Canadian politics are sexist. What are men going to do about it?

Female politicians are speaking up about the harassment they experience on the regular, but the issue won’t improve until men stop staking their masculinity on power.

From left: Sandra Jansen, Rachel Notley and Michelle Rempel.

Share

This post originally appeared at Chatelaine.

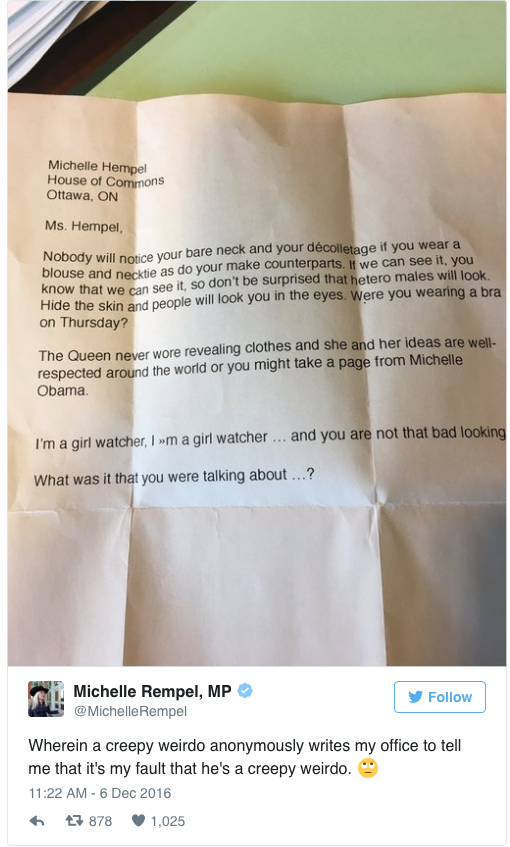

Alberta Environment Minister Shannon Phillips has been called chubby on social media, and her colleague, Health Minister Sarah Hoffman was criticized by a political rival for being “morbidly obese.” Federal MP Michelle Rempel has been called a “bitch” on Twitter (her reply? “that’s Hon. Bitch, P.C. M.P. to you”) and recently received an anonymous letter speculating about whether she wears a bra in the House of Commons.

Cathy Bennett, Newfoundland and Labrador’s finance minister, has been labelled a “monster,” a “witch,” and a “bad person,” who should “do the world a favour” and kill herself. At a protest of Alberta premier Rachel Notley’s implementation of a carbon tax, the crowd shouted “Lock her up!” Notley, a New Democrat with a majority female cabinet, has been targeted with death threats. So has Sandra Jansen, a long-time Progressive Conservative MLA who recently joined Notley’s NDP, citing the growing sexism and intolerance of her own party and its supporters.

It’s been eye-opening to hear the sort of garbage these women deal with every day just for legislating while female. Male politicians receive threats and insults, too, but for women in public office, this kind of harassment, violent and sexually crude in many cases, has become the norm.

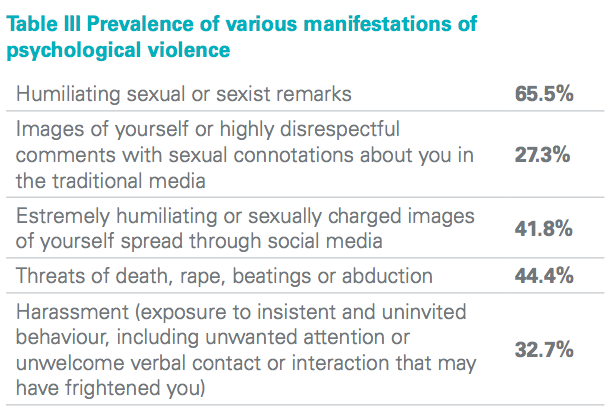

A 2016 survey of 55 female parliamentarians from 39 countries found that 44.4 per cent had received threats of death, rape, beatings or abduction, and 65.5 per cent said they had “often” been subjected to humiliating sexist remarks from male colleagues. And, of course, we all know what happened toHillary.

Good ideas have been floated to address this hostility towards female politicians: last week, the Alberta Council of Women’s Shelters created the Lift Her Up campaign to challenge sexist bullying; and Notley believes we should be encouraging more women to enter politics. In the U.S., women are already responding to the 2016 presidential election by pursuing their own runs for office: since November, more than 4,500 of them have signed up for She Should Run, a new organization that trains women for public life.

But a quick and simple solution is unlikely. The threats and harassment are bound to get worse before they get better. And what’s more: This isn’t women’s problem to fix. This one is up to men. Because men—and it is almost entirely men who’ve been targeting female politicians—are reacting to a very real change. As Don Braid wrote in the Calgary Herald, “Alberta has become a kind of social laboratory, unique in North America, to test whether a near-majority of women in a government caucus makes a change in style and substance. The verdict is already in—they do, as shown both by Notley’s conciliatory style and the NDP’s advancement of women and minorities.”

There are some men who find this progress very, very threatening. For them, the advancement of women, people of colour and LGBT people in politics and other arenas feels like a personal attack. It feels like what has been rightfully and unquestionably theirs for so long is now being stolen away.

American author and academic Michael Kimmel calls this “aggrieved entitlement.” In his book, Angry White Men, which came out in 2013 but seems even more relevant now, Kimmel surveys the growing rage among neo-Nazis, gamers, right wing talk radio hosts and men’s rights activists who define their masculinity and manhood in terms of dominance and power and who believe in their “God-given right” to rule the world.

Female politicians from the right, left and middle have been attacked. Those who identify as feminists have been harassed as well as those who don’t. Their haters simply don’t like that these women are smarter, more powerful and more successful than they are. Given the narrow way they define their manhood, it’s emasculating.

To put it in terms those guys will understand, what they really don’t like is that these women have bigger balls than they do. (Because whether or not you agree with the politics of these women, you have to recognize the guts and perseverance and hard work it takes to run for office.)

Men who believe in equality need to champion the idea of women in power and, more significantly, they need to model for other men that they are respectful of and comfortable with female leaders and female bosses. Michael Kimmel suggests we might start to address white male rage by creating a new definition of masculinity doesn’t depend upon male supremacy, but instead embraces egalitarianism and a true meritocracy.

It turns out that inclusion and social equality are good for white guys, too. Men in marriages where the responsibility for domestic chores and financial support are more evenly shared report higher levels of happiness and less depression. And societies that care for the rights and well-being of all their citizens tend to be the ones that provide a social safety net to protect those, including white men, who have lost jobs or feel disempowered.

Over the last several decades, women have redefined their roles, moving into fields that were previously off-limits, like politics. Now it’s up to men—white, straight men in particular—to redefine theirs. What does it mean to be a man when it’s no longer just a man’s world?