How Doug Ford did it

Inside the chaotic Ontario election campaign and the last-ditch effort that put the controversial PC leader in the premier’s office

Ontario PC leader Doug Ford reacts with his family after winning the Ontario provincial election on Thursday, June 7, 2018. (Nathan Denette/CP)

Share

It’s an enduring quirk of politics that when you see a politician’s face on your TV or computer screen, it’s likely one of his opponents who put him there. Doug Ford had been the leader of the Progressive Conservative Party of Ontario for all of a month and two days when somebody decided it was time to introduce him to Ontario voters. Of course the somebody was the Liberals.

It was April 13, almost four weeks before the official start of the brief campaign. “There’s the Doug Ford you think you know,” a female voice-over in one ad said over a photo of Ford already not looking great.

“And then there’s the real Doug Ford—who’ll give corporations huge tax cuts but take the minimum-wage raise right out of hardworking people’s pockets.” Shot of a sunrise over soulless office towers, shot of a regular guy looking glum.

The voice-over wasn’t done talking about Ford, “who’ll fire 40,000 people, including teachers”—image of a female schoolteacher—“and nurses”—image of nurses hard at work. “Put restrictions on a woman’s right to decide her own pregnancy.” Young woman in a hoodie on a sidewalk, brow furrowed. “And won’t make big business pay a cent to address climate change.” Smokestacks belching enough smoke to launch a space shuttle.

“The real Doug Ford,” the woman said. “He’d be comfortable living in that kind of Ontario. Would you?” The ad’s ominous music ends with a division bell reminiscent of a boxing match. Game on.

READ MORE: ‘My friends, help is here.’ Doug Ford wins a majority in Ontario.

Every element of the ad was an homage to the campaign craftsman’s art. Teachers and nurses have unions that can be mobilized by threats to their livelihoods into armies of campaign support. The numbers didn’t come from Ford—he kept swearing he’d never lay off a single person if he became premier—but they didn’t come from nowhere, either: economist Mike Moffatt had come up with the estimate of 40,000 public-sector layoffs. As Stephen Harper, a dab hand at defining his opponents in his day, liked to tell his staff, an ad wouldn’t work if it didn’t at least feel like the truth.

Tellingly, and unlike some of the greatest hits of the Harper years, this Liberal ad didn’t make any pronouncement at all about Ford’s personality, his appearance, the way he walked or talked. It was uniquely an argument about the purported effect of his policies. The Liberals’ research had told them that voters, already yearning for a change after 15 years of Liberal rule, would cut them very little slack in their campaign. Anything that smacked of a personal attack against an opponent, even Ford, any hint of cheap mockery, would rebound. So the ad was a set of claims about what Ford would wreak, not about what he was like.

Most important, except for one glum laid-off guy, almost every human element in the ad—the voice, the teacher, the nurses, the worried woman wondering about her abortion—was a woman. “They really only have one play,” a veteran federal Liberal had said of his provincial counterparts a week before the ads appeared. “That’s gender. Women don’t feel comfortable with Ford. The Liberals need to drive up that gender difference.”

It’s always hard to tell how much a party has invested in an ad, not just in money but in effort and hope. They’re so cheap to make nowadays that sometimes a party just slaps one up on its own website and calls it a day. But this ad was old-school. The Liberals told reporters they were spending $1 million on it, and they made sure it played during TV shows people watched. They put it on Facebook and Youtube and all the odd places people pay more attention to these days than television.

And it worked a charm, sort of. “It drove up Ford’s negatives, it shrunk his voter pool”—the number of Ontarians who would consider voting PC, even if only as a second choice—“and it drove about 8 points of PC support straight to the NDP,” David Herle, the veteran strategist who served as Liberal campaign co-chair, said in an interview.

Come again? It drove Ford’s support to the NDP? But it was a Liberal ad.

Perhaps, but Herle and other Liberals from the Wynne campaign maintain that those ads were spectacularly effective at driving down Ford’s support, but that the Liberals saw none of the benefit. Voters who were spooked at the Liberal vision of a Ford future just moved their support to the NDP. And not only voters who’d been planning to vote Conservative. “We shed about 8 points to the NDP too,” Herle said.

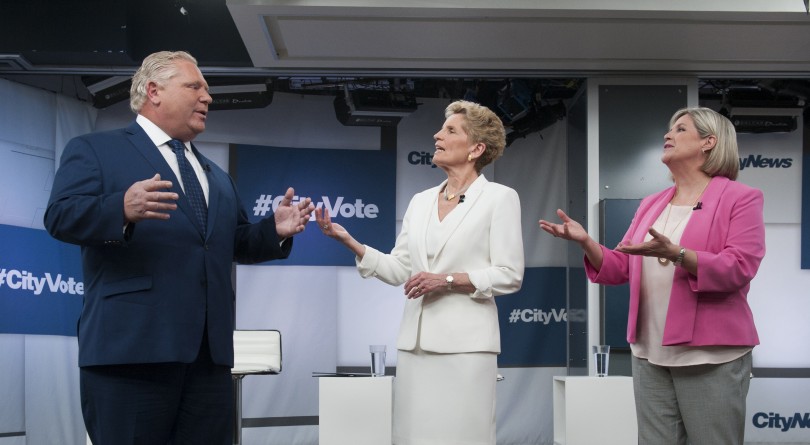

The Liberals may be flattering themselves when they attribute every bit of the pre-campaign movement in public opinion to their ads. There was a lot going on. The first televised leaders’ debate, on City, was on Monday, May 7. The official campaign launch was May 9. Voters who’ve tuned out of provincial politics tend to tune back in, in dribs and drabs, as voting day approaches, and maybe some of the shift would have happened anyway, without the Liberals painting Doug Ford against electronic storm clouds.

But a Pollara poll for Maclean’s, published on the day of the City debate, May 7, showed support for Ford’s PCs at 40 per cent, to 30 per cent for Horwath’s NDP and 23 per cent for the Liberals. That’s within a point of the support voters handed the PCs exactly a month later, barely three points below Horwath’s final support, and about four points high for the Liberals.

In a turbulent campaign, what stands out in hindsight is how little the numbers moved.

“You could actually make an argument that the campaign didn’t matter,” Herle said. “I thought we’d get him [Ford] down to 30 per cent. But we took our foot off his throat because we were driving votes to the NDP. And nobody ever went back at him.”

It may not quite be that the campaign didn’t matter so much as that very little that happened in the campaign could compete with the turmoil before it. For two years before 2018, the Liberals under Wynne were becoming steadily less popular. The NDP under Andrea Horwath was all but ignored in political coverage. And the PCs, under a wiry runner from Barrie named Patrick Brown, were slowly setting themselves up to be an alternative to the Liberals.

Brown had been an unnoticed back-bench MP in Ottawa for most of the time Stephen Harper was prime minister. His entry into the Ontario race to succeed Tim Hudak, a diligent student of politics who just couldn’t connect with voters, seemed at first to be of only anecdotal interest. But Brown had been assigned a bit part in the Harper Conservatives’ ethnic outreach strategies while in Ottawa, and he took that same attitude to provincial politics, attracting voters of South Asian origin in particular.

Next he set about building an election platform that was surprisingly centrist in orientation, going so far as to accept a federal carbon tax to fight climate change—along with the substantial revenues that would come with such a scheme.

Brown’s analysis was that the PCs had lost elections in 2007, 2011 and 2014—despite growing discontent with the Liberals—because some element of their platform had always seemed too extreme to voters. Back when the Conservatives used to win elections in Ontario, after all, they did it under amazingly boring centrist leaders like Bill Davis. Brown’s willingness to accept a carbon tax was a totem of his eagerness to play in the same turf.

A few PCs hated the idea, but anyone who objected too vociferously, or who wanted to spend too much time talking about social issues like abortion or immigration, was ruthlessly sidelined under Brown. That created a lot of pent-up resentment in the party, but it also allowed Brown to attract interesting candidates of the sort who normally only enter politics when they sense a cabinet post might be their reward: the lawyer Caroline Mulroney, member of one of Canada’s political royal family, and the Toronto businessman Rod Phillips, for starters.

Then, of course, on Jan. 24 news broke of allegations of sexual assault against Brown. He resigned as Conservative leader before the night was through. The Conservatives had to pick another leader in just a few weeks. One by one the candidates disavowed the carbon-tax plank that had been the source of billions of dollars of revenue in Brown’s platform. Less spectacularly, the party threatened to tear itself apart from within, as supporters and detractors of Brown fought for control over the nomination process and the party hierarchy.

When Ford became the leader on March 10, his peculiarities—he took a spectacular disinterest in the details of government, and as the brother of the late Toronto mayor Rob Ford, he came from one of the most infamously dysfunctional political families on Earth—were a problem. But perhaps an even bigger problem was that he had only three months to prepare and execute a campaign for premier.

READ MORE: The triumph of Doug Ford

His campaign brain trust was not seamless. Dean French, a former federal Conservative with Canadian Alliance roots, became campaign chair. Chris Froggatt, a former chief of staff to John Baird in Ottawa, now a principal at National Public relations, was vice-chair. Kory Teneycke became campaign manager. He had served as a spokesman for Stephen Harper and had been the guiding force behind the sensational, short-lived right-wing Sun News TV channel. Teneycke brought in Jenni Byrne, an old friend who had run Harper’s campaigns in 2011 (a triumph) and 2015 (a disaster).

This crew didn’t agree on much, and they didn’t have the fine-tuned machinery or the rehearsal time that would have permitted them to run a complex campaign. Fortunately they had no intention of doing any such thing. Teneycke’s guiding philosophy was that everybody else would try to make Ford a target, so the campaign should contribute as little as possible to that effort. They would come as close as they could to running a leaderless campaign.

Ford would travel alone. There would be no mechanism for reporters to travel with him. If they showed up at his events—and not all of his events were public—they often found they couldn’t ask questions, and if they could, they were cut off after fewer than half a dozen, most days. Ford kept promising a full platform with a proper accounting of the costs of his promises, but Teneycke was adamantly against it: a platform was just a list of things your opponents could criticize. In the end there would be no costed platform.

What Ford did promise was fiscal nonsense—a succession of tax cuts with no specific offsetting spending cuts—but it was the sort of thing that you might notice if you didn’t normally pay much attention to politics. Beer for a dollar a bottle. A 10-cent cut in gas taxes. Both actually difficult to deliver, but hard to miss when they came up. And if the swells in the press gallery howled that a gas tax cut was exactly the opposite of what Ontario needed in its fight against climate change, well, that was a feature, not a bug.

As for Horwath, her campaign was defined by the need to avoid serious trouble she’d run into in 2014, her second campaign as NDP leader. She made the mistake New Democrats were making those days—Tom Mulcair would do basically the same thing when he ran for prime minister in 2015, and Olivia Chow when she ran for Toronto mayor—and offered the blandest, most ostentatiously respectable platform she could stand.

What she got for her pains was a demoralized, uninterested voter base and a snotty letter to her from more than two dozen NDP backseat drivers, complaining that she seemed to be running to Wynne’s right, which magically got leaked to the newspapers. NDP support didn’t improve in that campaign, and Horwath was lucky to survive a leadership review soon after. She spent the ensuing four years building a platform the party would enjoy watching her defend.

“Our goal was to be in second place by mid-campaign,” an NDP campaign source told Maclean’s. They reached that goal before the campaign even started. Horwath on the May 7 City debate was ebullient, cheerful—barely able to believe her luck. It helped her charm a few voters who hadn’t yet decided whether she could be a credible vessel into which to pour anti-Ford sentiment, and it sunk Wynne a little further.

Another effect: “From Day One, right out of the gate, the Liberals were attacking us,” the NDP source said.

It was, in many ways, a curious campaign. The three leaders hardly seemed to be applying for the same job. Wynne’s campaign was classic, elegant in its visuals, gracious in manner, elaborate in its logistics. Every Liberal I spoke to for this article was proud of their team’s effort in presenting a leader they admired in the best possible light. Everyone is cruelly aware it did them basically no good as the party cruised to its worst result since Confederation.

The Conservatives played a double game with their leader, conscious that he—and the associations with his late brother—were among their best assets among core Conservative voters, but that Doug Ford also carried a built-in ceiling that limited his ability to appeal outside the Conservative base. They needed to show enough of him to rally the rural base, while limiting his exposure to harsh questions from a basically antagonistic press corps. It mostly worked. At one point, the Liberals’ Herle says with wonder, the Conservatives were receiving 62 per cent support among rural Ontario men.

The NDP knew that their best asset was Horwath, whose positive perception was much higher than her party’s. To some extent, they over-relied on her. They could have picked up the baton from the Liberals and run harder ads against Ford, but the frame of the NDP campaign was that the other parties fought while New Democrats proposed solutions. So they couldn’t really join the fight, or thought they couldn’t.

Sorry, that bit about New Democrats proposing solutions wasn’t quite right. In the semiotics of the NDP campaign, it’s not New Democrats who propose solutions. It’s Andrea Horwath. She polled ahead of her party. So her party did its best to hide itself from view.

In the campaign’s home stretch, in a bid to bolster the PC vote in urban ridings that might view him with suspicion, Ford finally started showing up with prominent candidates—implying, without promising, that they’d be part of his government. Rod Phillips. Caroline Mulroney. Christine Elliott, Ford’s erstwhile leadership rival.

Horwath appeared in no such staged tableau of NDP luminaries. But the front page of the Toronto Sun, at times indistinguishable from communiqués from the Conservative campaign, kept showing NDP candidates who had made outrageous statements or otherwise shown poor judgment.

Right-leaning or centrist personalities who decided to back Ford were made stars for a day by the Conservative campaign: the former Toronto mayor Mel Lastman, the longtime former Mississauga mayor Hazel McCallion. If anyone outside the NDP thought it might be a good idea to have Horwath as premier, the NDP was in no hurry to let you know about it.

These base-broadening exercises—team-building, tent-building—aren’t the heart of a modern campaign, but they signal a party that’s building from opposition to, at least potentially, prepare to govern. The NDP’s rivals were amazed that they didn’t do any of this. “I mean this in the nicest way,” one Conservative familiar with the Ford campaign said, “but the NDP—they’re born losers. It’s like they never decide that they actually want to win something.”

Horwath can content herself with one of the party’s best showings ever, outside the fluke Bob Rae NDP victory of 1990. She has nearly doubled her party’s representation in the legislature, and she can now set about recruiting a candidate slate that will be readier for prime time next time.

The Liberals are in long-term trouble. Trouble isn’t necessarily fatal. The federal Liberals had a terrible decade before Justin Trudeau became their leader. But it’s still trouble. It’s not just that Wynne’s party won only 7 ridings. On a quick rough count based on preliminary returns, the Liberals came second in only 28 ridings—and in all except one of those, the Liberal was an incumbent, which normally means they should have been expected to have done reasonably well. In 85 ridings, the third-place candidate was the Liberal, including 35 ridings where the Liberal incumbent fell to third. So in most of Ontario, the Liberal did not merely lose the riding, they no longer have enough of a hold on the electorate to be readily competitive next time.

For the Liberals, there’s a mix of resignation and amazement. Resignation because after a decade and a half in power, maybe your number comes up and you can’t do much about it. “I think that’s true of every 15-year-old government,” another senior provincial Liberal said. “I don’t think there’ll be a lot of 15-year-old governments”—of any stripe—“for a while.”

Amazement because Wynne’s own campaign staff, at least, would gladly walk into traffic for her. Should she have quit earlier? No, Herle maintains, because the measures she introduced near the end of her time in office—a higher minimum wage, serious assistance for university tuition, elements of pharmacare and child care—were worth doing, in his eyes. But also because “at no point did I hear about anyone—at no point did anyone suggest to me—that there was somebody in the caucus who could do better.”

But that fondness and loyalty for Wynne went nowhere with voters. “The resistance to the premier was unlike anything I’ve ever seen in politics before,” Herle said. It wasn’t there when Wynne was still a new leader in 2014, but it set in.

One indication: Dalton McGuinty cancelled contracts to build gas plants in 2011, a sop to some ridings the Liberals thought they could win. The cost of those cancellations eventually topped $1 billion, and the gas plants became a symbol of Liberal willingness to do anything to win. But that was in 2011. Wynne ran and won in 2014. And in 2018, “we heard more about the gas plants in focus groups in this campaign than we did in 2014.”

And Ford? A lot of the coverage centred on his refusal to release a fully costed platform, or to tow reporters along with him to his events. “I don’t think it hurt them,” Herle said, in remarks that are likely to be ignored by Ford’s critics as he settles into power. “I think a lot of these institutions that those of us who are involved in things—these conventions or norms that we value—are much less valued by the general public.

“I think that at the core of his vote is an extremely angry group of people who feel victimized by change. And feel that their relative status in the world has been declining. Whether it’s compared to people of other backgrounds, people of other genders. They feel that they’re relative losers from change and they’re angry about it. And they don’t care. Whether it’s Trump or Ford. When the mainstream media says, ‘Hey, these guys are gonna burn the house down,’ they don’t care. They hate the house.”

It’s why the Liberals, in ads that helped define the campaign both for themselves and for Ford, concentrated on his policies, or at least a combative but defensible interpretation of his policies, rather than on his personality or his brother or his family.

“The more of a circus the campaign became, and the more it was about the Ford circus, the better off he was,” Herle said. “Because the focus was off of what he would do to ordinary voters and it became about whether the elite thought he was an appropriate person. And that was his strongest ground.”

MORE ABOUT 2018 ONTARIO ELECTION:

- Ontario election 2018: Four decades of voter turnout in one chart

- Kathleen Wynne speaks following the Liberals’ crushing election loss – Full video

- The existential crisis of Doug Ford: What does a modern conservative government look like?

- Doug Ford, Ontario’s next premier, holds his first post-election press conference — Full Video