Oil sands cost inflation coming back to bite us now

Rising oil prices since the early 2000s have hidden a lot of sins in the oil sands

Share

In June, 2006, Canada’s National Energy Board published their outlook for Opportunities and Challenges in the oil sands through to 2015. Today, with the oil sands industry watching the ever-falling oil price with increasing trepidation, looking back on the forecasts in this report should give us all pause for thought about what’s gone so badly wrong.

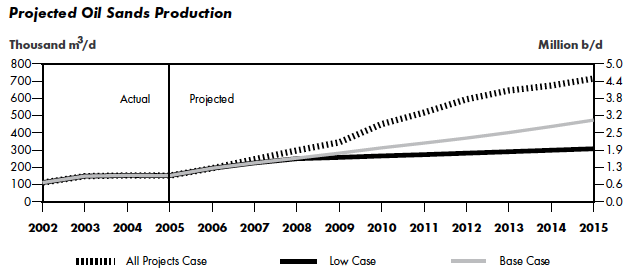

When the NEB set about forecasting oil sands production to 2015, they looked both at the total projects announced as well as what they considered to be the most likely base case forecast, as well as a low case. In what they considered to be the most likely scenario, we were told to expect 3.2 million barrels per day by 2015.

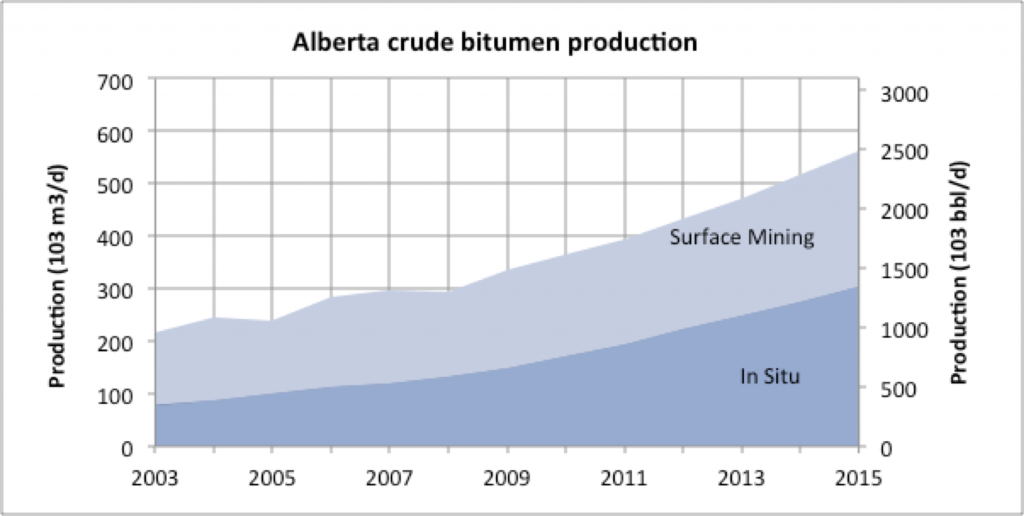

How has production actually evolved? If you look at the most recent forecast from Alberta’s Energy Regulator (their 2014 forecast should be released shortly), you’ll see that we are likely on pace for about 2.5 million barrels per day by 2015 – a miss of about 700,000 barrels per day in bitumen production from the 2006 base case, and about midway between the low and base cases.

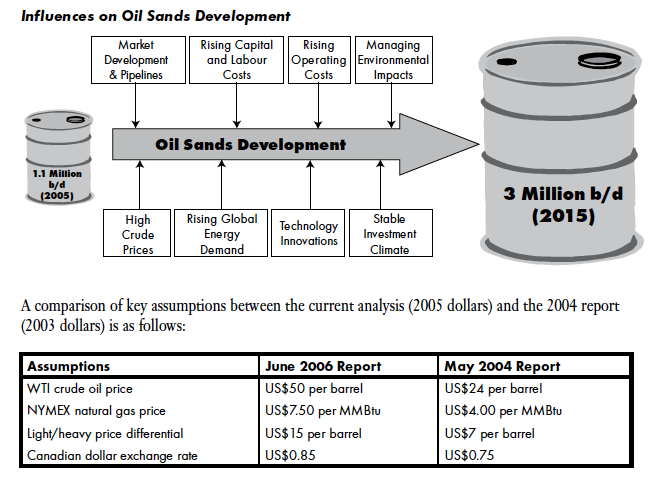

In and of itself, missing a production growth forecast by 40 per cent is notable, but this becomes much more of an issue when you look into the details of what was assumed in the NEB’s numbers, and what we’ve seen since. In the 2006 report, the NEB included the following graphic which lays out their key assumptions:

The environment in which the NEB was expecting this growth to occur is eerily similar to today on most dimensions – $50 WTI prices, an 85 cent Canadian dollar exchange rate and a $15 heavy to light differential- and worse from an oil sands perspective than we’re seeing today in terms of gas prices. In the intervening years, with the exception of the 2008 financial crisis, oil prices have been, in real dollar terms, higher than the NEB forecast and gas prices have been lower, even adjusting for the stronger Canadian dollar and wider heavy-light differentials seen over the past few years. In other words, we’ve missed the growth projections in an environment which was markedly better for oil sands than that assumed in the forecast. Today, we’re back to the conditions the NEB was envisioning, and we’re in a panic.

What changed? Costs. If you dig a little further into the NEB report, you’ll see where things went terribly wrong. The NEB report forecast that we could build oil sands projects at a pace much higher than we have been, while maintaining costs per barrel which would be the envy of almost any oil producer today – the 2006 report suggested that a new oil sands projects would be viable at WTI prices (adjusted for inflation to current dollars) of US$20-25 per barrel – over 50 per cent lower than the low prices we’re seeing today. The NEB estimated that operating costs, again adjusted to today’s dollars, would be in the range of $12-$16, and that’s with natural gas prices at levels over double today’s prices in inflation-adjusted terms. The NEB forecast that the cost to build a new oil sands mine would be $20,000 per barrel per day of capacity. Suncor expects to spend over $84,000 per barrel per day to build Fort Hills, and Imperial Oil spent well over $100,000 per barrel per day to build Kearl. The NEB expected that we could construct the additional 2 million barrels per day of capacity for about $125 billion dollars. Actual capital expenditure, combined with the expenditure forecast for 2014 and 2015 by the Alberta Energy Regulator will see expenditures close to double that – approximately $200 billion – between 2006 and 2015, while installing 40% fewer barrels per day of capacity.

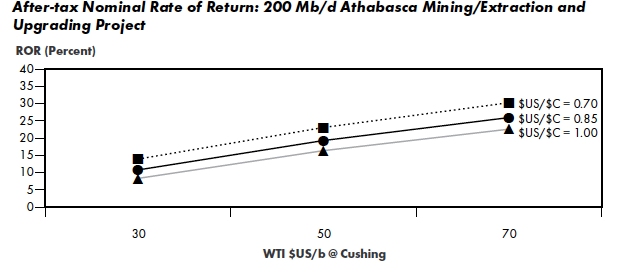

When you look at the conditions the NEB was forecasting, oil sands projects looked incredibly robust at prices we now consider to be panic-inducing. Consider the figure below which shows expected returns from an integrated oil sands mine and upgrader, similar to the expansion now under construction at CNRL’s Horizon Project, under various combinations of the US dollar and the exchange rate. At today’s prices, of approximately $50 US WTI prices and an 85 cent US dollar, the 2006 report would have expected a rate of return on capital invested for such a project of about 20 per cent. At today’s capital and operating cost, such a project would likely have an expected rate of return in the one to three per cent range.

Perhaps the current price shock will give us pause – pause to consider what an Alberta with more control on the pace of development and without the inflationary impacts which come with open-access development would look like. Had we been able to maintain costs at even double those considered by the National Energy Board, we’d have seen substantially higher taxes, royalties, and profits per barrel, although of course on fewer barrels, and we’d find ourselves much better-positioned to weather the downturns in oil prices which inevitably come. Perhaps it’s time for the Alberta government to acknowledge that it’s not optimal to simply leave the market to decide the pace of oil sands development: the government is and must be a key part of the market as the representative of the owners of the resource, the regulator of extraction and the construction of new projects, and the administrator of the royalty regime. Rising oil prices since the early 2000s have hidden a lot of sins in the oil sands, and some of those sins are going to cause a lot more pain in Alberta than need be the case for as long as this most recent drop in prices last. Perhaps, this time, we’ll learn from our mistakes.