The murder trial that took New Brunswick by storm

How Saint John, one of Canada’s most pleasant places, fell into the grips of the Oland family’s trial of money and murder

Dennis Oland, accompanied by his mother Constance Oland, arrives for the start of his trial in Saint John, N.B. on Wednesday, Sept. 16, 2015. Oland is charged with second degree murder in the death of his father. Richard Oland, 69, was found dead in his Saint John office on July 7, 2011. (Andrew Vaughan/CP)

Share

Update: On Oct. 24, 2016, an appeal court overturned the guilty sentence handed to Dennis Oland, giving him a new trial.

Clad in red, Judith Meinert slipped into the courthouse elevator with a man accused of murder and his team of defence lawyers: “Good morning, everybody!” Offering high-fives and arm squeezes all around, she joined her friends in the courtroom and claimed her front-pew seat to watch the proceeding, which she did nearly every weekday during the September-to-December trial. When another woman began handing out candy canes, Meinert enforced the courtroom rules: “No gum, no treats, no candy, no nothin’.” Their preliminary prattle spanned complaints about the price of Lego to boasts about 29 deer spotted on someone’s front lawn, until the sheriff and judge entered the room. “Here they come, here they come,” the audience whispered.

Meinert, a 75-year-old retired schoolteacher, listened with ears perked to the arguments for and against Dennis Oland, a 47-year-old man who was charged with bludgeoning his millionaire father, Richard, to death in July 2011. The trial was one of the longest and most expensive in the history of Saint John, N.B., a port city of 140,000 people who usually share a remarkably rainproof good nature.

While Meinert and her fellow observers didn’t know Dennis personally, the case intrigued them because of the rare ghastliness of the murder—Richard’s secretary had found him in a puddle of blood, with 45 wounds from a hammer-like weapon—and also because the Oland family, which founded and operates Moosehead Brewery and other local companies, is a fixture of Saint John.

Dennis was the last person seen with Richard at his office the evening of the death, and was suspected to have lashed out at his father for hoarding a fortune, betraying Dennis’s mother, Connie, by keeping a mistress, and for mistreating Dennis as a child. “It’s like an opera,” said Meinert. “There’s blood, sex, money, everything.”

In the hours before the attack, Dennis had seemed flustered. Camera footage showed he went to and from his father’s office three times that evening, and crossed and re-crossed the one-way street out front before driving up it the wrong way. The Crown had binders full of witnesses to testify they had seen Dennis at a wharf that afternoon, where Dennis said he had picked up beer bottles but didn’t remember what he did with them. He had been carrying a cloth bag—Dennis said that people called it his “man purse”—the same one he had later brought to his father’s office. Clues pointing to the motivation for murder showed that, after losing money through divorce and chronic overspending, Dennis had taken a collateral mortgage, asked for early paycheques from his job at CIBC and borrowed $538,000 from his father. After Richard’s death, Dennis’s debt to his father was erased. He also inherited $150,000 (Richard had left most of his money in a fund for Connie), and became co-director of two of his father’s companies and president of one. Police found three drops of Richard’s blood on the sports jacket Dennis had worn that evening, which he had had dry cleaned the next day.

But Alan Gold, one of the four well-known defence lawyers, pointed to the disturbing mystery of the case: the spots of blood could have been months or years old at the time of Richard’s death, and were so subtle that the dry cleaner hadn’t noticed them. With the crime scene crusted with 360-degree blood spatter, how could Dennis’s jacket and other clothes have stayed so clean? Police had found no evidence of someone washing off blood in the office bathroom, so why was there no blood in Dennis’s car or on his “man purse?” A scuba-diving search around the wharf and multiple searches of Dennis’s house had revealed no murder weapon. And how could Dennis have pummelled his father around the time he had been seen in a store buying milk and at home rounding up his free-range hens? Gold spoke to the jury for 3½ hours in his closing arguments, spoon-feeding them reasonable doubt.

“He really hammered it home,” Meinert whispered to her neighbour. “Whoops, bad choice of words.” Patty Dow, 58, helped Meinert annotate the proceedings. “The prosecution should show more expression,” she said. “I’d like to see him just a little more punchy.” Despite the strength of the defence, Meinert and Dow believed Dennis was guilty, while about half the community belonged to the other school of thought.

The women were still captivated toward the end of the eight-hour day, as Justice John Walsh explained the forensic concept of “capillary electrophoresis” and the jury members, like lifeguards, had to work to stay alert. As Walsh gave them a recess and encouraged them to “keep on truckin’,” Dow relaxed into the pew and elbowed her neighbour. “This would be a great time for an ice cold beer.”

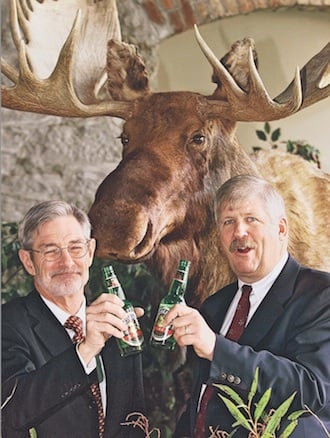

Moosehead Brewery is a focal point of New Brunswick. Set in central Saint John, the factory features a wall of original bricks from its founding by Susannah Oland in 1867, as well as a taxidermic moose to greet guests. Inside, Patrick Oland, Richard’s nephew, wears a reflective vest over his dress shirt and takes a visitor underground to the kegs. While Patrick and his brother, Andrew, run Moosehead, Richard made his $37 million by establishing investment and transport companies, always with the merciless determination of Duddy Kravitz. When one of his former companies, Brookville Transport, declared bankruptcy, he never repaid the money he owed the mechanics. He poached clients from smaller trucking companies and would have put Bud the Spud out of business if he felt like it. He verbally abused his wife and four children, including Dennis, but remained devoted to his beloved sailboat.

Moosehead Brewery is a focal point of New Brunswick. Set in central Saint John, the factory features a wall of original bricks from its founding by Susannah Oland in 1867, as well as a taxidermic moose to greet guests. Inside, Patrick Oland, Richard’s nephew, wears a reflective vest over his dress shirt and takes a visitor underground to the kegs. While Patrick and his brother, Andrew, run Moosehead, Richard made his $37 million by establishing investment and transport companies, always with the merciless determination of Duddy Kravitz. When one of his former companies, Brookville Transport, declared bankruptcy, he never repaid the money he owed the mechanics. He poached clients from smaller trucking companies and would have put Bud the Spud out of business if he felt like it. He verbally abused his wife and four children, including Dennis, but remained devoted to his beloved sailboat.

When Richard donated money, he attached all sorts of strings to it. He helped organize and sponsor the 1985 Canada Games in Saint John, as well as build an entire Catholic church in Rothesay, the town just outside Saint John where the Oland estate is set. But, as Rothesay Mayor William Bishop explained, “he came in about two or three times a year and made sure I knew how the town should be run. He’s one of those people who gets right in your face to make sure you’re listening.”

Because Richard wanted a bird-releasing spectacle at the opening ceremony of the Games, Bishop had to keep a dove in his house for a month beforehand. “It drove me crazy, saying ‘coo, coo, coo.’ ” Elsewhere, Richard was notoriously stingy; he cut off funding to the Rothesay Pony Club, which his father had run at the family estate to teach people to ride horseback. Buskers at the Saint John city market complained that Richard never tipped.

Despite Richard’s reputation, the Olands blended in as ordinary New Brunswickers. Dennis’s kids went to public schools in Rothesay and joined sports clubs, and his father and uncles handed out beer around the yacht clubs, even to men in rowboats. “They seem to be just good, regular people in the community,” said Bishop. “I think you find that with Maritime families—the Irvings, the McCains, the Olands—they don’t try to dominate or take over. They play their role and they fit in. It seems embedded in us.” Richard went to Christmas parties at a local inn, which was “no big show,” said Bishop. “He was just an ordinary citizen.”

The family seemed equally ordinary among people in Saint John—a place where restaurant customers are inclined to offer a bite of dessert to the waitress, and drivers with high-speed windshield wipers will stop at a green light if the pedestrian waiting to cross looks cold enough. “The Olands don’t act like hoity-toity, uppity people,” said Dow. “They weren’t the royals,” echoed Barbara Pearson, whose daughter learned to ride at the Rothesay Pony Club. (In fact, the evening of the murder, Dennis said he was discussing genealogy with his father and discovered that their Oland ancestors were not aristocrats.) Indeed, this modesty isn’t new. Four generations of Olands are buried in a Rothesay cemetery across the street from a Dairy Queen, their gravestones as small as Halloween decorations. Even Gold, their lawyer from Toronto, who admits he is a “come-from-away-er,” acknowledged the culture. “While I’m not from here,” Gold told the jury in his closing arguments, “I’ve come to admire your way of life.”

The trial sentenced the Olands to celebrity. For the 4½ years since Richard was found dead, rumours slow-cooked into theories involving a Russian mafia hitman and a psychopathic plan to “knock off Connie next.” The interest spanned age groups. “Some of my friends have different theories,” said Ben Morris, 15. In pubs, conversations shifted from comparing the heights of Christmas trees to debates about “circumstantial evidence” and the nature of evil.

Throughout the trial, Mayor Bishop received morning updates from a friend who drove to Saint John to watch. “We have coffee in the mornings, so he relays to us what’s going on,” he said. In the city, many people turned to Meinert, who briefed them each evening after court. “One time I had a pizza party with a bunch of nuns,” Meinert recalled. “They heard I was going, and they wanted to know everything. ‘Well what did the mistress say? What did he look like?’ Everything.” (The mistress, Diana Sedlacek, said she was at home with her husband the evening of the murder and had tried to reach Richard by phone).

Evidence raised in court meant the public did, in fact, learn just about everything. Exhibits made public included Dennis’s bank statements, child custody conditions and emails to his second wife with subject lines like “$$$,” along with text messages and selfies Richard sent to Sedlacek and details on his dry scalp condition, which, lawyers argued, could have caused the bloodstains on Dennis’s jacket during an innocent embrace. One of the Olands’ lawyers, William Teed, said the family’s right to privacy had been “run over by a truck.” The most curious observers took drives through Rothesay to scope out the family estate where Dennis’s family lives—its barns, horses and wobbly wooden fences causing their imaginations to flare with thoughts of Murdoch Mysteries. Lanterns glowing on the trees at night and footprints in the snow didn’t help the cause.

Over the course of the trial, many of the Olands retreated. Dennis’s kids were pulled out of school. The estate, where Dennis and his wife live, has a hedge almost as high as the net of the trampoline, as well as a “no trespassing” sign at the front of the laneway. In court, the family always kept to its reserved pews, and they recessed in a corner of the hallway with Timbits and coffee. The crime scene, where Richard’s associates still work, kept its curtains closed all day. Dennis’s wife, Lisa, started running an upscale, quirky consignment shop—with a Burberry blouse on sale for $96 and a chart outlining how to dress for the Kentucky Derby—but an employee inside appeared uncomfortable at a mention of the case.

Perhaps most notably, the family chose not to disclose the location of Richard’s grave. He was not buried in the cemetery plot with his ancestors, even though there’s space.

Beginning on Dec. 15, Walsh took more than a day to instruct the jury. The Crown needed to prove Dennis’s guilt beyond a reasonable doubt, and Walsh reminded the jury of myriad possible doubts, including the weakness of the blood and other DNA evidence on Dennis’s jacket. As Gold put it, “We shed our DNA as we go through life. We cough, we spit, we get nosebleeds, we pick scabs.” And some people in particular are DNA “shedders.” Other questions centred around the lack of evidence concerning a financial or emotional motive; a computer forensic expert hired by the family had found no antagonistic emails or other messages between Dennis and his father, even after mining an electronic history the size of “the Library of Congress 10 times over.”

That the Saint John police were controversially—and almost comically—sloppy sleuths helped to explain the lack of evidence. While working on the crime scene, officers used the bathroom for two days before it could be tested for blood or fingerprints, and they couldn’t always remember what they had touched around the office with bloodied gloves. The blood spatter expert didn’t arrive from Halifax until four days after the murder, by which time the body had been removed and spatter had dried and flaked. Officers touched the back door before testing it for fingerprints, didn’t interview some witnesses for 18 months, and didn’t photograph the back alleyway until three years after the crime.

The Saint John Police Department earned such little respect from Richard’s co-worker, Robert McFadden, that he refused to give a voluntary DNA sample, leading the police to seize a straw from his glass at East Side Mario’s. After a two-year investigation involving multiple house and underwater searches, police found no weapon. The New Brunswick Police Commission is investigating the investigation. As Gold put it, “This isn’t the police’s finest hour. Never has the police looked so long to find so little.”

Despite the darkness of the trial, all parties maintained a Maritime approach. When power cut out in the courthouse, leaving everyone in blackness for the second time during the trial, the judge simply said “Hm . . . ,” and a security guard in the lobby pointed out, “We’re not having much luck with this building.” When the judge had to dismiss one of the jurors before deliberations began (the jury had an extra member throughout the trial in case one got sick or otherwise couldn’t continue), he told them, “This is the part I really didn’t want to come to. I am compelled to express my personal, heartfelt thanks.”

Meinert built a camaraderie with “the regulars” who came to watch, and guards joked about charging them admission. Even when Meinert was absent for a funeral or volunteering gig, her new friends reserved her seat.

After just two days deliberating, the jury was decided. “It’s verdict time,” said Greg Marquis, a historian at the University of New Brunswick who is writing a book about the case. In response to an email alert from the court communications officer, Marquis and reporters flocked to court. Meinert was driving to Halifax to visit her family; Dow was in Moncton, and almost none of the other regulars arrived before the judge entered and the sheriff instructed the courtroom to rise. The audience—mostly Olands—sat back down and stayed rigid, as if posing for the sketch artist.

Guilty. Ninety-four days after the start of the trial, on a Saturday morning at 11:10, the judge announced the verdict. Dennis wept and cried, “Oh, no!” and “Oh, God!”, while Connie curled over in the pew and Dennis’s sister bent over her and cried on her back. Lisa turned to the jurors and said, “How could you do this?” Meinert was in the car, fixed to CBC Radio as her husband drove, when she heard the verdict in a news bulletin. “It’s a good thing I wasn’t driving,” she said. “I probably would’ve put the car off the road. I thought he was going to be found not guilty by reasonable doubt.” Meinert was equally shocked by Dennis’s outburst. “I think it just bushwhacked everybody because he had been so self-contained throughout the trial.”

A sentencing hearing was set for February, and police took Dennis into custody immediately. The maximum sentence for second-degree murder is 25 years without chance of parole, and all 12 jurors recommended giving no chance of parole for at least 10. “We are shocked and saddened,” said Connie in a statement. “Our faith in Dennis’s innocence has never wavered.” Patrick stated the same: “All Oland members are certain Dennis had nothing to do with the death of his father.”

Observers who still think Dennis isn’t guilty note that Richard had many enemies who wanted him dead. “Richard was a bad cat,” said Pearson. Mayor Bishop described the man’s funeral: “I don’t know how to put this . . . the church was packed, but there wasn’t a tear shed. People weren’t disturbed emotionally.”

Although Dennis has been found guilty, most people add the epithet “for now.” Right after the verdict came out, many Saint Johners expected the Olands to appeal and eventually win—largely because they have the money to hire “those highfalutin lawyers.” “I bet they’re making a pretty penny,” said Dow, adding she’s heard rumours that Gold, who defended the Hell’s Angels in 2004, makes $1,000 per hour. Although his rates aren’t public, other lawyers estimate a legal bill of between $2 million and $4 million for the defence alone, including the preliminary trial in December 2014. Gold confirmed that the defence plans to appeal.

Whatever their opinion on the verdict, fellow Saint John residents share sympathy for Dennis. “He’s a poor little pup who never grew up,” said Anne Fletcher, another trial regular. “He’s not my son but I feel for him.” They also feel for the rest of the Olands. Bishop predicted that “there won’t be any animosity toward the family. Connie’s such a nice person. I think once the thing is over, life will go on.”

Meinert described the trial’s finale: “It was a Shakespearian tragedy where everybody loses. The mother, who was so gracious throughout the trial, has lost her son for a while and her husband permanently.”

For Meinert and company, the end of the trial means their lives must also go on. “I can’t believe it. I don’t want to leave everybody,” Meinert said just before deliberations began. “It’s been a pleasure to meet you,” she told her friends. As the judge left the courtroom, Meinert approached each familiar face, no longer giving high fives but rather shoulder pats and hugs. In a city as quaint as Saint John, she will almost surely see them around; although, in case she doesn’t, she is already planning a one-year reunion. “Life as I know it will resume,” she said, “but when it’s time for sentencing I’ll be right back there. We certainly haven’t seen the end of this saga.”