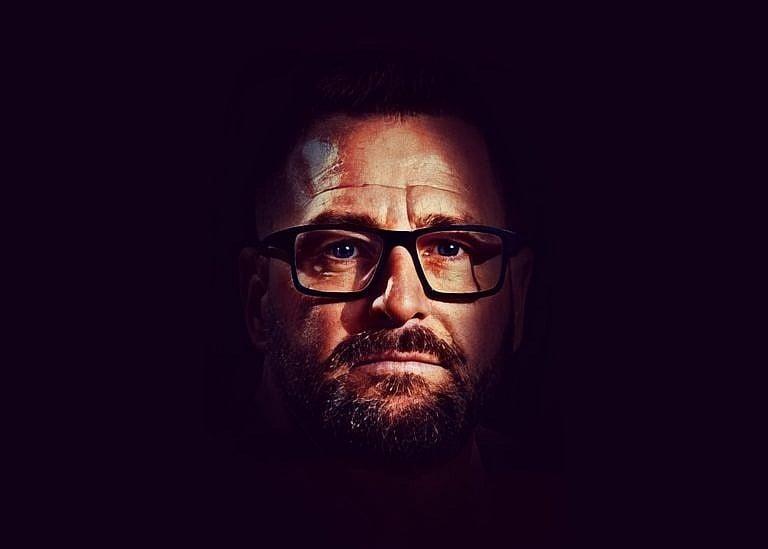

I placed my first wager when I was 10. I’ve gambled more than $1 million since.

A memoir of addiction, desperation and the dangers of sports betting

”By 2018, I owed $49,000 to my bookie and $26,000 on credit cards. We had to refinance our house to cover the debt.” (Photography by Rémi Thériault, illustration by Maclean’s.)

Share

For the past 20 years, I’ve been a public bus driver in Ottawa. I’ve seen a lot of change during that time: new highrises in the downtown core, big-box stores dotting the suburbs, rail transit emerging above and below ground. To me, though, the biggest change has been the rise of sports betting ads. Ever since the federal government legalized single-game sports betting in 2021, flashy advertisements for gambling sites have popped up everywhere. On billboards towering over roadways. On posters plastered to the sides of buildings. On the backs of other buses. On sports radio. During my shifts, I hear teens and twentysomethings discuss their bets as they board the bus.

I’m a recovering gambling addict, abstinent since 2018. Over the past few decades, I’ve played through more than $1 million, betting on games like house poker and virtual blackjack—even gas station scratcher cards. Of that total, more than $600,000 went to sports gambling. I’ve laid down wagers on hockey, football, horse racing, even cricket, even though I don’t know a damn thing about cricket. I did most of it illegally, placing bets with bookies or foreign sports gambling sites.

When I see the new ads around Ottawa, I get angry. I know that recovering addicts like me are going to struggle with temptation. I’ve experienced first-hand how sports betting can ruin a life. I’ve lied to family members, compromised marriages, missed mortgage payments, contemplated suicide, all because of my addiction. I’ve lost a hell of a lot more than money.

***

Growing up, I lived with my parents in Lower Town, just outside of Ottawa’s downtown core. My mother handled most of the parenting while working full time for the government. My father was the sales director at a big printing company. I idolized him. He lived like a rock star, staying out late, treating his clients to dinners at Al’s Steakhouse or the Keg, driving fancy cars, walking around in tailored Harry Rosen suits. People were drawn to him.

During those dinners at the Keg, the wine was always flowing. Everyone ordered three courses, starters, appetizers, desserts, racking up a bill of at least $1,000. My father always picked up the cheque, typically for up to 10 people. He never flinched when it came time to pay. He also had a 28-foot Chris-Craft boat that he docked in Westport, a village on the banks of Upper Rideau Lake. The boat slept eight people and had its own kitchen and bathroom. On weekends, my father hosted big parties on the lake, tying six boats together. They were filled with friends, family and work associates. He always stopped at the LCBO first to stock up on booze for everyone.

My dad’s swaggering lifestyle came at a cost for our family. He was always away on work trips. He regularly had affairs. How do I know? Well, starting from when I was eight, he brought me along. At least a couple of times a year, we hopped in the car and visited his girlfriends around the city. When we arrived, he would turn to me and say, “Noah, go downstairs and play with her kids, distract them.” So that’s what I did. On the drive home, he told me to keep everything to myself. “Make sure you never tell Mom; otherwise we’ll have to split up. Tell her we went to the movies.”

By 2018, I owed $49,000 to my bookie and $26,000 on credit cards. We had to refinance our house to cover the debt.

I kept his secrets. In exchange, he rewarded me with money and gifts. It was an unwritten contract: if my mother never found out, I got pretty much whatever I wanted. Among my friends, I was considered the spoiled one. I always had the latest and greatest toys, goalie equipment and video game consoles. I usually received $20 a day for lunch, a lot for a kid in the ’70s and ’80s. The meal only cost $5, leaving me with a tidy surplus. I liked walking around with a wad of cash in my pocket. Young men can learn a lot from their fathers. Unfortunately, I got an education in selfish, deceptive behaviour.

As a little kid, I was obsessed with sports. I played road hockey into the wee hours of the night with my friends. I watched Sportsline and The George Michael Sports Machine obsessively. I rooted for the Chicago Blackhawks in hockey and the Minnesota Vikings in football. My love of sports was a gateway to sports betting. And I caught that bug early. Like, really early: by Grade 3, in 1984, I was running fantasy hockey pools for my classmates, setting up a draft, creating brackets and tracking statistics. For a $10 buy-in, everyone picked a handful of NHL players and earned points based on their performance throughout the season. The winner took home the pot at the end of the year. Remember, this was the pre-internet era, before up-to-the-second phone updates were the norm. So I regularly woke up early to get the newspaper and look at the scores from the night before. Sports gambling gave me a social advantage, a way to create relationships, a consistent topic to discuss with friends. I even bet on the lunchtime schoolyard football games.

The same year, my parents divorced and my father moved out. He married a younger woman and bought a house across town. I did the back-and-forth thing for a little while, spending every second weekend at my father’s place, but as I got older, the arrangement changed. I saw him less and less. Eventually, I was only going over to his place for an occasional dinner. In 1989, when I was 15, my dad left again—this time for Costa Rica. He planned to retire down there. I knew he would never live in Ottawa again.

I attended St. Matthew High School in Orléans, a suburb just east of the city. By then, I lived nearby with my mother and her new partner. I skipped class most of the time. In the mornings, I forged my mother’s signature during home room and signed out for the day. Then I took the 10-minute bus ride to Place d’Orléans, a shopping mall that had an OLG lottery kiosk where I could buy Pro-Line tickets. At the time, there were only two legal forms of sports betting in Canada: horse racing and Pro-Line. Most people are familiar with the former. Pro-Line, however, is more complex. It’s parlay-style gambling, which involves accurately predicting the outcome of anywhere from three to 10 sporting events. I grabbed tickets off the counter and ticked off my picks. All of it happened on paper. For example, I might bet on the Leafs to beat the Flames in hockey, the Bills to beat the Giants in football and the Blue Jays to beat the Mariners in baseball. The more games I picked, the higher the payout. And I only won if all my predictions were correct.

I spent anywhere from $50 to $150 a day on Pro-Line tickets, using my daily allowance or money I made running the salad bar at the Keg, which paid $13 an hour and up to $300 in tips on a good night. It left me with more than enough cash to support my burgeoning habit. I don’t think my mom ever suspected anything—at least not until later in life. There wasn’t a day that went by where I didn’t place at least one bet. The legal gambling age was 18, but back then, the tellers never asked for ID. If I was lucky, I won once every few weeks. One time, I put down $100 and accurately picked the outcome of all 10 games, which resulted in an $11,000 payout. I was never smart enough to save the money from my wins, though. I usually dumped it right back into more bets.

Whenever I bought Pro-Line tickets at Place d’Orléans, I’d walk five minutes to the Broken Cue, a pool hall and arcade. That’s where I hung out for the day. I never cared about school because I was always finding a way to make money, working odd jobs or placing bets—and I figured I would eventually get rich gambling. I was arrogant. I had friends do homework and take tests for me. The Broken Cue was a big, brightly lit place with at least 15 pool tables and 30-odd video game machines. I liked to play pool against the regulars, but I was lousy at the game and I usually lost. Otherwise, I hung out at the counter, poring over the newspaper, looking at the betting odds. I placed wagers with a big Lebanese bookie named George, who took action on major sporting events like the Super Bowl.

I loved the waiting that came with gambling: those final, dramatic moments of uncertainty, when a last-minute field goal or three-point shot could alter the result of the game. The feeling of anticipation— that’s where I got the high. And when I had several bets going on at once, it felt like my brain was on fire, the ultimate stimulation. Nothing else mattered in those moments. Even if I lost, I never let on that I cared. That was part of the appeal, too. People never knew if I had $100 or $10,000 in the bank. I felt like I was bulletproof, like no matter how it turned out, everything would be all right.

In 1993, I graduated from St. Matthew—just barely, after wasting a couple of years in the Broken Cue. I was 19 at the time, a year and a half older than my peers. Right away, I married my high school sweetheart. By 1996, I was working two minimum-wage jobs. In the mornings, from 2:30 a.m. to 7:30 a.m., I loaded trucks for UPS. Then, during the day, I worked in shipping and receiving for Addition Elle, a women’s clothing store. My wife and I were living in an apartment in the suburbs, and I needed both jobs to pay for our expenses and my habit.

I gambled whenever I could, spending a couple hundred bucks a day. I played poker with my buddies, plugged away at Pro-Line and bought lottery tickets just to look at numbers. I was stuck in married life at a relatively young age, and gambling made me feel alive with possibility. Things quickly spiralled out of control. This was near the beginning of Money Mart, the chain of cash-advance spots that allow customers to borrow up to 60 per cent against their next paycheques. I would bring my pay stubs from UPS and Addition Elle, usually totalling about $6,000 with overtime, to several Money Mart locations, taking out as much as I could. But the interest was roughly 40 per cent. Eventually, I owed $60,000. I’d maxed out credit cards and a line of credit. In 1999, I had to file for bankruptcy.

My wife and I decided to divorce the following year. We realized we weren’t a good fit, and I wasn’t ready to accept responsibility for my actions. I stayed in denial, happily blaming my ex if anyone asked why the marriage ended. It took me a couple of years to pay off my debt to creditors after that.

In 2002, I started driving a bus for the Ottawa-Carleton Regional Transit Commission. By then, I had a new girlfriend, and we’d recently had a child. For a little while, we all lived in a three-bedroom apartment, paying $1,250 a month, but eventually, we wanted a bigger house. In 2003, I went down to Costa Rica and borrowed around $70,000 from my father, no strings attached. With $40,000 of that loan, I made a down payment on a four-bedroom semi-detached in the Ottawa suburb of Beacon Hill. The rest went toward gambling.

At the time, poker was surging in popularity. A boom in online poker sites helped fuel that craze, as did ESPN, which aired the World Series of Poker, showcasing the game for a mainstream audience, turning players into celebrities. I started playing a lot. I had a mortgage to pay off. I convinced myself that if I could get good at poker, I could help my family get ahead. Sometimes, I won big. There were weekends when I entered PokerStars tournaments, winning $80,000 on a $50 buy-in. Hundreds of thousands of dollars flowed in and out of my virtual accounts in those years, but I never cashed out. I just kept betting more.

***

By the time I was 35, I had spent roughly $20,000 a year on gambling, starting from the age of 10—I had lost more than $500,000, including the money I’d made from my wins. I was still gambling late into the night, playing at underground poker halls around town, sometimes coming home as late as sunrise the next day. I was about $35,000 in debt and was forced to ask my mom to help me pay it off. Gambling was affecting my work. It was affecting my relationship. I wasn’t there for my son. Before long, I started missing mortgage payments. One day, my secret was out: the mortgage company contacted my girlfriend, letting her know we’d missed three payments. She was furious, wondering where all the money had gone. How could I have let things get so far out of control?

We split up in 2005. Our relationship had been rocky over the years, and it hit a breaking point when she found out about the gambling debt. I had become the only thing I didn’t want to become—a bad partner, an absentee partner, just like my father. That’s when I realized I needed help. I finally acknowledged that my gambling had ended the relationship and created severe financial issues. So I agreed to attend Gamblers Anonymous. I wanted to show both my ex and my mom that I was willing to get help. The program was once a week—a couple of hours of individual therapy combined with an hour of group.

I went cold turkey, and I hated it. I didn’t really want to stop gambling. Every time I walked past a lottery machine, I thought to myself, Maybe this time I can win millions and solve all my problems. That’s the thing about gambling. With other addictions, like alcohol and tobacco, using only causes harm. But gambling always presents an opportunity to reverse course, save yourself, get out of the hole.

I didn’t gamble for a year. It was the first time I had practised any sort of abstinence. My debts were all settled. And in December of 2006, while on vacation with my buddies in Cuba, I met Julie, the woman who would become my second wife. I told her everything about my past. It was a huge relief to not hide anything. Julie and I got married in April of 2008 and had our first child later that year.

I stayed clean for the next three years, but I struggled. I didn’t spend enough time with my son from my previous relationship. Then things went downhill. In 2010, my ex-girlfriend wanted to change the custody arrangement. Up until that point, we were doing a week on, a week off, splitting things 50-50. But my son wanted to live full time with his mother because I wasn’t giving him enough attention.

One day, before work, I was at the station, waiting for my bus to arrive, when I got a message from an old buddy in the gambling world. He had just started a sports gambling website in the U.K. and wanted me to test it out. The online betting industry was worth some $15 billion by this point, with sites based all over the world, like PartyGaming in Gibraltar, Sportsbet in Australia and Betandwin in Austria.

MORE: Ontario’s online betting boom makes it hard to be a recovered gambling addict

The account came loaded with a $2,500 credit. I figured I was playing with house money—sort of. I only had to pay anything back if my losses took me below $2,500, which seemed like a good deal. But within two hours of getting the text, I had already bet the entire $2,500 credit, with 10 bets going on at the same time. As I waited on the outcomes, neurons firing in my brain, I momentarily forgot about the pain in my life. It was a fantastic, familiar feeling. By the next day, I had negative $500 in the account. I’d lost everything and then some.

That was my first taste of virtual sports betting, and I was hooked. With a virtual bankroll, it seemed like the money didn’t even exist. It was just a number on a website. I didn’t have to go to a bank to deposit cash. I didn’t need to take out loans. I could just link up my credit card and pay for bets. Most importantly, I could hide everything from Julie, who works in banking and would be able to track any other gambling activity. Just like that, I blew three and a half years of abstinence.

My deceptive behaviour started up again. I siphoned off a percentage of my paycheque into a separate bank account, which I used to apply for credit cards and lines of credit. I went to a payday loan place, taking out as much as they would give me, which ended up being $600. Instead of putting that toward paying off my debt, I tried to double it, making bets to try to break even.

I managed to hide my gambling for another three years. All that time, I was under phenomenal stress. Everything became darker. My brain was always preoccupied, never present in the moment. I was always trying to figure out the next bet. People would talk to me, but I was never engaged in the conversation. I missed my kids growing up around me, which was heartbreaking.

In those years, I went on a few road trips to the States to see football games with a friend. Once, near Boston, during a game between the New England Patriots and Houston Texans, I bet $750 on Aaron Hernandez, one of the Patriots players, to score the first touchdown of the game. He did, running into the endzone about 40 feet from where we were sitting. The payout—more than $10,000—was one of the biggest rushes of my life. I got swept up in the moment, celebrating the windfall among the frenzied Patriots fans. But the losses outweighed the wins, of course. My debt had slowly been building, and I was in the pit for $17,500.

At that point, all I wanted was to break even, so in 2012 I put down a wager for US$17,500 on Super Bowl XLVII, between the Baltimore Ravens and the San Francisco 49ers. I figured I would stop after that. Well, I lost, sinking deeper into the hole for a total of US$35,000. I tried to keep it a secret from Julie, but she figured it out. On far too many family outings, I would be looking down at my phone, distracted, checking bets. The fact that everything was online made the problem worse. I could look down at my phone and disappear into another world.

When Julie caught on, I agreed to go to Rideauwood, an outpatient addiction treatment centre in Ottawa.We made a deal: she would get control of all our money, with full transparency, and I would go to Gamblers Anonymous once a week. I also saw a therapist. At Rideauwood, I met Jane, the head of the gambling program. She had blondish-white hair and a soft-spokenness that put everyone at ease. She was my saviour. She thought I had a “provider complex,” that I felt like I had to drive a nice car, have a big house, live a fancy lifestyle, much like my father. Apparently, I also had “champagne taste on a beer budget.” I just kept pissing that budget away, trying to make myself forget how shitty I was feeling, about my father leaving, about my relationships, about my addiction. We made some progress, and Jane suggested that I also check into Problem Gambling Services, an in-

patient program in Windsor. I brushed her off. I thought I would be fine on my own.

***

By 2017, Julie and I had three kids. I had built up some trust. She let me have a credit card again. Things were slowly going back to normal. That July, I received a panicked call in the middle of the night from one of my father’s many girlfriends. She said my father was in critical condition at a hospital in Puntarenas, Costa Rica, about a three-hour drive up the coast from where he lived in Manuel Antonio. He had a perforated bowel. The next morning, I flew down and went to see him in the hospital. We’d never had a great relationship and had barely even spoken in the last six years. And from what I could tell, he was going to die. He told me that I needed to take care of his house and a couple of rental properties in and around Manuel Antonio. Collect rent, get rid of squatters, stuff like that.

Every day, I saw my father during visiting hours at the hospital, from 11 a.m. to 1 p.m., then, in the afternoons, drove back to his properties in Manuel Antonio. During the drive back and forth, I stopped in Jaco, a little Atlantic City–style resort town with casinos and hotels. Overcome with grief and anger at my father’s situation, I started gambling again, playing poker at one of the hotels with a buy-in of $300. I blew $5,000 like it was nothing. After a few days, my father was discharged, and we took him back to his place. Within five hours of leaving the hospital, he died in my arms, just a couple of weeks before his 70th birthday. We held a memorial for him down there.

When I came back to Ottawa, I struggled with the mourning process. I had a lot of resentment toward my father, and once again, I felt like he’d left me. When he died, I lost any hope of resolving our issues. I started drinking more, going to the bar near my house a couple of nights a week. Before long, I entered the bar’s football pool, which I won a couple of times, earning a couple hundred bucks a pop. Not much, but it was enough to draw me back in.

Sports betting is more accessible than ever, seamlessly connected to phones and credit cards. Gamblers can lose their life savings without even getting out of bed.

One of the bartenders introduced me to a bookie. When my inheritance started trickling in from my father’s estate, about $90,000 in total, I used some of it to gamble. I also asked my mother for about $25,000, telling her I needed it to cover my kid’s hockey fees, replace a car tire. I kept these things a secret from Julie. I always told the bookie not to let me get deeper than $1,500.

Of course, I was being naive. Bookies, casinos and gambling sites never tell bettors to stop. Instead, they prey on the vulnerable, their most reliable clients. I knew that if I continued gambling, I would lose my family, my house, everything. I contemplated suicide, thinking it was the only way to stop my gambling and that the life-insurance payout would support my family down the line. But I couldn’t cause so much trouble for them. Julie noticed a change in my behaviour. I was going to the bar three, four times a week. I was angry. I had no patience with my kids, lost interest in stuff I would usually enjoy, like playing men’s league hockey.

That’s when I made a big mistake—or maybe it was a cry for help. One day, in 2018, I was texting Julie and my bookie at the same time, dealing with multiple chats, when I accidentally texted Julie a list of my bets for that day. She wrote back angrily, asking what was happening. At first, I got defensive and proclaimed my innocence. But I knew the jig was up when she asked to come to my therapist appointment shortly after. I decided to come clean.

At that point, I owed $49,000 to the bookie, $26,000 on credit cards. Julie settled up with the bookie and told him never to contact me again. The whole thing put a big strain on our finances—we had to refinance our house to cover the debts—and I had to borrow money from my mom. In September of 2018, I finally admitted myself to the three-week in-patient gambling treatment program in Windsor that Jane had suggested, which thankfully was covered by OHIP. When I arrived, they put all my clothing into a dryer to make sure I didn’t bring in any contraband or electronics. There was no access to the outside world—no phones, no TVs. We had to be at the table when meals were served, promptly at 7 a.m., 11:45 a.m. and 6:45 p.m.

During my time there, I had one-on-ones with therapists and group sessions. The program saved me. It forced me to take a three-week break from my life: no bills, no bookies, no nothing, just dealing with myself. The staff there taught us that it takes time to break a habit, to rewire the neural pathways that control our behaviour. We learned about dopamine spikes and subconscious triggers, including big swings of emotion. I came to realize that when I had thoughts of abandonment related to my father, I used gambling to distract from those feelings. Armed with a better understanding of the addiction, and deprived of access to cash, bookies and sports betting sites, it was relatively easy to get control of my habit.

***

I haven’t gambled since August of 2018. I won’t flip a coin, play rock-paper-scissors. If there’s a 50-50 draw at work, I politely decline to participate. When I feel an urge to gamble, I text Julie to let her know I’m thinking of her. It helps keep me accountable. But it’s getting harder and harder, especially with so many enticing advertisements. One campaign for BetMGM features hockey greats like Connor McDavid and Wayne Gretzky. The ads target broad swaths of hockey fans, making betting seem cool, fun, heroic. Everyone is a winner. The truth is that these places only exist because the gamblers aren’t winning. The money is flowing in one direction.

Before 2021, when Pro-Line and horse racing were the only two legal forms of sports betting in Canada, placing single-game bets was a bit more difficult. I had to either find a bookie and pay them off in cash or register with a foreign sports betting site. At the time, Canadians were spending $14 billion annually on illegal gambling operations and offshore betting websites, playing through sportsbooks.

The Canadian government wanted a piece of the action. So, in 2021, it passed Bill C-218, removing the ban on single-game sports betting, allowing provinces to create their own regulatory authorities. Ontario didn’t waste any time. The province set up a regulatory authority, iGaming Ontario, to oversee the burgeoning industry. By the spring of 2022, there were dozens of sportsbooks registered in the province—big-name international players like Bet365, PointsBet and DraftKings, along with new Ontario-based companies like theScore Bet and BetRivers.

Business was decent at the start. Naturally, professional sports franchises and broadcasters leapt into bed with betting companies. Maple Leaf Sports and Entertainment, which owns the Maple Leafs and Raptors, inked a multi-year deal with PointsBet Canada. And TSN, one of Canada’s biggest sports broadcasters, partnered with the U.S.-based FanDuel. From that point forward, it was virtually impossible to watch a sporting event in Ontario without being inundated by sports betting propaganda. The industry produced $162 million in revenues in Ontario in its first three months of operation.

It could get much bigger. Alberta, which has been fairly cautious in its approach to sports betting, announced that it will allow two companies to enter the industry. Deloitte Canada estimates that the market resulting from single-event sports betting in Canada could grow close to $28 billion within five years. A lot of gamblers will be able to stay within their limits. But what about the people like me, who struggle with gambling addiction? In Canada, more than 300,000 people are at severe or moderate risk of gambling-related problems, according to a recent study by Statistics Canada.

In the digital age, sports betting is more accessible than ever. It’s in the palm of your hand, seamlessly connected to your phone and credit cards. Gamblers can bet—and lose—their life savings without even getting out of bed. Canadians need to be aware of the consequences. I would like to see more contrast advertising, like the kind that exists for the alcohol and tobacco industries. Cigarette cartons are covered in disturbing images of people with cancer. MADD had those macabre commercials dramatizing the results of drinking and driving. The sports betting industry needs something similar—in particular, showing how compulsive gambling can lead to suicide: problem gamblers are more likely to attempt suicide than people with other addictions, at a rate of one in five.

In the U.K., they’re already trying to curtail sports betting advertising. A recent Public Health England study estimated that more than 409 suicides a year in England were associated with problem gambling. The nation’s biggest gambling companies have also agreed to ban betting commercials during sporting events. Ads featuring athletes are prohibited. Other countries, like Spain and Italy, have banned nearly all gambling ads. Canada should follow the leads of our friends across the Atlantic—before it’s too late.

I have four kids in total. My oldest, who’s 21, recently started helping me coach my daughter’s basketball team. The rest of my kids, from my second marriage, are 14, 12 and 10. We live in a nice house in Orléans, with a pool and a hot tub, not far from my mother’s place. I’m the goalie coach and statistician for my 14-year-old son’s hockey team. My relationship with Julie is great. Last year, we spent two weeks in Italy, something I could never have imagined doing while I was in the throes of my addiction, with my finances and focus channelled elsewhere.

Recently, my 14-year-old son asked whether he could place a $5 bet on the Super Bowl, in a pool with his friends from school. I thought about it for a moment. Then I said yes. I told him if it ever got to the point where he couldn’t stop, he could always come talk to me. I want to keep our communication open. I guess, in that way, I’m nothing like my father.

Buy the latest issue of Maclean’s magazine for $9.99 or better yet, subscribe to the monthly print magazine for just $39.99.