Mapped: 10 years of unprecedented change in Canada’s cities

Canada’s cities have seen a decade of huge demographic change, creating challenges for anyone looking to understand how we live, work, and think

Illustration by Lauren Cattermole

Share

Markham, Ont. is growing fast and changing even faster. The city of 310,000, northeast of Toronto, saw its population balloon 15 per cent between 2006 and 2011, according to census figures, and was recently anointed Canada’s most diverse community by Statistics Canada. Nearly three out of every four Markham residents claim “visible minority” status, with more than a third of the population hailing from China. Other sizable groups include South Asians, Arabs, Koreans and Filipinos.

Lori Wells, a community recreation manager for the City of Markham, says local officials knew all this, but struggled to meet residents’ expectations nonetheless. By 2011, registration in many children’s programs—volleyball, basketball, drawing, crafts—was stagnating or on the decline. “The demographics in the community were changing,” Wells says, “but we were doing the same old thing.” In a bid to stay relevant, the city’s department of recreation and culture hired Toronto-based Environics Analytics, a marketing service company. The resulting analysis, which drew on vast databases about Canadians’ incomes, shopping habits, lifestyle preferences and even social values, suggested the city’s traditional panoply of “fun in the sun” recreational programs were an increasingly poor fit for a community more interested in science and technology. So planners created new children’s camps focused on robotics, rocketry and math. Enrolment skyrocketed. Last year, the city even added an “economics” camp for kids aged eight to 12. Campers built lemonade stands and then marketed and sold their thirst-quenching product using play money. “The camp was sold out,” says Wells. “We were shocked.”

Click here to find out which Environics Analytics-designated lifestyle segment is most associated with your neighbourhood

Like Markham, cities across Canada are being reshaped by the country’s changing face, creating challenges for marketers, politicians, community organizers and anyone else trying to understand how people live, work, shop and think. “There are a couple of challenges we hear about a lot [from clients],” says Jan Kestle, the founder and president of Environics Analytics, “and that’s not understanding the diversity within the diversity.”

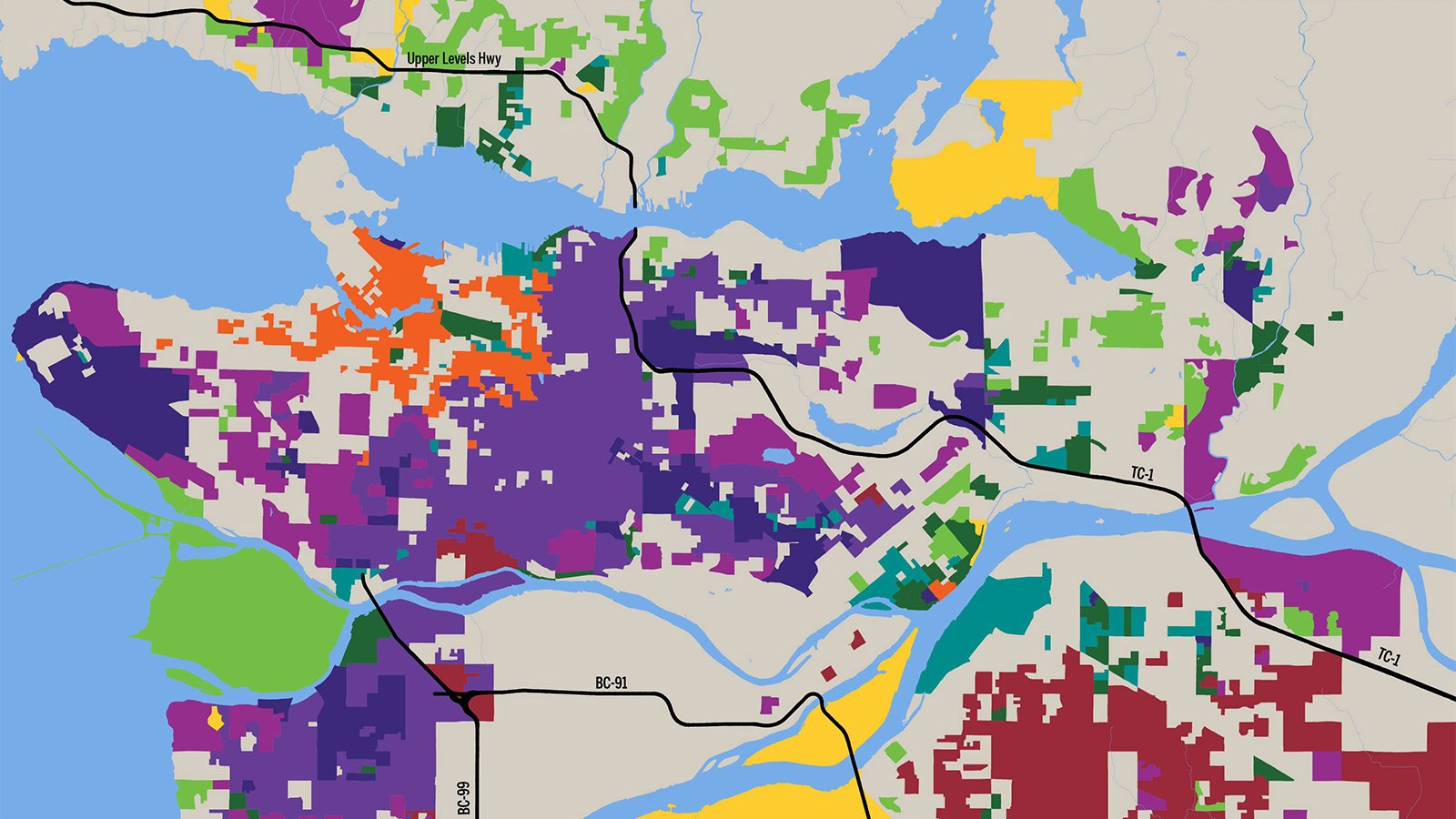

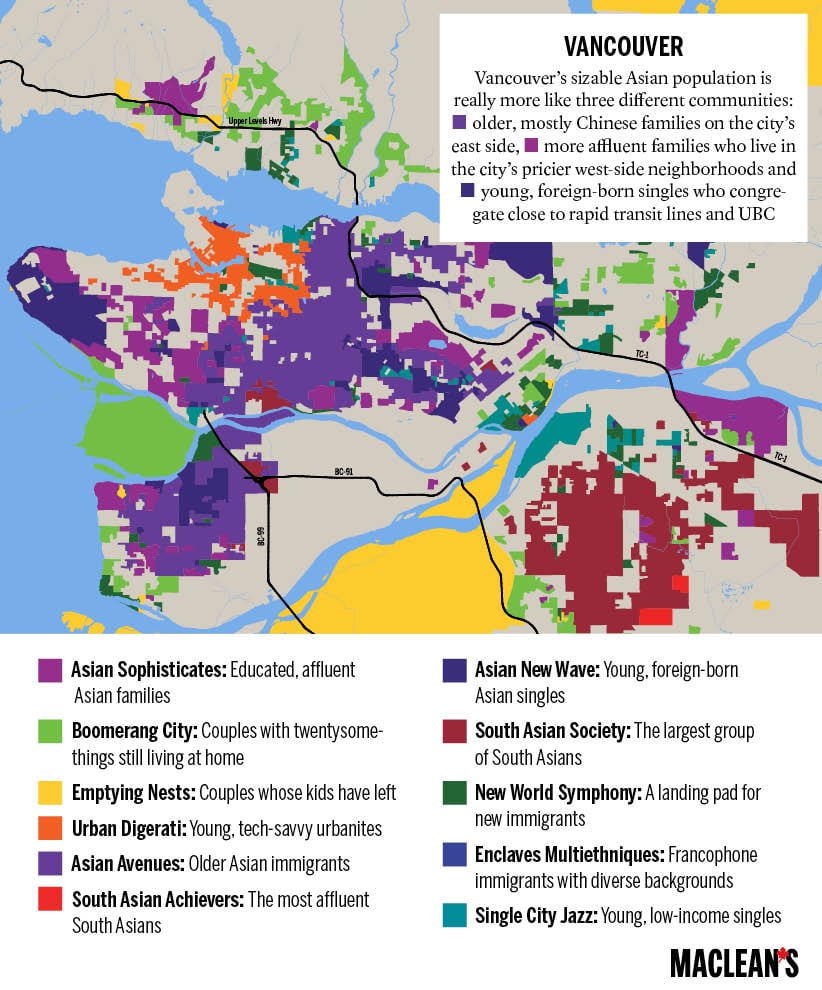

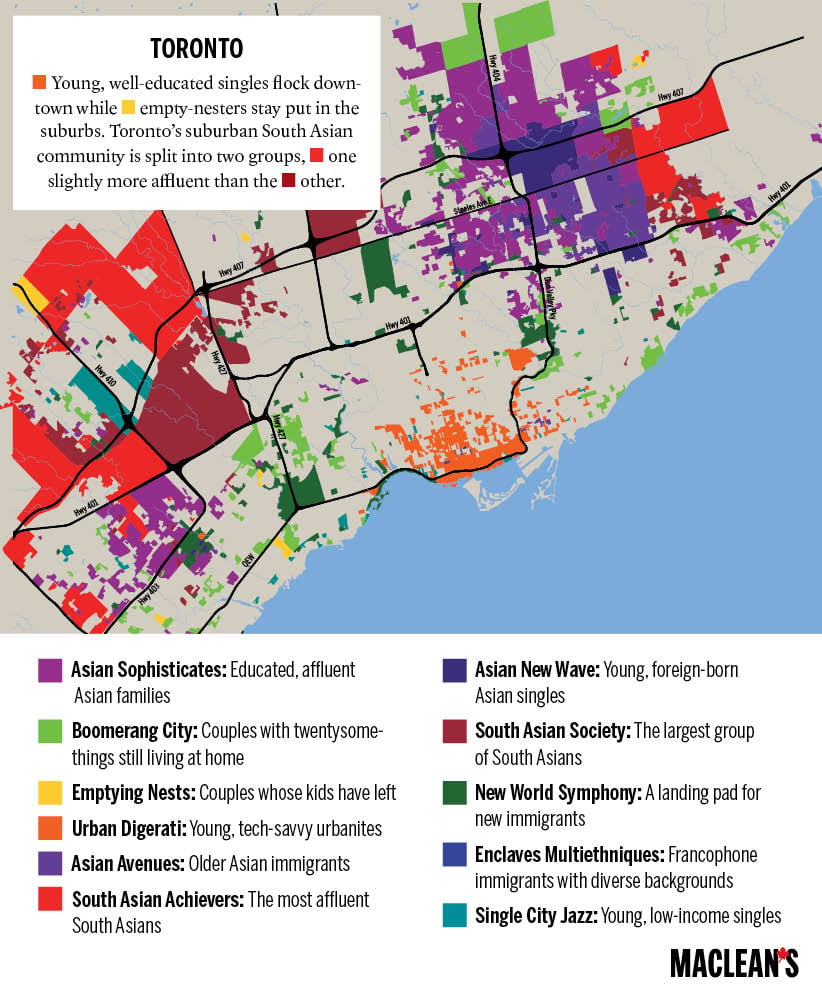

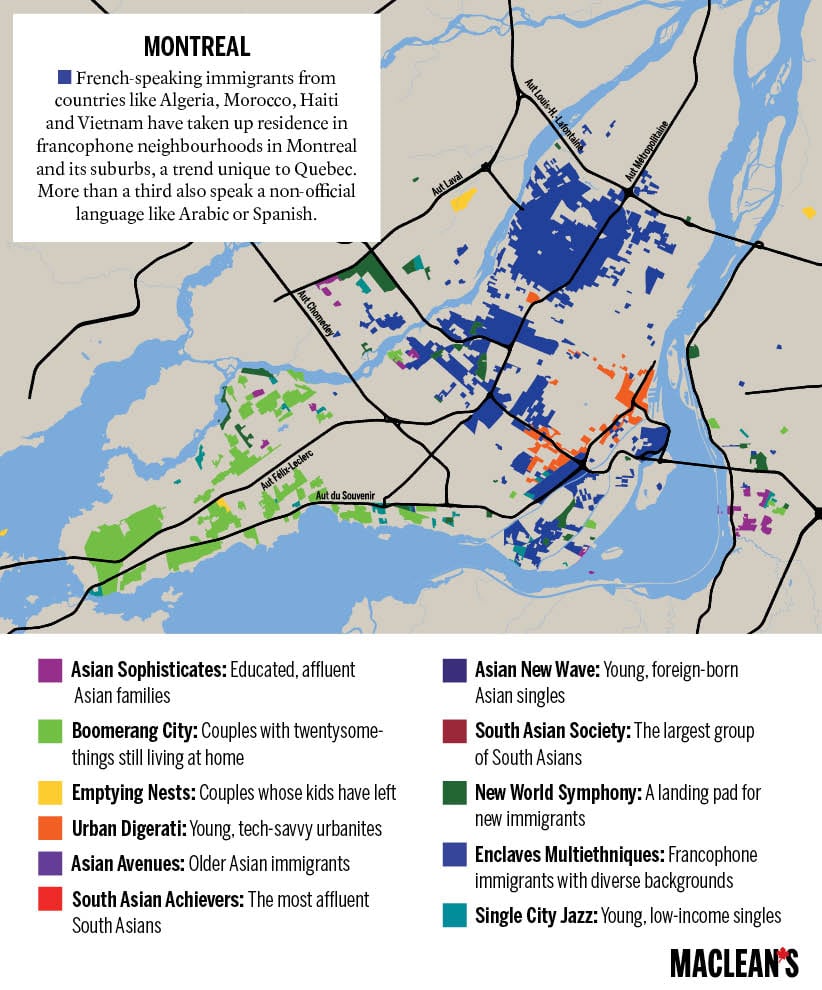

Since 2004, Environics Analytics has tried to offer more insight into Canadian communities by dividing the population into different segments, based on criteria such as age, income and lifestyle choices. But Kestle says unprecedented demographic changes over the past 10 years have forced Environics Analytics to overhaul its model, resulting in changes to nearly three-quarters of the 68 different lifestyle segments it tracks. All that data-crunching has resulted in a fascinating snapshot of Canada in 2015—right down to individual postal codes, with the accompanying maps highlighting 11 lifestyle categories that best show how immigration, urbanization and an aging population are reshaping Canadian society. Each neighbourhood is assigned a segment that most closely fits its makeup, according to Environics.

With names like “South Asian Society” (immigrants who arrived since 1990) and “Single City Jazz” (young, low-income singles and single-parent families), Environics’ segments come with their own particular lifestyles and unnervingly specific collection of traits, including breakfast cereal preferences, faith in the government’s ability to fix problems and whether members surf the web while watching TV. Taken together, they reflect the impact of continued immigration—Statistics Canada said two-thirds of population growth in Canada’s biggest cities last year was due to new arrivals—as well as the growing divisions within ethnic groups. They also show how empty nesters are opting to stay in the family home while their kids abandon the suburbs in pursuit of urban lifestyles (although significant numbers of adult-aged children are also moving back home in the face of a tough job market).

In Vancouver, for example, a group once simply deemed “Asian” by naive marketers has emerged as a far more complex community. Older immigrants from China and, to a lesser degree, the Philippines and Vietnam cluster on the city’s east side and the suburb of Richmond to the south. These are families that boast moderate educations but have nevertheless prospered in their adopted country, the data suggests. They like computers and other technology, shop at Banana Republic and prefer multicultural TV and radio. Contrast that to the more upscale Asian families who can be found on Vancouver’s pricier west side and the city of West Vancouver. With average household incomes in excess of $130,000, they tend to shop at Holt Renfrew and Harry Rosen, travel frequently and drive 2012 or newer model-year vehicles—preferably a Mercedes. Young, well-educated Asian singles comprise a third group: they are new to Canada, very web-savvy and tend to rent apartments along SkyTrain and other major public transit lines.

Similar divisions are now noted in South Asian communities. In Toronto, a more affluent subset, dubbed South Asian Achievers by Environics, tends to live in newly built suburban neighbourhoods to the northwest and northeast of the city. They are relatively recent immigrants with mixed educations who are voracious cellphone users, who enjoy basketball and are eager to learn what it means to be Canadian. By contrast, the second group of South Asian families earn average incomes and live in multi-generational households. They comparison shop, click on Internet ads and like mobile coupons. They are fond of soccer, nightclubs and see themselves more as global citizens. “Very few populations in the history of immigration to Canada have, beyond the first generation of immigrants, utterly retained their homeland’s culture,” says Alan Middleton, a marketing professor at York University’s Schulich School of Business. “It obviously gets blended with what’s here. So to understand that complexity, marketers and researchers have finally decided they can’t just have one, narrow little sub-group called Asian or South Asian. We have to break it down and find out what’s really going on.”

In Montreal, meanwhile, a unique situation is occurring, as French-speaking foreigners from Algeria, Morocco, Haiti and Vietnam are drawn to francophone neighbourhoods, creating a conundrum for marketers who will have to figure out whether to target them with French ads or ones translated into their native tongues. The issue of language can be a thorny one outside of Quebec, too. “People who aren’t experienced in cultural marketing will assume they need to translate everything,” Kestle says. “But many immigrants prefer to be marketed to in English.”

Another split has occurred along strictly generational lines, with the downtowns of cities like Vancouver, Toronto, Montreal and Calgary filling with young, urban singles who live in high-rise condos, drink microbrewed beer and take Pilates classes. Their empty-nest parents, meanwhile, are staying in the suburbs, although a good many are still allowing their children to move back home—several Calgary neighbourhoods show evidence of this “boomerang” activity—as they struggle to get a foot on the property ladder or get started in professional careers. Nearly a third of those multi-generational households include “kids” over the age of 20, Environics’ data suggests, and therefore tend to be interested in youth-centric activities like skiing and snowboarding.

Though it’s difficult to believe such profiles accurately describe a neighbourhood full of near-strangers, experts say the approach is more accurate than many expect. “However different we think we are from our neighbours, in broad categories—general attitudes toward life and consumption patterns—most of us are actually quite similar,” Middleton says. “It’s a very human emotion—we choose not just the property we like, but the area where we feel most comfortable.” Put another way, we are where we live.