Vancouver’s ‘symbol of disparity’: a $4.8-million chandelier

The city’s latest piece of public art: a vision of opulence in the type of space where homeless people seek shelter

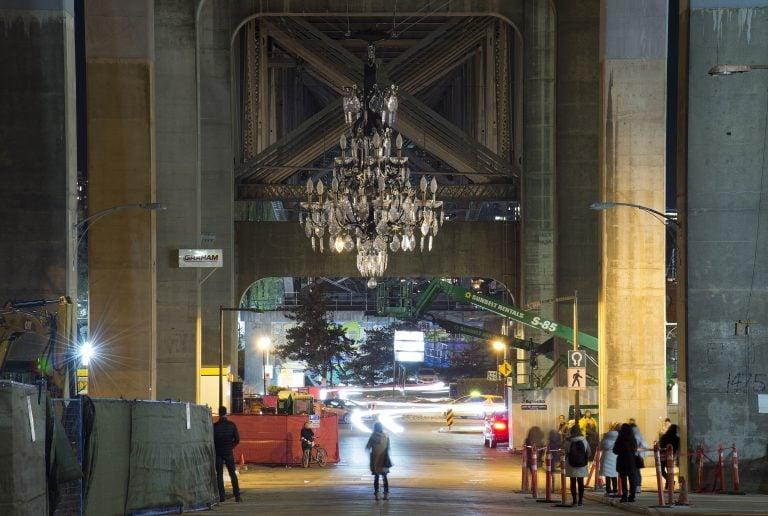

The Spinning Chandelier, an art installation under the Granville Street Bridge in downtown Vancouver, B.C. (Jonathan Hayward/CP)

Share

The 3,400 kg chandelier had been affixed days earlier by a web of thin metal cables to the underside of Vancouver’s Granville St. Bridge, a space that has long been an unwelcoming dead zone. Despite its heft, the translucent sculpture looks ethereal against the towering cement bridge supports. A crowd had gathered, not so much to hear renowned Vancouver conceptual artist Rodney Graham thank Isaac Newton for inspiring the piece he calls Spinning Chandelier, developer Ian Gillespie who bankrolled the $4.8 million sculpture or the many crafts people at the artists’ foundry in Walla Walla, Wash. who constructed it from more than 600 polyurethane crystals and stainless steel. They were waiting for the moment when the chandelier would be illuminated, slowly descend and then spin before rising again to its resting spot with lights off: a cycle it will repeat twice a day.

When the switch was flicked, Spinning Chandelier lit up like the 200-year-old French chandelier upon which it was modelled. There were cheers from the well turned out audience, who looked to be mostly neighbourhood folk living in condominiums, many with views of nearby False Creek.

One woman in a full-length fur coat admired the artwork but wondered how they would control pigeon droppings which are the bane of artists world-wide. Claud Brunelle who has lived in the area for more than 20 years applauded the sculpture which will be the centrepiece of an artsy gathering space—eventually photographs will be projected against the bridge struts—edged by shops and cafes. “We never really had anything down here. Now we are getting a grocery store and a London Drugs. This is going to revitalize the whole area.”

READ MORE: Yachts versus rowers: In Vancouver this is class warfare

Of course, this being Vancouver where the gap between rich and poor is widening, not everyone is as enthusiastic about this or any other move that smacks of gentrification. Backlash against the sculpture erupted before the official unveiling from people, mostly on the political left, who hadn’t yet seen it. In part it was a reaction to the high cost of the sculpture which fulfilled Gillespie’s public art contribution for a luxury tower called Vancouver House adjacent to the bridge. The city requires developers to contribute $1.2 million toward public art for developments over 100,000 square feet, says Erick Fredericksen, Vancouver’s head of public art. In this case, Gillespie was permitted to bundle his art contribution from Vancouver House and three other developments to pay for Graham’s signature piece.

The disapprobation is exacerbated by the location and symbolism of the chandelier—a vision of opulence in the type of space where homeless people seek shelter. When the first photographs of the artwork appeared, Twitter erupted with critiques from Vancouver’s left pointing out the sculpture is only a few kilometres from a downtown park where homeless people have been living in a tent city for more than a year. Among those voices was Carrie Bercic, a city activist and former school trustee. “It really breaks my heart,” she says. “I’m certainly in favour of public art and I’m in no way disparaging the obvious talent of this artist.” But in a city facing an opioid and homelessness crisis, it’s money that could be put to better use, she says. “It looks like a symbol of disparity between the haves and have nots in this city.”

Critics like Bercic are unmoved or perhaps don’t know that in addition to the public art contribution, Gillespie’s company Westbank was required by the city to build 106 units of rental housing and contributed $17 million in community amenity contributions and development cost charges in exchange for rezoning the Vancouver House site. The city can use that money to help pay for social housing, childcare spaces, heritage conservation and cultural facilities, to name a few.

Still, there those in Vancouver who won’t cut Gillespie any slack, regardless of his contributions. A collector of couture gowns who muses poetic about the value of beauty, Gillespie often faces backlash from Vancouverites priced out of the housing market over the past decade. In lefty circles his name is synonymous with the boom in luxury condos, which he unabashedly markets to overseas buyers who in turn are blamed for pushing up property values.

Since 2000, the value of Vancouver real estate has increased by more than 300 per cent. And the benchmark price of a detached home in the city, although lower than it was last year, is still $1.2 million. Although there are plenty of other developers building luxury condos and selling into the same market, Gillespie gets more than his share of the flack probably because he is one of the most successful. He defends his buildings and the art in and around them as beautiful and important cultural additions to the city and blames government inaction, not foreign buyers, for the city’s lack of affordable housing.

Fredericksen points out the city has an art committee that vets public art projects, but the whole process takes a fairly hands-off approach. He says developing the nowhere land under Granville Bridge mirrors an international trend of cities trying to make better use of the unused space under bridges and freeways. New York has been working on uses for space under elevated portion of FDR Drive and Seattle has built dog and skateboard parks beneath an elevated section of the I-5.

There is, he points out, another way to look at the transformative effect the city hopes Spinning Chandelier will have on the space under the Granville Bridge. “It’s a big move to point to this very industrial infrastructural landscape as public realm.” Part of what a chandelier hung under there does, he says, is domesticate the space, albeit in a “really scaled up sort of way.”