For many young Canadians, home won’t be a house

Canada is building fewer single-family homes and pricing young people out of their communities—the sort of housing inequality could take us down a dangerous path

A construction worker shingles the roof of a new home in a development in Ottawa on Monday, July 6, 2015. Experts say measures introduced by the Ontario government to cool the red-hot housing market are likely to leave a lot of the buyers on the sidelines as they await to see the impact of the changes. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Sean Kilpatrick

Share

It’s probably time for Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to tell his young followers that the “Canadian dream” no longer comes with a lawn.

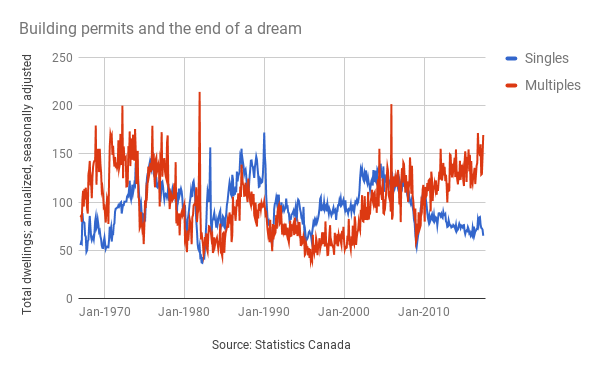

Last week, Statistics Canada reported a big drop in the issuance of building permits for single-family homes in cities with populations greater than 10,000. Municipalities in June granted permissions for such structures at a seasonally adjusted rate that would yield 65,100 units in a year, the slowest pace since April 2009 and one of the weakest on records that date to 1960.

The decline is noteworthy because you’d think the stars were aligned for a boom in the construction of dream homes: the economy has been churning out jobs steadily for a year, real-estate prices are high, and interest rates are low. There should be lots of incentive for everyone involved to build, borrow, and buy. Yet that’s not what’s happening. Those high prices have become too much for normal people, especially in Vancouver and Toronto. Tighter lending standards are also forcing dreamers out of the market. And perhaps more importantly, city officials remain stingy with land and permits in the places where most people want to live. “Toronto is a gateway for new immigrants,” Quentin D’Souza, who runs a couple dozen rental buildings in the Greater Toronto Area, told me earlier this summer. “We don’t produce enough new housing for all of those people.”

Since housing is mostly a local matter, you might be wondering why we need to drag the Prime Minister into this.

The answer depends on whether you think the federal government can play a catalytic role in forcing local authorities to confront national issues. Most (not all) agree that income inequality is one such issue. Trudeau certainly does. There is little that he or his cabinet ministers do that isn’t justified by supporting the “middle class and those seeking to join it.” More generous childcare benefits, middle-income tax cuts, multi-billion-dollar infrastructure programs, and new free-trade deals all are necessary to keep Canada from becoming an unequal society, the federal government suggests.

All that is fine. Yet the main thing that is turning Canada into a more rigidly class-based society is the real-estate boom. For whatever reason, most Canadians see a mortgage as preferable to paying rent and maxing out their RRSP deductions and TFSA limits. But in most cities, a decent house is now something only rich people can afford. Vancouver is the world’s third-most unaffordable city, after Hong Kong and Sydney, respectively; and Toronto is now the 13th most unaffordable, behind a group of usual suspects such as Auckland (fourth), San Francisco (ninth), and London (12th), according to the latest Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey. This is not the company that a country that believes in spreading the wealth ought to be keeping. If you don’t think the housing boom is causing angst, then you missed the excellent reporting of Joe Castaldo and Catherine McIntyre in Maclean’s earlier this year. As one half of a young couple that had been priced out of Vancouver told them, “You definitely feel like you’ve been left behind.”

Demographia, a St. Louis-based consultancy that opposes top-down urban planning, keeps its analysis of international housing affordability elegantly simple. It creates a “median multiple” by dividing the median house price in a given market by the median household income. Historically, Demographia says a multiple of three or less suggests normal people can afford a home. That’s the base of its affordability scale. The maximum is five or higher, which is the point at which the survey describes housing as “severely unaffordable.”

Vancouver’s multiple is 11.8 and Toronto’s is 7.7; both scores are a point higher than 2015, suggesting median homes prices in each city increased by the equivalent of a full year’s income in the span of 12 months. In fact, none of Canada’s major cities is affordable: Montreal, Calgary, and Edmonton all are “seriously unaffordable,” with multiples higher than four. Demographia says Ottawa is “moderately unaffordable,” with a multiple of 3.9. This represents a “sea change,” according to the report; until recently, affordability outside of Vancouver had been fairly stable since the 1970s. “The health of the housing market has been deteriorating rapidly in Canada,” the report states.

Trudeau and his ministers know the urban middle- and upper-middle-class Canadians that form the core of their political constituency are sensitive about housing. At a semi-private speech in Montreal this spring, Finance Minister Bill Morneau said that as a member of Parliament and a Cabinet minister, he felt Canadians were “counting on you to ensure their home keeps its value.” Recall “David,” the everyman who appeared on the first page of Morneau’s first budget in 2016: “Though he loved the community he lived in as a child, when it came time to buy his own family home, [David] had to look elsewhere. His old neighbourhood simply wasn’t affordable.” Among the highlights of this year’s budget was a promise to spend $11.2 billion on affordable housing.

Still, it’s fair to ask whether Trudeau has any desire to bring real-estate prices back down to Earth.

Doing so would please the men and women Castaldo and McIntyre wrote about, and surely would be welcomed by those “seeking” the trappings of the middle class. At the same time, any attempt to depress prices would anger anyone who already owns a home, a massive voting block, considering ownership rates now approach 70 per cent. That could be why Morneau talks of “protecting” home values, rather than making housing more affordable. The federal government’s housing strategy will help some people, but it will do nothing to alter price dynamics, especially as the money will be spent over a decade. Morneau initiated regulatory changes that make it more difficult to get home loans, but he so far has stayed away from sacred housing sops, such as the capital-gains exemption on primary residences and the ability of first-time buyers to use their tax-protected savings to purchase homes.

Demographia says Singapore and New Zealand are the only two countries that appear to be taking the issue of housing affordability seriously. (The organization’s analysis is based on assessments of those two countries, along with Australia, Canada, Hong Kong, Ireland, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the U.S.) New Zealand is the more instructive example; its politicians appear to have accepted that home prices are off the charts for lack of supply. Space is dear on a tiny island, but New Zealand authorities have constrained it even more by constraining development. Canada is as guilty of this as any jurisdiction, whether it be restrictive zoning requirements in Vancouver or Ontario’s safeguarding of green space in and around the Greater Toronto Area. The response of governments in Ottawa, Victoria, Vancouver and Toronto to the threat of a housing bubble has been almost entirely focused on gently squeezing demand rather than encouraging more supply.

By no means do I mean to give Demographia the final word on the subject. The outfit submits that sprawling Dallas-Fort Worth is a more livable city than Toronto because Dallas’s inhabitants tend to have shorter commutes to work. That car-loving conclusion gives away Demographia’s ideological bias. No doubt, an interesting argument could be had about whether a future of self-driving, electrically propelled automobiles could be as clean and efficient as better public transit. But only the purest free-market disciples would condemn attempts to make cities denser.

Canada’s bigger municipalities are headed this way. In recent years, they have been encouraging developers to build up, rather than to spread out. Cities issued permits for multi-family dwellings at a seasonally adjusted annual rate of 169,600 in June, the fastest since October 2016. If we assume those permits turn into holes in the ground, Canada is putting up apartment complexes at the fastest rate since the early 1970s.

That’s probably a good thing. It will increase the odds that urban Canadians will at least be able to find a suitable place to live. But will it make people happier? Ideology aside, Demographia has a point when it argues that Dallas beats Toronto also because more people in the Texas city can afford to buy a home. Canadians might prefer urban planning that put “people” ahead of “place.” Take another look at the historical pattern for building permits in that chart above. There was a time when Canada built more single-family homes than multi-family units. The relationship has reversed, and the gap between apartment living and the prospect of backyard barbecues has never been wider in Canada’s cities.

Does any of this really matter? Robert Shiller, a Nobel laureate in economics, thinks it does. The Yale University professor says societies could rue allowing people to be priced out of their communities. “With people of various income levels increasingly divided by geography, income inequality can worsen and the risk of social polarization—and even serious conflict—can grow,” Shiller said recently in an op-ed for Project Syndicate. Inequality of income begets inequality of opportunity, which begets societal tension and political volatility. See: Donald Trump’s America.

A generation of Canadians that took space for granted is now discovering that their future will be measured in 900 square feet or less. That needn’t be a big deal, except as Castaldo and McIntyre showed earlier this year, it is a big deal for a lot of people. Will those people adapt and make the most of their lawn-less futures? Or will they grow to resent the lucky ones who owned homes at the beginning of the boom and the politicians who failed to keep prices under control?

At the moment, it appears Trudeau, Morneau and their counterparts in the provinces and on municipal councils are most concerned with helping the lucky ones. That’s good news for the existing middle class. But if you are seeking to join it, you have reason to be disappointed.