard Ivey School of Business. “But you shouldn’t panic, because what happens is people panic and they buy high and sell low. You have to be more disciplined.”

Indeed, the biggest driver of the stock market over the next several years, according to the bulls, is likely to be investors themselves. Many observers are talking about a “Great Rotation” as pension funds and other big institutional players begin moving hundreds of billions out of low-yielding bonds and putting it back into stocks, driving up share prices. “The beginning stages of a great rotation in the markets create opportunities for cyclical and undervalued asset classes poised for recovery,” wrote economists at Bank of America in their 2013 outlook. Moreover, it’s believed that once all that capital begins flowing back into stocks, it’s going to be difficult to stop. “There’s this feeling of the bull train leaving the station,” says Johnson, pointing to the experience during the 1990s when everyone piled into mutual funds and average investors opened accounts with discount brokerages. “People really hate being left behind.”

But while flows back to equity funds have increased in recent weeks, it still represents a drop in the bucket compared to the hundreds of billions pulled out worldwide, including some $215 billion last year. There are also those who argue the true fallout from the 2008 financial crisis has yet to be fully felt. Harry Dent, an author and financial newsletter writer who forecast Japan’s economic collapse, says the U.S. economy is in a similar “coma” and is being kept alive through massive amounts of stimulus. Dent has warned of a stock market crash later this year that will last for a year and a half. He cites retiring baby boomers as another reason for worry, arguing they will dramatically cut back their spending as they leave the workforce, which could be bad news for the economy as a whole.

Ironically, Acampora says the best thing that could happen right now is a stock market correction. If shares take a hit only to recover, investors can be more confident the bull market is for real. “When bad news can’t take you down, that’s good news,” he says. “You know how a classic bull market ends? With greed and speculative junk. You think we’re there? Look at the financials, or GE. Or how about Alcoa, the largest aluminium company in the world—the stock is just $8. Buy it and give it to your kids when they graduate. This is fabulous stuff, but people just don’t believe it yet.”