23 charts to watch on inflation and the economy in 2022

Chart Week 2022: Canadians spend more on homes than Americans, food prices will reach new heights, why rising interest rates will be in our future, and more

Share

For Maclean’s eighth annual chartstravaganza, we’ve once again asked dozens of economists and analysts to ponder the year to come, and choose one chart that will help define Canada’s economy in 2022 and beyond, and explain this outlook in their own words.

This year, we’ve decided to release the charts over several days, making this more of a Chart Week than a one-day data binge. We’ll also cover jobs and income, COVID, energy and—yes, don’t worry—real-estate outlooks.

The things that divide us

Beata Caranci, chief economist, TD Economics

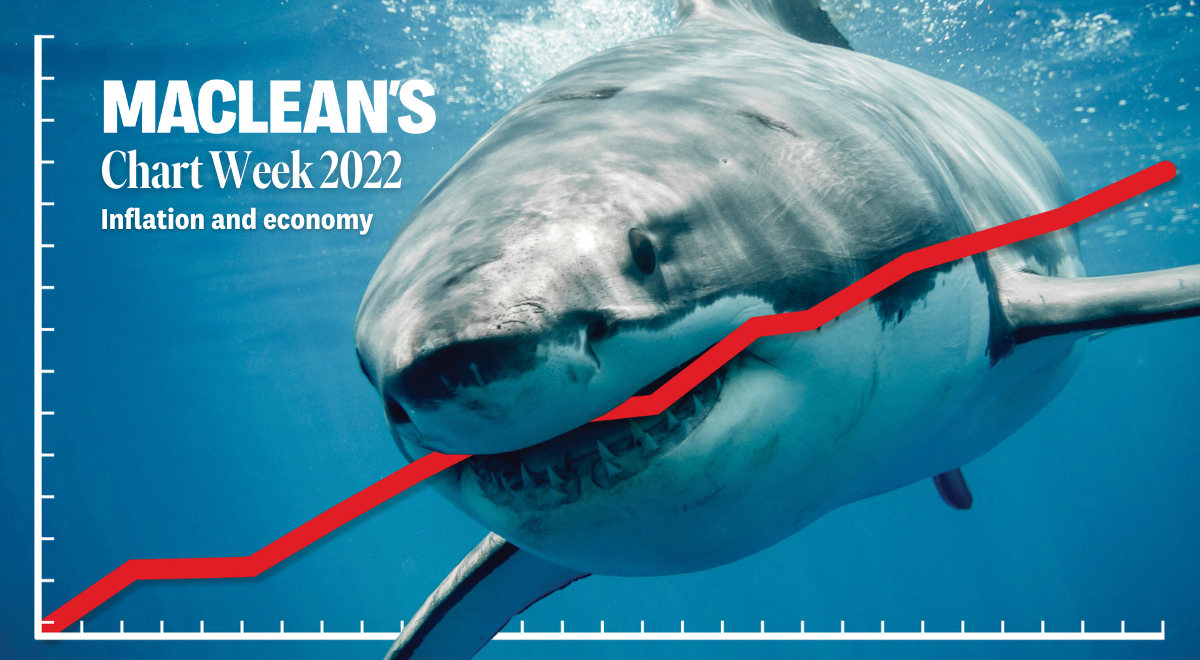

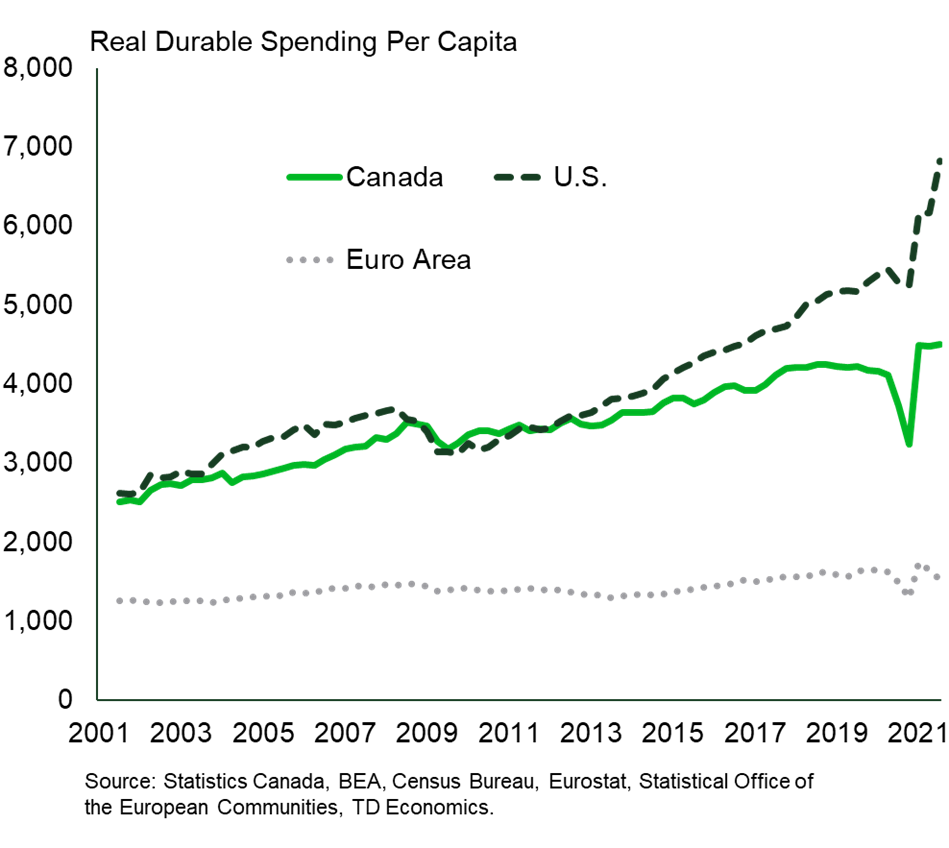

Canadians often identify with economic narratives to the south. But, when it comes to inflation, Americans are more exposed to bottlenecks than Canadians because of their high tendency to “spend more on things.” These products are more linked into international supply chains that compound the impact from supply chain dislocations. Canadians import their exposure due to the high trade relationship, but it isn’t the primary domestic area of concern.

In contrast, Canadians “spend more on homes” and this embeds greater interest-rate sensitivity than our American counterparts. Nuances between countries create a different transmission of risks depending on their origin. So when people note that the pandemic is pressing on inflation, it assumes there’s not a precondition or, if so, it carries minimal influence. But, not all dynamics can be blamed on the pandemic. For instance, the U.S. trucker shortage predates the pandemic and is not going to suddenly resolve in the next six months as pandemic risks recede. “Normalization” for the U.S. doesn’t alter the fact that Americans maintain higher spending on things relative to other countries, even in a normal environment. The risks stemming from supply and logistics tensions will be hard to solve in the absence of a resetting of demand into a much slower (but sustainable) growth pattern.

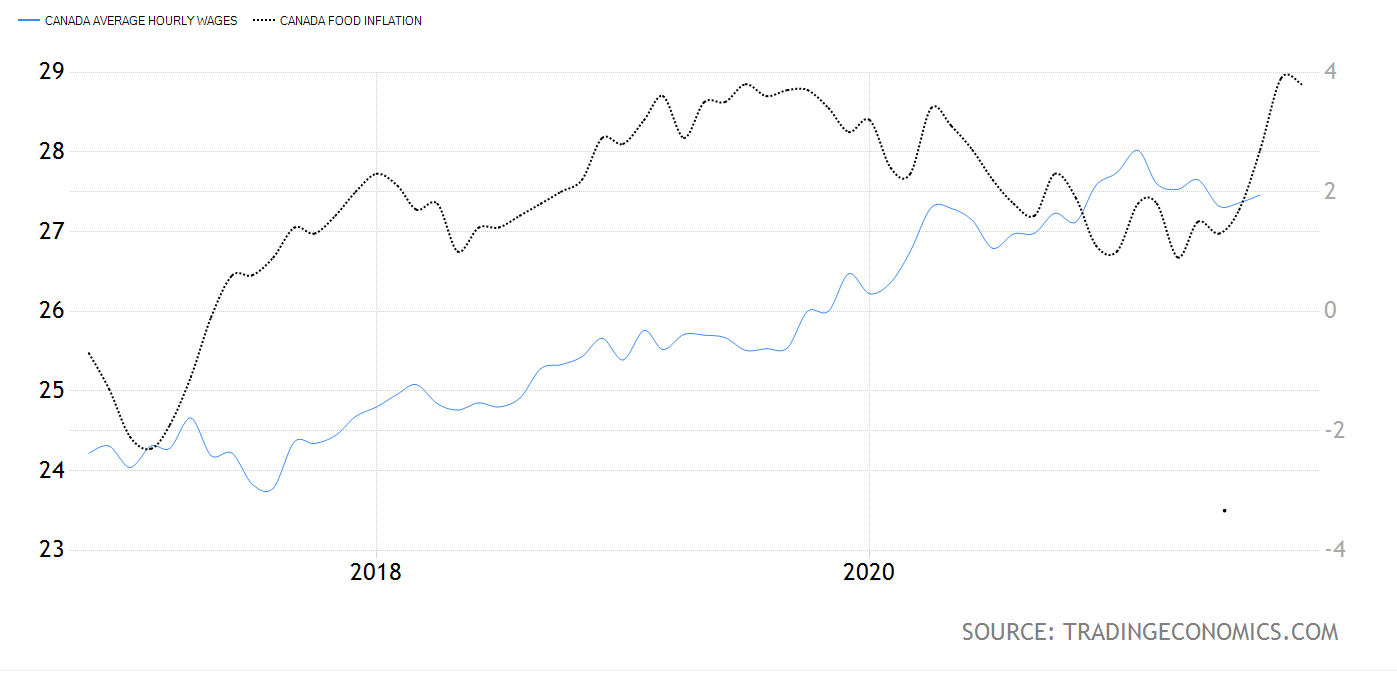

Eating into our paycheques

Sylvain Charlebois, director, Agri-Food Analytics Lab, Dalhousie University @FoodProfessor

According to the UN’s Global Food Security Index, Canada now ranks 24th in the world when food affordability is measured. In 2020, Canada was 18th. Food inflation reached new heights in 2021 and will likely continue to be an issue for Canadian families. Meanwhile, salaries have barely increased since the start of 2021. Unlike the “great resignation” we are seeing in the United States in recent months, Canada is experiencing its own “great protest”. Food inflation is not necessarily an issue unless it outpaces average wage increases. And this is what happened this year. Despite the fact that we are expecting higher food prices again in 2022, wages need to go up to give Canadian families a fighting chance.

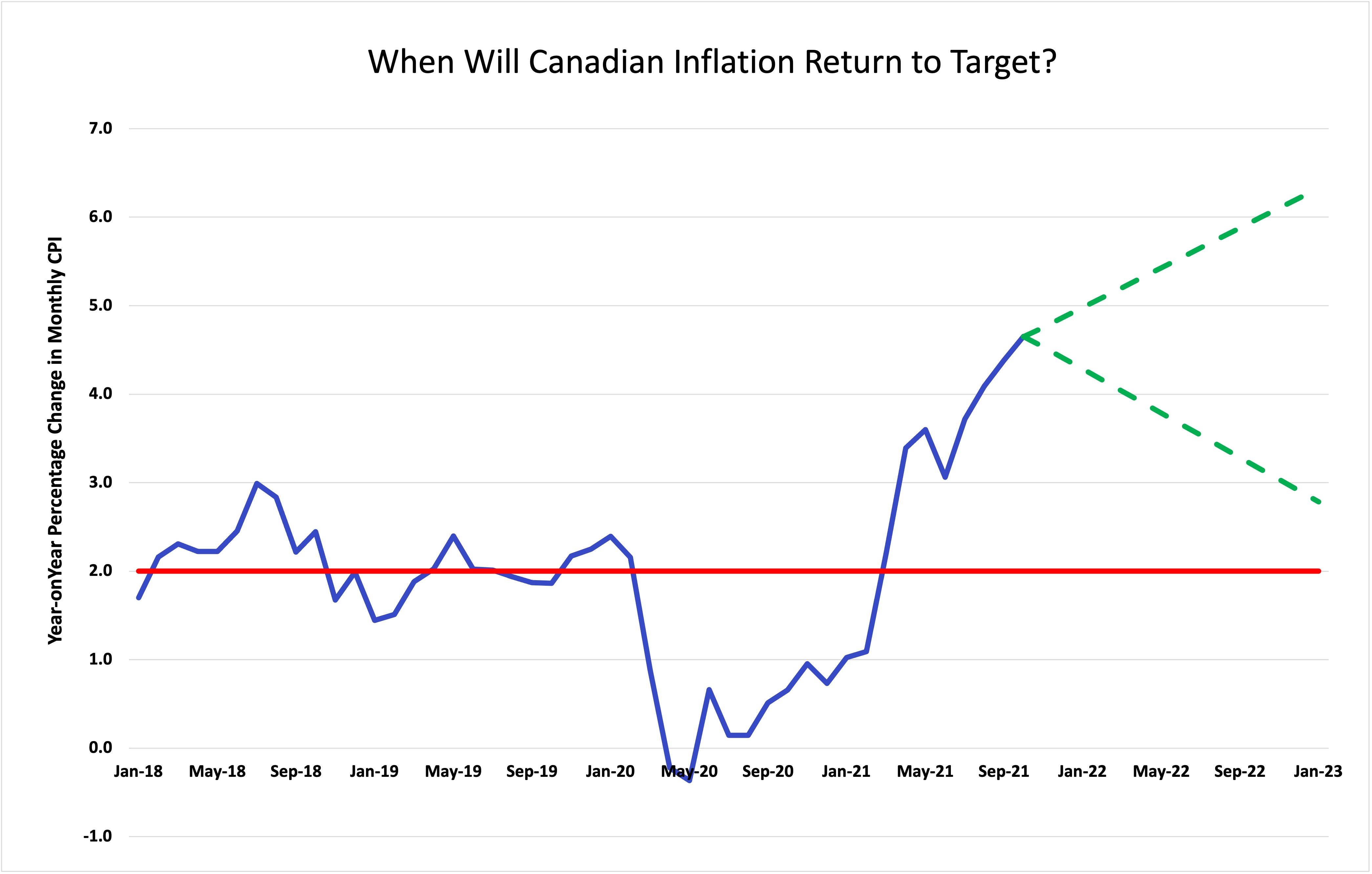

When will inflation return to target?

Christopher Ragan, director, Max Bell School of Public Policy, McGill University @ctsragan

In the years leading up to the pandemic, Canadian inflation was relatively stable and close to its formal target of two per cent. With the onset of COVID-19, however, the economy entered an enormous recession and inflation fell, with the average throughout 2020 being below one per cent. But by March 2021, the year-on-year percentage change in the monthly CPI exceeded two per cent and has been rising ever since.

In early 2021, the central explanation for inflation’s rise was mostly a quirk of the data—that measured inflation was catching up from the very weak price behaviour seen during the early months of the pandemic. By this logic, the uptick in inflation would be very short-lived. By the summer and fall, however, it was evident that the inflationary pressures were stronger and more fundamental, coming from the combination of widespread disruptions in global supply chains and the pent-up consumer demand that accompanied a re-opening of the economy made possible by widespread vaccinations.

What will happen next? If the supply-chain disruptions and pent-up demand are truly transitory phenomena, as argued by the Bank of Canada, then inflation may return to the two-per-cent target sometime in 2022 or 2023. But even if these phenomena disappear relatively soon, there is another, more important danger. The Bank of Canada has provided a massive amount of monetary stimulus to the economy over the past 18 months. As the economy makes its way back to its full productive potential, this stimulus will need to be pulled back in a timely manner to prevent classic “demand-push” inflation. Rising interest rates will almost certainly be a part of our near future.

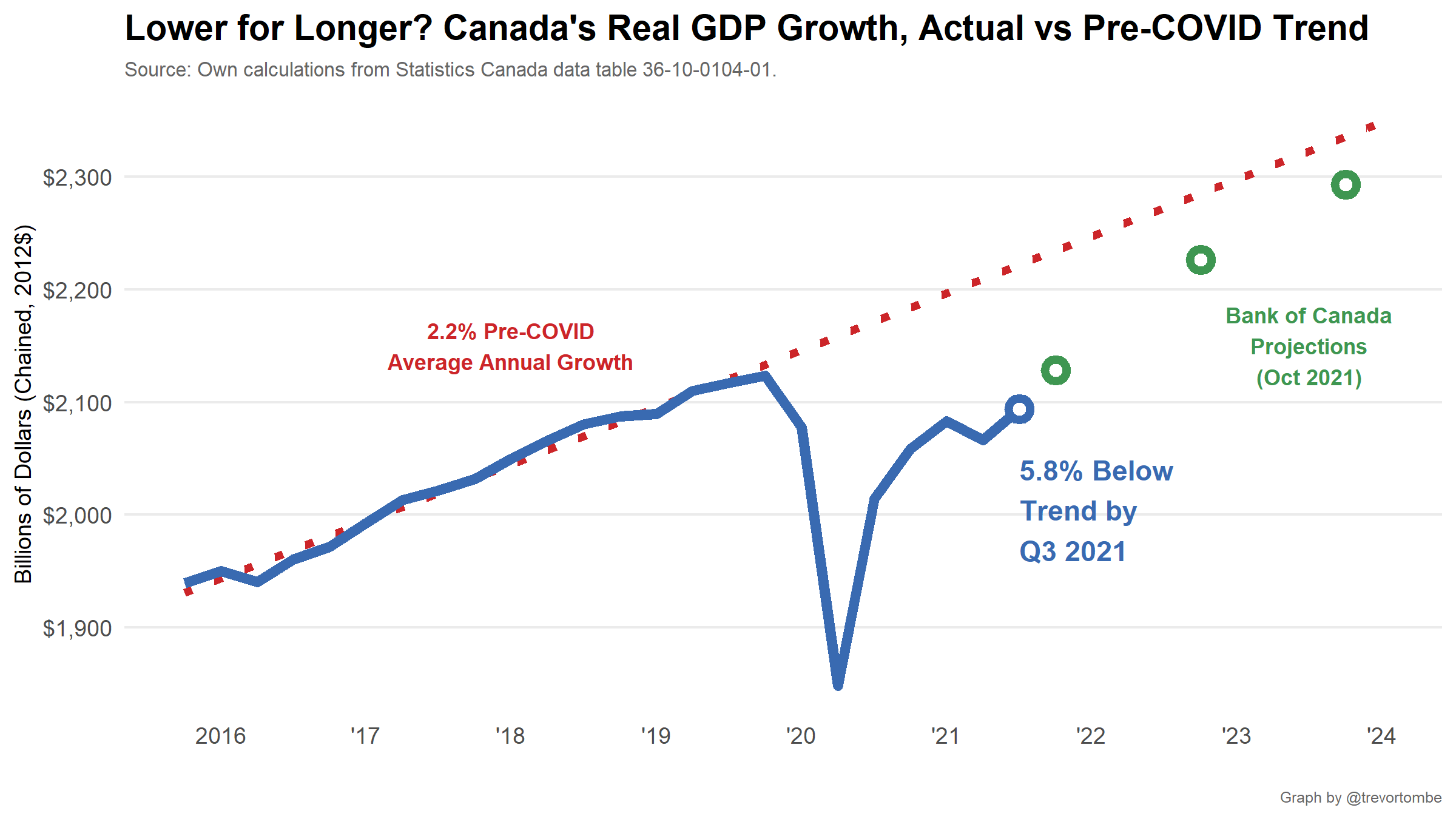

Will COVID’s economic damage linger?

Trevor Tombe, professor, Department of Economics, University of Calgary

The pandemic was not only a public-health crisis but also the source of the sharpest economic contraction in Canadian history. The pace of recovery since those dark early months, however, has been nothing short of remarkable. By September 2021, the fraction of individuals employed was nearly back at pre-COVID rates and overall GDP nearly was. But challenges remain. Future growth may, unfortunately, be lower for longer. The Bank of Canada recently cut its forecast of “potential output” growth to approximately 1.6 per cent — down from prior forecasts and our pre-COVID trend. By Q3 2021, Canada was 5.8 per cent below its pre-pandemic trend (equivalent to $145 billion per year). Has COVID permanently damaged Canada’s economy? Or will workplace innovations (like remote work) and policy responses (like expanded childcare) boost productivity growth above its prior trend? Where our economy goes in 2022 will give early indications about which of these two possibilities may be likely. Our GDP relative to pre-COVID trends is therefore an important chart to watch.

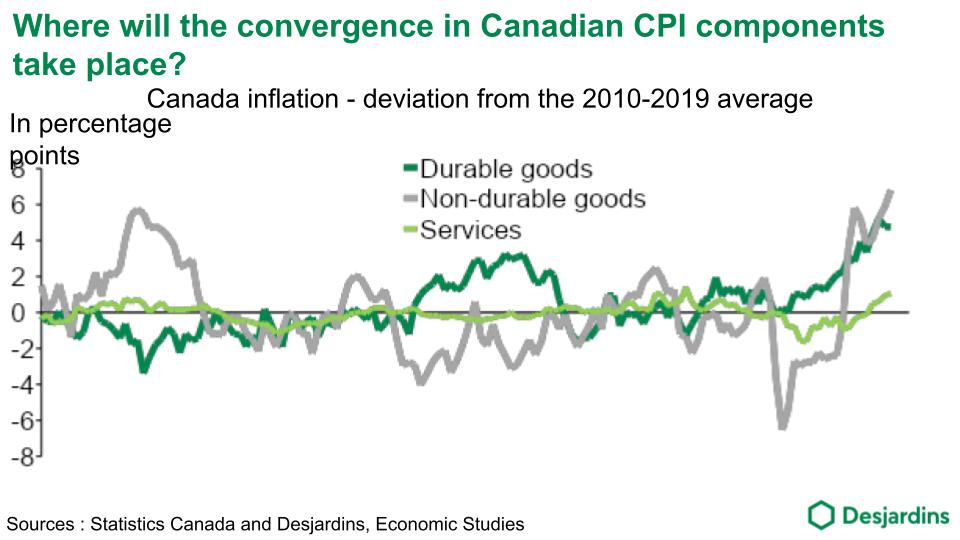

Goods news for people who love bad news

Jimmy Jean, chief economist, Desjardins Group

For inflation forecasters, the year 2021 could be as much of a year to forget as a year that will be forever remembered, depending on how one chooses to look at it. During the first half of the year, the pressure was clearly concentrated in goods, whereas, with a services sector still held back by lockdowns in the first half, services inflation was still below the average of the last cycle. The consensus narrative for the second half of 2021 contended that goods inflation would start cooling off, whereas the reopening would nudge services higher. The problem is that only the second part of that narrative proved correct.

So the question for 2022 is: where will the convergence take place? The transitory view has argued that it would occur on the way down, as inflation in goods eventually reverts to the mean. This scenario remains plausible, but we still lack clarity on the time horizon over which the reversion to mean should be taking place. Meanwhile, we have come to better appreciate the multitude of impediments that could impede supply further in 2022.

Meanwhile, in services, recovering demand as well as the high costs that businesses are facing on many fronts are skewing inflation risks to the upside. Pricing-power sentiment has rarely been stronger; as per the Bank of Canada, in Q3 2021, 37 per cent of businesses expected to increase their prices significantly over a 12-month period, up from only 11 per cent at the end of 2019. The intensification of this kind of inflationary psychology would imply more persistence than expected and could force the Bank of Canada into taking drastic steps—for better or worse.

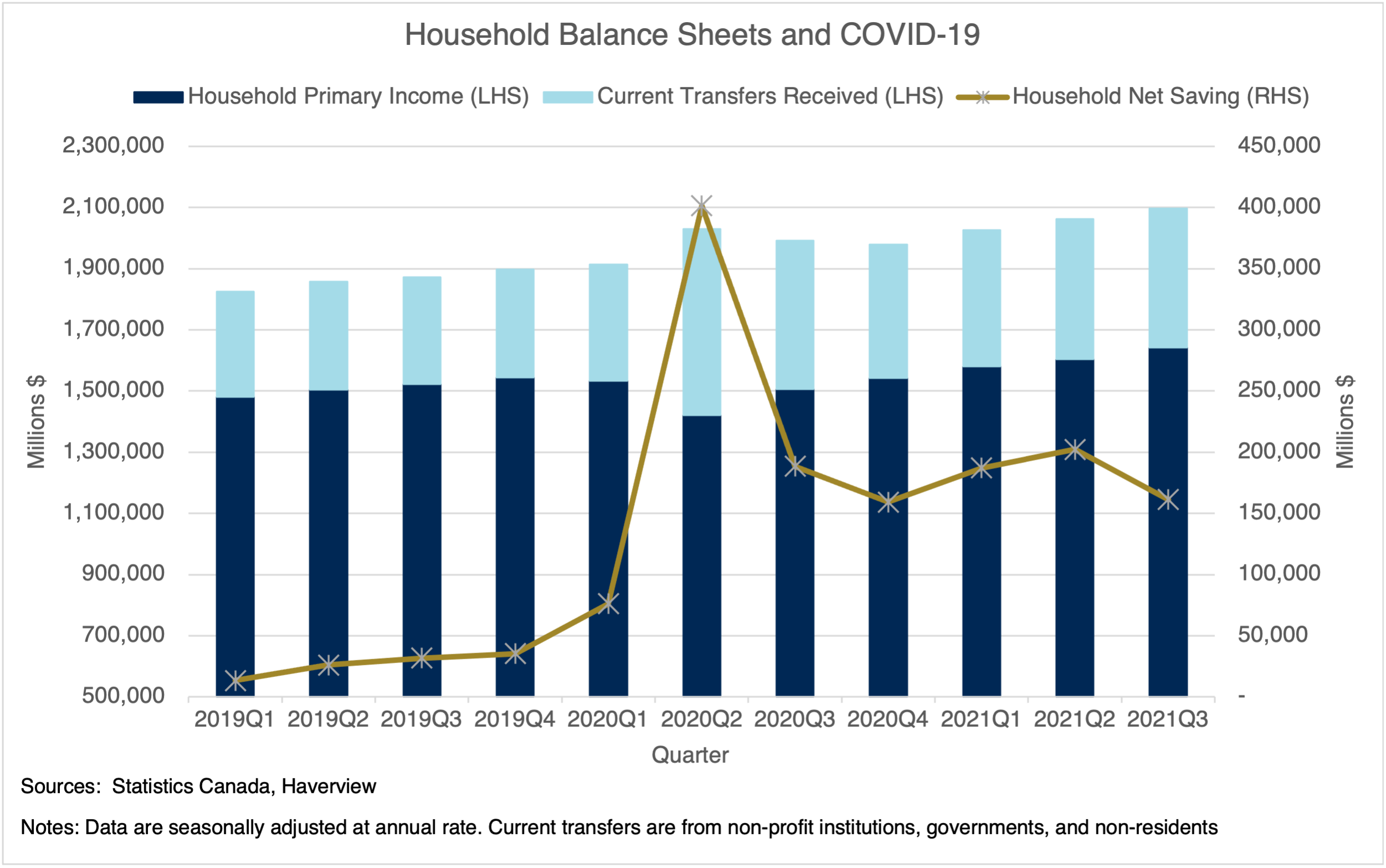

Household balance sheets and COVID-19

Kevin Page, president and CEO; and Aimeric Atsin, senior analyst, Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy, University of Ottawa

In these unusual times, there are many indicators to watch to better understand which way the economy may turn. Watch the evolution of household balance sheets. Net savings have been boosted by fiscal supports and some reduction of spending during the pandemic lockdowns. Going into the fourth quarter of 2021, net savings are up more than $100 billion. That is a lot of money in a $2.5-trillion economy and a recovery driven by consumption.

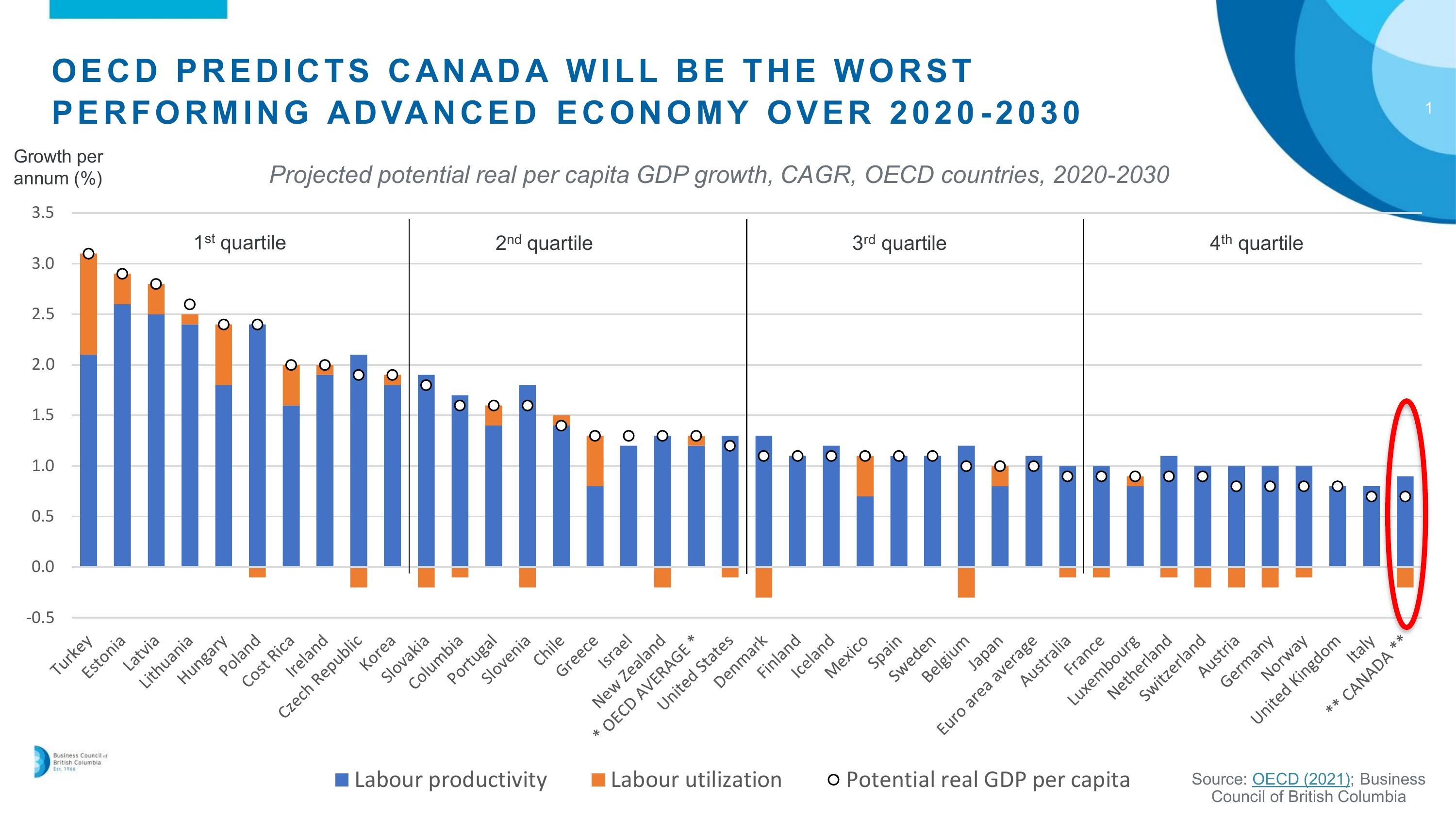

Low Canada

David Williams, vice-president of policy; and Jock Finlayson, senior policy advisor, Business Council of British Columbia

Ottawa’s economic growth strategy rests on four shaky pillars: accommodative monetary policy to support interest-sensitive sectors of the economy like credit, housing investment and durable goods consumption; expansive fiscal policy; record immigration levels; and a national child-care policy to expand the labour supply. The political class appears disinterested in raising productivity through higher business investment per worker, faster innovation adoption or scaling companies.

A recent OECD report offers sobering findings about whether Canadians can look forward to meaningful gains in average living standards. It predicts Canada can at best achieve real per capita GDP growth of only 0.7 per cent per year between 2020 and 2030, placing us last among advanced countries. Our prospects are poor because of feeble expected growth in output per hour worked (labour productivity) and a slight drag from hours worked per head of population (labour utilization).

The next decade is not an aberration. The same OECD report projects Canada will also post the worst economic performance among the advanced countries from 2030 to 2060, with per capita GDP increasing by just 0.8 per cent per year.

Past generations of Canadians entering the workforce could look forward to favourable tailwinds lifting real incomes over their working lives. That’s no longer the case. It is time for our governments to rethink their priorities and take steps to create the conditions to support a more productive economy.

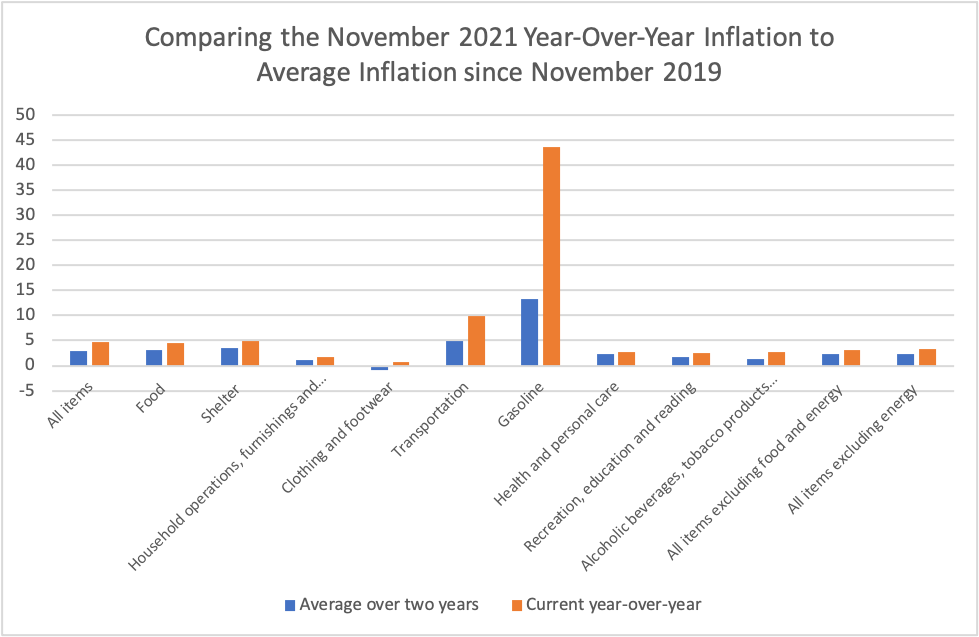

Behind the headline inflation rate

Mostafa Askari, chief economist, Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy, University of Ottawa

The current high inflation is partly due to the rise in oil and natural gas prices globally; partly to the pandemic-related supply chain issues and partly due to the fact that, last year, prices declined (the so-called base effect). This chart shows that when we compare the level of the Consumer Price Index of November 2021 to that of November 2019, the average inflation is only about 2.8 per cent annually rather than the 4.7 per cent headline rate. Moreover, underlying the current headline rate of 4.7 per cent inflation is about 44 per cent an increase in gasoline prices, totally because of the substantial increase in global oil prices.

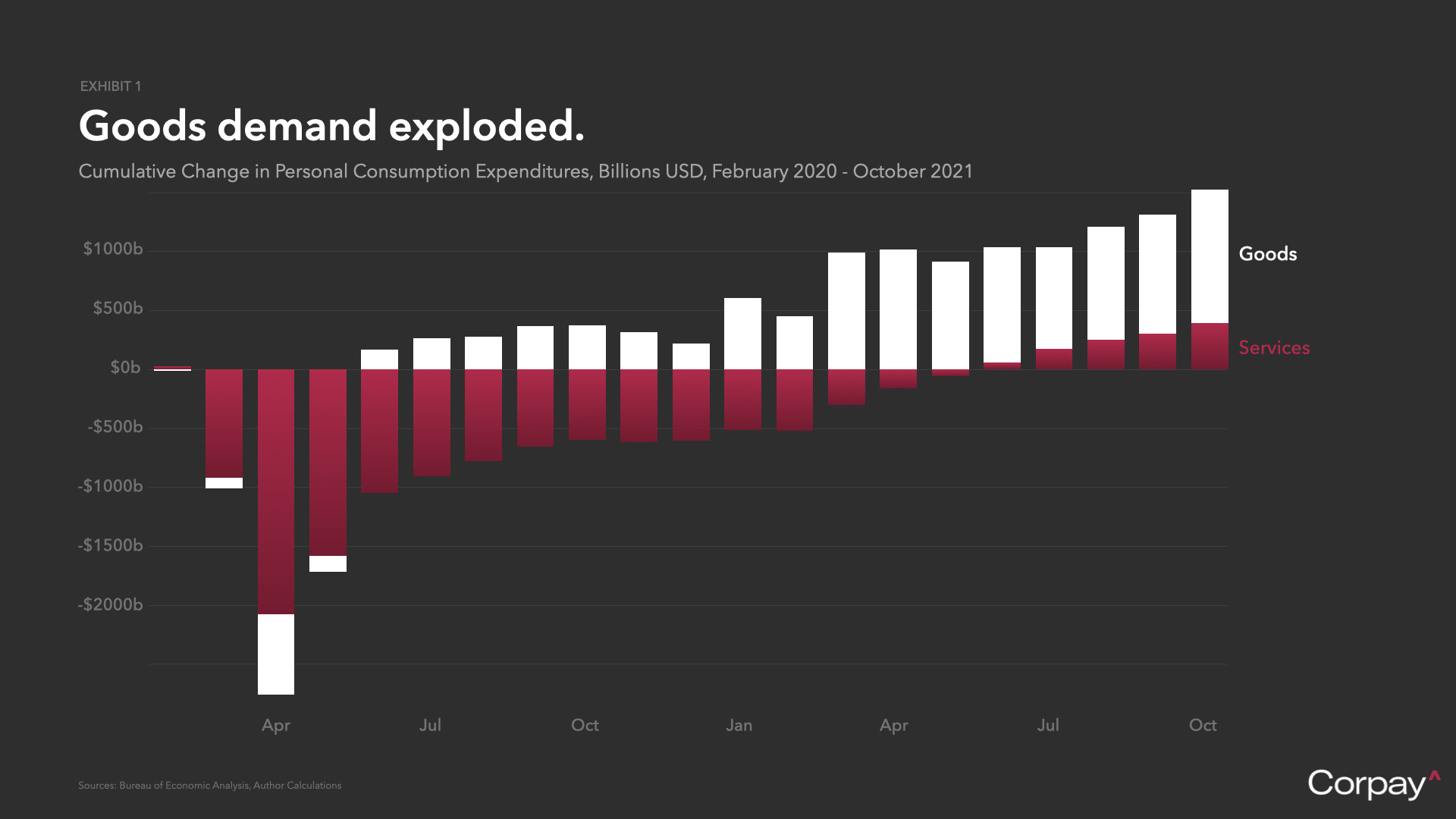

U.S. is buying. What will it cost us?

Karl Schamotta, chief market strategist, Cambridge Global Payments @vsualst

By putting trillions of dollars directly into household pockets over the last two years, the U.S. government reshaped the global economy. Flush with cash but unable to spend in person, American consumers splurged on tangible goods—from electronics to building materials—and put unprecedented pressure on pandemic-disrupted global supply chains.

The implications are profound. If the Bank of Canada raises rates, it could crush domestic demand without impacting the factors driving inflation. If U.S. consumers run down their savings and shift spending back to services, supply chains could suddenly become too full. And if political pressures limit the scope for further government stimulus, our re-engineered—and increasingly goods-focused—economy could struggle to adapt.

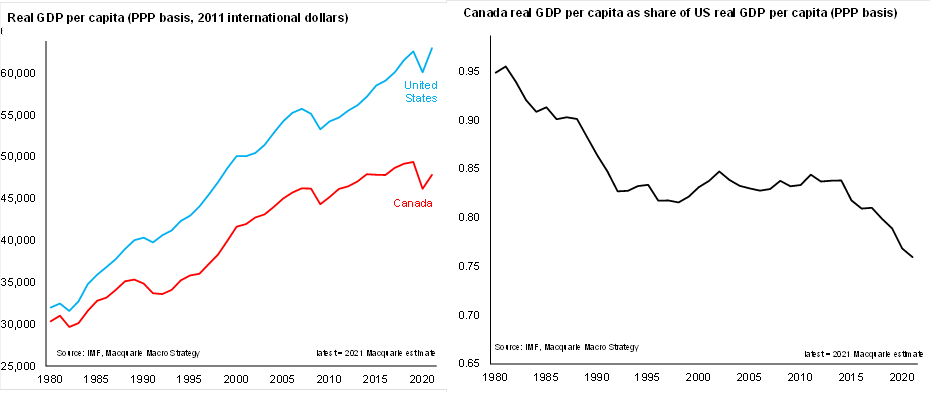

Falling further behind

David Doyle, head of North America strategy and economics, Macquarie Group

During the pandemic, Canada’s real gross domestic product has disappointed relative to the United States. This underperformance is even more severe when depicted on a per capita basis, reflecting the average standard of living in each country.

It continues a trend that has been in place for the past six years. Over this time period, U.S. real GDP per capita has risen by nearly eight per cent, while Canada’s has trended sideways. Put simply, Canada is falling further behind, as competitiveness has suffered due to meandering productivity growth.

Until recently, many households have felt insulated from these trends due to the wealth effect emanating from rising house prices. This period may now be coming to an end. Higher interest rates should slow house price gains, potentially significantly. Moreover, negative real-wage growth resulting from elevated inflation is likely to put household budgets under even greater pressure.

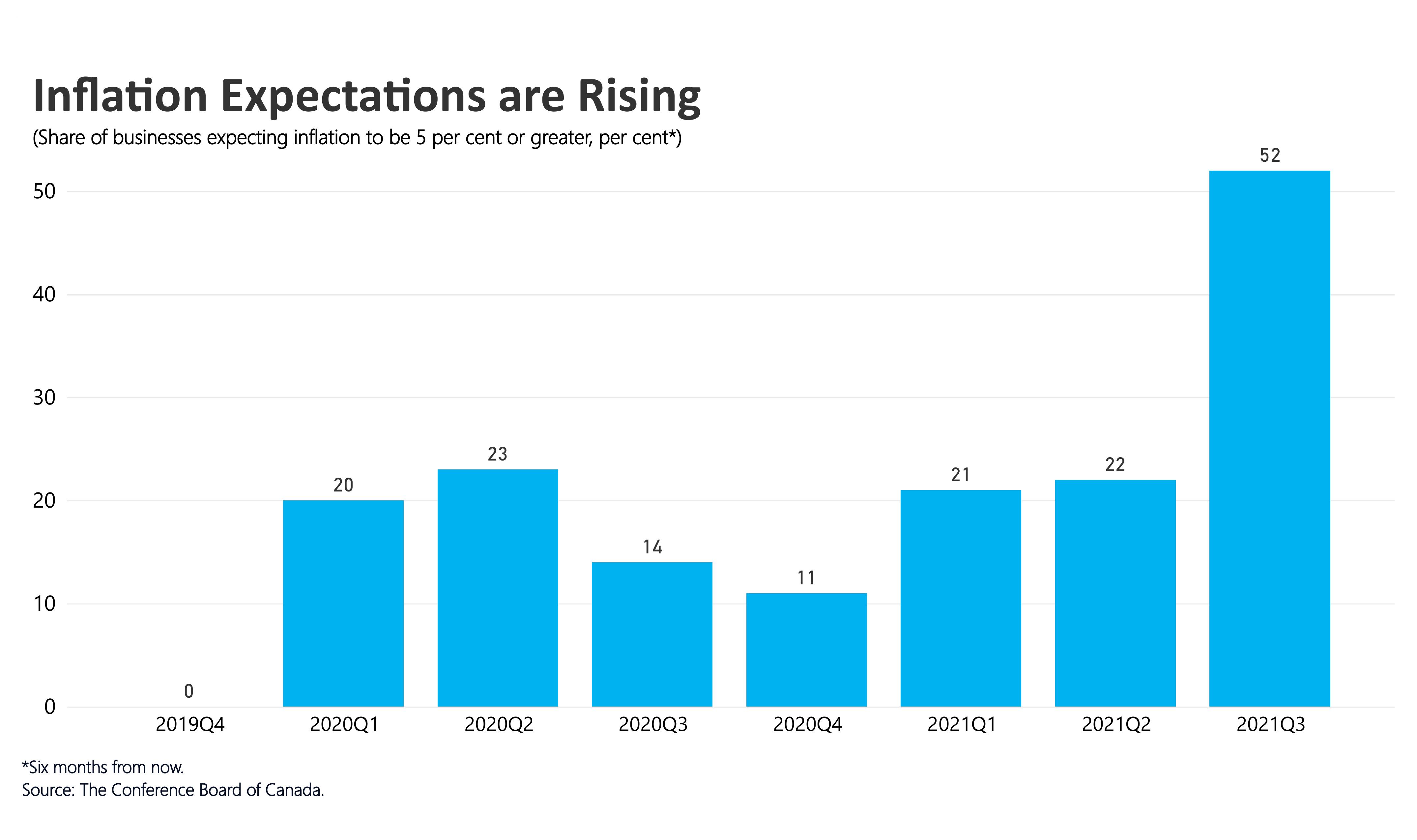

Inflated expectations

Sohaib Shahid, director of economic innovation, Conference Board of Canada

Canada’s inflation expectations are on the rise. The Conference Board of Canada’s latest index of business confidence shows that more than 50 per cent of businesses expect inflation to be five per cent or more six months from now. Moreover, a recent consumer survey by the Conference Board shows that almost 40 per cent of Canadians expect inflation to be five per cent or higher two years from now. We are closely monitoring inflation expectations because actual inflation partly depends on what people expect it to be. Higher expectations risk more inflation embedding into wage expectations and future prices. If an increasing number of people expect prices to rise in the future, higher inflation could become a self-fulfilling prophecy. And that would make the Bank of Canada’s job of keeping inflation within the one-to-three per cent target range even more difficult.

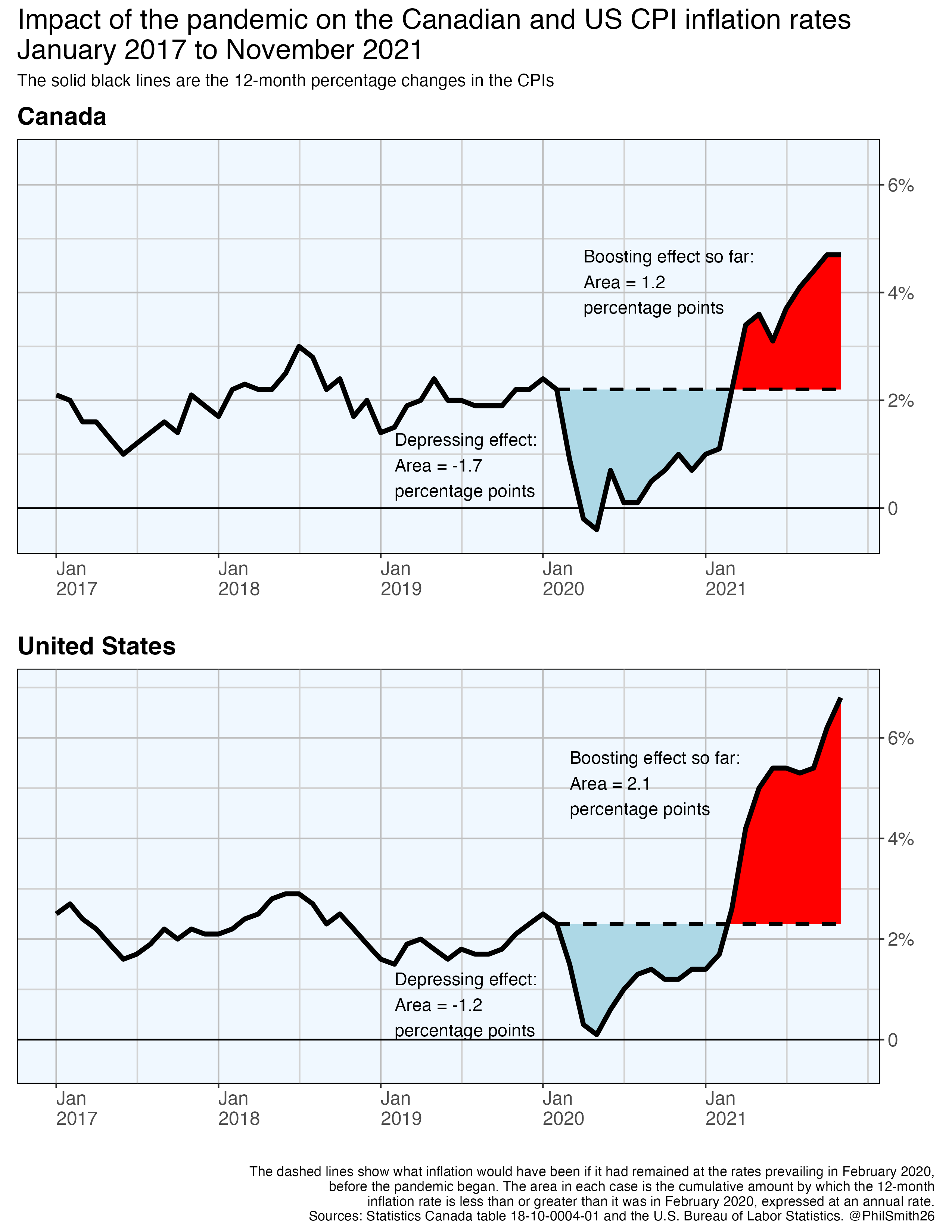

Inflation’s climb Stateside

Philip Smith, economist and statistician @philsmith26

Canada’s CPI inflation rate was depressed in the pandemic months following February 2020 by a cumulative 1.7 percentage points. In the United States, the corresponding impact was 1.2 points. Since early 2021, the recovery has boosted inflation in Canada by 1.2 percentage points, while in the United States the positive impact has been 2.1 points. As of November 2021, then, the pandemic has had a net negative (-1.7 + 1.2 = -0.5) effect on cumulative inflation in Canada and a net positive effect (-1.2 + 2.1 = 0.9) in the United States.

Canadians benefited from lower inflation when the pandemic began in 2020 and the economy sagged due to the shutdowns. Inflation then became higher in 2021 when vaccines were available and the coronavirus waned somewhat, allowing the economy to rebound. How long will inflation continue to run above the Bank of Canada’s one-to-three per cent target range and what will be the cumulative impact on the price level once inflation comes back down to a more normal rate? This is a vital question for 2022.

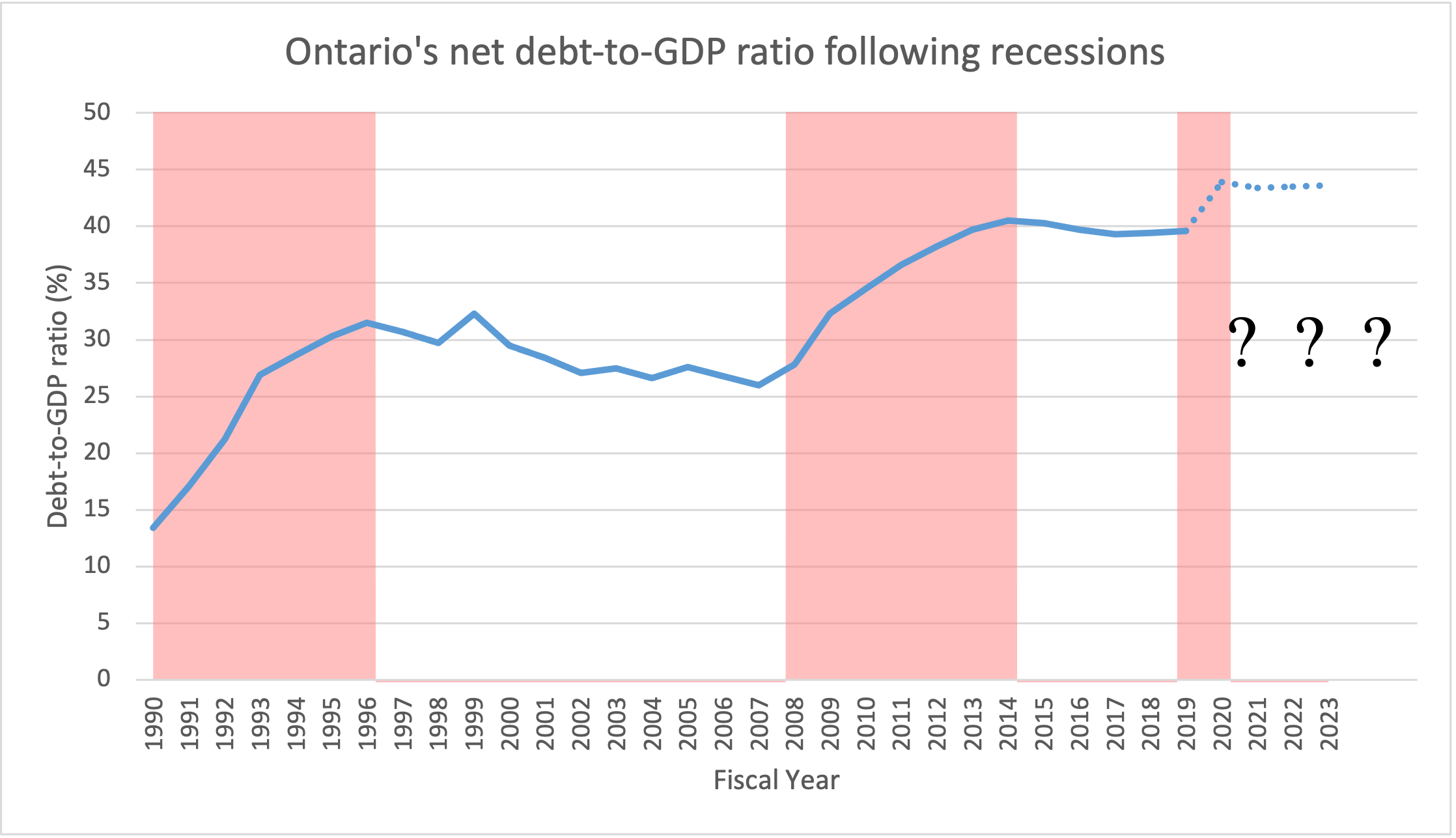

Will Ontario avoid another post-recession debt binge?

Ben Eisen, senior fellow; and Steve Lafleur, senior policy analyst, Fraser Institute

When it comes to public finances, Ontario finds itself at a crucial juncture. In the recent past, Ontario’s recessions have been followed by extended periods of debt growth. Given that the province’s finances are already unsustainable, the big question is whether history will repeat itself.

The story of Ontario’s debt accumulation pre-pandemic is a tale of two recessions. In 1991, Ontario’s debt-to-GDP ratio stood at 13.4 per cent. In the following years, the province endured a severe recession. Provincial debt climbed quickly both during the recession and in the years that immediately followed.

The 2008 recession marked another era of rapid debt-to-GDP growth during the recession and over the following half decade. This indicator proved a one-way ratchet, and held steady in the following years rather than dropping back down to pre-recession levels.

It remains to be seen whether Ontario will experience another big run-up in debt following the COVID-19 recession. The Ford government is optimistic, forecasting no further debt-to-GDP growth in the years ahead.

Given Ontario’s unsustainable debt load, budget watchers will be paying close attention to whether these optimistic forecasts come to pass, or whether Ontario will once again see its debt burden climb as it did in the 1990s and 2010s.

Stalling on Main Street

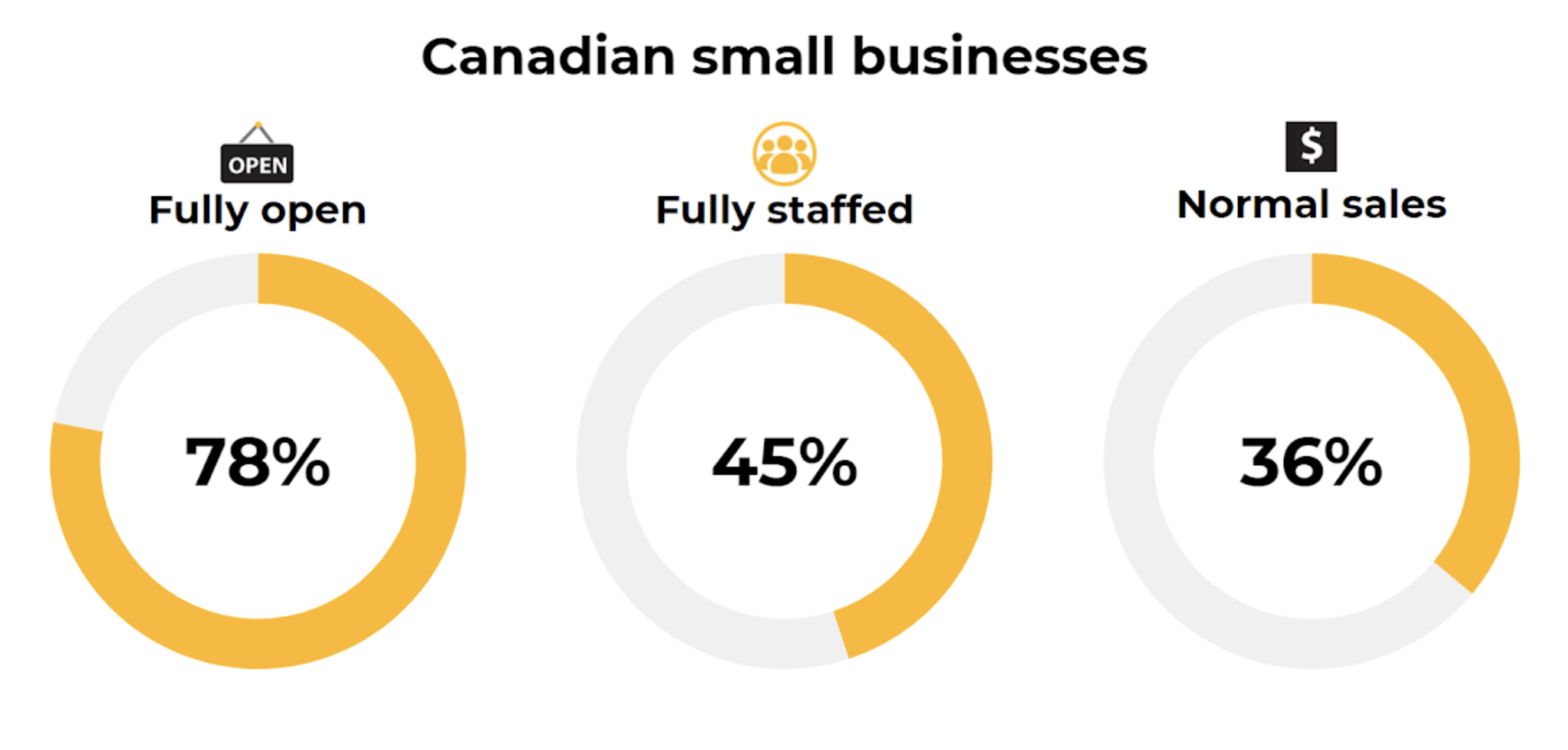

Simon Gaudreault, vice-president of national research, Canadian Federation of Independent Businesses

Source: Canadian Federation of Independent Business, smallbusinesseveryday.ca/dashboard/

Note: data above is from the November 23, 2021 update, see online dashboard for most recent version.

Two-thirds of Canada’s private sector active enterprises are microbusinesses (businesses with fewer than five employees) and one in three working Canadians owns or works in a small business (businesses with fewer than 20 employees). So, to know where our economic recovery is headed, it’s important to look at how our independent, local businesses are doing.

CFIB’s Small Business Recovery Dashboard has been doing just that in the past couple of years, tracking recovery on a regular basis by asking businesses if they consider they are fully open, fully staffed or making normal sales, compared to a pre-pandemic year. At this moment, only about three quarters are fully open, about one half have normal staffing and about one third are making regular revenues. Unfortunately, these shares have been relatively stable for the past several months, so the recovery on Main Street is now both far from completed, and is stalled.

There is still a long way to go before we can call this a full economic recovery. In the months ahead, many businesses will continue to require all the support they can get from customers and the government.

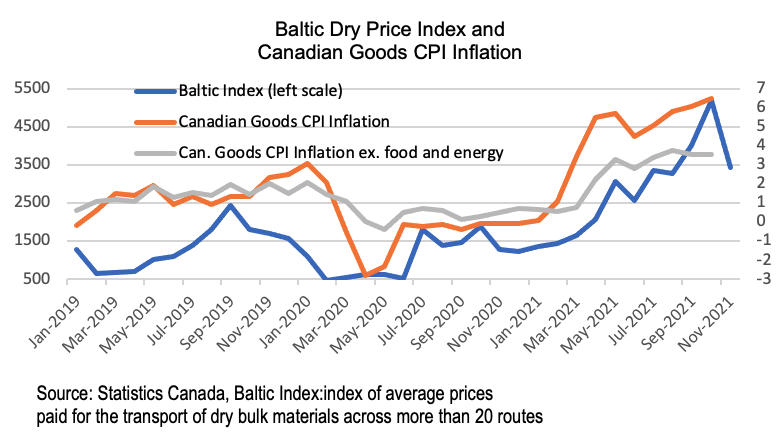

Watch the Baltic tides

Sebastien Lavoie, chief economist, Laurentian Bank

Corporate profit squeeze, erosion in purchasing power for the holiday shopping season, and easy tax grabs for governments were a big part of 2021. Many central bankers wrote “inflation cooling” on their Christmas list, but the Grinch may ruin their wish in 2022. We cannot pick one single indicator to watch in 2022 as the two-decade-high Canadian consumer price index rate comes from several forces. The global Baltic dry shipping index started to fall with logistic improvements, supportive of a slow rate of increase in the price of goods in early 2022. The supply response in commodities including oil, lumber and copper is also encouraging. Unfortunately, it is easier for retailers to change prices when input costs are soaring than declining.

This deliberate asymmetric price-fixing may slow the return of inflation closer to the two per cent Bank of Canada target. In addition, geopolitical leaders, sometimes more naughty than nice, could drive idiosyncratic price spikes. Also unpredictable are climate shocks increasing the cost of doing business, as experienced with cotton, lumber and agricultural products in 2021. Otherwise, Santa’s bag of electronics gifts gets bigger every year. This structural uptrend for microprocessor demand suggests no end in sight for the current shortage. The decarbonization transition also comes with an expensive price tag. Productivity gains and new habits including substitution favoring cheaper items could help. On the services side of CPI, the speed and magnitude of withdrawal of excess savings will be key. Economists wish you lower inflation for the New Year.

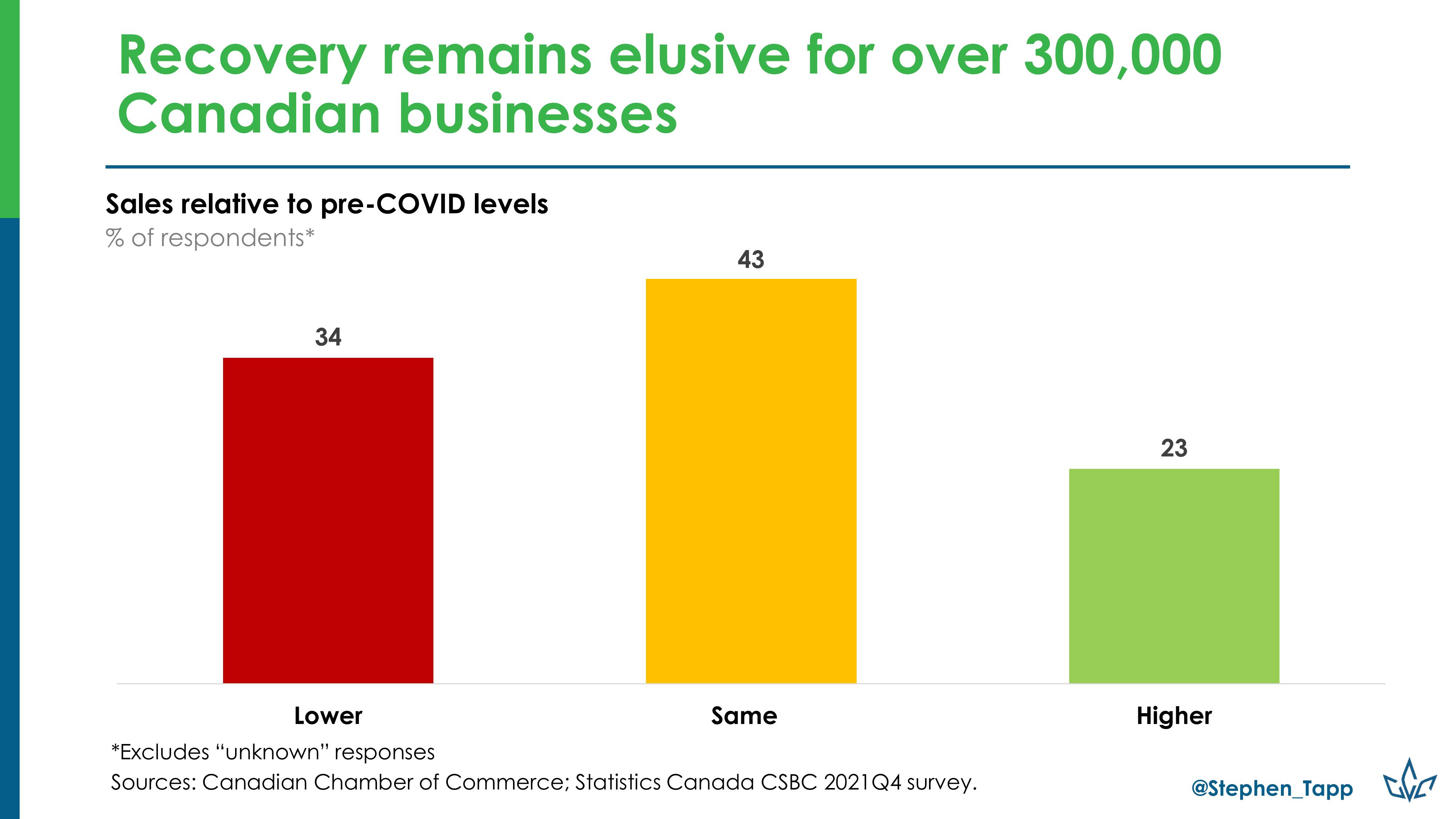

For many businesses, the comeback hasn’t come

Stephen Tapp, chief economist, Canadian Chamber of Commerce

Canada’s economic recovery gained momentum in 2021, but it remains incomplete and highly unequal. While high-tech online activity has made huge gains during the pandemic, bricks-and-mortar small businesses have been hit hard—particularly those in high-contact services. That’s why a key indicator I’ll be monitoring in 2022 is the number of Canadian companies whose sales remain below pre-pandemic levels. Statistics Canada’s latest Canadian Survey on Business Conditions puts this number at around 307,000, and finds that for 137,000 of these struggling companies (that’s 13 per cent of businesses) a full sales recovery is either “unlikely” or has an “unknown” timeline.

My chart shows that many companies (one in three) still have depressed sales. The share jumps to almost 60 per cent in the heavily disrupted sectors of accommodation and food services; and arts, entertainment and recreation. Small businesses and those owned by visible minorities are also disproportionately impacted. Many of these companies report an inability to take on more debt, and foresee challenges in repaying government supports. In the near term, profit margins are expected to shrink due to a combination of rising input costs, labour shortages and supply chain disruptions. This leaves better sales as the key lifeline. So looking to 2022, as monetary policy and government supports for businesses pull back, sales must pick up for these companies for the recovery to truly be broadly shared. Having come this far through the pandemic storm, we can’t let thousands of businesses drown 50 feet from shore.

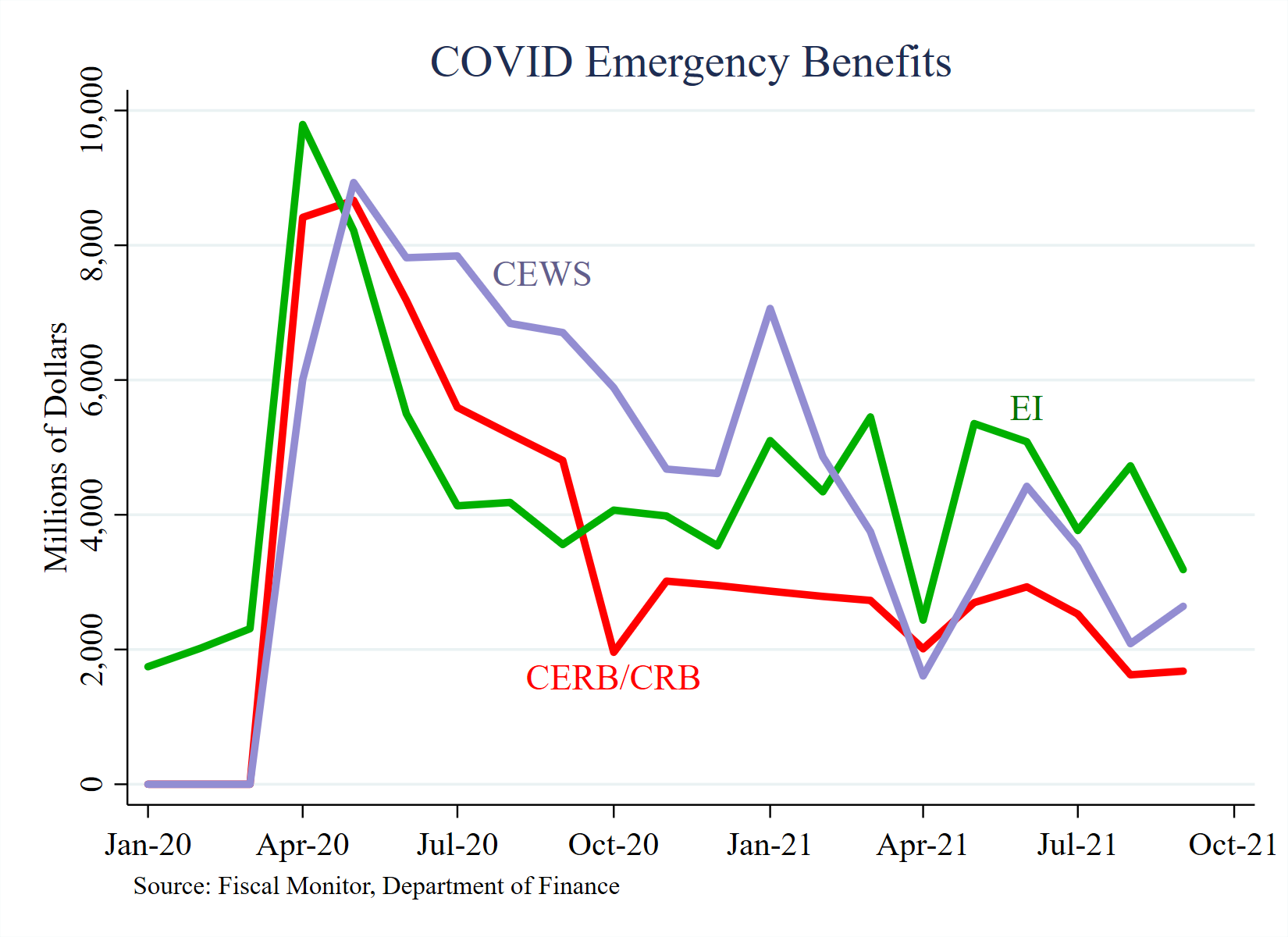

And $248 billion later…

Kevin Milligan, professor, Vancouver School of Economics, University of British Columbia @kevinmilligan

From April 2020 to September 2021, the Government of Canada spent $248 billion on the Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy (CEWS), the Canada Emergency Response Benefit/Recovery Benefit (CERB/CRB), and Employment Insurance (EI). The emergency benefits ended on October 23 of this year, but the impact of Canada’s massive emergency fiscal response will continue to shape our economy for years to come.

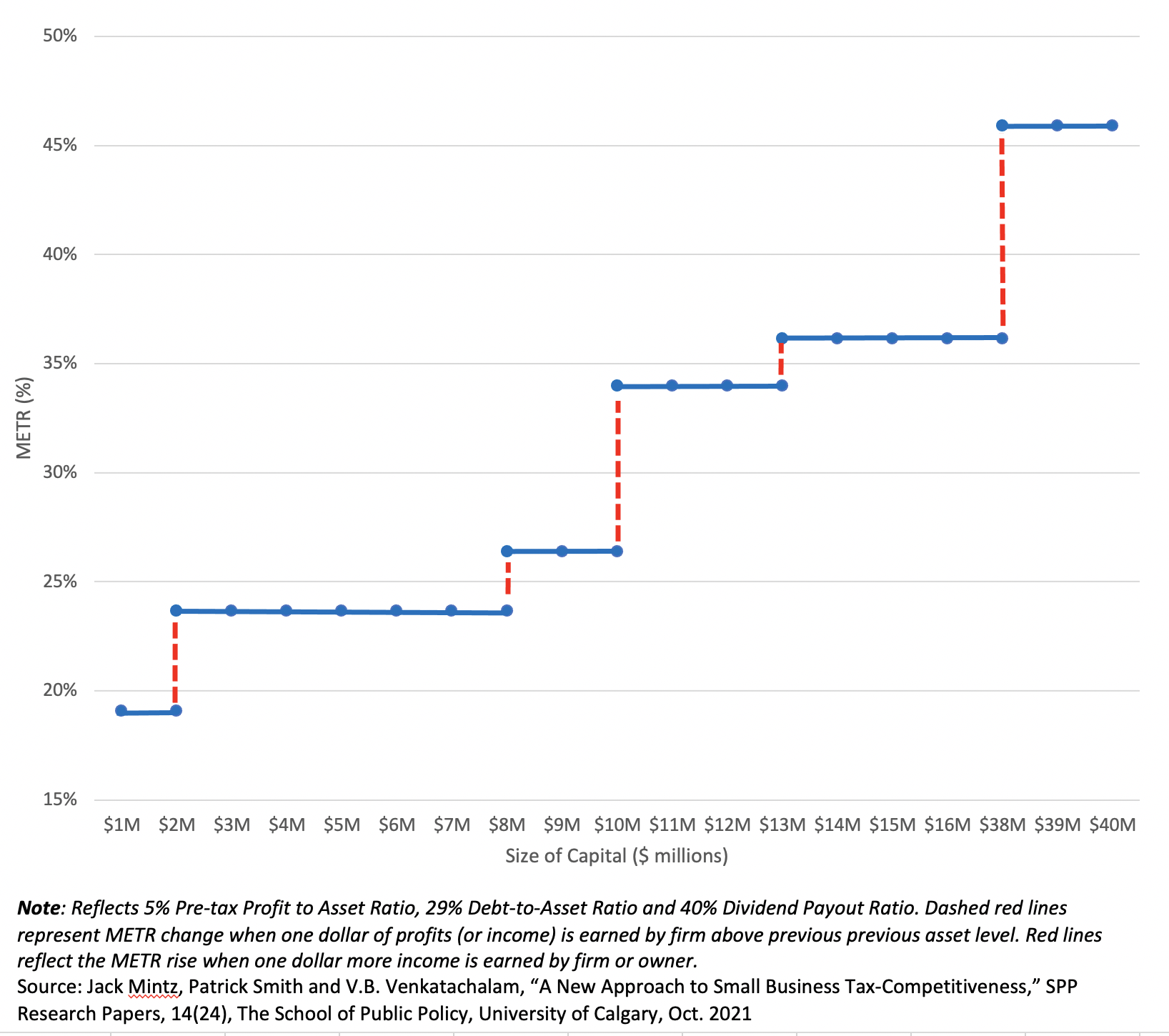

Scaling the tax wall

Jack Mintz, president’s fellow, School of Public Policy, University of Calgary @jackmintz

Analysts often focus on the corporate tax impacting small businesses, but personal taxes are even more important. This figure shows the tax wall faced by a growing small business in Canada. For a capital investment of $1 million, the effective tax rate on marginal investment (METR) for the small-business owner is 19.1 per cent. As the business grows, the METR rises as the income from the business is taxed at a higher personal progressive rate. At $3 million in assets, the METR jumps to over 23.7 per cent, due to a higher personal income tax rate. It then jumps to close to 26.4 per cent at $9 million in assets and takes a further jump to 34 per cent when assets pass the small business deduction threshold at $11 million. The highest METR is 45.9 per cent when the firm reaches $39 million in assets (and the owner is in the top personal tax bracket).

The tax wall is of interest for three reasons:

- Distortions: The tax wall provides an indication of economic distortions. When small firms are taxed at low effective tax rates compared to larger firms, the tax system encourages companies to break up to reduce their tax burden. This can be a loss in productivity.

- Growth: Companies that become larger lose tax benefits aimed at small firms—a steeper wall suggests that the tax penalty on growth is greater.

- Tax competitiveness: Canada has the steepest tax wall of all G7 countries due to rising personal and corporate tax rates. The tax wall provides information on tax competitiveness for small businesses at different investment levels. A recent study suggests that migration is particularly sensitive to personal income, payroll and consumption taxes, especially for high-income individuals, inventors and sports and entertainment professionals. The authors also found that a one-point increase in the top personal tax rate results in a percentage loss of 1.6 immigrants, based on an analysis of a Danish tax scheme providing partial tax exemptions for immigrants with incomes above a certain threshold.

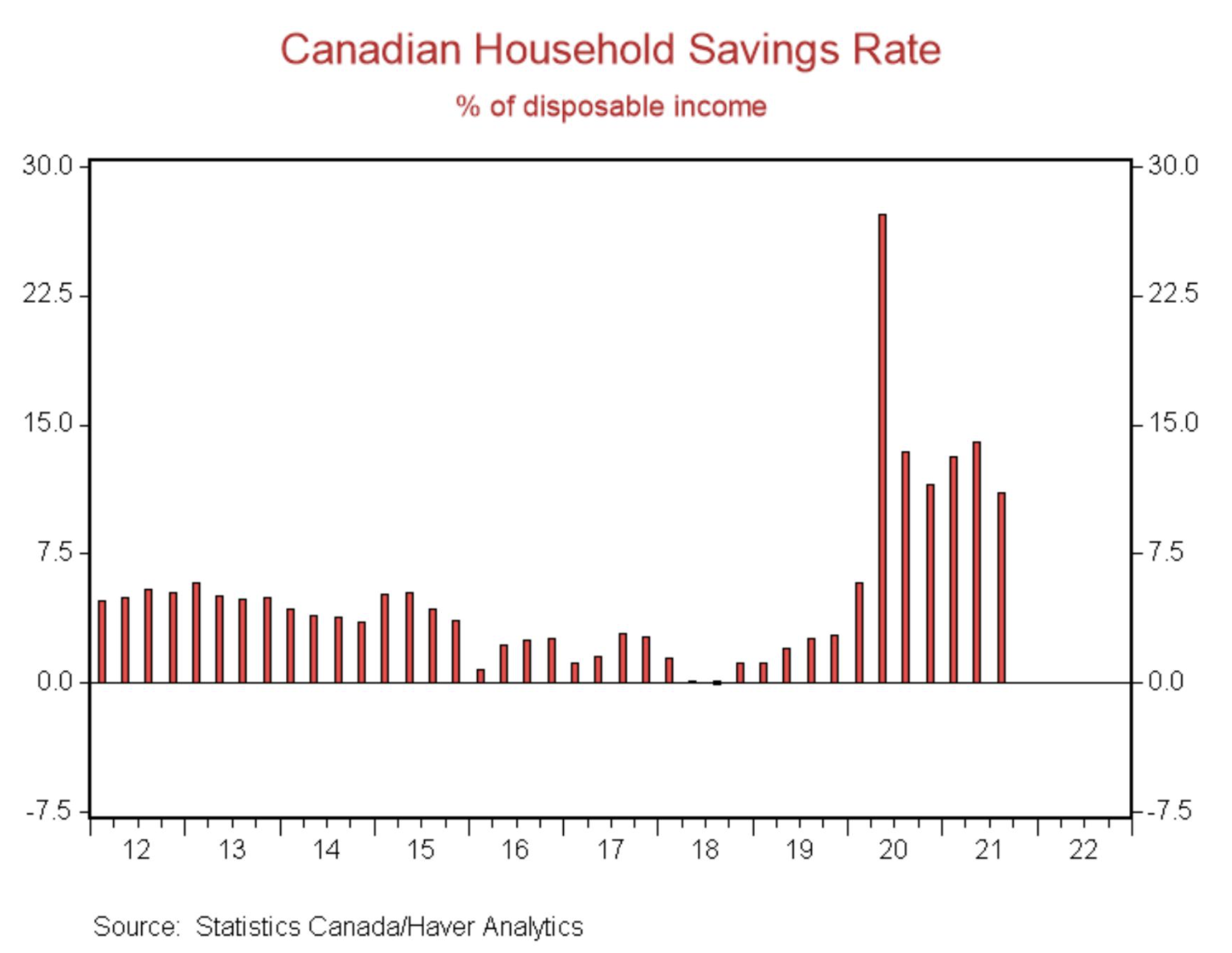

The piggy banks of a nation

Sal Guatieri, senior economist, BMO Capital Markets

Despite a near 18 per cent annualized surge in spending in the third quarter, Canadian households still managed to save a tonne of money by pre-pandemic standards. At 11 per cent, the savings rate is more than three times higher than the two-decade median. Total excess savings, over and above the 2019 rate, of nearly $300 billion during the pandemic are equivalent to 20 per cent of disposable income. That’s enough to fuel several years of consumer spending gains, though a good chunk will also be used for investments and debt repayment.

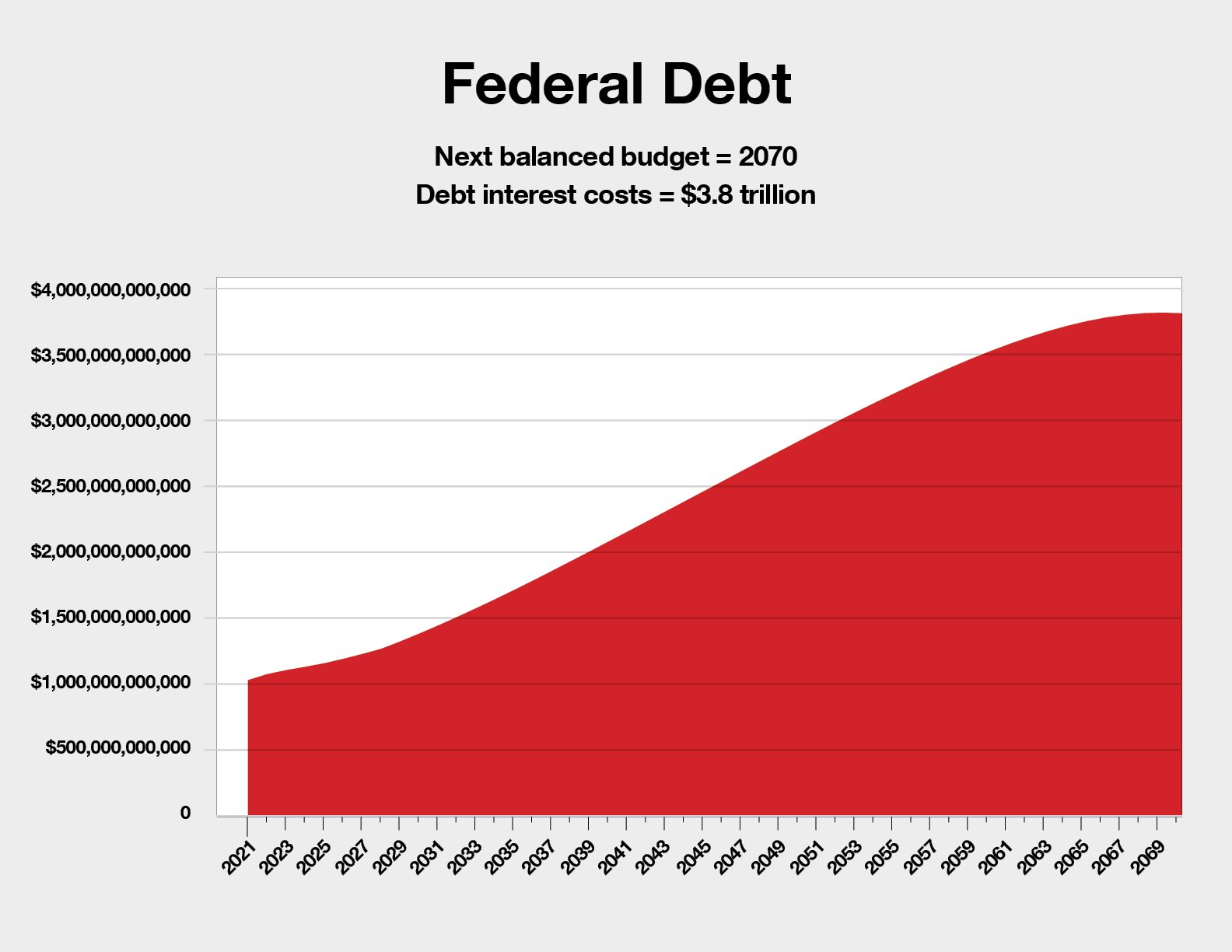

The red-ink tsunami

Franco Terrazano, federal director, Canadian Taxpayers Federation

Based on the 2021-22 federal budget, the Parliamentary Budget Officer’s data projects that the federal government will run deficits until 2070. If these five decades of deficits come to fruition, the federal government will have added another $2.7 trillion to its debt tab. That’s in addition to the current $1-trillion debt. Right now, each Canadian’s share of the federal debt is about $30,000. Under this scenario, federal debt per person will reach $67,000 in 2070. The federal government will incur about $3.8 trillion in debt interest charges over those five decades, which is money that can’t go to health care or lower taxes. The projections assume the effective interest rate will eventually settle in at 2.84 per cent, which would be lower than it was at any time between 1991 and 2014.

Once the feds finally do balance the budget in 2070, it will take at least another two decades to pay off the debt, according to the PBO’s data. Of course, these are only projections. There is nothing technically stopping the federal government from balancing the budget long before 2070. However, the Liberal Party, Conservative Party and New Democratic Party just spent the last election promising to spend $78 billion, $51 billion and $214 billion, respectively—more than in budget 2021-22.