13 charts to watch on health, families and population in 2022

Chart Week 2022: Global vaccine trends, quantifying how the jabs saved lives, the next child care crunch, and more

Share

For Maclean’s eighth annual chartstravaganza, we’ve once again asked dozens of economists and analysts to ponder the year to come, choose one chart that will help define Canada’s economy in 2022 and beyond, and explain this outlook in their own words.

This year, we’ve decided to release the charts over several days before Christmas, making this more of a Chart Week than a one-day data binge. We’ll cover jobs and income, inflation, energy and—yes, don’t worry—real-estate outlooks.

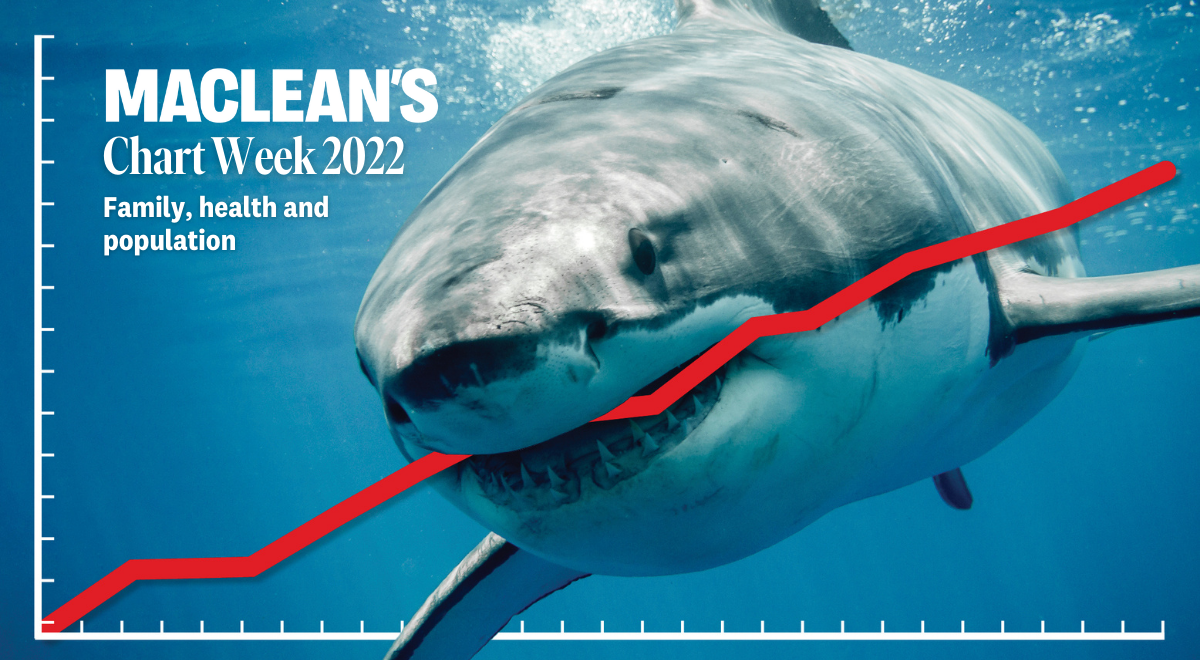

The global vaccine gap

Danielle Goldfarb, head of global research, RIWI

The COVID-19 pandemic and most recently the emergence of the Omicron variant have made it clear that (a) Canada is deeply integrated into the global economy, and (b) it is not possible to keep COVID out by shutting down borders. So I think the most important chart for Canadians to watch in 2022 is the trend in global vaccinations.

Until a much much greater share of the global population is vaccinated, and until vaccine supply increases in low-income countries, we will continue to see a higher rate of supply chain disruptions (and higher inflation), travel restrictions, and uncertainty around lockdowns and school shutdowns both in Canada and around the world. Getting a higher share of the global population vaccinated is no guarantee that these problems will go away. But a speedier rate of global vaccination, particularly in lower-income countries, will increase the odds of a more stable and certain trajectory for Canada’s economy in 2022.

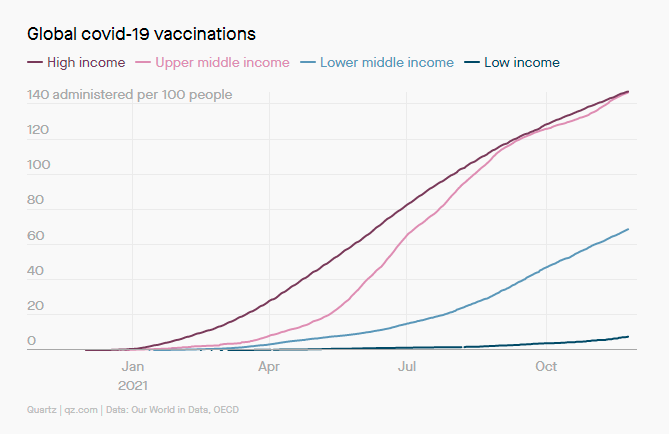

The global vaccine abundance

Derek Holt, vice-president and head of capital markets economics, Scotiabank

Could 2022 be the year that ends the pandemic and turns the COVID-19 virus into something much less threatening? Omicron counsels nearer-term caution, but science could still make it so. Despite damaged global supply chains, the world is on track to produce enough vaccine to fully vaccinate 5.8 billion people in 2021. In addition to how behaviour and public health measures have adapted, antibody treatments appear to be promising. These tools will complement a further massive surge in vaccine production in 2022. Even absent a running head start, current production plans for 2022 point toward having enough vaccine to fully vaccinate the entire world population plus give one booster shot to everyone—and still have surplus. If new vaccines are required to counter new variants, then the capacity exists to pivot as needed which is a big shift from the capacity shortages of a year ago. A new set of opportunities and challenges lies ahead for economies and markets.

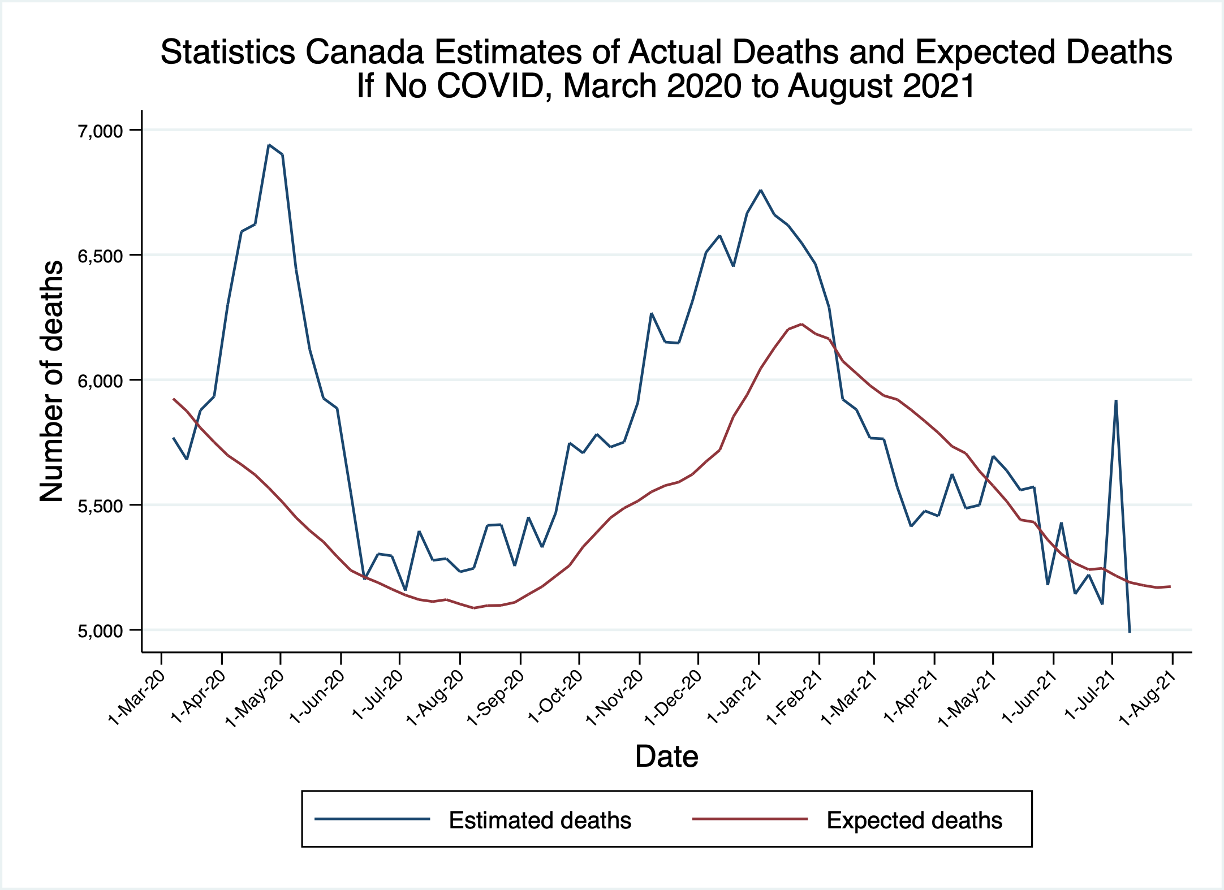

Vaccines are saving lives, quantified

Alyssa Drost, PhD candidate; and Mike Veall, professor, Department of Economics, McMaster University

Without COVID, it would be expected that five to six thousand Canadians would die per week. This is the “expected deaths” red line, drawn from Statistics Canada projections based on pre-pandemic experience. The blue line on the chart is the Statistics Canada estimate of actual deaths. From pandemic onset to January 2021, the blue line was above the red line as COVID took its toll. But the advent of vaccines brought the death rate down to the expected rate levels very quickly and now, save one unusual week in July, death rates are what they would be expected to be if there were no COVID.

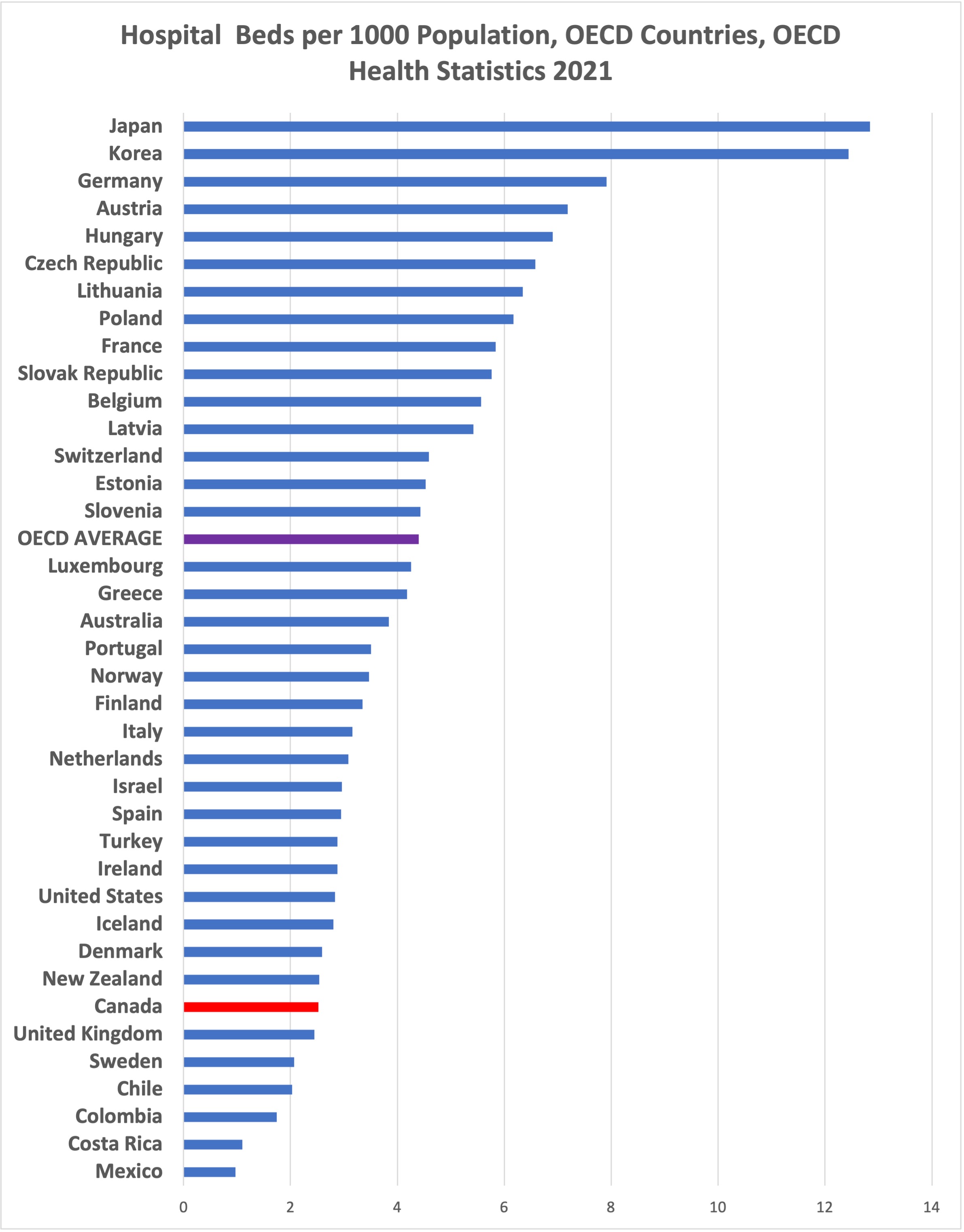

Pandemics and hospital beds

Livio Di Matteo, professor, Department of Economics, Lakehead University

The impact of COVID-19 on health spending in Canada has been immense.

According to the Canadian Institute for Health Information, Canada is expected to spend a new record of $308 billion on health care in 2021 — $8,019 per Canadian. It is also anticipated that health expenditure will represent 12.7 per cent of Canada’s gross domestic product in 2021, following a high of 13.7 per cent in 2020 – both up from 11.5 percent in 2019. Notwithstanding the impact on long-term care residents, Canada did relatively well during the pandemic in terms of mortality. However, the prolonged lockdowns that were implemented in many provinces were in the end necessary because despite some of the highest health spending in the world, Canada did not have as many crucial health resources compared to other developed countries and its health system was constantly in danger of being overwhelmed. According to the 2021 OECD Health Statistics, among the 38 OECD countries, Canada has the 7th highest health spending to GDP ratio and yet ranks 30th in terms of physicians per 1,000 population and 32nd in hospital beds per capita. As the accompanying figure illustrates, hospital beds per 1,000 population range from a high of 12.8 for Japan to a low of 1 in Mexico with the OECD average at 4.4. Canada comes in at 2.5 beds per 1,000. As the post-mortem of how we dealt with COVID-19 inevitably gains momentum in 2022, Canadians will be keen to understand how a health system that spends so much seems to have so many fewer beds and physicians per capita.

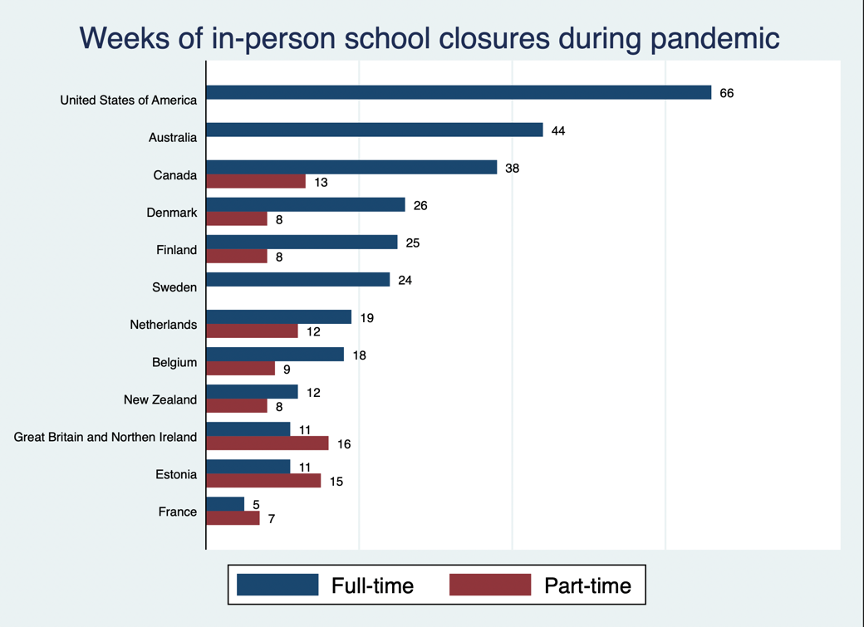

When class is dismissed for too long

Catherine Haeck, professor of economics, Université du Québec à Montréal

Note: Closures are calculated from March 14, 2020, to Oct. 31, 2021. Full-time closures imply that all schools across the country are closed to in-person learning. Part-time closures include weeks in which schools were open in certain parts of the country but not others, or in certain grades but not others, or in-person class-time was reduced and combined with distance learning.

Data source : UNESCO data on pre-primary to upper secondary school closures as of Oct. 31, 2021 accessible at : http://covid19.uis.unesco.org/global-monitoring-school-closures-covid19/.

Canadian children have made large sacrifices to keep everyone safe. Virtual schooling is not as effective with younger kids and early learning experiences are building blocks for later educational success. While teachers will alleviate some of the losses, the extent of the potential damages caused by the pandemic call for meaningful investment in K-12, especially in disadvantaged areas.

Research using administrative data from Belgium and the Netherlands show that students have indeed fallen behind following the pandemic classroom closures, and this is especially true for vulnerable students. Research also shows prolonged school closures cause long-lasting negative consequences in the absence of remediation. Since standardized tests have been postponed and Canada does not collect high-quality pan-Canadian data on K-12 children on a regular basis, we are currently unable to monitor the impact of the pandemic on kids’ academic progress across the country.

So next year we should watch out for data on children’s academic progress by socioeconomic status and government spending in K-12. New data should become available near the end of the year which will help us gain some perspective on teenagers’ academic performance relative to past performance over the last 20 years. Clearly this is not sufficient, but it is unfortunately the best our country seems to be willing to do.

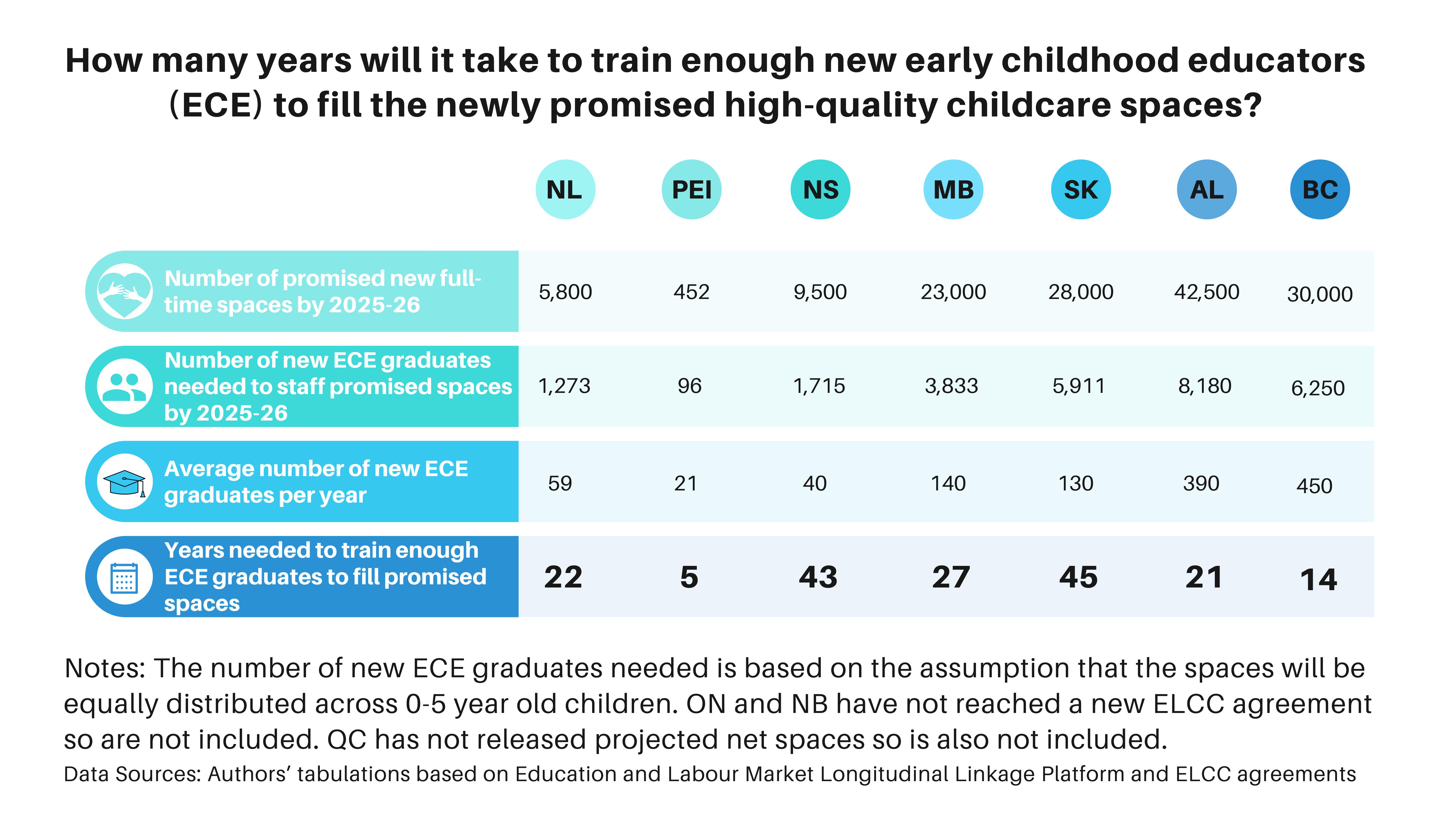

The next childcare crunch: staff

Elizabeth Dhuey, associate professor of economics, Department of Management, University of Toronto @bdhuey

The pandemic brought the importance of childcare into focus for Canada, because without access to child care, parents cannot fully participate in the labour market.

In the last budget, the federal government set a goal of offering $10-a-day childcare within a five-year time period. Most provinces have signed on to childcare agreements with the federal government that include lowering fees and increasing high-quality licensed childcare spaces. This chart illustrates the difficulty that provinces might have when trying to meet their agreements due to the lack of capacity to train new early childhood educators (ECE). Given the current capacity and demand of students for these programs, Canada will have a huge shortfall of trained ECEs to staff these new high-quality childcare spaces. Although not every staff needs an ECE degree, in order to provide high-quality care and education to our children, providing sufficient ECE graduates to the childcare workforce becomes more than essential.

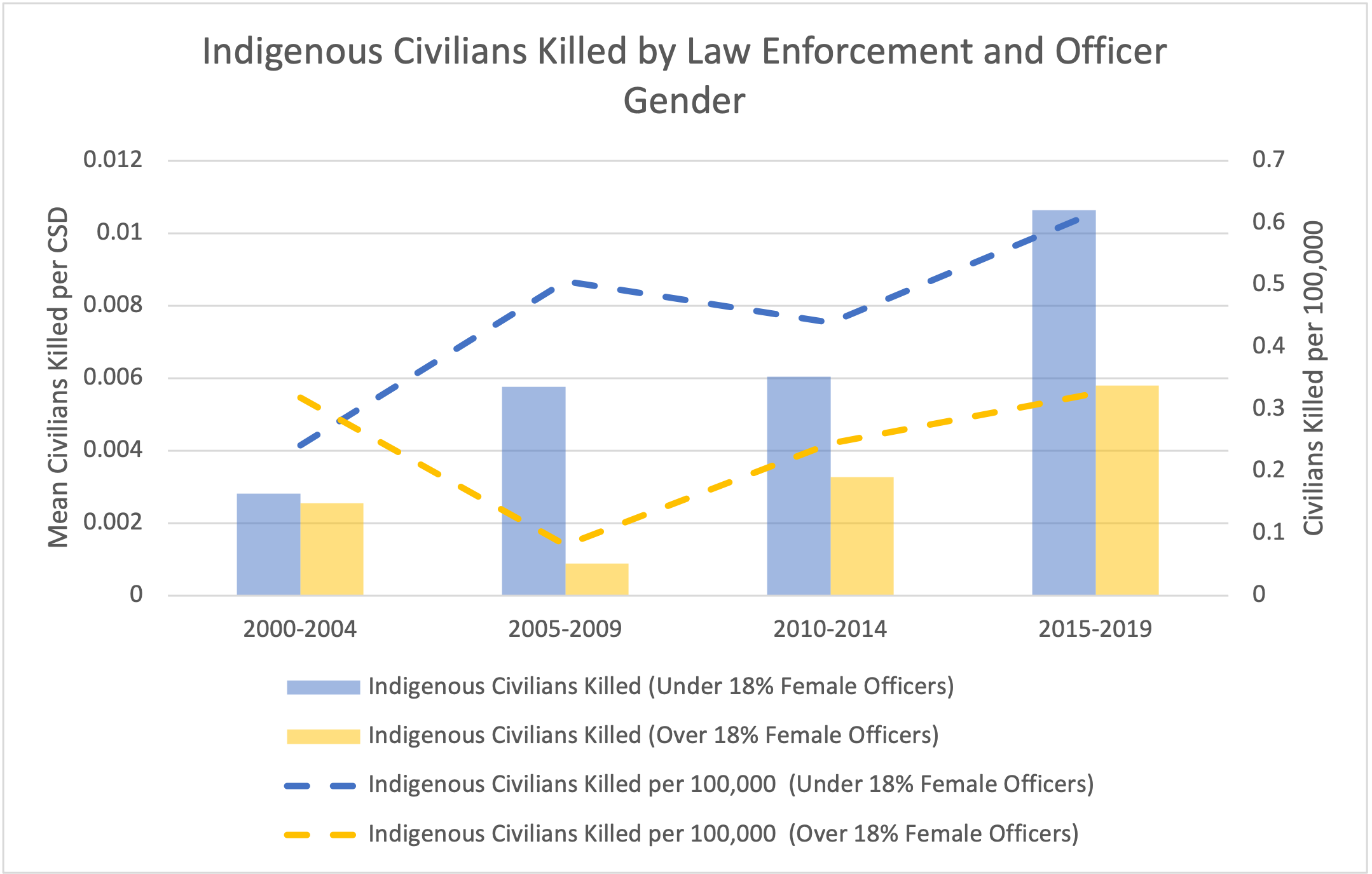

Lethal force and police diversity

Rob Gillezeau, assistant professor of economics, University of Victoria @robgillezeau

Sources: Gillezeau, Rushford, and Weaver (2021); Marcoux and Nicholson (2020), Police Administration Survey (2020), Census of Population

There has been a marked increase in law enforcement’s use of lethal force against Indigenous people and the population more broadly over the last two decades. Using information from the Police Administration Survey on gender ratios in Canadian police forces and data from CBC’s Deadly Force dataset, we can see that there has been a dramatic divergence in the use of force based on officer gender diversity. This suggests that U.S.-based findings regarding the importance of police force diversity in limiting the use of force and discrimination may hold in Canada. In the year ahead, it will be important to track if governments and police forces respond with explicit policy interventions such as increasing force diversity to limit the increase in the use of lethal force and ensure non-discrimination.

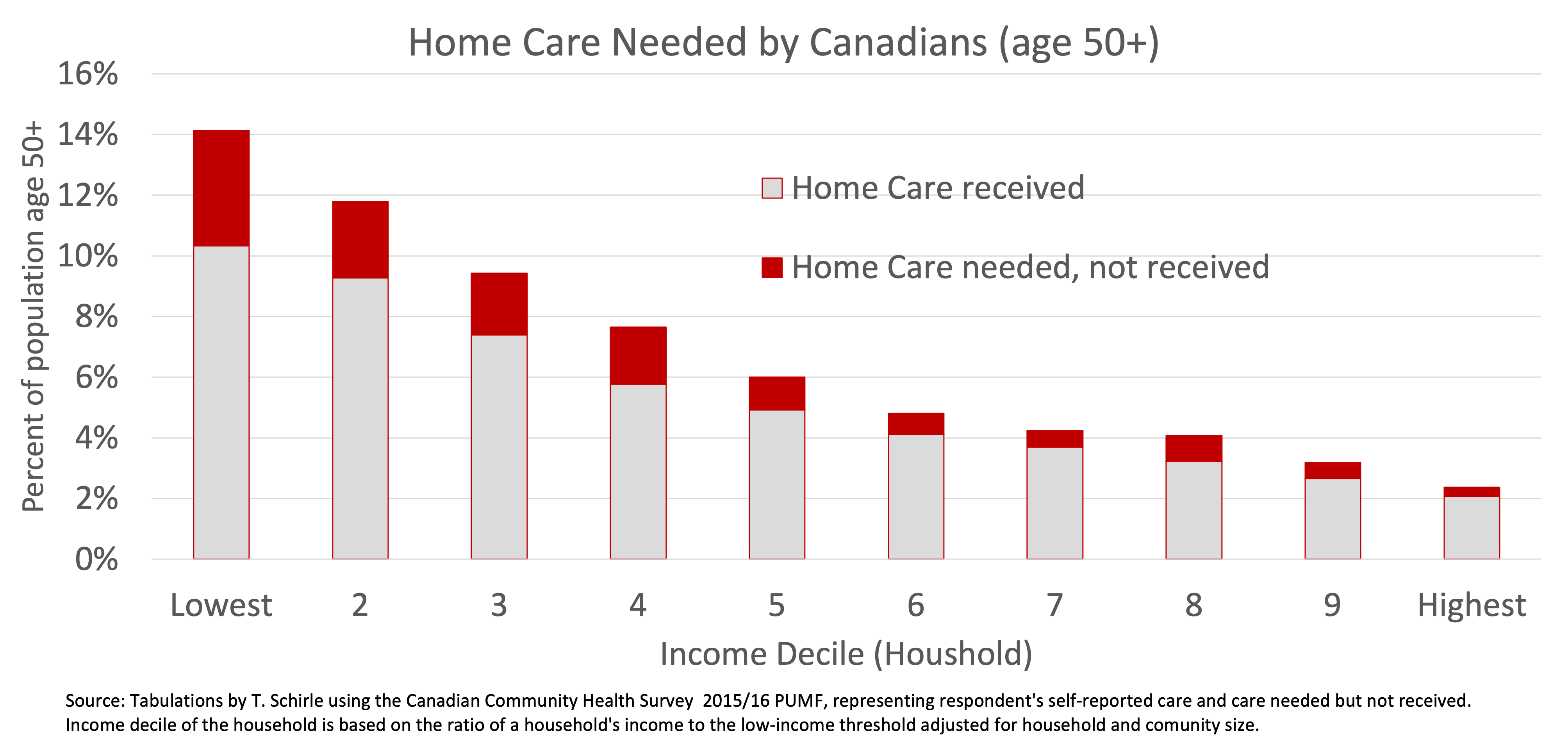

The home care have-nots

Tammy Schirle, professor of economics, Wilfrid Laurier University @tammyschirle

Over the next decade, an increasing number of Canadians will need home care services. In the past, we’ve seen that help did not arrive for many older Canadians with low income. While over 10 per cent of the lowest-income Canadians over age 50 reported receiving home care services, an additional four per cent reported needing services but not receiving them. When services are not made available, responsibility for care will often fall to family and friends—usually to daughters who will face juggling these responsibilities with work and their own kids. But are Canadians willing to spend more to support older Canadians needing care at home? In 2021, home and community care made up more than five per cent of provinces’ health spending. Looking ahead, I’m concerned the provinces—and the families therein—will struggle to meet a growing demand for care.

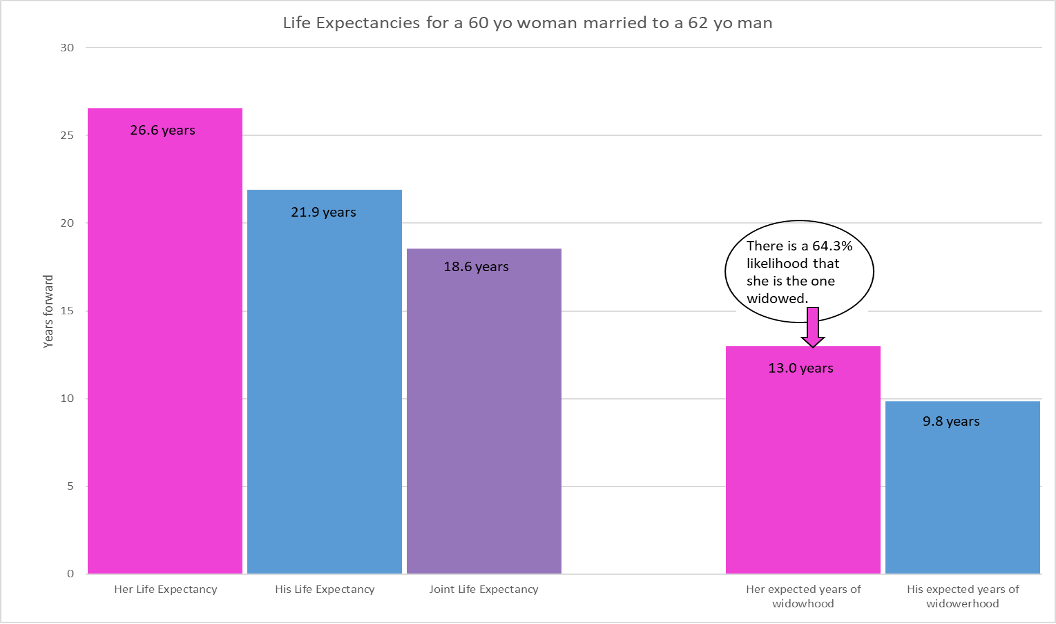

What to expect with your life expectancy

Janice Compton, associate professor, University of Manitoba

The labour force participation rate among 55- to 64-year-olds has suffered the largest decline during the pandemic, as many Canadians have moved their retirement plans forward. One of the key considerations when planning for retirement and long-term healthcare is individual life expectancy. Although age at death is uncertain, the choices made by someone who anticipates living to 100 will be very different than for someone who foresees an early death. Published life expectancy numbers are only averages, but they do provide benchmarks to which we can anchor our individual expectations.

However, many individuals facing decisions of retirement and long-term health planning are not facing the decisions solo, but rather as part of a couple. A couple should consider not only their individual life expectancies but also how many years they can expect to both be alive (joint life expectancy), and how many years of widowhood they should expect on average (survivor life expectancy). However, while retirement planning websites include life expectancy calculators for individuals, couple-based measures are not widely available. Moreover, if joint and survivor life expectancies are naively calculated from individual life expectancies, they can be quite misleading. In particular, duration of widowhood is likely to be severely underestimated.

Before considering early retirement, understand how this decision will affect your spouse if you die first, and plan for longer widowhoods (and widowerhoods) than the individual life expectancies might lead you to believe.

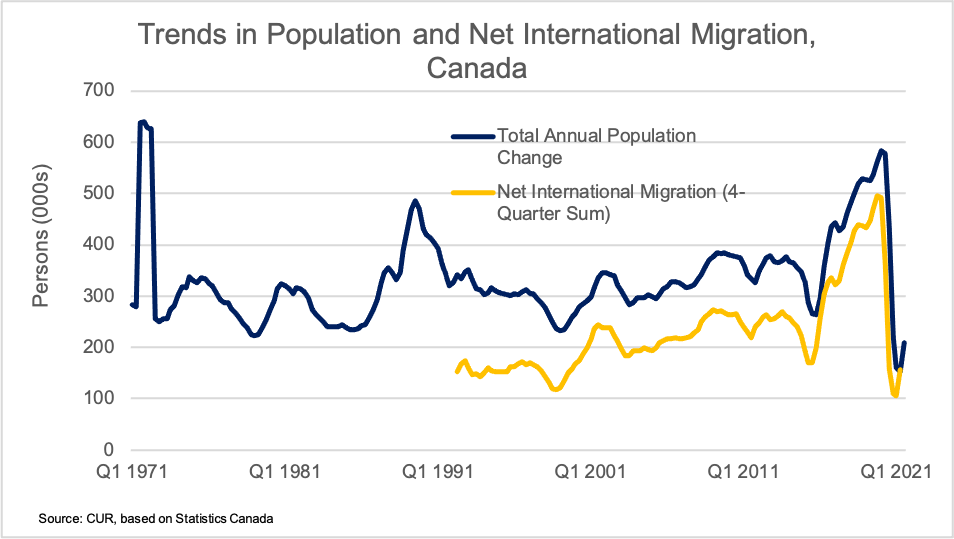

Will population growth rebound?

Diana Petramala, senior economist, Centre for Urban Research and Land Development, Ryerson University

Between early 2018 and the first half of 2020, Canada’s population was growing by the fastest rate since the early 1970s. Now it’s growing at its slowest rate in more than 50 years. Immigration plummeted along with the strictest lockdown measures during the pandemic, dragging overall population growth with it. Immigration is yet to bounce back, even with borders open. It will be interesting to see if and how fast population growth turns around in 2022 and what the possible knock-on effects will be for the housing market and overall economy.

Moncton Calling

David Chaundy, president and CEO, Atlantic Provinces Economic Council

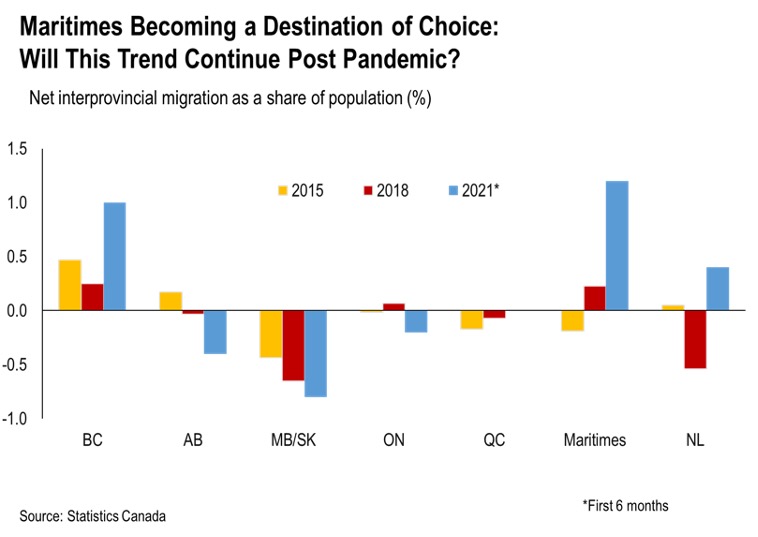

Canada’s migration patterns are changing. While COVID-19 has increased net flows to the east and west coasts, some of these shifts were already apparent.

Atlantic Canada has experienced decades of net out-migration to other parts of Canada, as young people in particular left for opportunities elsewhere. However, leading up to the pandemic, flows were shifting back into the Maritime provinces. This reversal in net interprovincial migration was coupled with an increase in immigration to the Maritimes.

During the pandemic, migration from other provinces into Atlantic Canada accelerated due to lower COVID-19 case levels and more affordable housing. Atlantic Canada attracted a net flow of 15,000 people from Ontario and 3,000 from Alberta since the start of 2020. This high level of migration over the first half of 2021 has pushed the region’s population growth above the national rate for the first time in recent memory.

Will these positive interprovincial flows into Atlantic Canada continue post-pandemic? The region’s demographics point to a need to retain and attract workers, although every province will need talent. While home values are rising, prices are still less than a quarter to a third of the Toronto level. Less congestion and remote work opportunities are likely to remain favourable for continued migration, which means the region must ensure it can provide sufficient housing, health and other public services that newcomers will need.

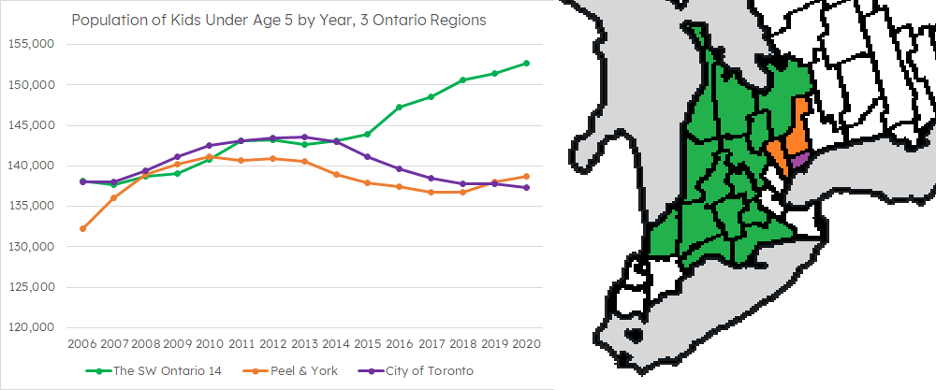

The rise of southwestern Ontario’s exurbs

Mike P. Moffatt, senior director of policy and innovation, Smart Prosperity Institute @MikePMoffatt

A shortage of attainable and available family-friendly housing options has caused an exodus of young families out of the Greater Toronto Area. These “drive until you qualify” households have spread across Southwestern Ontario, with the population of kids under five years old in 14 Ontario census divisions (Brant, Bruce, Dufferin, Elgin, Grey, Haldimand-Norfolk, Huron, Lambton, Middlesex, Oxford, Perth, Simcoe, Waterloo, and Wellington) having risen by six per cent since 2015, while falling three per cent in the City of Toronto.

While the population of preschool-age kids is increasing in larger centres like Waterloo and London, much of the growth is occurring in smaller communities. Huron-Kinloss, North Perth, Southgate, East Zorra-Tavistock, and Mono have among the fastest growing population of young kids in the country.

Families moving out of Toronto to the suburbs is nothing new, but what we’ve seen in the past few years is a move to the “exurbs,” more remote locations which are a considerable distance away and not accessible by transit. This trend, which started in 2015, has almost certainly accelerated during the pandemic, with the rise of “work from home.” This has implications on everything from Canada’s ability to hit climate targets (as carbon footprints per capita are higher in smaller communities) to the province’s infrastructure needs. And we should not ignore how this could affect Ontario’s politics, as soccer fields are being installed where Tillsonburg’s famous tobacco fields once were.

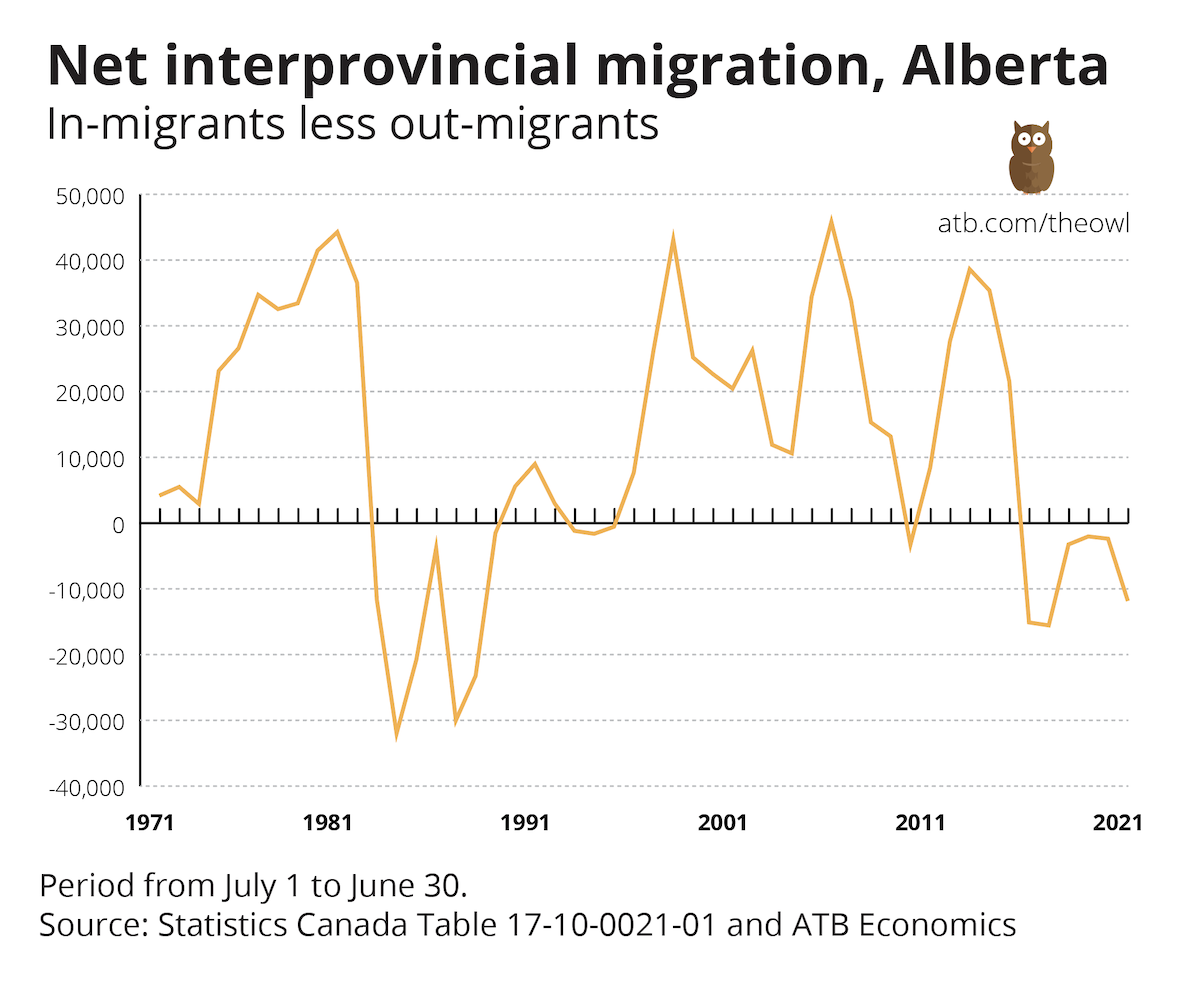

Finding work in Alberta

Robert Roach, deputy chief economist, ATB Financial @roachomics

Interprovincial migration takes place for a wide range of reasons, but the promise of a good job is often a key factor and Alberta’s strong record of high-wage job creation has helped make it the second-most popular destination for Canadians on both an absolute and net basis. At almost 3.8 million, Ontario has seen the most people move in from other parts of Canada since 1971, but Alberta is not far behind at 3.4 million. When we account for people leaving for other provinces or territories, British Columbia tops the list with a net gain since 1971 of almost 700,000 residents, followed by Alberta at about 591,000. The next closest province is Ontario, which is ahead by just 9,257.

Interprovincial migration works like a safety valve that enables people looking for work to flow to where the jobs are. As such, Alberta and B.C. have played a particularly important role in keeping unemployment down in other parts of Canada.

Here’s the rub: While Alberta remains a great place to live and work, its ability to generate lots of “extra” jobs has been hamstrung since the oil price crash that brought on the provincial recession of 2015-16. It’s no coincidence that Alberta has seen a net outflow of about 50,000 people since that time. Those inclined toward schadenfreude might think this is just Alberta’s problem, when, in fact, it hurts job seekers across the country. This is why it’s important to watch the interprovincial numbers in 2022 to see if Alberta can return to its traditional role as one of Canada’s job creation hot spots.