What on earth is Stephen Harper up to?

The former prime minister is back—with a new book, a consultancy and a flurry of lucrative speaking engagements. He also took his one-man show to Trump’s doorstep.

Former Prime Minister of Canada Stephen Harper speaks at the 2017 American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) policy conference in Washington, Sunday, March 26, 2017. (Jose Luis Magana/AP/CP)

Share

At the Lloydminster Exhibition’s Stockade Convention Centre, the stage’s black drapes are accented with a sash-like green curtain and a banner of logos for Reid Signs, Atlas Appraisal Services and title sponsor Fountain Tire. Canada’s former prime minister kicks off the night with a few jokes. There’s the one about a young girl who once introduced Stephen Harper by saying it’s not her job to give a boring speech; “it is to introduce the person who will.” The one about how he tried to join his father’s profession, but “I didn’t have the charisma to be an accountant.” The one in which he’s golfing in small-town Alberta, hooks the ball, and the octogenarian caddy declares he saw where the ball went, but can’t remember. (This synthesis of a joke-book classic doesn’t do justice to it, but various iterations are floating online if you’re curious.)

Earlier in the week, Harper had bounced from Mitt Romney’s political retreat in Utah to the Fox News studio in New York to an Israeli college’s $1,000-a-plate fundraiser in Toronto to a Saskatchewan-Alberta border town’s chamber of commerce dinner. You know, the circuit.

At the lectern in Lloydminster, Harper spends 23 minutes riffing on themes from his upcoming book about political “disruption”—rising populism from Trump to Brexit, how income stagnation and uncertainty led to an anti-establishment revolt, why trade is overwhelmingly good but Trump is right that some deals are bad, and why in this turbulent era direct relationships are key to seizing global business opportunities. And speaking of opportunities . . .

RELATED: Stephen Harper’s own words: ‘I was never in the job to be liked’

The speech starts as a stand-up routine, evolves into an Economist essay and concludes as promotional seminar. And what Harper is pushing is himself: “I’m also going to mention for those who may have interests abroad that Harper & Associates does maintain a number of platforms around the world that specialize in identifying good business opportunities in a number of sectors,” he says of his nascent consulting firm. He notes his Conservative government reached several overseas trade deals without public backlash—“so we can be helpful in navigating these trends.”

Harper spent his buttoned-down decade as prime minister living out a credo: When I have something to say, I’ll say it. Nearly three years after voters removed him from 24 Sussex, he finds himself with more to say, and none of the burden of power to weigh him down.

Harper faded from view after his 2015 election loss to Justin Trudeau’s Liberals—he went from Canada’s most important public figure to a silent opposition backbencher who made only the blandest valedictory address at his party’s convention. What then passed for Harper updates were sightings at a Florida airport here, a Las Vegas Shake Shack there. He quit Parliament in late 2016 to move to Calgary with his wife, Laureen, and start his business, but now his private life is increasingly coming into public view. Along with having something to say, Harper also has something to sell.

There’s an upcoming book—Right Here, Right Now: Politics and Leadership in the Age of Disruption—and speaking engagements, as well as his consultancy. Harper’s office is characteristically tight-lipped on his projects, but Maclean’s has learned it may include a massive Jordanian oil project, as well as courting would-be Chinese purchasers of a Canadian power producer, an interesting venture for a former prime minister who once viewed takeovers by state-owned companies with a wary eye.

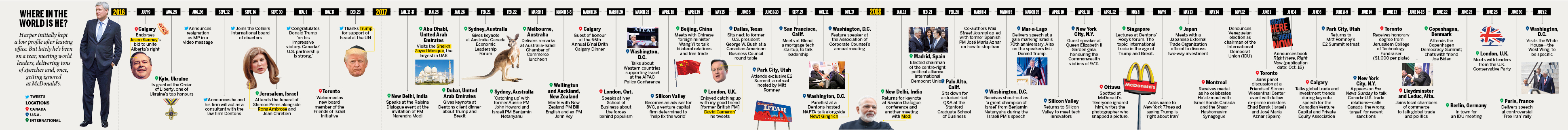

Where in the world is Stephen Harper?: A timeline of his escapades

Harper’s travel itinerary may be more loaded than it was when he was prime minister, but he’s liberated from the deluge of action items, urgent priorities and top-of-question-period news stories that used to dominate his days. He controls his pace, with time to kick back this spring at the World Curling Championships in Las Vegas, and is more easygoing at the office, too. When one aide was slow with some client correspondence, Harper quipped: “I mean, we’re not in government anymore. You can’t take forever to do nothing.”

Harper declined requests for interviews. Instead, Maclean’s spoke with current and former associates, parsed his increasingly frequent speeches and attended two closed-to-media appearances in Lloydminster and Leduc, Alta., to pull together a comprehensive portrait of Stephen Harper’s life after the prime ministership—and the shadow he might cast on politics at home and abroad.

Before watching his government fall in the 2015 election, Harper made a promise to his wife: “I would not spend the rest of my life trying to regain past glory, or settle scores or build a legacy,” he told an audience in late 2016. Nor did he want to slow into the traditional post-political life of corporate board appointments “because I think I’m too young and energetic to do just that.”

Harper stepped down as PM at 56, younger than predecessors Jean Chrétien and Paul Martin when they started in the job. He resigned his Calgary seat in late August 2016 and quickly launched what one source said Harper calls his “third career”—following his third-party advocacy and early Reform days (career No. 1) and his leadership of the Conservatives and Canada (career No. 2). Within weeks, he opened Harper & Associates Consulting Inc. with a clutch of former Prime Minister’s Office aides, a staff now numbering at least six; signed on with the Virginia-based Worldwide Speakers Group; was named to the board of Colliers International, a Toronto-based global commercial property heavyweight; and announced his consultancy’s “strategic affiliation” with multinational law firm Dentons. That’s a markedly distinct move—many ex-politicians, like former B.C. premier Christy Clark and former federal ministers John Baird and James Moore, have moved to law firms as staff senior advisers. An affiliation is better suited to the control-loving former leader—Harper and staff have office space in the Dentons Calgary office, but he’s freer to pick and choose work. (Harper has told audiences that there are some countries where he won’t do business, including Russia and Iran, whose authoritarian regimes he deplored as PM.)

RELATED: It’s NAFTA crunch-time, so why are we talking about Stephen Harper?

Harper’s third career appears to feature a few key ambitions, including money. “Compared to what I’m paid now, the job comes with fairly low pay,” he told a crowd in Leduc when asked about advice for would-be politicians.

Corporate records show his Colliers directorship brought him about $191,000 last year in fees and options, more than half his $334,800 salary for chairing the government of Canada. Harper’s speaking engagements—listed by a speakers’ agency at more than US$50,000 per appearance—have taken him from a policy talk in New Delhi to a mortgage professionals’ conference in Niagara Falls, Ont., to a fundraiser at Mar-a-Lago.

For a sign of Harper’s newfound success in business, look to the foothills southwest of Calgary and the picturesque community called Bragg Creek, Alta. There, the Harpers are building a new home on a wooded two-acre lot they purchased in 2012, when he was still in government. The massive foundation dug recently indicates a big step up from the two-storey home they’ve long owned in Calgary’s northwest suburbs—as does the $1.6-million mortgage the Harpers took out on the lot this spring, according to publicly available property records.

His interest in money-making extends beyond the personal. Besides being the Conservative party’s elder statesman, occasional adviser and patron saint of strong, stable majorities, Harper retains a formal party fundraising role, sitting on the eight-member board of the Conservative Fund Canada. In 2018’s first quarter, the Conservatives raised $6 million, more than the Liberals and NDP combined. The party sent out a fundraising email in his name in late June, touting a Quebec by-election win. “This shows that we are making great strides towards 2019 and securing a strong, stable, Conservative majority led by Andrew Scheer,” Harper writes in the email. “I want to ensure that we keep pressing in the right direction.” In a follow-up email the next day, Conservatives proclaimed that donors hit Harper’s $50,000 target within nine hours.

At a talk Harper held at Stanford University in February—a heavily Canadian crowd turned up—he discussed how he wanted the Conservative party to endure after him. He got improvisational in his explanation: “I could have turned the party into essentially a personal political vehicle if I’d wanted,” he told the audience, “but that was not my goal.” (As he’s learned bitterly from experience, his off-the-cuff speaking can land him in hot water—witness his 2008 remarks that the stock-market crash brought “great buying opportunities.”) His awkward words at Stanford made headlines when they became public months later, setting off a string of Harper vs. Scheer articles, as well as accusations from Harper’s camp that his words had been torqued well beyond context. “Such a disservice to the nuanced, experienced perspective actually expressed,” tweeted Rachel Curran, a former Harper policy aide now with his consulting firm. The Liberals revelled in the brouhaha, fundraising off the suggestion that “It may be Andrew Scheer’s smile, but it’s still Stephen Harper’s party.”

Harper tells crowds he doesn’t want to comment on the new government, and that he doesn’t know a former world leader who thinks his successor is doing a good job. And yet: “I think it is frankly disgraceful and unforgivable that we have a federal government that thinks it can be against key industries in the western Canadian economy,” Harper told Prairie crowds, drawing applause two nights in a row. While the Liberals would argue their purchase of the Trans Mountain pipeline project puts money behind their rhetoric on oil industry support, Harper argues they have killed past pipeline projects and have no intention of building this one, either. He also calls the carbon tax a “tax policy” rather than an environmental measure: “Let the other guys do a carbon tax, because we can all win the next federal and provincial elections on that issue alone.”

READ: Stephen Harper’s NAFTA memo shows how little the former PM has changed

Those comments don’t range too far from the post-Harper Conservative line on carbon tax and pipelines, but while Scheer has said he’ll come up with a climate plan that meets Canada’s emissions-curbing pledges under the Paris Accord, Harper mocks the global climate agreement’s voluntary targets. “I argued with members of our party last May that the Paris agreement is the most meaningless international agreement ever signed,” he said in Lloydminster.

He told the business crowd Scheer is doing a good job. “I always say with Andrew he’s a sensible, energetic, family, conservative guy,” he said. “Nothing strange or weird is going to happen with Andrew. His feet are on the ground.” The following night in Leduc, he gave far more glowing praise to former lieutenant Jason Kenney, the man he’s confident will become Alberta premier: “It is not just that Jason Kenney performed well in every job I gave him. It’s that he got better and better and better at every one.” And as for Ontario’s new premier, Harper doesn’t put the populist label that many do on Doug Ford. “Rob [Ford, Doug’s brother and former Toronto mayor] was a great guy, but Rob was genuinely a wild guy. Doug is not a wild guy. He is a businessman. He’s got very sensible conservative instincts.”

He defends Canada in the NAFTA battle, but he’s doing it on his own terms rather than linking up with the government’s multi-partisan Team Canada as some provincial conservative leaders and former federal ministers have. A recent Fox News interview was largely well-received at home for calmly criticizing Trump’s trade actions against Canada the day after the president’s G7 explosion—“I don’t think even Trump supporters think the Canadian trade relationship is a problem,” Harper said. But he also shaded outside Ottawa’s current message lines. He’s more sympathetic to Trump’s grievances about Chinese trade deficits and Mexico’s auto manufacturing: “I’d be the first person telling our government to be a partner in these things because Canada shares those concerns,” he told the Trump-friendly U.S. station. In a memo to consultancy clients obtained last fall by the Canadian Press, Harper criticized Trudeau for negotiating with Mexico on NAFTA and pursuing his own goals on gender and the environment. He went further in Lloydminster, saying that while there was no alternative to Canadian counter-tariffs, “you don’t get into these kinds of conflicts if you’re showing you’re valuable.” He suggested Canada should thank Trump for approving the Keystone XL pipeline, recognizing Jerusalem as Israel’s capital and backing withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal.

Right Here, Right Now, Stephen Harper’s book for international politicos and business leaders, comes out on Oct. 16. That’s in the thick of Parliament’s fall session, just shy of the third anniversary of his electoral defeat, a year before the next election and a week ahead of My Stories, My Times, the latest anecdote-laden memoir by fellow ex-PM (and Dentons colleague, incidentally) Jean Chrétien. Judging by the previews he gave small-town Prairie business groups in June, Harper’s volume will be thick with pragmatic incrementalism and empathy for populist voters, thin on tell-all and—based on your perspective—liberally or conservatively speckled with self-congratulations for Harper’s performance in office. Whether you’re in Harper’s old party or on the side derisively calling it “Harper’s party,” both camps will have reason to closely scrutinize what he has to say.

“I think he knows with some satisfaction that even his critics are going to read that book line upon line, precept on precept, looking for something,” says Stockwell Day, a former trade minister for Harper.

Andrew MacDougall, a former Harper aide now based in London, believes the former leader is keener on what foreign audiences think of his third career’s advocacy than how Canadians parse it. “I think he, quite frankly, couldn’t give a shit what people in Canada think,” MacDougall says. “He’s not speaking to that audience; doesn’t look like it to me.”

As somebody who entered politics through Canada’s mildly populist Reform movement then erected its new Conservative establishment, Harper isn’t among the former world leaders casting this populism moment in a grim light.

“Many of these populist movements are right in their assessments of the problem,” he told the Leduc crowd. “And as conservatives—the book is obviously written from a conservative perspective—and for those who are business leaders or even other political parties, we should stop attacking these people and instead recognize that they have legitimate concerns and adapt our models and our good conservative values to address these concerns.”

Criticize the anti-globalization right-wingers if you want, but “a lot worse awaits us,” Harper warned the audience. “Donald Trump and the Brexiteers are unorthodox political movements that are trying to fix democratic capitalist systems. The people who would come after them if they fail, the Jeremy Corbyns and the Bernie Sanders, are people who want to destroy democratic capitalist systems.” One fan in Leduc, a few rows from the stage, proclaimed: “Amen.”

A week later, at the Copenhagen Democracy Summit, which brought together former leaders from Europe and North America, former U.S. vice-president Joe Biden denounced the “demagogues and charlatans” who prey on disaffected voters. Harper urged viewing the Eurosceptics and nationalists who win not as threats to democracy but outcomes of the system. “If we just try to delegitimize all unconventional choices as anti-democratic then I think we are going to go down equally dangerous ground.”

As much as Harper remains on Team Democracy and Team Trade, he’s sticking with Team Conservative—in fact, he’s become its global captain. In February, he became chairman of the International Democrat Union, the league of right-of-centre parties founded in the era of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan. Here, too, Harper told the Toronto Sun, he wants to ensure that “we address the concerns of frustrated conservatives and that they do not drift to extreme options.” One of his visible duties atop this fairly low-profile organization is to publicly congratulate member parties on election wins—even if that did mean Harper tweeted praise to Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban “for winning a decisive fourth term!” This, despite critics widely decrying Orban’s “illiberal democracy” approach, weakening of civil institutions and anti-migrant stance. Harper’s own speeches, meanwhile, lump Orban in with populist European leaders such as Italy’s and Poland’s, as well as Mexico’s Andrés Manuel López Obrador, the new president from the left.

He’ll poke gentle fun at Trump, kicking off sections of his speech by citing the U.S. president’s favourite line: “What the hell is going on?” But Harper must also show so much deference to and understanding of the America First-ism that he adds qualifiers like: “This is not to say that all of Donald Trump’s trade actions are justified, or even that they all make sense.”

READ: Why Stephen Harper congratulating Viktor Orbán matters

He doesn’t think it’s useful to join the throngs calling Trump a maniac, but he does sincerely want to do what he can to stop a slide to all-out trade wars and mercantilism, says MacDougall. “He’s doing this because these are things he believes in, and it’s an important time now for the world,” he says.

The intersection of populism and trade may be Harper’s second-favourite subject on the speaking circuit, after Israel. His sharpest post-political advocacy is for the Jewish state, after steadfast rhetorical support during his time in government. Maclean’s counts at least 10 Israel-related speaking engagements or events Harper has attended since leaving office, including three in June—plus a private event at the mansion of pro-Israel casino magnate Sheldon Adelson for the Republican Jewish Coalition while still an MP in 2016. Harper has become a director of the Friends of Israel Initiative, a group of former political leaders—and it was through that group that he co-signed a full-page ad in the New York Times praising Trump’s pulling out of the Iran nuclear accord, which Israel hotly advocated but Canada’s current government didn’t.

“He’s a man of principles and he’s not going to let political exigencies affect his standing for what he believes is right, even if not popular,” says Rabbi Yechiel Eckstein, head of the International Fellowship of Christians and Jews.

When that charity held its first gala, at Trump’s glitzy Mar-a-Lago resort in Florida, it hoped to book Nikki Haley, Trump’s U.N. ambassador, Eckstein recalls. When she was unavailable, his board (whose chairman is Stockwell Day) opted for Harper.

According to a speech transcript provided by the charity, Harper started with the same golfing and accountancy jokes, then ripped into anti-Semitism on campuses, Iran’s threat to Israel, how he would declare Jerusalem the state’s capital if he were prime minister, and why unequivocal support of Israel is “plainly and simply the right thing to do.”

When Harper attended an annual gathering of the American Israel Public Affairs Committee in Washington this spring, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu told him from the stage: “Stephen, we never forget our friends. And you are a tremendous friend, and still are.”

Harper’s consultancy work, meanwhile, has involved one of Israel’s friendlier neighbours in the Arab world: Jordan, with which Harper signed a free-trade deal while prime minister. He’s working for Calgary-based Questerre Energy, which wants to negotiate a mining lease on a massive swath of Jordanian oil shale, for which it currently has exploratory rights.

While there are restrictions on former Canadian ministers and senior aides lobbying the government (Harper’s own government enacted a five-year lobbying ban)—no such restrictions exist for Canadian leaders representing companies to foreign governments abroad. It’s unclear if Harper & Associates has been speaking directly to Jordanian officials about Questerre’s oil plans. “Strategic advice on how to position ourselves to minimize our political risk—that’s what we hired him for,” CEO Michael Binnion says. “Does he have a lot of contacts? Of course.”

Questerre is better known in Canada for its bid to frack for natural gas in Quebec, an activity the province has tightly restricted. In his western business speeches, Harper touted an industry-commissioned poll that suggested Quebecers support more energy development—research he’d heard about at Questerre’s annual meeting, Binnion says. “Do I want to say that I’ve never asked Stephen Harper: ‘Hey, what do you think about this in Quebec?’ or, ‘We’ve got a Montney [natural gas] play in Alberta, what do you think about the NDP government?’ I may have done that.”

For his part, Harper has remained mum on his business. In an email, Harper spokesperson Anna Tomala answered a wide range of questions about Harper’s consulting thusly: “Harper & Associates does not confirm or comment on its clientele or its business operations.” The firm helps Canadian firms do business abroad but does much work with global firms eyeing Canada, says Ken Boessenkool, a former Harper strategist. “He helps them understand Canada and then they take it from there,” he says.

Allies say Harper strives to do deals that won’t conflict with his values or cause him reputational harm. Cautionary tales abound: Britain’s Tony Blair controversially made millions advising Kazakhstan’s dictator and other questionable governments; some European politicians want sanctions against former German chancellor Gerhard Schröder for his lobbying for Russia’s Vladimir Putin; and Harper knows well the tale of Brian Mulroney and arms dealer Karlheinz Schreiber.

“Sometimes people see economic advantage in saddling up to countries or causes where money can be made. That’s not who he is,” former finance minister Joe Oliver says of Harper. “He’s not going to sell his soul for a mess of pottage.”

In addition to swearing off dealings with Russia or Iran (Harper was recently criticized for speaking at an event sponsored by MEK, an Iranian dissident group once considered a terrorist group by the Canadian government), a source says Harper also approaches work in China cautiously, as he did as prime minister. In public speeches, he has criticized China as a threat to the global democratic order, and in Copenhagen he suggested Xi Jinping’s authoritarian regime may end in “stagnation, tyranny or both.”

In late 2016, in the consultancy’s early days, Harper & Associates appeared in Chinese-language ads declaring that Toronto-based Northland Power, a $4-billion natural gas, wind and solar power producer, was seeking a buyer. The ad stated that Harper’s consultancy and investment bank Origin Merchant Partners was assisting Northland, and interested parties were urged to contact Ray Novak, Harper’s former chief of staff and his firm’s managing director.

Northland, with electricity operations in Canada and overseas, was indeed seeking a buyer at the time—but took itself off the market less than a year later, after Bloomberg reported that two Chinese state-owned firms placed initial bids and then balked for different reasons. Oliver, who at the time chaired the bank’s advisory board, confirmed he linked Origin and Harper’s firm for this venture. But any discussions with interested Chinese buyers would only have been cursory and exploratory; Harper’s spokesperson said the consultancy was never retained by either Origin or Northland, and Northland stated it has never engaged Harper’s firm, and only had introductory discussions about involving Origin in its bid to find a buyer.

READ: Inside Stephen Harper’s efforts to extend Canada’s Afghanistan mission

Had a deal been struck, such a large foreign takeover by a state-controlled entity would automatically have triggered a federal review, and may have required national security scrutiny as a piece of critical infrastructure—putting the final decision in the hands of the cabinet of Harper’s successor. While in office, Harper approved a $15.1-billion state-owned company’s purchase of oil giant Nexen and set up strict guidelines on such deals afterwards. Trudeau’s government later rejected a Chinese takeover of construction firm Aecon, invoking national security concerns related to the company’s infrastructure projects.

Any questions raised by these glimpses into Harper’s consultancy business will go unanswered. He disliked responding to such scrutiny while in office, and his post-politics career is also largely post-accountability.

With his book and public advocacy, Harper will garner attention from both sides of the political aisle at home and abroad, where his comments are parsed more generously and his legacy less checkered. He can address the issues he wants and ignore the rest, and if the media picks apart (and in his view misrepresents) his points, plus ça change. The more he has to say, the more he influences rhetoric from Scheer and Trudeau, the more the drama consumes Harper’s critics and galvanizes his fans—and the longer it takes Canada’s political discourse to move beyond the Harper decade.

Word of a planned trip to Washington in early July to meet with White House economic adviser Larry Kudlow (U.S. national security adviser John Bolton—who until recently worked alongside Harper on the Friends of Israel board—was also a rumoured meeting, but reports say it did not come to pass) caught the Canadian embassy in Washington by surprise. Embassy sources told the CBC they were called by Bolton to make arrangements for the meetings, which Harper, they said, had requested. Since leaving office, he’s also met with Netanyahu, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Britain’s home secretary and even the Aga Khan, the religious leader Justin Trudeau has controversially become chummy with.

The Prime Minister’s Office has not commented. Nor has Harper’s spokesperson. The White House confirmed the meeting took place but declined comment on both the agenda and any imagined outcome.

As he left his secret meeting with Kudlow, an Associated Press photographer captured a fleeting image of Harper taking leave of the West Wing.

He is head-down, walking determinedly, avoiding the press. But look closely. It’s also quite possible he is smiling.

—With files from Céline von Engelhardt and Emily Senger