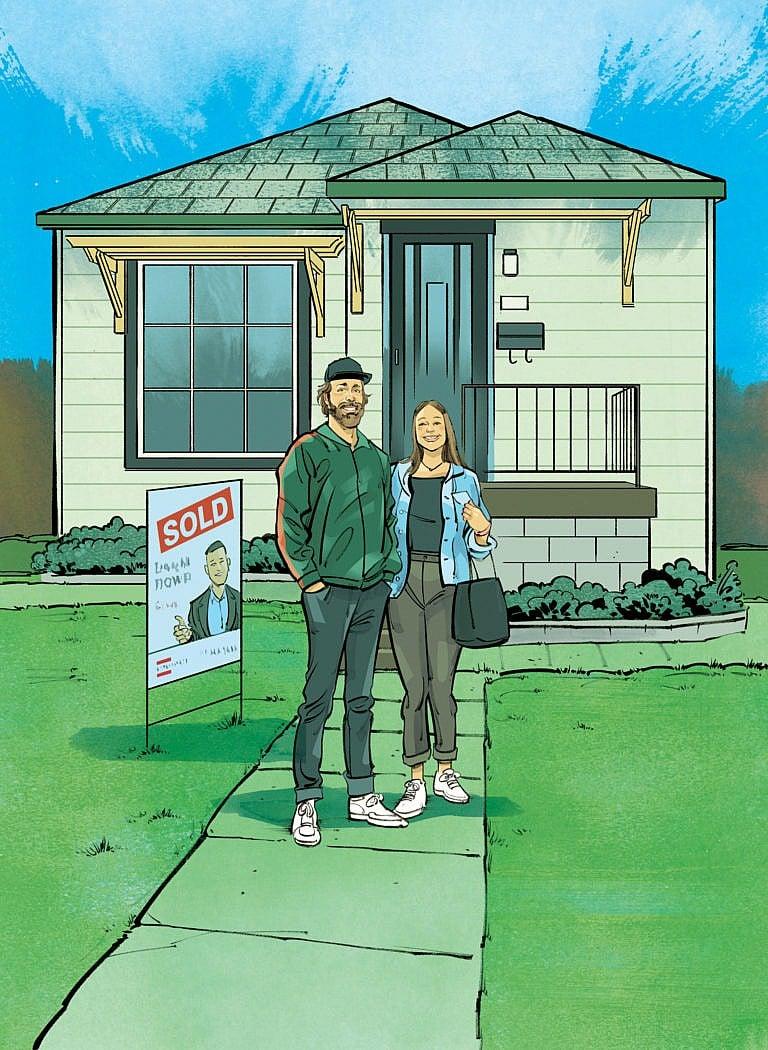

Want to buy a house? Don’t bother checking the foundations.

Buyers desperate to get in on the property boom are opting out of home inspections, opening the door to nasty surprises

(Illustration by Kagan McLeod)

Share

In May 2021, Molly Fleming and her brother Matthew leaped into southern Ontario’s pandemic-fuelled real estate frenzy, buying a postwar bungalow in Hamilton they intended to use as an investment property. First-time homebuyers both, they paid above the $500,000 asking price for the modest property. A couple of months after they took possession, their new upstairs tenant called to complain about a musty smell wafting from the closet.

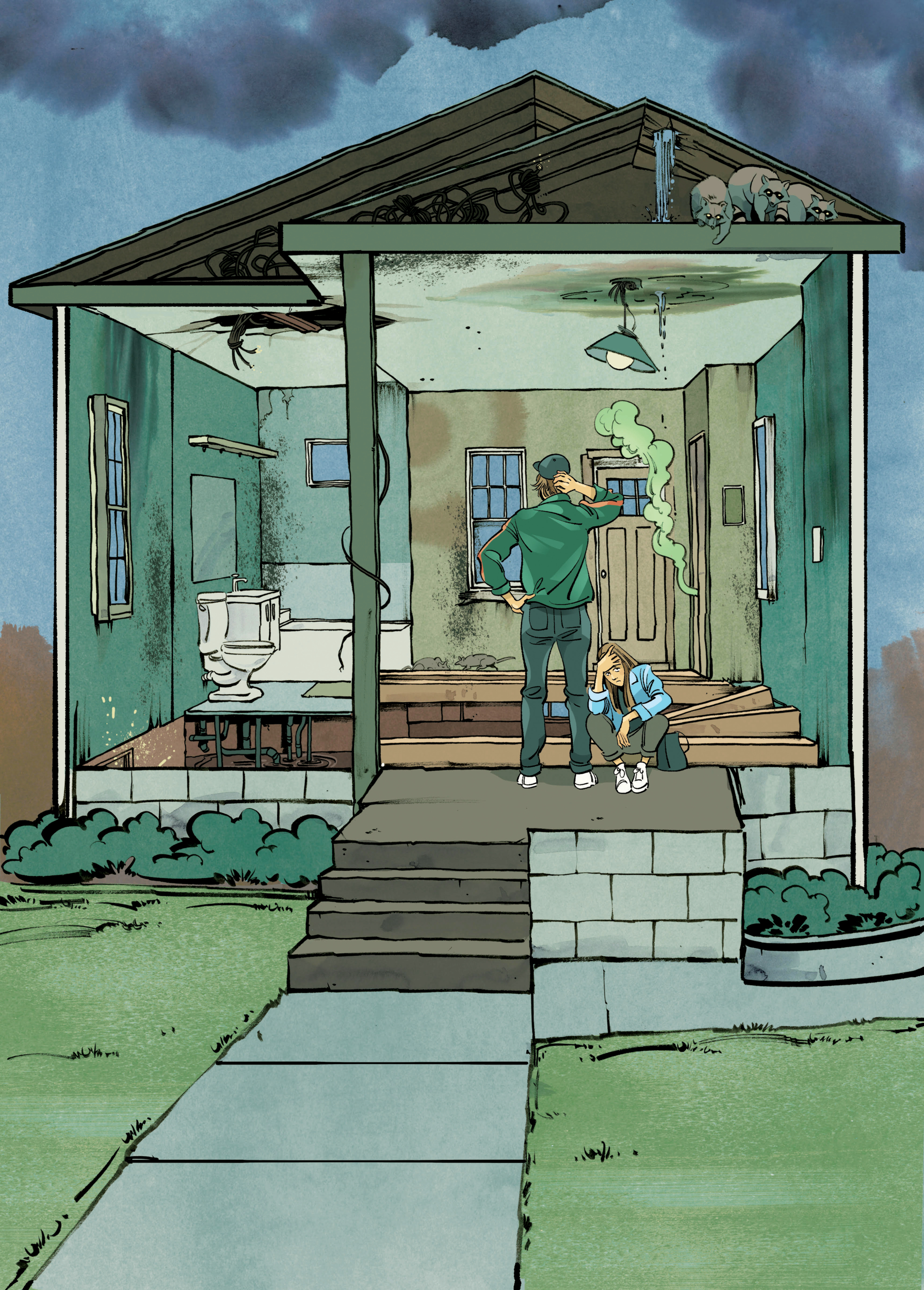

Molly went to investigate, and soon spotted other worrying issues they hadn’t noticed on their only walk-through before they bid: a water stain on the living room ceiling; a shower window with a rotting wooden frame. They called in a professional mould inspector, who confirmed the bad news. “There was a lot of mould,” Matthew says. “It was significantly worse than we thought. I think there’d been a leak in the attic for decades.”

The day after the inspector left, the tenants called again: when they turned on the dryer, sparks would fly around inside the drum. Molly immediately purchased a new one, which was barely installed when the tenants reported the washing machine was emitting a burning smell. The Flemings replaced the washer, too.

MORE: Nowhere to buy

It was hard to know what fresh horror would confront them the next time the phone rang—not least, Matthew says, because the siblings had foregone a buyer’s home inspection. Their realtor told them that, in a red-hot market, there was no way they’d win a bidding war for the house if they made the purchase conditional on an inspection. Instead, the pair put money into a buffer account to pay for anything that came up, like roof replacement or landscaping. “But once one thing starts rolling, it seems like a snowball effect,” Molly says.

The Flemings’ story is a familiar one at a time when Canadians are so desperate to get into the real estate market that they’re throwing aside the once-routine precaution of a house inspection. They see the decision as a necessary gamble, but many are left in the dark after they’ve made the biggest investments of their lives—or shelling out after they’ve already drained their savings.

The pressure to waive inspections is a great enough concern that the federal Liberals promised during last summer’s election campaign to introduce a legal right to them, a pledge that has made little impression on property-hungry Canadians. If they wait for Parliament to flesh out the details, prices will only soar further. Meanwhile, prospective buyers who insist on inspection clauses are having their bids rebuffed time and again.

There is no data on how many homes are sold in Canada without inspections, but John Pasalis, president of Toronto-based brokerage Realosophy, offers a simple estimate: “If 70 per cent of homes are selling for over the asking price, I’m confident that 70 per cent of the sales had no condition of a home inspection. It goes up and down based on how competitive the market is.”

And the market in some cities has been competitive for a decade or more. In the early days of Toronto’s boom, when bidding wars first became commonplace, routine inspections turned into an unforeseen logistical hassle because every prospective buyer would demand one the day before offers were due. “You’d have 10 home inspectors falling all over each other doing inspections on the same home,” Pasalis says. “If there’s 10 people who bid on the home, one benefited from that inspection. The other nine just wasted 500 bucks.”

To streamline the process, some selling agents had pre-listing inspections done that they could share with prospective buyers, a practice that remains common. These buildings might then be sold without the home inspection clause, Pasalis says, but at least someone has assessed them.

The practice has downsides, though—most obviously that the inspectors are accountable not to the people who might live in the house but to sellers looking for the highest possible price. If the inspector missed something, the new homeowners have little legal recourse.

What’s more, says Andy Christie, owner of Safe Homes Canada, an inspection service based in Barrie, Ont., some listing agents are not fans of rigorous home inspectors. “They think we create problems for them because we find all the deficiencies,” he says. Last summer, Christie was doing an inspection for a client looking to buy a century home in Newmarket, Ont. The seller’s inspection report suggested the house was fine, but Christie discovered that most of the crawl spaces were inaccessible, making it almost impossible to assess the foundation or floor structure. Any repair work down there would be costly and difficult.

In the end, Christie got far enough under the home to glimpse a beam with a bow in it. “Probably rotted,” he thought. His final verdict: the house was what he charitably calls an “informal structure.” He says, “Everything we could see was bad—and we couldn’t see most of it.” So he persuaded his clients not to buy it. Days later, Christie drove by to see a “sold” sign in front of the home and now wonders if whoever bought it was aware of the sagging, shifting or cracking that was sure to come. “Buyers are getting screwed every day,” he says.

The current home inspection industry took shape in the 1970s, a creation of liability-conscious realtors. “It was a way for them to say, ‘We don’t want to take the responsibility if you move in and the furnace is kaput or the structural beam up the middle of the house is not properly supported,’ ” says Peter Weeks, president of the Canadian Association of Home and Property Inspectors. Some would hire a contractor to look for such things, and that practice evolved into a dedicated service. But with no licensing, formal education requirements or professional guidelines, home inspectors were viewed with skepticism in those early days.

The industry is now held in higher regard, though licensing and training requirements aren’t standardized across the country. “You could start a home inspection company in Ontario tomorrow,” says Weeks. As a result, the reliable ones must compete with a wide pool of cheaper, less experienced inspectors when demand for their services shrinks.

Still, as some inspectors bemoan the drop in demand for their services, others are catering to selling agents, tailoring pre-listing home inspections to serve as marketing tools. In a presentation posted to his YouTube account, David Asselin, a Vancouver-based inspector who specializes in sellers’ inspections, likens his work to real estate photography, saying, “We’re there to facilitate the sale of the house.”

Asselin says his company distinguishes itself from others by reporting the positive aspects of a house—a brand-new roof, say, or a hot water tank that’s only a few years old. But it also includes all the problems that a buyer’s inspection would, he says, allowing bidders to weigh the flaws of a property against its virtues. “Most inspectors are so negative out there, and they’ll try to show the client how much knowledge they have,” Asselin says. “We give the client the full picture of what’s happening.”

***

The bad news for Molly and Matthew Fleming: extensive work to remove mould from the bathroom, attic and closet of their Hamilton property was going to cost more than $10,000. Moreover, because their tenant would have to move out during the work, they wouldn’t have rent money to help offset the cost.

It could have been worse. In nearby Halton Hills, Lisa Song had the chance to buy her country dream home in early 2020; but only if she passed on a home inspection, the listing agent told her. After they moved in, Song and her family discovered defects, like a lack of well water being pumped into the house and major problems with the septic system. Cost of repairs: more than $120,000. “I almost fell to pieces knowing I would have to get a mortgage to fix the septic,” Song told CTV News.

While the bidding wars of the pandemic period have put a spotlight on the problem, such stories were circulating long before COVID struck. Back in 2016, Matthew Noel inherited some money after his father died, so he and his mom, Wendy Ettinger, set their eyes on a newly built five-bedroom in Nanaimo, B.C., listed for $440,000. Knowing a bidding war was likely, they made an offer over asking and waived the home inspection clause.

Six months after moving in— Ettinger to the basement suite; her son upstairs— the two of them started to feel sick, and noticed a musty smell that kept getting worse. The duo bought a ladder and poked their heads into the attic, where they spotted mould. They hired a private investigator, who learned that construction on their so-called newly built home had actually started eight years before they bought it; the house had sat unfinished for years, its construction delayed by the 2009 recession.

Ettinger and her son moved out for the sake of their health, and when they finally sold the home years later, she says, they failed to reap the huge profit their neighbours were gaining in the resurgent B.C. housing market. They got roughly what they paid for it, Ettinger says, adding: “We had to disclose everything.”

What a seller is required to disclose varies depending on the province, and the rules are an imperfect backstop. In Ontario, vendors are required to disclose any concealed defects they know of that render a property unsafe to live in, says Bob Aaron, a Toronto real estate lawyer, but if there’s no evidence the seller was aware of a problem, they can’t be held liable. “Buyers can be stuck with tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars in repair costs,” he says.

RELATED: Trying to lie to your insurance company? Your car will betray you.

What, if anything, should be done to help buyers protect themselves is a matter of debate. The Trudeau government has yet to fulfill its campaign pledge of a homebuyer’s bill of rights that would include a legal right to home inspections. A spokesperson for Ahmed Hussen, the federal housing minister, says details will be announced at an unspecified later date.

Industry insiders, meanwhile, are confused by the proposal. Buyers already have the right to include inspection clauses in their offers; they’re just waiving it to improve their odds of getting houses. “Government is never going to make a home inspection mandatory,” says Helene Barton, executive director of the Home Inspectors Association BC. “That’s like mandating that you have to get your teeth cleaned twice a year.”

Meanwhile, in Hamilton, Molly and Matthew Fleming don’t have any buyer’s remorse. Yes, urgently needed fixes have dried up their dedicated savings for repairs. But their on-paper gains have made them grateful they bought when they did. Weeks after their purchase, a house similar to theirs sold one block away for $70,000 more than what they paid, which would have been well outside their budget. It was a perfect encapsulation of the warped effect of Canada’s real estate craze.

How long the dizzying ride will continue is anyone’s guess, but for now the Flemings look back on the risk they took as the price of entry: if they’d missed out on the house because they asked for an inspection, their window to own might have slammed shut. “And that,” says Molly, “would have been a way bigger regret for me.”

This article appears in print in the April 2022 issue of Maclean’s magazine with the headline, “Gambling with house money.” Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here.

This article contains affiliate links, so we may earn a small commission when you make a purchase through links on our site at no additional cost to you.