Economic uncertainty in Canada is rising—and it’s partly our own fault

Opinion: Outside forces are roiling Canada’s economy—but our politicians aren’t helping either, as they bluster, preen, and make our domestic future harder to predict

Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau speaks during a news conference at the Canadian Consulate General in New York City on May 17, 2018. (Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

Share

Trevor Tombe is an associate professor of economics at the University of Calgary, and aa research fellow at the School of Public Policy.

These days, news flows through a firehose.

Take a moment to reflect on the past month alone. U.S. President Donald Trump levied new tariffs on steel and aluminum, and Canada, Mexico, Japan, the Europeans, and many others will retaliate. The President also levied new tariffs on $50 billion of imports from China; they too will respond. The G7 meeting in Quebec ended with Trump attacking Canada’s dairy policies and threatening new tariffs on autos. Meanwhile, Italy may veto the Canada-EU free trade deal. Japan banned Alberta wheat. And Mexico may soon elect a new government that could further complicate NAFTA talks.

But here at home, domestic policies are also in flux. Alberta and B.C. were at the brink of a trade war. The federal government bought the Trans-Mountain pipeline. There’s a new government in Ontario that announced it will immediately end the province’s cap-and-trade system, but was silent on many key details. And many longer-term challenges—like Alberta’s large and persistent budget deficit—remain unresolved.

These are increasingly uncertain times. And we might be making it worse.

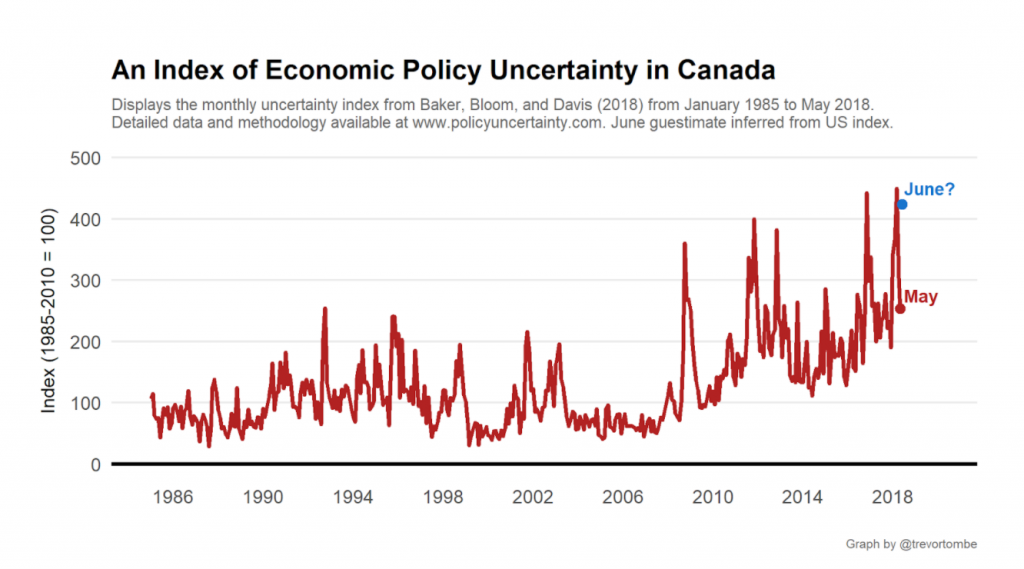

First, some data. Economists Nicholas Bloom of Stanford, Scott Baker of Northwestern, and Steven Davis of Chicago constructed a novel measure of economic uncertainty in many countries. Based on real-time, detailed analysis of the content of news in major outlets, they found that uncertainty in Canada is higher and more volatile than ever.

Data for June is not yet available, but we can expect a significant increase. Daily measures for the United States show just that. I plot (in blue) what June might be if our index rises as much as theirs has so far.

This matters. Research consistently links increased uncertainty to decreased business investment, output, and employment. Firms may even become overly cautious in responding to typical price signals.

Of course, some of this is beyond our immediate control. The financial crisis, the European debt crisis, Brexit, or the drop in oil prices—as Albertans know too well—are beyond our control. But uncertainty over domestic policy is an unforced error—and while Trump’s erratic anti-trade agenda is a serious threat to small and open economies like Canada’s, we’re adding to the uncertainty ourselves.

Sometimes, it’s uncertainty from kicking tough decisions down the road. Alberta’s budget deficit, for example, is not an immediate risk to the province, but there is no clear end in sight. Rating agencies have repeatedly downgraded the quality of Alberta’s debt largely because of the lack of a clear path forward. If our leaders plan to address the province’s fiscal gap, we do not yet know how or when. This true on both sides of the political aisle.

Other times, it’s uncertainty from haphazard implementation of otherwise sensible decisions. Ontario’s premier-designate Doug Ford announced the immediate end to its cap-and-trade program. Taking that decision is one thing (and I think it’s a good idea). But announcing its immediate end before planning a smooth transition is quite another.

What happens to permits that have already been bought? Will businesses be left holding the bag? What happens to Quebec and California’s systems? Laying the groundwork for large-scale moves is hard but necessary work. Such questions are likely and rightly giving investors pause.

Federal policy uncertainty matters too. Consider the decision to include upstream and downstream emissions in pipelines evaluations. Whatever one thinks of the merits of this idea, the government did not say how it would be implemented or why it was needed. Canada’s emissions will soon be covered by broad and stringent pricing, after all. With potentially higher costs or regulatory hurdles, each of unknown magnitude, investors will sensibly think twice.

Reasonable people can disagree over the merits of free trade, climate policy, budget deficits, or pipelines. But the lack of clear planning, whether from parties in power or in opposition, undermines investor confidence.

At the very least, we should have full and frank debates and take clear and purposeful decisions. Our elected leaders rightly have electoral considerations in mind. But a focus on the short term risks creating greater costs down the road.

Carbon taxes provide the best example, and it may be the defining issue for multiple upcoming elections. Few politicians who oppose it are climate-change deniers. Almost all agree on the Paris goals. But carbon-tax opponents rarely propose any particular alternative. Instead, for many, opposing the policy is an end in itself, and productive debate is avoided.

The federal Conservatives, for example, forced a 12-hour all-night sitting of the House of Commons last week to demand that the government reveals how much carbon taxes might cost families. Fair enough—except for the small detail that many, many, many, many estimates already exist, with some cited by the government and the Senate.

This is not to say one must support carbon pricing. Not at all. The same is true for pipelines, supply management, tariffs, and so on. Whatever one’s position, be open about your objective. Ask what problem you are trying to solve and propose policies to achieve it. Critique policies you disagree with by using evidence, analysis, and alternatives. For governments, when implementing large policy changes, do so with a detailed and transparent plan, phased in gradually over time. Announcements without details can be damaging, and rapid change can be disruptive.

While it may not be easy to do, there’s value in it. An investor deciding where to bet their next dollar must consider what future policy might be, and right now, making that assessment is harder than it needs to be.

With rising global uncertainty, governments and opposition parties should strive to do better. Bluster may be easy—but it’s not free.