18 charts that define how we’ll work and make money in 2022

Chart Week 2022: The situation gets worse for the self-employed, fewer older women have jobs, the gender divide in WFH happiness, and more

Share

After a 2020 that brought the greatest shocks in generations to our economy and society, 2021 did offer some recovery and bounce-back, along with several new or distressingly familiar jolts, like the highest inflation since millennials were in carseats. More of us are working, but work doesn’t always look the same—or it still involves a laptop on the kitchen table. And with the Omicron variant rearing its terrifying, spiky head, visions of hope for a decidedly better 2022 have gotten much hazier.

For Maclean’s eighth annual chartstravaganza, we’ve once again asked dozens of economists and analysts to ponder the year to come, choose one chart that will help define Canada’s economy in 2022 and beyond, and explain this outlook in their own words.

This year, we’ve decided to release the charts over several days before Christmas, making this more of a Chart Week than a one-day data binge. Today, we release the charts on jobs and income. Coming up are those on inflation, COVID, energy and—yes, don’t worry—real-estate outlooks.

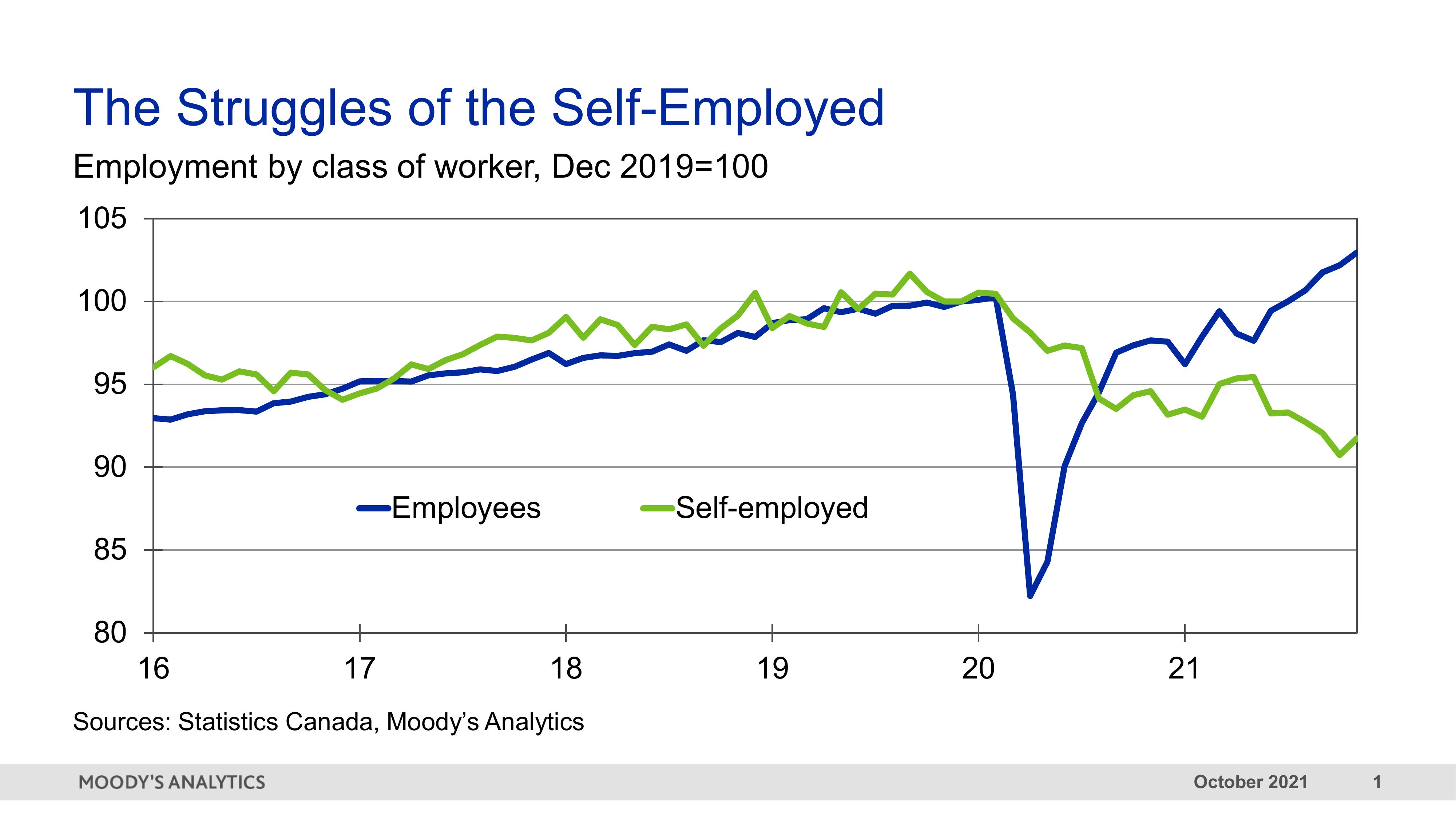

The self-employment blues

Brendan LaCerda, senior economist, Moody’s Analytics

Initially, for the 16 per cent of Canadian workers who are self-employed, the worst of the crisis seemed to be avoided. However, while the rest of the labour market rapidly rebounded, the situation for the self-employed has continued to deteriorate. The breakdown by gender shows that males drove the initial decline, but their number has trended slightly higher since late 2020.

In contrast, female self-employment has seen no recovery and continues to fall, marking a stunning reversal after years of progress in increasing the number of female entrepreneurs. In 2022, we will be keeping a close eye on these small businesses to see if their fortunes reverse. Entrepreneurship drives innovation and productivity growth. Its absence could entail serious long-term harm.

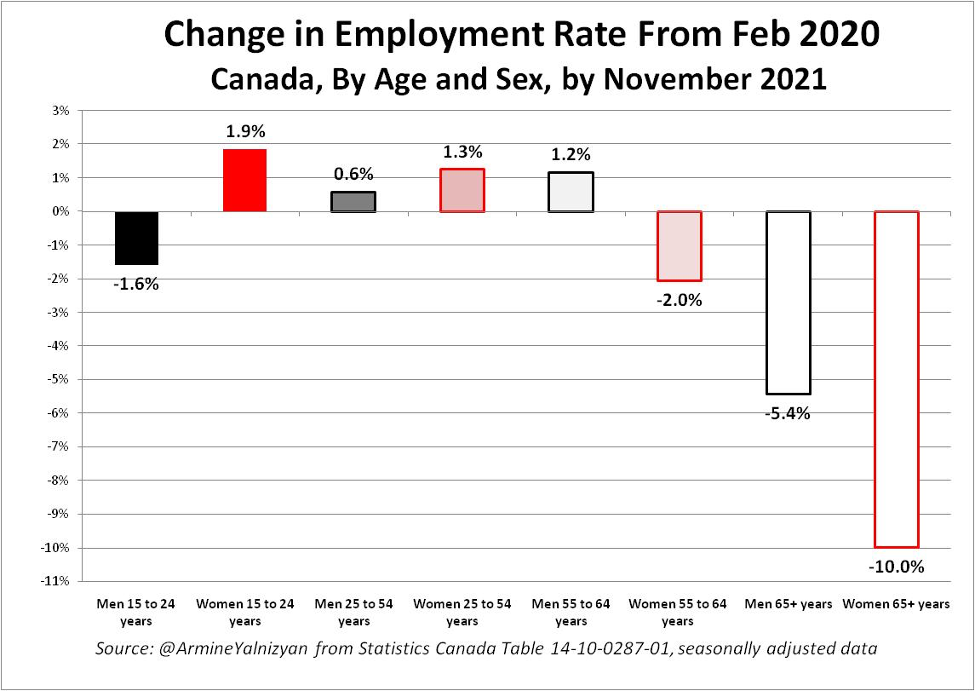

After she-cession, the intergenerational challenges of she-covery

Armine Yalinzyan, Atkinson Fellow on the Future of Workers

Historically recessions have meant more men than women initially lose (usually better-paid) work in an economic downturn and more women find (lower-paid) jobs first in the initial stages of recovery. Hence he-cessions are typically followed by she-coveries. This time everything’s reversed: more women lost jobs initially, and more men got back to work first. The pandemic has also turned the usual intergenerational patterns of recovery upside down.

Normally young people get hit hardest, and come back last. That was true for the job losses, but young women have been leading the parade of the share of the population that has paid work since the summer, while fewer older women have a job than pre-pandemic. This is another inversion of past patterns when older women were the reserve army of labour, most willing to work at part time jobs for low pay when the primary earner got knocked out of the job market. We don’t know why tens of thousands fewer women aged 55 and older are not employed now, while tens of thousands more men aged 55 and older are. There are at least three likely causes: 1) more burn out, as more women work in healthcare, eldercare and childcare; 2) more businesses that employed older women which have shuttered or haven’t resumed regular business levels; or 3) more older women have stepped out of the paid job market to support their adult children who might otherwise have trouble keeping their jobs, given the challenges of schools and childcare facilities closing down. Existing data don’t permit understanding of what mix of factors may be at play, so it’s hard to tell if this is a new normal, or if she-covery will someday extend to all women who want and need to work.

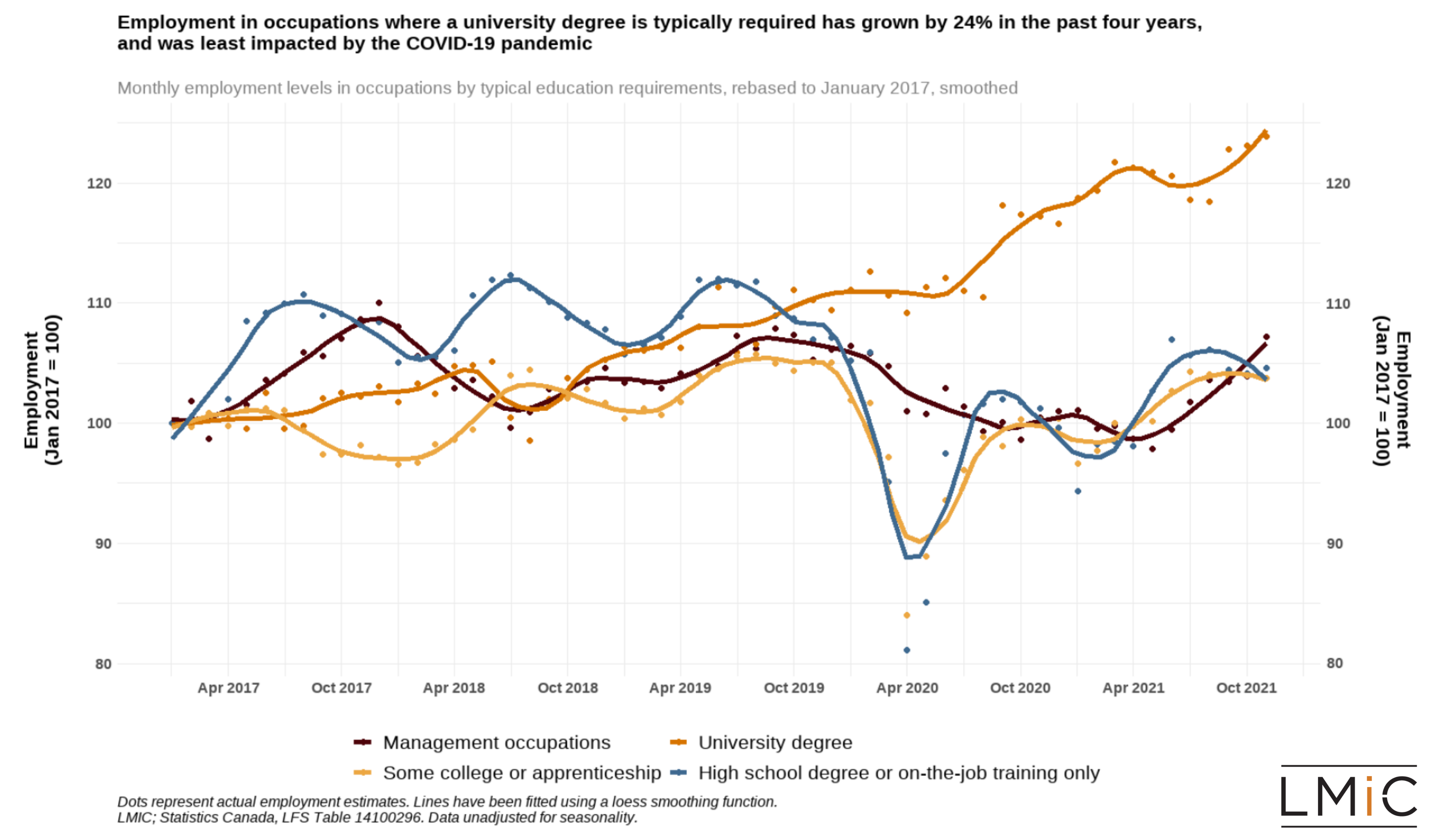

Larger by degrees

Bolanle Alake-Apata, economist, Labour Market Information Council

Job losses due to the pandemic have been concentrated among non-management occupations and those that typically require college degrees or less. This figure shows the employment level relative to January 2017 through November 2021. Not only has employment increased significantly in occupations where university degrees are required, pandemic-related job loss in these occupations was comparatively much lower.

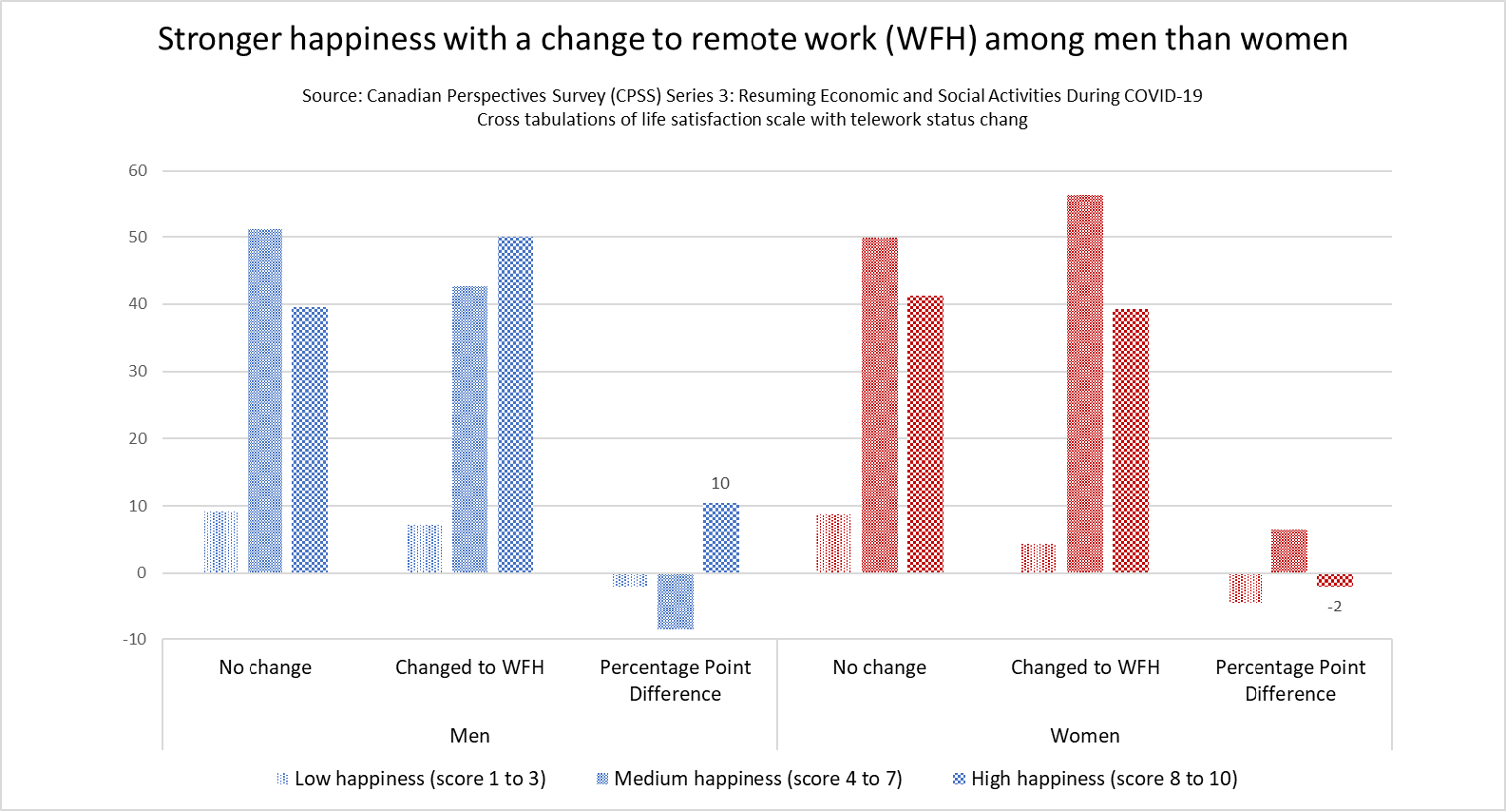

Who’s happy at the home office

Stéphanie Lluis, associate professor, Department of Economics, University of Waterloo

The pandemic revealed that many jobs can be performed from home instead of at an employer’s work location. This may be great news for businesses.

In June 2021, a working from home survey from the Business Development Bank of Canada (BDC) found that 74 per cent of businesses plan to offer employees remote work after the pandemic and 55 per cent of employees want to work remotely as much or more than they do now.

However, there seems to be a gender divide according to the CPSS survey data collected in June 2020, following the initial lifting of public health restrictions. Men are much happier with the change of work location than women.

Relative to workers who experienced no change in work location (continuing to work either outside or at home), a greater proportion of men who changed their work location (from outside to at home) show larger levels of life satisfaction.

Working remotely could be experienced by men as providing a welcome and desirable increase in job flexibility (keeping in mind that in most managerial and professional occupations, more than 20 per cent of men still work more than 50 hours per week). For women, however, working from home could mean distancing from and missing out on career advancement opportunities more easily generated by in-person interactions, especially in highly competitive professional and managerial occupations.

To watch in 2022: is remote work going to revert back to pre-pandemic levels and, if not, will increased remote work opportunities hinder or reduce gender inequality in the workplace?

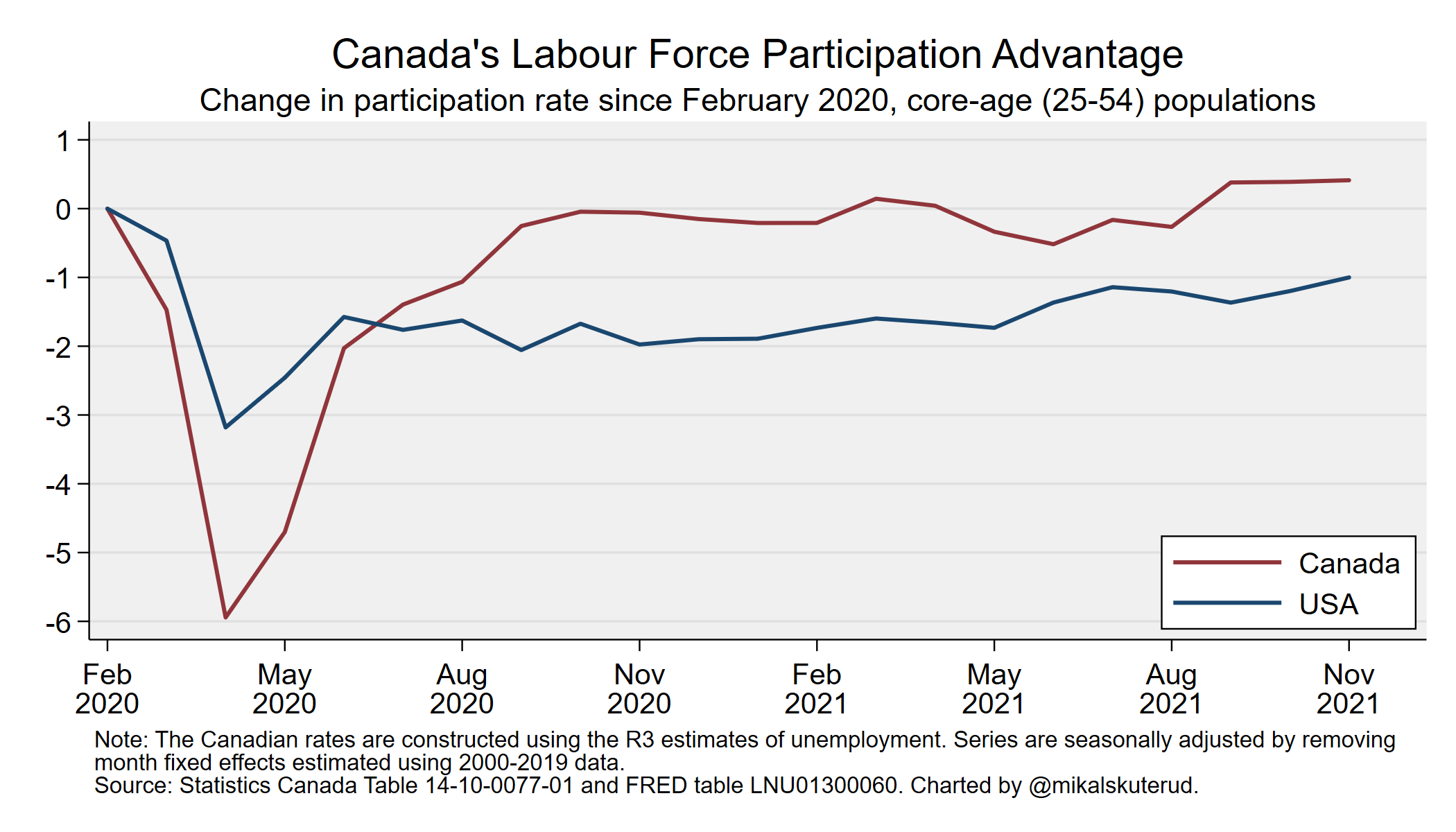

Advantage Canada

Mikal Skuterud, professor, Department of Economics, University of Waterloo @mikalskuterud

Results from Canada’s past three jobs reports suggest the COVID-19 pandemic boosted the labour force participation rates of prime-age Canadian workers to a historic high. Meanwhile, the pandemic shows worrying signs of having permanently dented participation rates in the United States. Canada and the U.S. define unemployment, and therefore labour force participation, differently.

Adjusting Canadian labour force participation rates to make them comparable to U.S. rates reveals a Canadian advantage dating back to 2001 that reached an all-time high of six percentage points in September 2021, a gap that has significant implications for economic growth. Will this gap close in 2022 or widen further as Canada invests in ambitious subsidized child care programs within provinces across the country?

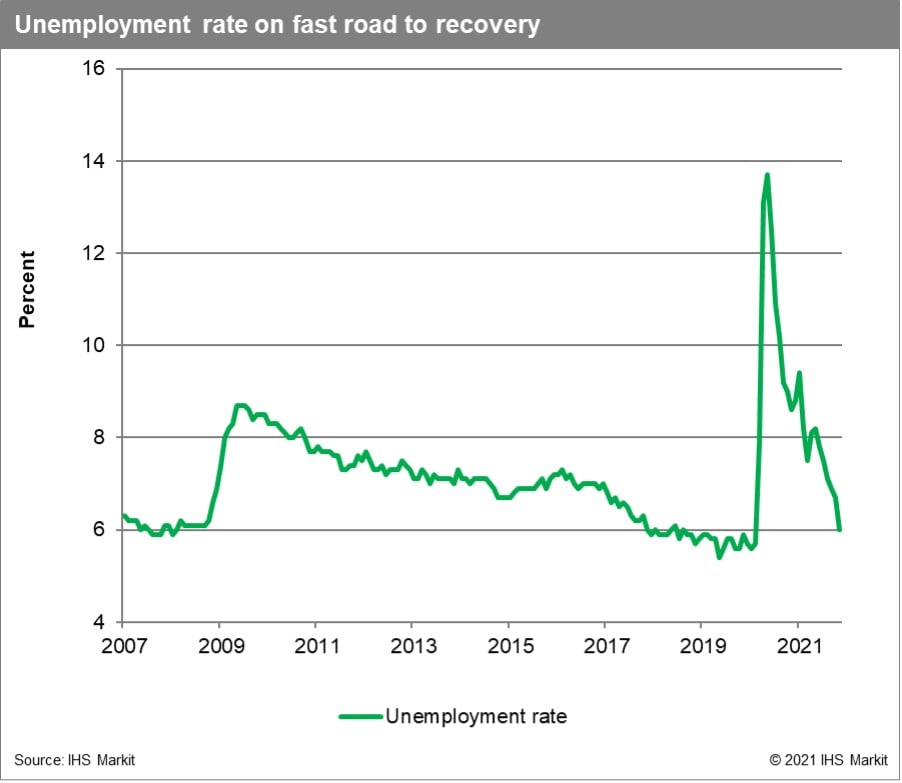

Canada’s labour market recovers, but what’s lagging?

Arlene Kish, director, IHS Markit Canada Economics

Canada’s labour market’s partial recovery in September 2021 was very welcome news. Total employment and the labour force participation rate returned to pre-pandemic (February 2020) levels. Yet, these broad employment indicators are just scratching the surface. Ideally, a full labour market recovery would be more favourable. In fact, this was highlighted by the Bank of Canada in the October Monetary Policy Report as it highlighted many other employment indicators that were lagging during the recovery (as of September).

Net employment gains were decent in October and surprisingly super-sized in November. As such, employment’s full recovery got more traction. Trailing behind are employment indicators like male full-time employment, female part-time employment, the male unemployment rate, and total low-wage employment. The labour force participation rate has pulled back slightly since September.

Unfortunately, the pandemic is not over yet. As such, proof of vaccination policies has helped drive up Canada’s vaccination rate. However, these same policies are resulting in job losses for those who are not vaccinated. Although the impact is anticipated to be small, it puts additional pressure on a tight labour market that is already dealing with labour shortages in several industries, namely construction, agriculture, health care, as well as food and accommodation. This could stall a robust job creation forecast of 3.6 per cent in 2022.

More on the unemployment rate…

Aaron Wudrick, director of domestic policy program, Macdonald-Laurier Institute

The pandemic may not be over, but Canada’s unemployment was down to six per cent by November 2020—already close to its pre-pandemic level of 5.7 per cent in February 2020 and on course to hit its all-time low of 5.4 per cent. That’s good news for many workers—the tighter labour market means wages are also rising—but without productivity rising, this ultimately means higher per-unit labour costs and upward pressure on prices for consumers.

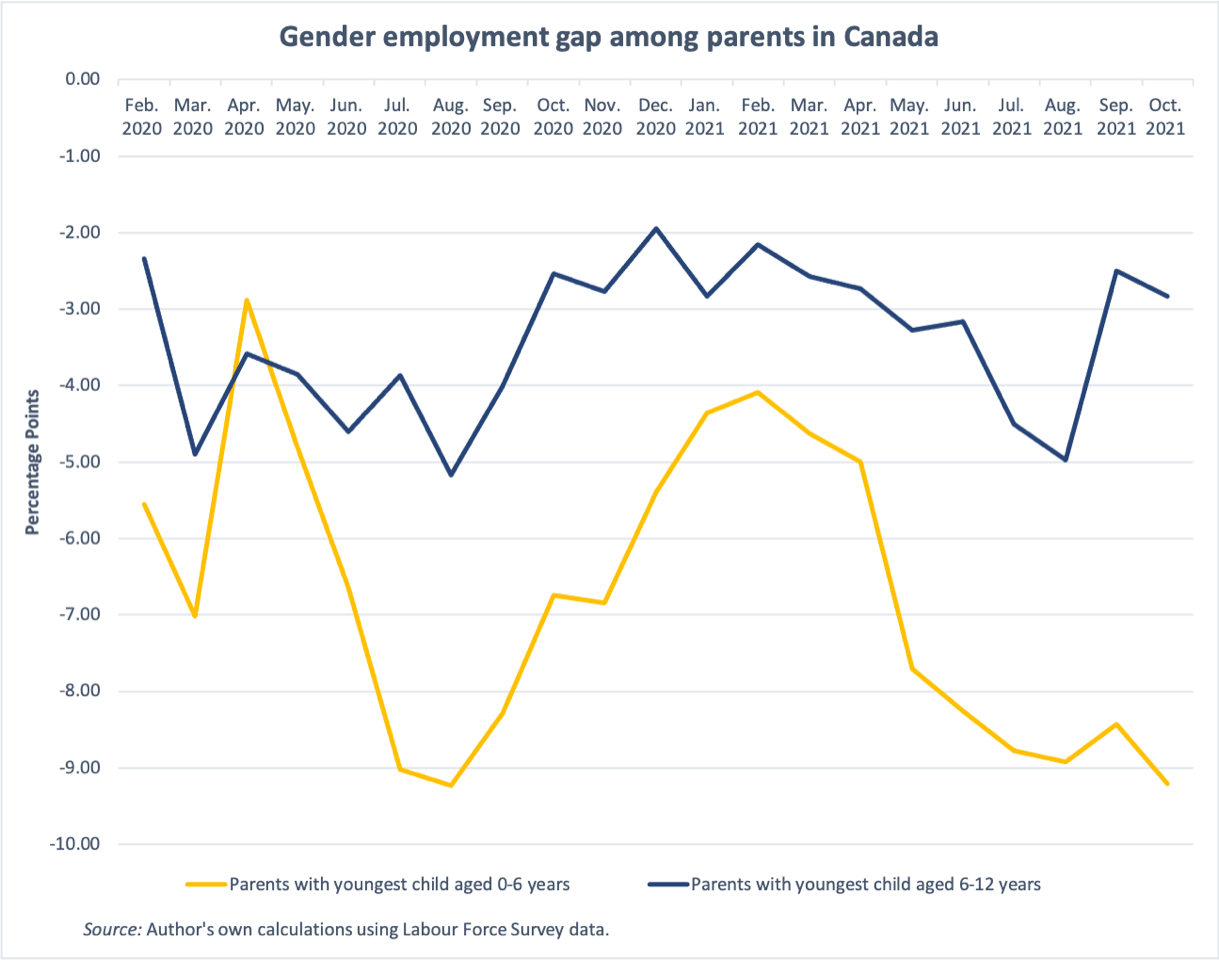

The mom-and-pop employment gap

Camille Simardone, assistant professor of economics, University of British Columbia Okanagan Campus

This chart shows the gender employment gap by month for parents with preschool-aged children (under 6 years) and parents with school-aged children (6-12 years). As of October 2021, the gender employment gap among parents with school-aged children has returned to approximately the pre-pandemic level—although, at three percentage points, the gap has not closed—whereas for parents with preschool-aged children, the gender employment gap has remained at around nine percentage points since July 2021. This implies that there may be lasting effects on the labour market outcomes of mothers with young children in Canada.

Given that demographic characteristics such as education and age, and job-specific characteristics such as occupation and full-time status are controlled in this analysis, typical explanations for the observed gender gap are insufficient. A possible explanation for the gap is that many mothers became the primary child care providers in the home when schools and child care centres closed due to the pandemic. Consequently, government policies that focus on supporting the return to work may neglect mothers. To ensure an economic recovery for all, and to ensure that existing gender inequalities in the labour market—such as the gender employment gap—do not persist, safe and affordable child care and parental leave will be essential for the economic recovery of women in Canada.

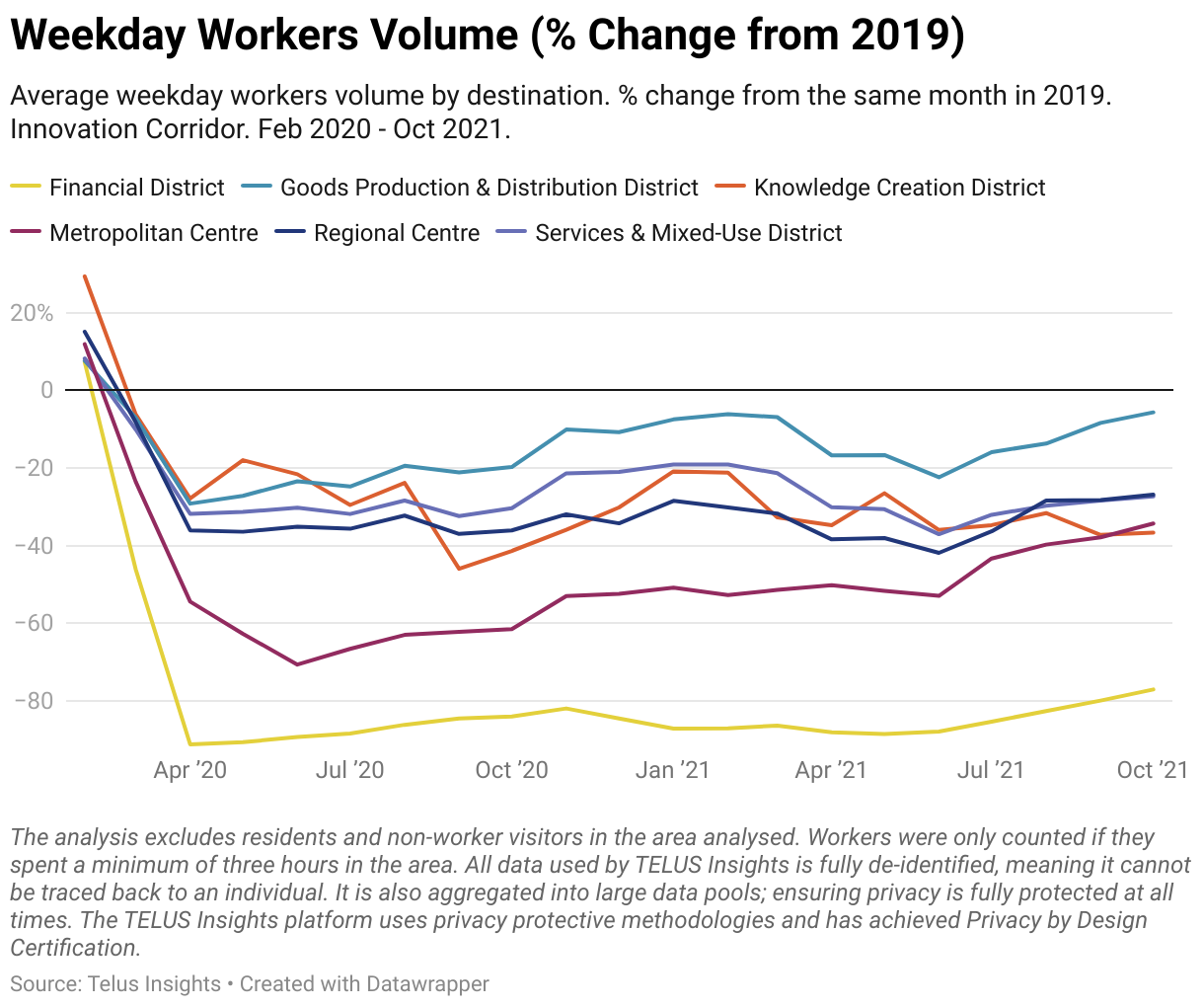

The Toronto-area work commute, remixed

Marcy Burchfield, vice-president; Saad Usmani, director of sector research; and Zaki Twaishi, director of data analytics, Economic Blueprint Institute, Toronto Region Board of Trade

The pandemic has caused significant changes to the volume and patterns of workers moving through the key employment zones in Ontario’s Innovation corridor, which consists of the five Census Metropolitan Areas (CMAs) of Oshawa, Toronto, Hamilton, Guelph and Kitchener-Cambridge-Waterloo—but it has not impacted all businesses or workers in the same ways. The Toronto Region Board of Trade has been using a business district framework to better understand the complexity and diversity of our region’s economy, the uneven impact of COVID-19, and strategies to support recovery, which is critical to ensure we’re putting the right resources and tools towards recovery. Most of these districts are dispersed through several metropolitan areas.

Using anonymized data from TELUS Insights, the board has been tracking the average volume of weekday workers in districts that serve different economic purposes, providing insights into pandemic recovery that can be used to identify policy needs and opportunities. Looking forward to 2022, this data will continue to provide valuable insights for measuring the evolving face of worker activity and foot traffic of daytime customers for local businesses through the pandemic recovery.

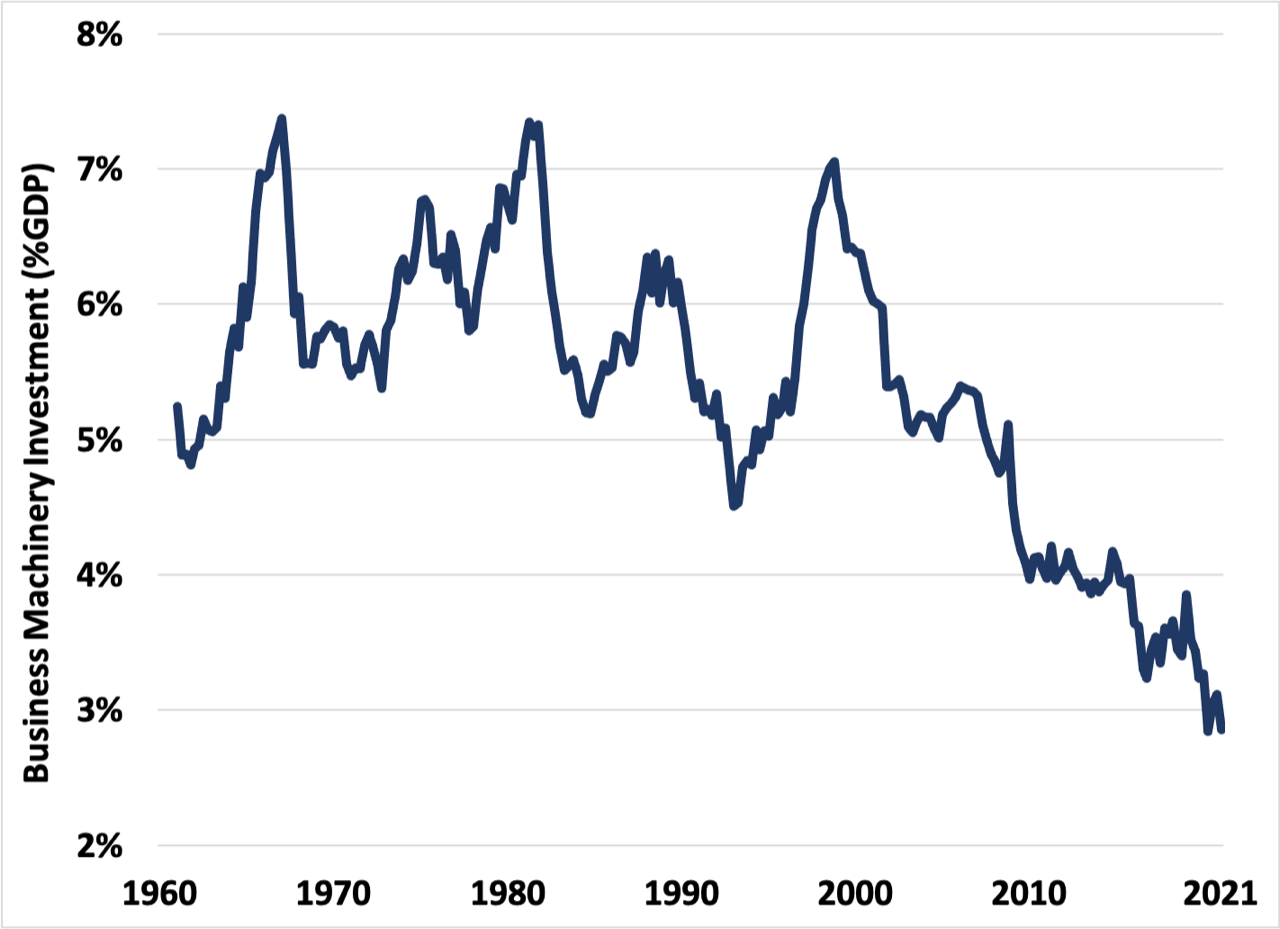

The robots are NOT coming (… and why that’s bad)

Jim Stanford, economist and director, Centre for Future Work @jimbostanford

“Future of work” discussions are usually dominated by fears about large numbers of workers being displaced by new technology: robots, automation, artificial intelligence, and other gizmos. It’s ironic, then, that Canadian businesses have been investing less in labour-saving technology—not more.

During the second half of the 20th Century, business investment in machinery and equipment (M&E) fluctuated between five and seven percent of GDP. Since 2000, however, it’s declined steadily—despite big corporate tax cuts purportedly intended to stimulate more investment. Many Canadian technology-intensive industries (like auto and aerospace) weakened, while the overall economy returned to an old-fashioned focus on resource extraction. Now, under COVID, machinery investment has languished below three per cent of GDP: half its traditional pace.

If the robots aren’t coming, does that mean our jobs are safe? Not exactly. Investing in machinery has both negative and positive employment effects. Some workers can certainly be replaced by machines. But across the economy, strong M&E investment improves aggregate demand and export competitiveness—and sparks new jobs designing, building, operating, and maintaining all that technology. On a net basis, there’s a mild positive correlation between M&E investment and stronger job-creation.

So perhaps Canadian workers should cross their fingers for that long-feared invasion of robots. It would be a sign that Canadian businesses have finally rediscovered their work ethic, and are getting up off the couch to invest again in a higher-tech future.

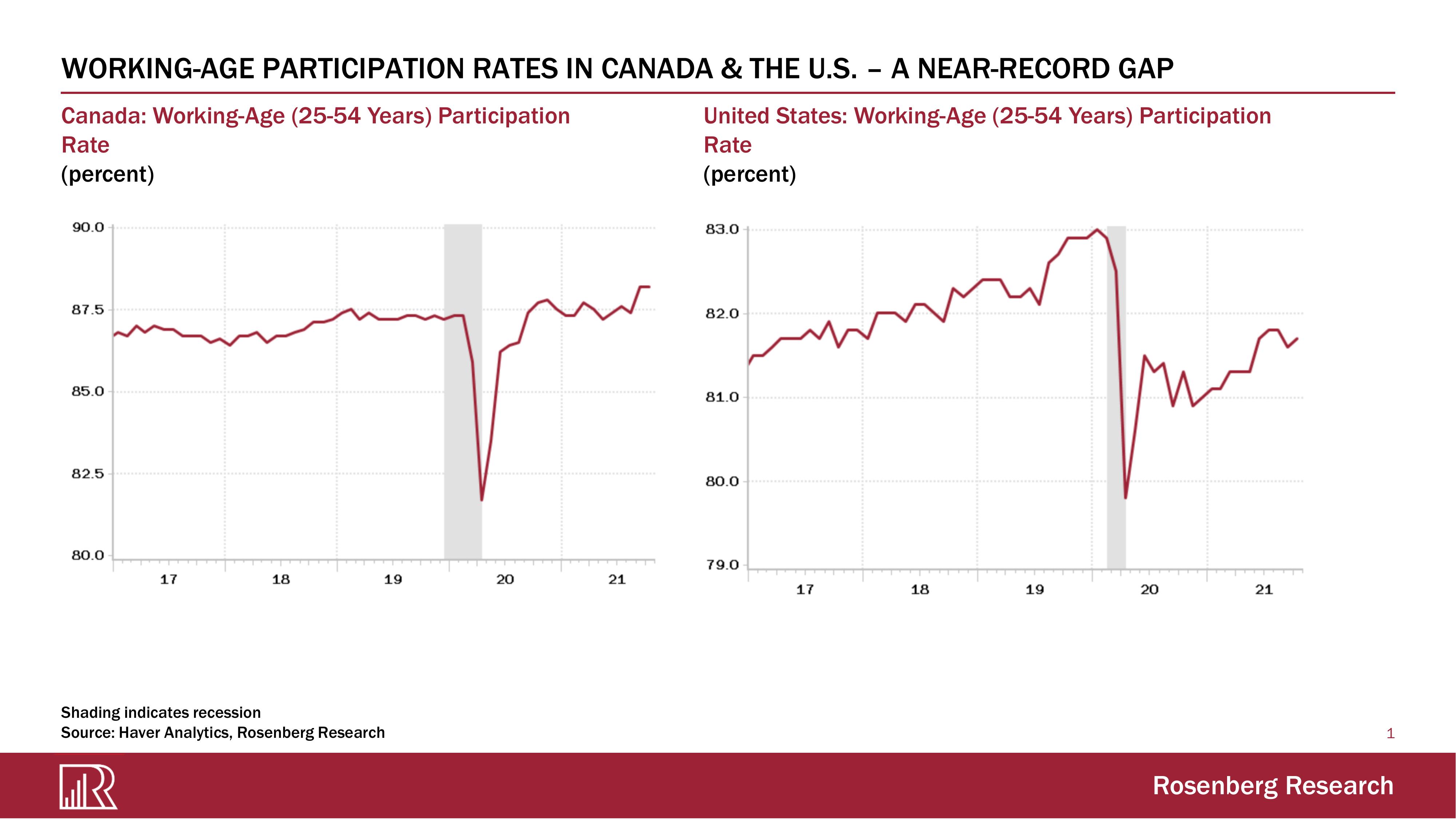

A tale of two labour markets

David Rosenberg, chief economist and strategist, Rosenberg Research & Associates Inc.

I’m talking about the United States and Canada — two economies joined at the hip (except for the fact that Canada’s vaccination rate is now nearly 20 percentage points higher than is the case stateside — and that is the main reason why competition for jobs in Canada is so much stronger and why wage growth, as a result, is running nearly 300 basis points lower).

But there is a gap between labor market performance worth noting yet again. The U.S. participation rate at 61.6 per cent has recouped barely more than 40 per cent of the pandemic and lockdown plunge in 2020. It is quite a bit away from the 63.4 per cent pre-crisis peak and that goes a long way towards explaining how the unemployment rate has managed to plunge all the way to 4.6 per cent — the unemployment rate has reversed 90 per cent of the run-up. The participation rate for the prime working-age population, at 81.7 per cent, has only recouped 60 per cent of the pandemic decline — so this isn’t just about the “retirement effect.” And we have the year-over-year trend in wages at nearly five per cent and the inflationists are howling.

In Canada, the participation rate and the prime working age component have recovered 96 per cent of the decline (actually, 98 per cent for the latter) so these are practically back to pre-COVID-19 levels. The unemployment rate hasn’t quite recovered as a result as has been the case in the U.S., with the Canadian jobless rate at 6.7 per cent). As such, wage growth in Canada is running at less than half of what it is in the U.S., at two per cent. Go figure.

I guess the low-skilled workers in the leisure/hospitality and retail sectors north of the border don’t realize just how much bargaining power they have, or perhaps Canadians haven’t gone long on the stock market to such an extent that they can live work-free off their portfolio. Or maybe, just maybe, the Canucks now beat the Yanks when it comes down to good old-fashioned work ethic!

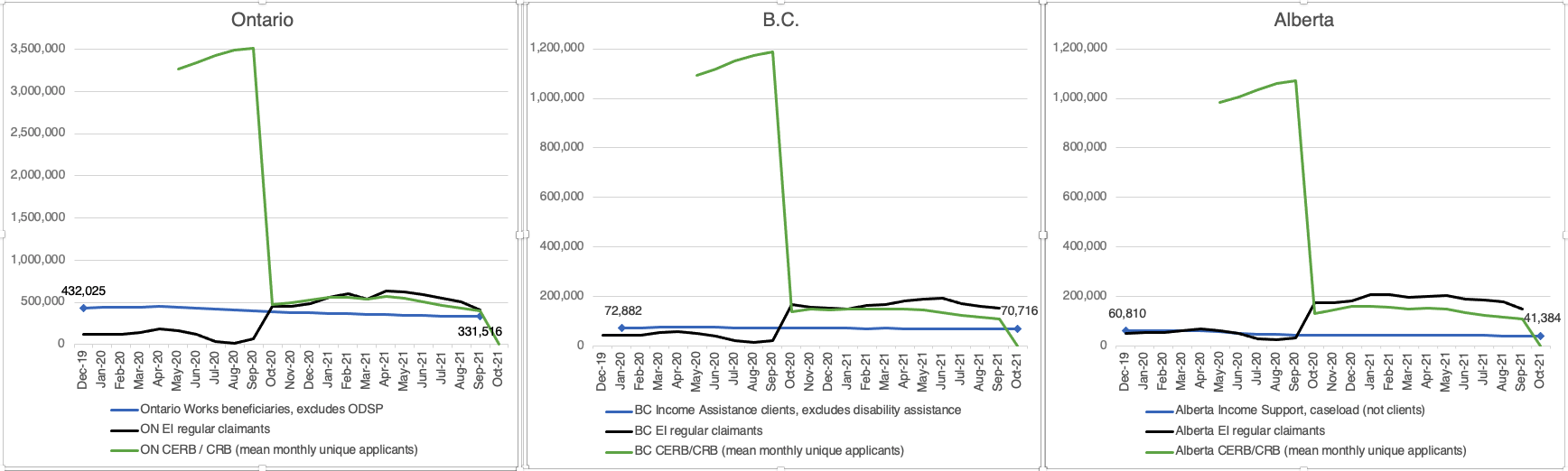

Is a pandemic a good time to cut your welfare rolls?

Jennifer Robson, associate professor of political management, Kroeger College, Carleton University @jenniferrobson8

Sources: Author’s calculations using Statistics Canada Table 14-10-0011-0; Ontario Ministry of Community and Social Services, Ontario Works Monthly Statistical Report – September 2021; B.C. Ministry of Social Development and Poverty Reduction, Monthly caseload data; Government of Alberta, Income Support Caseload data, open data; Canada Revenue Agency, Detailed data about CRB applications, Table 6; Employment and Social Development Canada, CERB Total Unique applicants by province/territory and gender.

We all know that the federal spending on pandemic aid in the form of income support has been extraordinary. For a time, it meant that people in sudden financial need didn’t have to contemplate our system of last resort—provincial welfare. It also meant that provinces got some financial relief from lower caseloads and the attendant administrative costs of policing benefit recipients. But, as illustrated on the green lines in the three provincial examples above, those days are over. Federal income support to workers outside of employment insurance (EI) will be available, according to Bill C-2, only for localized shutdowns due to COVID. The taps were not going to stay on forever.

The EI caseload (shown in black), remains higher than the pre-pandemic trend, but it is still EI. When benefits are exhausted, that’s it. You have to find insurable work to get coverage again. Usually some important share of EI exhausters fall through the system and land on provincial welfare rolls, where the road back to paid work and self-sufficiency is too often filled with obstacles and landmines. Relative to December 2019, there are nearly 100,000 fewer clients on Ontario Works and 20,000 fewer income support cases in Alberta. Who would have thought a pandemic and recession was a good time to cut welfare rolls? But in the months ahead, we should keep an eye on what happens to those caseloads. I’ve heard whispers they are already rising in Toronto.

For a Conservative government facing election in 2022 or 2023, there is no better time to politicize and weaponize social assistance than when caseloads have risen substantially. This is not, by the way, an argument for basic income. It is, instead, a call to pay close attention to the potential labour and human capital we could lose to a dead-end system that isn’t built for workers but is ripe for political cheap shots in the months and years ahead.

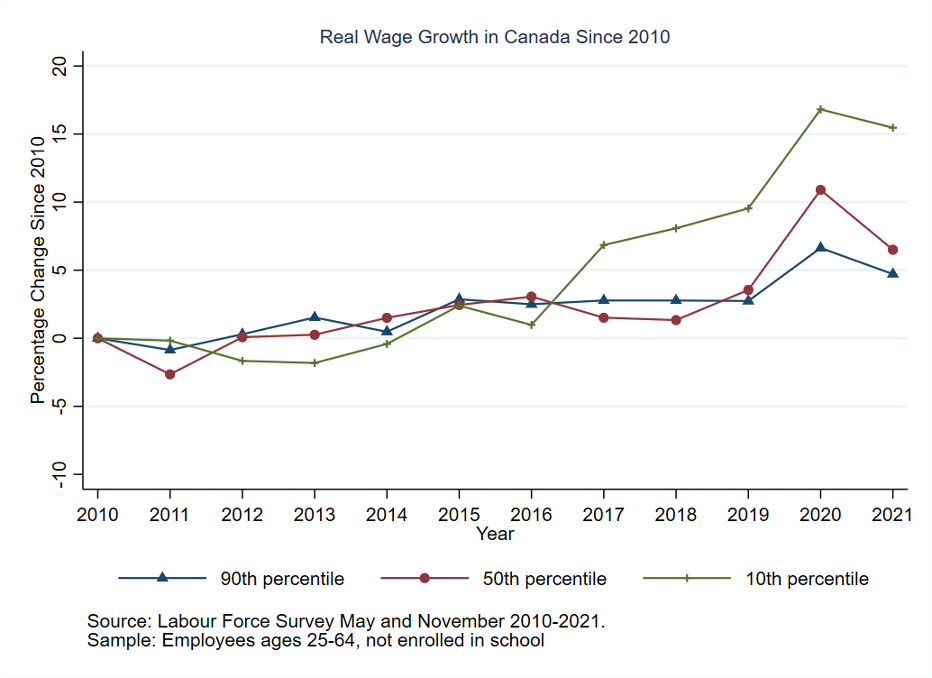

Wage inequality has narrowed. Will that last?

Kelly Foley, associate professor in economics; and Nathanael Hammond, graduate student in economics, University of Saskatchewan @foley_kelly

In the second half of the 2010s, wage growth among those earning wages in the bottom 10 per cent began to outpace growth among higher-wage employees. Between 2016 and 2019, wages at the 10th percentile grew by almost 10 per cent, in part because of substantial minimum wage increases in some of the largest provinces. The difference in relative growth meant that wage inequality was narrowing during this period.

Wages are not the best measure of well-being because the number of hours worked, and the stability of those hours, are important in determining a family’s income. However, what wages do signal is how work is valued in the labour market, and the fairness of that evaluation is one reason to care about wage inequality.

In 2020, following the initial COVID-19 lockdowns, the pace of growth at the top, bottom, and middle of the distribution accelerated dramatically. Then, between 2020 and 2021, nominal wages were roughly the same, but, because inflation grew, real wages fell. Some of the factors driving up wages, such as frictions in matching workers’ skills to employers’ demand, are likely temporary. As those issues are resolved, we’ll be watching to see if the wage gains at the bottom of the distribution are eroded. While the essential nature of low-wage work was highlighted by the pandemic, the services provided at the lowest wages, including jobs in retail and care facilities, were always vital, and now entail new risks. Higher wages in these essential sectors should reflect that value and will hopefully persist.

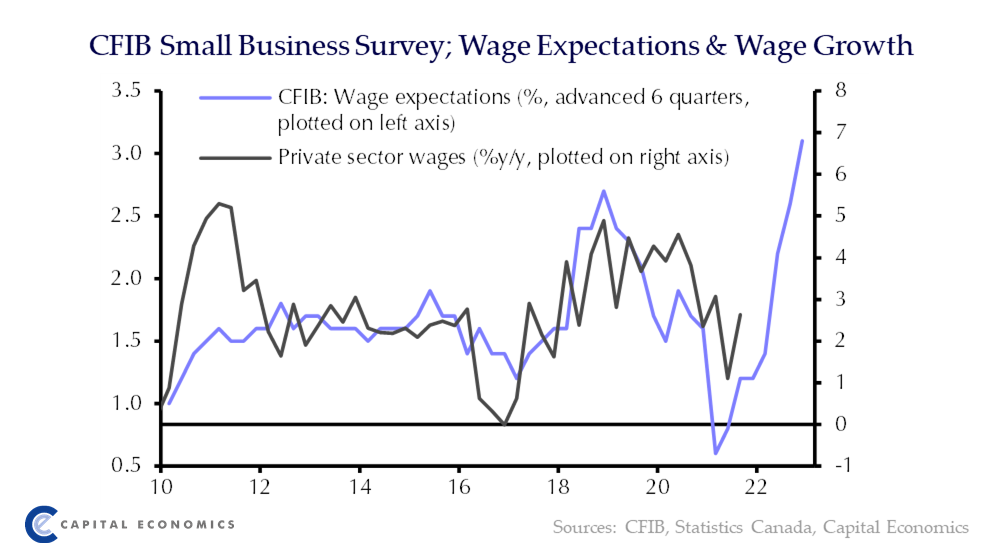

Great(er) expectations

Stephen Brown, senior Canada economist, Capital Economics

Inflation has soared to almost five per cent in recent months but, until recently, the Bank of Canada was not at all concerned about this high rate being sustained. That’s because the current high rate of inflation is mainly due to factors that the Bank judges to be temporary, such as the various supply disruptions caused by coronavirus outbreaks in key manufacturing countries. Inflationary dynamics are likely to be very different in 2022, however.

As this chart shows, due to widespread labour shortages, companies across Canada (as surveyed by the Canadian Federation of Independent Businesses) expect wages to increase at rates we have not seen for decades. While higher wage growth sounds like a good thing, the issue is that large parts of the economy are already approaching their full capacity. Given these capacity constraints, an increase in workers’ spending power is more likely to lead to higher inflation than it is to boost real activity further. If wage growth rises strongly, the Bank of Canada will therefore become concerned about inflation being sustained at a rate above the official two per cent target and the Bank could be forced to raise interest rates very sharply to try to slow the economy and reduce the extent to which firms push wages further. If that happens, watch out for negative consequences of higher borrowing costs on the housing market.

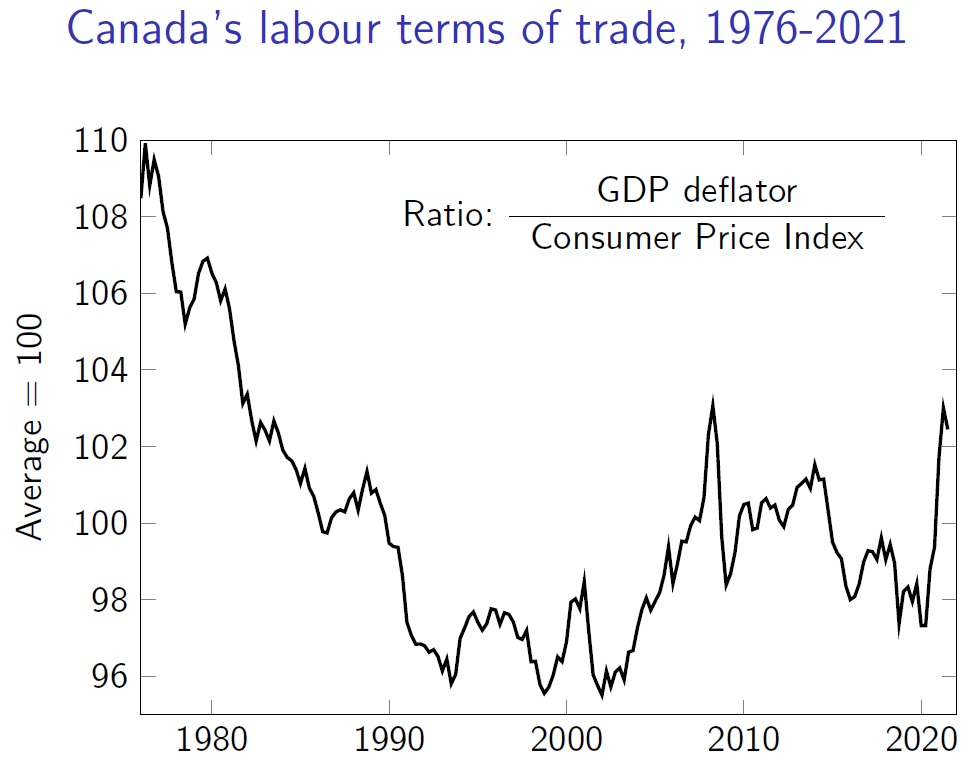

Will wages keep pace with inflation?

Stephen Gordon, professor, Department of Economics, Université Laval @stephenfgordon

Economic theory says that real wages will track productivity, and this prediction has largely been consistent with the data. This doesn’t necessarily mean that workers’ purchasing power will track productivity, though. Wages increase in line with output prices, but what matters for workers’ standards of living is consumer prices.

The ratios of producer to consumer prices are the labour terms of trade. If the prices of what workers are buying rise more quickly than the prices of what they are producing, then the labour terms of trade fall and their real purchasing power may decline, even if productivity continues to increase. Much of the decline in Canadian real incomes after 1976 can be attributed to a sharp decline in Canada’s labour terms of trade: producing more won’t make you better off if no one wants to buy what you’re making. The recovery in real incomes in the 2000s coincided with the resource boom and an improvement in Canada’s labour terms of trade.

Consumer prices increased by four per cent between the third quarters of 2020 and 2021, but producer prices—as measured by the GDP deflator—increased by eight per cent. As a result, Canada’s labour terms of trade have now increased to levels last observed during the resource boom.

If the labour terms of trade remain at these levels or increase even further, then Canadian workers’ purchasing power should increase, even if consumer price inflation persists. If not, well, maybe not.

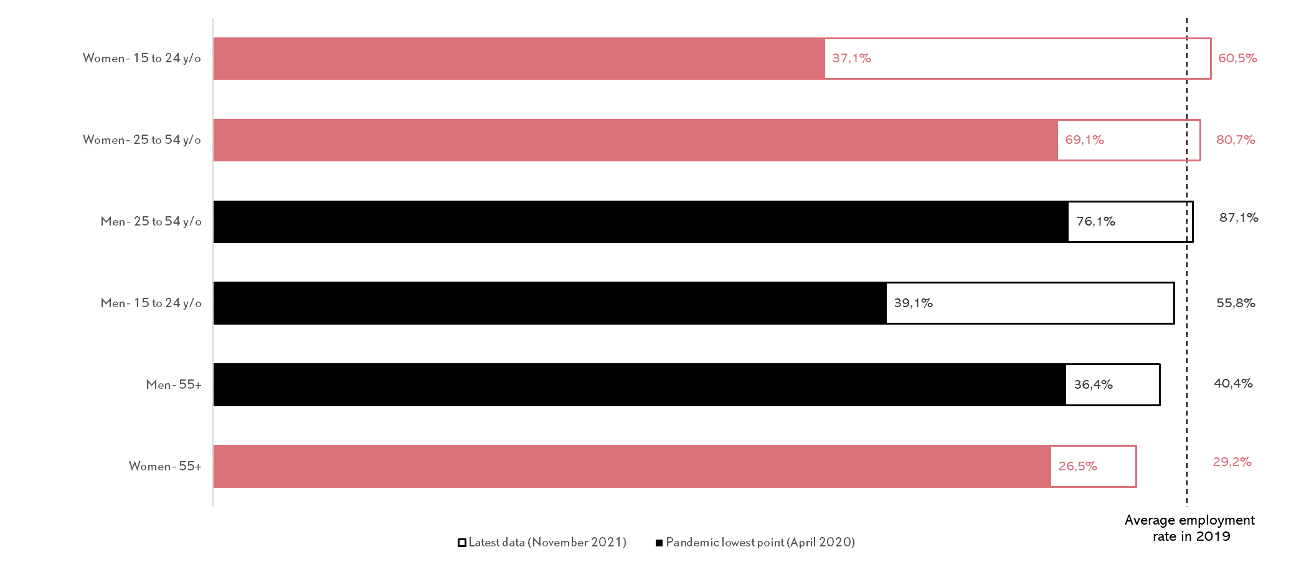

The job market bounces back

Emna Braham, deputy director; and Simon Savard, senior economist, Institut du Québec @EmnaBraham @SimonSavard3

The first wave of the pandemic hit the job market hard, and it hurt women even harder. In April 2020, the employment rate for core working age women (25 to 54 years old) was 12 percentage points below its pre-pandemic level (2019 average). For young women (15 to 24 years old), the cut was even deeper—23 percentage points—bringing some to call it the first ever she-cession.

Since then, the figures changed with the different restrictions put in place, each harming different groups of Canadians. In the summer of 2020 with looser restrictions and strong income support still in place, some were concerned about young Canadians opting out of the labour market.

Today, the job market recovery is undeniable, with employment on the rise, unemployment plummeting and record job vacancies. The good news is that it is not leaving women behind. For both core working age and young women, employment rate more than recoups its pandemic losses. For men aged 25 to 54 years old, the recuperation is also complete.

However, some concerns remain for young men as well as older workers whose employment rates are still below what was seen in 2019. Next year, close attention must be paid to these groups. With labour market tightening, low employment rates might be more about supply (people choosing not to go back to work) than demand (lack of job opportunities).

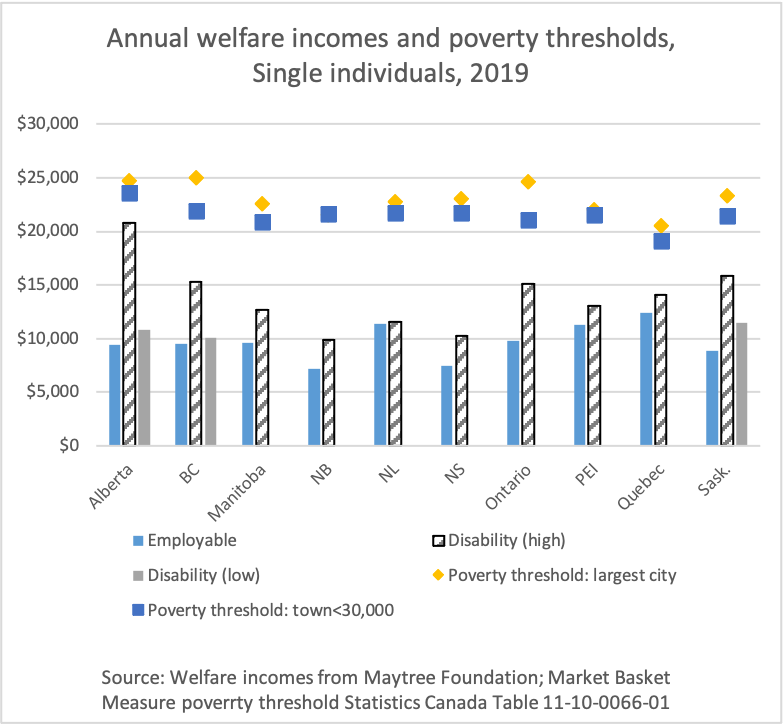

Why a Canada Disability Benefit is no cure-all

Frances Woolley, professor, Department of Economics, Carleton University @franceswoolley

Welfare incomes for people with disabilities—provincial social assistance benefits plus federal and provincial tax credits—are below Canada’s poverty threshold. The federal Liberal government has committed to creating a new Canada Disability Benefit, intended to reduce poverty among disabled working-age adults.

A Canada Disability Credit would widen the already large gaps between the welfare incomes available to individuals deemed employable and those with disabilities. Since the criteria for deciding who qualifies for disability benefits are opaque and vary across provinces, people may fall into the “employable” category because they do not know the “right” way to answer screening questions, or because they lack effective advocates. The history of the Disability Tax Credit does not inspire confidence in the federal government’s ability to target disability benefits to those who need them.

A Canada Disability Benefit is seen by some advocates as a step toward a basic income for the disabled. As such, it would suffer from the limitations of any basic income. It would not recognize that living in Vancouver costs more than living in small-town Quebec. Provincial social assistance programs often provide some in-kind benefits. For example, Ontario pays for diabetic supplies. Would a Canada disability credit recognize that some disabilities are more expensive than others? Would it help a cognitively impaired person figure out how to access supports and services?

Unfortunately, cash transfers do little to address the structural challenges people with disabilities face in procuring all the necessities of life.

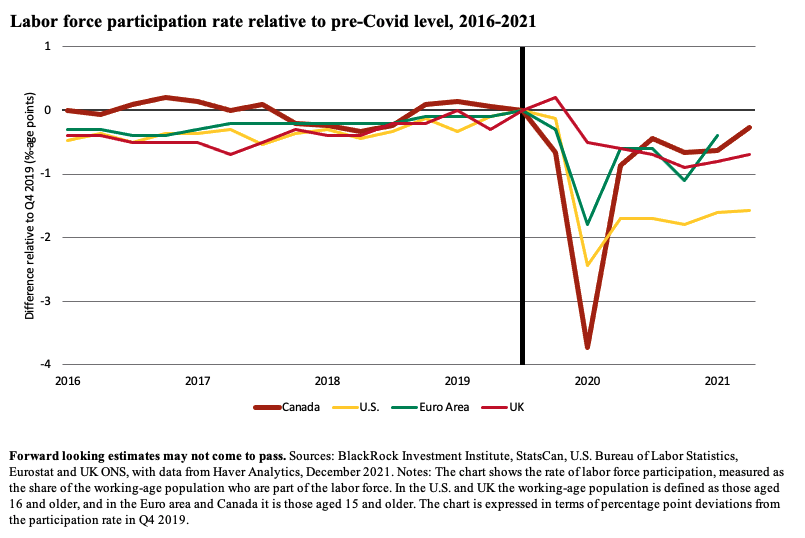

Canada’s back (to work more)

Kurt Reiman, senior strategist for North America, BlackRock Investment Institute

With output exceeding its pre-pandemic level in the United States, the rates outlook will be shaped by what happens to its labour participation that has yet to recover. In Canada it is the flipside. Its labour force participation rate has nearly fully reversed its steep pandemic decline. Yet economic output hasn’t returned to its pre-pandemic level, and older and lower-wage workers, as well as those without a university degree, have been slow to return to the job market.

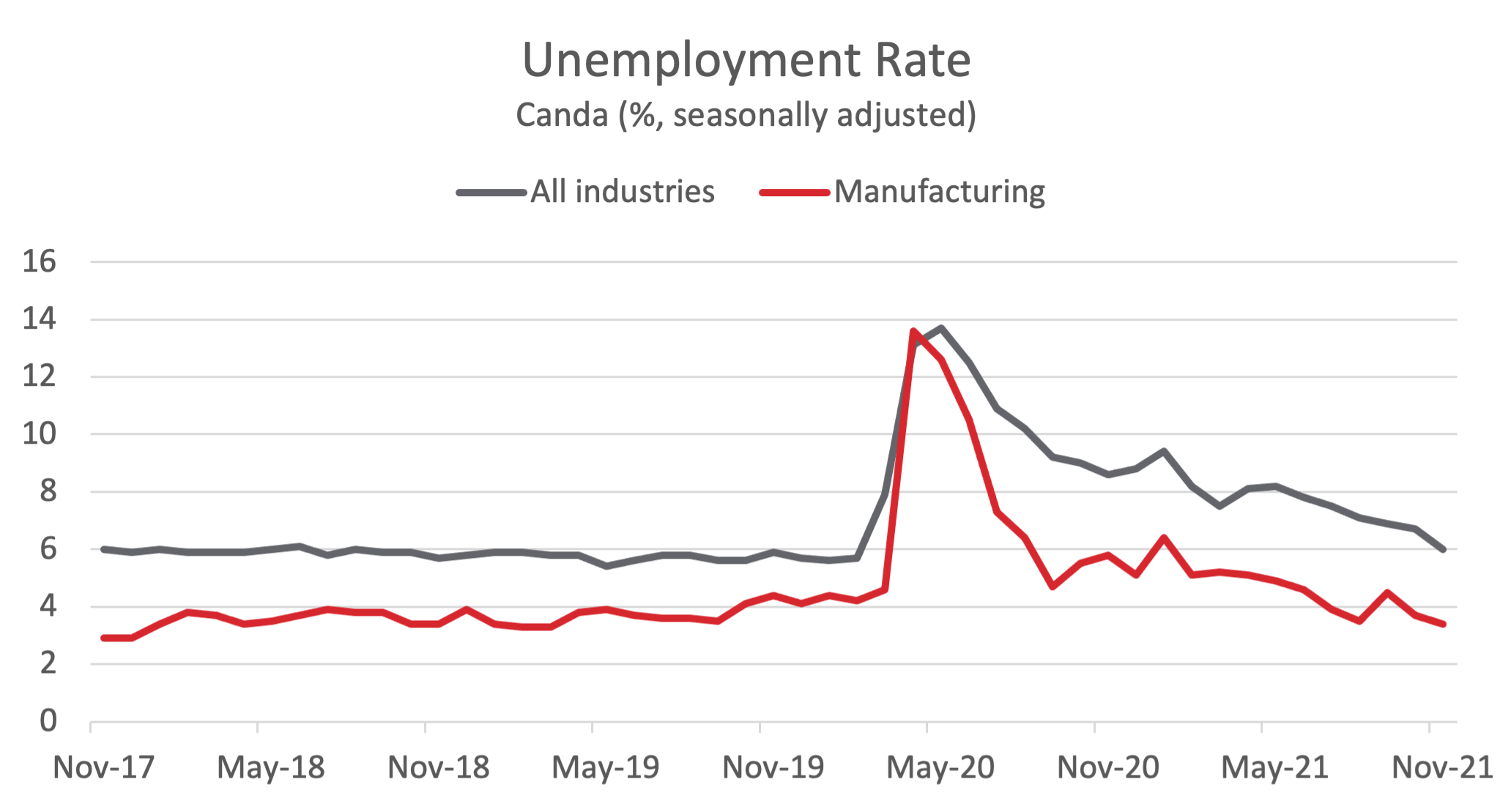

Worker shortage isn’t new for manufacturers

Alan Arcand, chief economist, Canadian Manufacturers and Exporters @AlanArcand

Even in normal times, labour and skills shortages are a chronic issue for Canada’s manufacturers. Unfortunately, the extreme circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic have only exacerbated the situation. In a recent Canadian Manufacturers and Exporters (CME) survey, 77 per cent of manufacturers identified attracting and retaining a quality workforce as their top challenge, putting it ahead of the ongoing supply-chain disruptions that are also weighing heavily on the industry.

To be sure, firms in many industries have reported difficulties filling vacant positions, but this challenge is especially pronounced in the manufacturing sector. In November, the unemployment rate in the sector fell to 3.4 per cent, the lowest level since March 2019 and 2.6 percentage points below the all-industry average. With the number of job vacancies in manufacturing also at a record high, the inability to find enough workers is clearly hampering the sector’s recovery. By extension, it is also limiting the production of key goods, driving up consumer costs, and restraining Canada’s overall economic growth. (Manufacturing is the second-largest industry in Canada, accounting for about 10 per cent of GDP).

Although the pandemic-related labour force disruptions will eventually dissipate, the challenge of labour and skills shortages is not going to go away any time soon. Canada’s population is rapidly aging and not enough young Canadians are choosing to pursue a career in manufacturing. That is why CME continues to work with all levels of government to enact policies that expand the manufacturing labour pool.